Authors: Martin Barrett and Jeffrey R. Farr

Department of Recreation and Parks Management, Frostburg State University, Frostburg, MD, USA

Corresponding Author:

Martin Barrett, PhD

101 Braddock Road

Frostburg, MD 21532-2303

mbarrett@frostburg.edu

301-687-4475

Martin Barrett, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Sport Management at Frostburg State University in Frostburg, MD. His diverse research interests focus on sport and environmental sustainability, the diffusion of non-traditional sports, and divisional reclassification within intercollegiate athletics.

Jeffrey R. Farr, PhD is an Assistant Professor of Recreation, Parks, and Sport Management at Frostburg State University in Frostburg, MD. His research interests focus on understanding the relationships between families and youth sport participation.

Marketing Division II athletics to college students: The perceived effectiveness of internally focused promotion tactics

ABSTRACT

Sport-based incentives such as sales promotions and atmospheric efforts such as augmenting the core product with entertainment programming are widely used in sport to increase attendance at events. Despite this, there is little understanding regarding the effectiveness of marketing and promotion activities in persuading and motivating college students to attend Division II athletic events. Therefore, this paper sought to understand the

perceived effectiveness of different types of marketing and promotion activities, as well as the relationship between perceived effectiveness and existing attendance behavior. Surveys collected from students attending a public university in the Mid-Atlantic region (N=327) revealed that behavioral response incentives – marketing tactics where the sport product is augmented to better match the primary motive for fan attendance – have the greatest perceived effectiveness in persuading and motivating attendance. In addition, behavioral response incentives were positively related to attendance behavior; meaning students who were already regularly attendees perceived these types of marketing and promotion activities to be even more effective. The results from this study should guide athletic marketing efforts at the Division II level in the implementation of marketing and promotion activities to generate optimal return on investment.

Key Words: athletics, marketing, promotion, incentives, atmospherics

INTRODUCTION

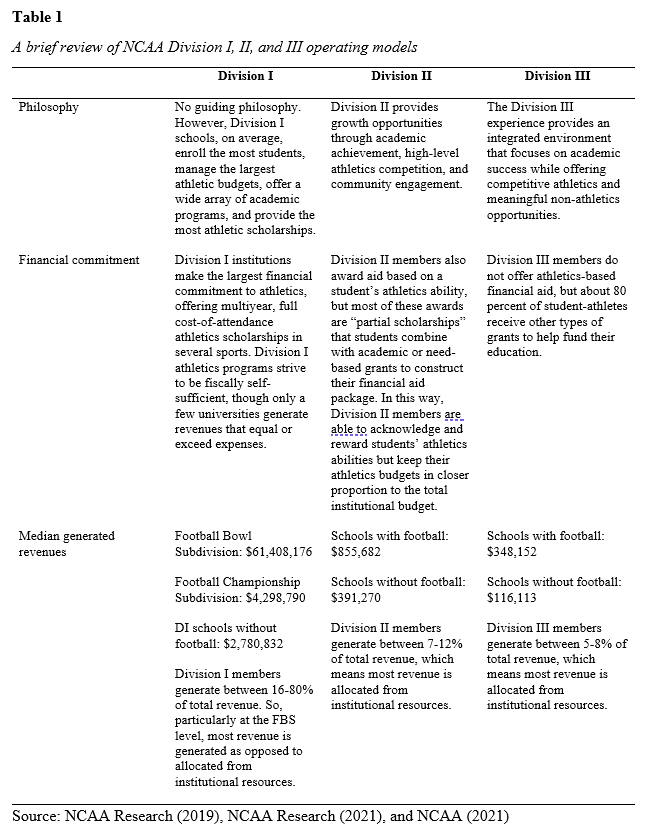

Sport organizations are amid a period of changeable trends in event attendance. At the professional level, the National Football League experienced an uptick of fans across the 2021 season, which ended a three-year decline in reported attendance figures (8). In Division I college football, game attendance data for the Fall 2021 season revealed a continuation of a year-on-year decline dating back to 2014 – the lowest average since 1981 (23). In Division II, men’s basketball tournament attendance is lagging pre-pandemic levels with an average attendance of 916 fans per game at the 2022 tournament versus 1,600 per game at the 2019 tournament (22). Admittedly, and as illustrated in Table 1, revenue generated from event attendance is not a major contributor to the typical funding model of Division II athletic programs, which is dominated by allocated revenue sources including student activity fees and institutional support and not generated revenues such as ticket sales, concessions, and sponsorship (23, 24, 25, 26). However, declining attendance could provide cause for concern for athletic administrators who are striving to demonstrate the added value athletics provides to college campuses still recovering from the financial impact posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like their collegiate Division I and professional sport counterparts, there are certain factors Division II college sport marketers cannot control. As examples, several variables have a significant impact on event attendance at Division II athletic events including winning percentage, stadium age, weather, and student enrollment (5). With regards student enrollment, most Division II schools are in the small (2,999 or fewer) to medium (3,000 to 9,999) size category based on full-time undergraduate enrollment (23), which equates to a relatively small target pool of student fans. Furthermore, most students at Division II schools require extrinsic incentives to increase their awareness of and interest in athletic events (19). Yet, Division II athletic departments have scant resources available from which to offer such incentives. In one study, close to two-thirds of Division II athletic departments were reported as allocating less than $10,000 annually to their sports marketing efforts (41). The National Collegiate Athletic Association recognizes this awareness, interest, and resource deficit and has put in place a game environment initiative at the Division II level to help institutions “establish an atmosphere at home athletics contests that is both energetic and respectful” (23).

To boost product engagement, organizations deploy any number of marketing and promotional activities. Incentives, for instance, provide the final push that moves consumers toward a particular product (34). Sport-based incentives make up a broader range of value-added characteristics (12). On one hand, traditional incentives include marketing tactics where items of perceived as well as real financial value are used to induce consumer action such as premium giveaways and discounts (12). Specifically, sales promotions are marketing tools designed to stimulate quicker and greater purchases for a limited period of time (15). When executed effectively, the benefit of sales promotions for the organization is a sales increase or ‘bump’ during the promotion period (15). As such, sales promotions are considered action-oriented marketing and are often a dominant component of an organization’s marketing efforts (1, 28). In sport, sales promotions are an effective tool for attracting infrequent consumers (12). Sales promotions in sport generally have a price- or non-price-related focus. The most common price-related sales promotions in sport include discounted pricing, coupon redemption, and free trials (12). As an example, in summer 2022, North Texas Athletics launched the “We MEAN Business” ticket campaign with three levels of ticket packages for local businesses that bundled season tickets, parking passes, single game tickets, and merchandise at a discounted price (29).

On the other hand, behavioral response incentives include marketing tactics where the sport product is augmented to better meet the primary motives for sport involvement such as a consumer’s zeal for entertainment (12). As an example, themed events are proven to increase attendance at Division II football games – most notably Homecoming – but also other types of promotional themes such as Parents’ Day and Hall of Fame Day (5). As a result, Division II athletic departments often implement multiple theme games on an annual basis that extend those already listed to include Senior Day, Pink Game, Youth Team Day, and Military Appreciation (8). As such, behavioral response incentives are akin to atmospherics, which refers to all efforts to design buying environments to create specific cognitive or emotional effects in consumers that enhance purchase probability (12). In sport, designing buying environments includes the built features of stadiums and arenas that including retractable roofs, larger seating space, luxury boxes, wait service, hot tubs and swimming pools, picnic areas, and upscale dining facilities (12). However, due in large part to how sport has succumbed to the long-established consumer-driven economy in the United States (7), atmospherics also refers to programmed entertainment that supplements and augments the core product. Such entertainment programming includes dance teams, mascots, and spirit groups (12). At Ohio State University, for example, the dance team performs at athletic event, pep rallies, and parades, and is part of the athletic department’s spirit program alongside the cheerleaders and mascot – Brutus Buckeye (30).

An opportunity exists to better understand what marketing and promotion activities stand to best help stabilize and, ultimately, increase attendance trends in Division II athletics and thus provide an optimal return on the limited marketing-specific investments made by athletic departments. Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to measure the perceived effectiveness of a suite of marketing and promotion activities in persuading and motivating college students – a key internal public – to attend Division II athletic events. This study also sought to understand whether the perceived effectiveness of marketing and promotion activities were related to how frequently college students already attend Division II athletic events. Accordingly, the following research questions were developed to guide the study:

RQ1: What types of marketing and promotion activities are perceived as effective at persuading and motivating college students to attend Division II athletic events?

RQ2: To what extent is the frequency of attendance at Division II athletic events by college students related to the perceived effectiveness of different types of marketing and promotion activities?

METHODS

Participants

The target population was the undergraduate student population at a public university located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Frostburg State University.

Procedures

We used a descriptive research design, which is used to assess a situation in the marketplace like the potential for a specific product (36). Specifically, a paper survey was used as the main instrument. Data collection was completed by 11 undergraduate students as part of a marketing research module within a semester-long sport promotion course. Data collection took place over a two-week period in mid-November 2022. Research participants were recruited using a two-pronged non-probabilistic sampling method where participants were selected consecutively in order of appearance according to their convenient accessibility (17). First, data collectors intercepted students in various common areas around campus. Second, data collectors distributed the survey with instructor permission at the beginning or end of several other undergraduate classes on campus. These courses included those the data collectors were also simultaneously enrolled in during the semester – so were a mixture of major and general education courses.

The survey was primarily designed to evaluate the potential of different marketing and promotion activities on athletic event attendance. The marketing and promotion activities were identified deductively by developing a list of tactics employed within Division II athletics. Specifically, the list was developed by conducting desk research, as well as drawing on the personal experiences of the undergraduate students involved in the data collection. As a result, 17 marketing and promotion activities were identified. Research participants were asked to what extent they were persuaded and/or motivated to attend athletic events due to the presence of these marketing and promotion activities. The survey items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale: 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree with 3=neither agree nor disagree.

In addition, frequency of attendance was measured by asking respondents to enter the number of athletic events they had attended over the first 10 weeks of the Fall semester. For context, a total of 44 home athletic events were hosted on campus during this time. Finally, characteristics of the research participants were captured through four demographic questions – including affiliation with athletics (i.e., student-athlete or student), housing status (i.e., commute, on-campus, or off-campus), class standing (i.e., first year, sophomore, junior, or senior), and gender (i.e., female, male, non-binary/third gender, prefer not to say, or prefer to self-describe – with open response).

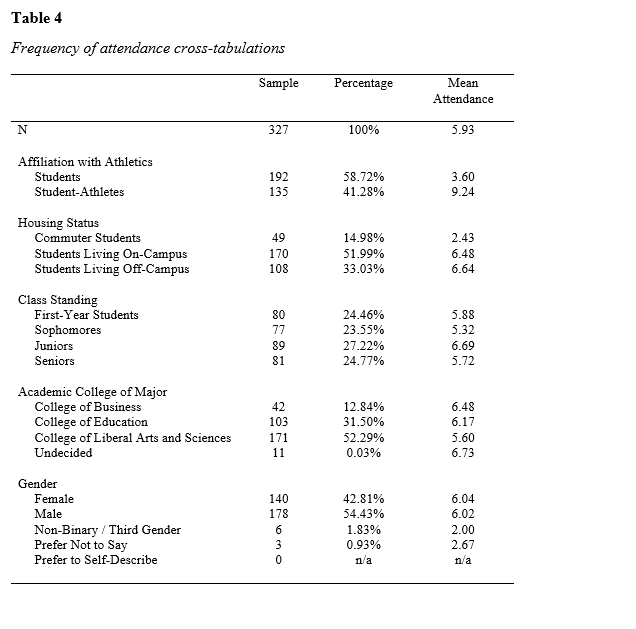

After evaluating completed surveys, 327 were usable and 15 were removed (95.6% completion rate). A representative sample of the residential undergraduate population with 5% margin of error and 95% confidence level was 334 students. As such, the sample was just shy of being representative. However, and as shown in Table 4, respondents were sampled from a variety of classes, majors, living status, and gender.

Data Analyses

To answer RQ1 and assess perceived effectiveness of marketing and promotion activities, mean effectiveness scores for each discreet item were calculated as a starting point. Following this, the 17 items were entered into principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce the variables and improve interpretability while minimizing information loss (40). Finally, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to test for statistically significant differences between the mean scores of the reduced variables following the PCA process. To answer RQ2 and assess the relationship between frequency of attendance (dependent variable) and perceived effectiveness of marketing and promotion activities (independent variables), a Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) was conducted. With the MLR, frequency of attendance was converted to a binary fraction (i.e., a number between 0 and 1), which made frequency of attendance proportionate to the total number of possible athletic event attendances. All statistical tests were completed using IBM SPSS 26.

RESULTS

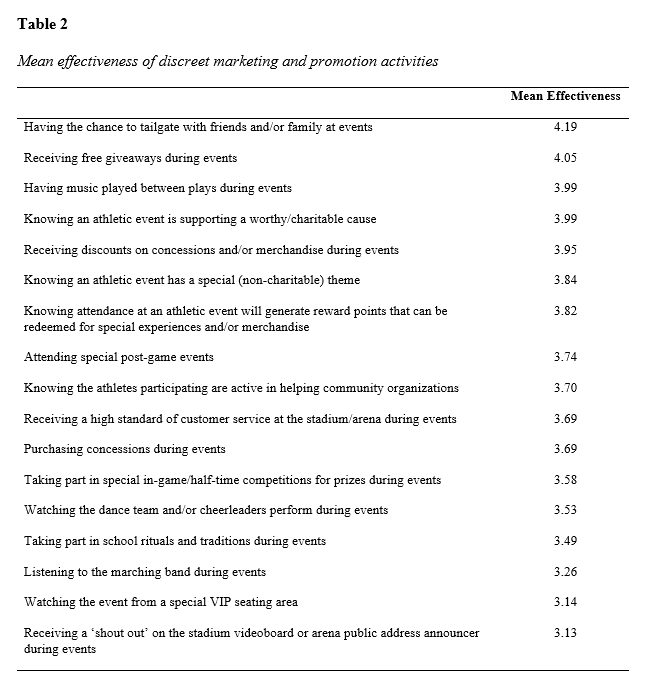

With regards to the perceived effectiveness of discreet marketing and promotion activities, Table 2 presents mean effectiveness in descending order. The opportunity to tailgate with friends and family at games (M = 4.19) was perceived as the most effective effort in persuading and motivating attendance. Whereas, receiving a ‘shout out’ on the stadium or arena videoboard or via the public address announcer (M = 3.13) was perceived as the least effective effort in persuading and motivating attendance. However, all 17 marketing and promotion activities had mean effectiveness scores greater than the midpoint of the five-point Likert scale used (i.e., all marketing and promotion activities were perceived as at least moderately effective at persuading and motivating game attendance).

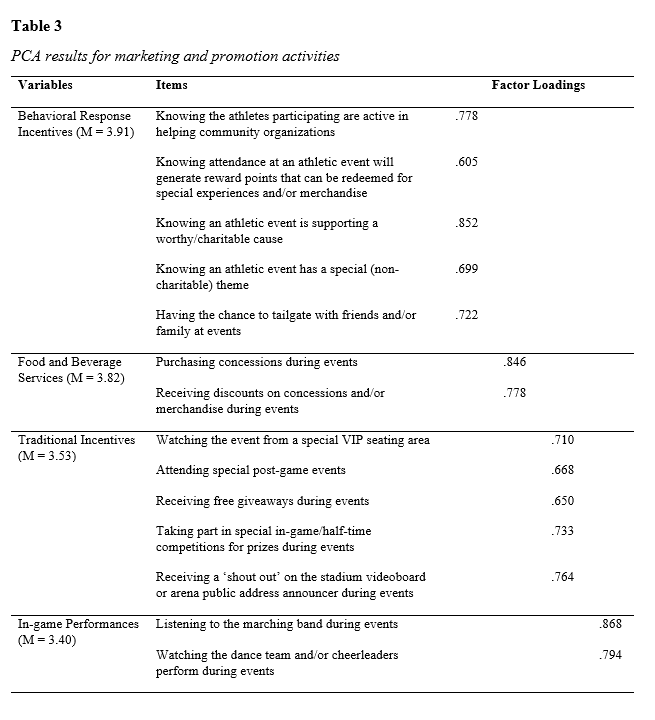

The results of the PCA revealed four components. The KMO measure of 0.885 verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis (13). In addition, Bartlett’s test of sphericity resulted in p-value of less than .001, which indicated the correlations between items were sufficiently large for PCA. Table 2 shows how the components were interpreted conceptually to provide four broad categories of marketing and promotion activities – namely behavioral response incentives, food and beverage services, traditional incentives, and in-game performances. Table 3 also shows the mean effectiveness of each category with behavioral response incentives the perceived most effective (M = 3.91) and in-game performances the perceived least effective (M = 3.40). The result of a one-way ANOVA establishes a statistically significant difference in the mean scores between food and beverage services and traditional incentives (p = 0.0001), but not between behavioral response incentives and food and beverage services (p = 0.2491) nor between traditional incentives and in-game promotions (p = 0.593). As such, the results suggest the most effective types of marketing and promotion activities are those where the sport product is augmented to better meet the primary motives for sport involvement, as well as those that relate to the provision of food and beverages on game days.

Overall, the college students surveyed had attended approximately six athletic events in the semester to date (M = 5.93). Accordingly, the college students surveyed had, on average, attended 13% of the athletic events held during the semester, which was comparable to attendance at an athletic event generally every other week. As is shown in Table 4, significant differences do exist in athletic event attendance across sub-categories of students including between non-athlete students (M = 3.60) and student-athletes (M = 9.24), as well as between commuter students (M = 2.43) and students living either on-campus (M = 6.48) or off-campus (M = 6.64).

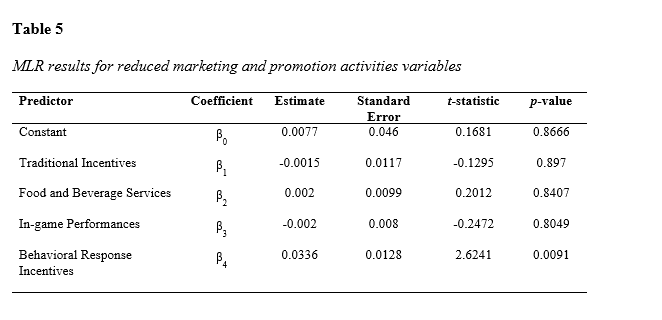

In terms of the relationship between the perceived effectiveness of marketing and promotion activities and existing attendance, Table 5 presents the results of the MLR between frequency of attendance (dependent variable) and the four categories of marketing and promotion activities (independent variables). Only behavioral response incentives were related to frequency of attendance. Specifically, behavioral response incentives were positively related to attendance (p = 0.0091), which means students who had attended the greater number of athletic events – which in the context of this study was student-athletes and students living either on-campus or in off-campus housing close to campus – understood tactics where the sport product is augmented to better meet the primary motives for sport involvement to have an even greater perceived effectiveness. All other categories of marketing and promotion activities were not correlated with frequency of existing attendance at athletic events by college students.

DISCUSSION

Traditional incentives – such as premium giveaways and discounts – are a tried-and-tested tactic at the disposal of the sport marketer. Previous studies have shown that sales promotions have a positive impact on increasing attendance at professional sport events – especially baseball (see 2, 20). Importantly, sales promotions work best in elastic demand situations whereby consumers will do a lot of comparison shopping before making a purchase decision (12). Ultimately, “the more elastic the demand is, the more revenues will increase when the price is reduced” (35, p. 225). Yet, elasticity of demand does not apply for the college student and their intention (or not) to attend Division II athletic events mostly because there is no price to attend. So, altering the price of a ticket is not a tactic the Division II college sport marketer can use to overcome attendance indifference or resistance. The results of this study evidence how traditional incentives, while still moderately effective, are not the most effective means by which to persuade and motivate college students to attend Division II athletic events.

Instead, behavioral response incentives are the types of marketing and promotion activities with the greatest potential to yield an increase in event attendance. As a result, college students appear to place more of an emphasis on the non-price-related factors as their underlying motivations for sport involvement. Specifically, the findings from this study suggest themed games – both charitable and non-charitable – and tailgating to be among the most effective discreet marketing and promotion activities in this category. In turn, these findings suggest college students are persuaded and motivated to attend when efforts are made to augment the core product (i.e., the game) to better emphasize the added entertainment value or the potential for socializing with friends that is on offer. In addition, the relative importance of concessions – both in terms of availability and discounting – is a somewhat surprising surface-level finding considering how for attendees at sporting events concessions are an important part of the game day experience (31). So, while Slavich et al. (33) demonstrate how concessions alone does not motivate spectators to attend professional sporting events, the findings in this study reflect the unique consumer context of college students attending Division II athletic events in facilities where concession opportunities are more limited than at professional sport and even Division I athletics stadia and arena.

At the discrete marketing and promotion activities level, this study both confirms and challenges existing knowledge regarding the Division II game day experience. For example, the results of this study reaffirm how the ritual of tailgating provides opportunities to share the social experience with existing and new friends, as well as family (9). Moreover, this research provides further evidence to support tailgating as an important part of the overall game day experience (27). Yet, the perceived ineffectiveness of marching bands, cheerleaders, and dance teams in contributing to increased attendance in this study is in relative opposition to Natke and Thomas (21) who established that a marching band had a positive impact on attendance at Division II regular season football games.

The main limitation of this study was the single case focus. It is likely that institutional factors unique to the university where the research was collected had a bearing on the results. This should be addressed in future studies by conducting a multi-site or national study to enhance the generalizability of the findings. And while future research should continue to examine the unique context of marketing and promotion at the Division II level, future research should also consider the other side of the coin. So, rather than solely focus on how the game day experience can be enhanced or incentivized to increase attendance, there is a need to better understand the constraints experienced by students that are serving as barriers to greater levels of engagement with Division II athletics on-campus. Simmons et al. (32) conducted such a study, which identified ticket price, seat location, opportunities to socialize, and atmosphere as poignant constraint factors – but the focus was at the Division I level of college athletics. A similar study at the Division II level could elicit some novel findings. For instance, the results of this study raise some questions over lack of attendance at athletic events by commuter students who likely have very different needs and wants to their residential student peers.

CONCLUSIONS

Mason and colleagues (19) suggest that increasing student attendance at Division II athletic events may create a more exciting atmosphere that could, in turn, attract other members of the local community to attend. Yet, the challenge for college sport marketers at the Division II level is establishing a way to maximize limited marketing budgets in a targeted manner to engage these internal publics amid a period of changeable trends in fan attendance. The findings from this study suggest the presence of behavioral response incentives and the availability and discounting of concessions are among the types of marketing and promotion activities that have a greater impact on persuading and motivating college students to attend college sport events. In addition, the findings of this study establish how the effectiveness of marketing and promotion activities is related to existing attendance behavior, but not across the board. Specifically, behavioral response incentives have a potentially greater effectiveness among those college students who already attend athletic events on a regular basis.

Choi et al. (3) suggest college sport marketers at the Division II level should develop a profile of their spectators’ behaviors to ensure promotional activities are targeted. For example, in this study the college students surveyed could have been segmented into four groups based on their attendance behavior: 1) do not attend, 2) attend up to once a month, 3) attend up to once a week, and 4) attend multiple times each week. Furthermore, the positive relationship between frequency of attendance and the effectiveness of behavioral response incentives derived from this study would suggest the Division II college sport marketer should expect such efforts to have a greater impact among those students who already attend regularly – like student-athletes. Therefore, to target non-attendees or infrequent attendees, perhaps the college sport marketer should look at discounting concessions or even traditional incentives (i.e., marketing and promotion activities that are not related to spectator behavior) to increase attendance.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

To provide greatest return on investment, Division II college sport marketers should prioritize efforts to augment the game day experience to fulfill college students’ desire for entertainment and social value; not added monetary value. These marketing and promotion activities include tailgating and themed games – both charitable and non-charitable. Regardless of division, tailgating is an established part of the college football experience. As such, athletic programs should continue to find ways to enhance their football tailgating experiences. For example, Division II Grand Valley State University have launched a Tailgate Town initiative that allows fans to hire a 10’ x 12’ unit with windows, electrical hookup, bar, and flat screen television (10). However, the results of this study suggest the positive impact tailgating has on the football game day experience could also translate to other sports. As an example, a group of parents of soccer players at Division III Birmingham-Southern College have established their own tailgate on a grassy hill overlooking the field (37). The key to the success of the Birmingham-Southern College soccer tailgate is that tailgates do not have to look and feel like a Power 5 college football tailgate to leverage the related sense of community and camaraderie.

Themed games also provide an opportunity to persuade and motivate college students to attend Division II athletic events. Importantly, themed games require the packaging of multiple marketing and promotion activities behind a single theme – including traditional incentives. As a specific example targeted at college students, College of Charleston Athletics offer a Welcome Back to Campus men’s basketball game that includes a pre-game tailgate with the Cougar Activities Board, free bucket hats to the first 350 students in attendance, and a halftime show by an elite dunk team (4). With regards themed games with a charitable focus, Division II college sport marketers should partner with charities that support causes that resonate with college students. For instance, Martinson et al. (18) found that marketing directors at Division I schools noted a positive impact on women’s basketball game attendance because of hosting a Play4Kay or internally developed Pink Night. While not strictly entertainment-based, such promotional games arguably satisfy students’ needs for the sense of emotional wellbeing that accompanies giving back to a worthy cause.

College sport marketers at the Division II level should also prioritize their concession services at athletic events. Not only should Division II athletic events include concessions as a standard aspect of the game day service, but stadia and arena should look to diversify their offerings. Division II Limestone College offered three food trucks and beverage garden as part of their 2023 football spring game (16). In addition to menu options meeting the needs of college students, the results of this study suggest discounting concessions at Division II athletic events could serve as motivation to attend. As an example, TCU offers discounted concessions as part of a Happy Hour that begins 90 minutes before kickoff and ends 30 minutes prior (38). While not strictly a discount, meal swipes – akin to what is offered at Vanderbilt men’s and women’s basketball games (39) – could also be a way to incentivize attendance whereby college students are not having to pay out-of-pocket for concessions.

Ultimately, to provide greatest return on investment, Division II college sport marketers should prioritize efforts to augment the game day experience to fulfill college students’ desire for entertainment and social value; not added monetary value. However, college sport marketers should also develop profiles of their spectators’ behaviors to ensure promotional activities are in fact targeted (3). The segmenting of the student population by attendance behavior while also capturing other key student demographic data has the potential to be an effective means of profiling.

REFERENCES

1. Blattberg, R. C. & Neslin, S. A. (1990). Sales promotion: Concepts, methods, and strategies. Prentice Hall.

2 Browning, R. A. & DeBolt, L. S. (2007). The effects of promotions on attendance in professional baseball. The Sport Journal, 10(3).

3 Choi, Y., Martin, J. J., Park, M., & Yoh, T. (2009). Motivational factors influencing sport spectator involvement at NCAA Division II basketball games. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 3(3), 265-284.

4 College of Charleston Athletics. (2022). 2022-23 men’s basketball student promotions. Retrieved from https://cofcsports.com/sports/2022/10/26/2022-23-mens-basketball-student-promotions.aspx

5 DeSchriver, T. D. & Jensen, P. E. (2002). Determinants of spectator attendance at NCAA Division II football contests. Journal of Sport Management, 16, 311-330.

6 Dodd, D. (2002, February 24). College football attendance declines for seventh straight season to lowest average since 1981. CBS. Retrieved from https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/college-football-attendance-declines-for-seventh-straight-season-to-lowest-average-since-1981/

7 Dyreson, M. (1989). The emergence of consumer culture and the transformation of physical culture: American sport in the 1920s. Journal of Sport History, 16(3), 261-281.

8 Fischer, B. & Broughton, D. (2022, January 11). NFL attendance up, ending three-year decline. Sports Business Journal. Retrieved from https://www.sportsbusinessjournal.com/Daily/Closing-Bell/2022/01/11/NFL-Attendance.aspx

9 Gibson, H., Willming, C., & Holdnak, A. (2002). We’re gators…not just gator fans: Serious leisure and University of Florida football. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(4), 397-425.

10 Grand Valley State Athletics. (2021, June 16). GVSU Athletics announces Tailgate Town for 50th Anniversary of Laker football. Retrieved from https://gvsulakers.com/news/2021/6/16/gvsu-athletics-announces-tailgate-town-for-50th-anniversary-of-laker-football.aspx

11 Gupta, S. (1988). Impact of sales promotions on when, what, and how much to buy. Journal of Marketing Research, XXV, 342-355.

12 Irwin, R. L., Sutton, W. A., & McCarthy, L. M. (2008). Sport promotion and sales management (2nd ed.). Human Kinetics.

13 Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, 31-36

14 Kotler, P. (1974). Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of Retailing, 49(4), 48-64

15 Kotler, P. (1988). Marketing management: Analysis, planning, implementation and control. Prentice Hall.

16 Limestone College Athletics. (2023, April 5). Football announces Spring Game. Retrieved from https://golimestonesaints.com/news/2023/4/5/football-announces-spring-game.aspx

17 Martínez-Mesa, J., González-Chica, D. A., Duquia, R. P., Bonamigo, R. R., & Bastos, J. L. (2016). Sampling: how to select participants in my research study? Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia, 91(3), 326–330.

18 Martinson, D., Schneider, R., & McCullough, B. (2015). An analysis of the factors and marketing techniques affecting attendance at NCAA Division I women’s basketball games. The Sport Journal, 4(2), 42-59.

19 Mason, K., Tucci, J., & Benefield, M. (2017). The best play for NCAA Division II sports marketing is the social media pivot. Journal of Marketing Perspectives, 1, 41-47.

20 McDonald, M. & Rascher, D. (2000). Does bat day make cents? The effect of promotions on the demand for Major League Baseball. Journal of Sport Management, 14(1), 8-27.

21 Natke, P. A. & Thomas, E. A. (2018). Does a marching band impact college football game attendance? A panel study of Division II. Applied Economics Letters, 26(16), 1,354-1,357.

22 NCAA. (2022). Men’s basketball attendance records through 2021-22. Retrieved from http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/stats/m_basketball_RB/2023/Attend.pdf

23 NCAA. (2021). What Division II can do for you. Retrieved from https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/about/d2/tools/D2Abt_WhatDIICanDoForYouBrochure.pdf

24 NCAA Research. (2021). Trends in Division I athletics finances. Retrieved from https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/2021RES_D1-RevExpReport.pdf

25 NCAA Research. (2021). Trends in Division III athletics finances. Retrieved from https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/2021RES_D3-RevExpReport.pdf

26 NCAA Research. (2019). 14-year trends in Division II athletics finances. Retrieved from https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/2019D2RES_D2RevExpReportFinal.pdf

27 Nemec, B. (2011). Customer satisfaction with the game day experience: An exploratory study of the impact tailgating has on fan satisfaction [Master’s thesis, Auburn University]. AUETD. http://etd.auburn.edu/handle/10415/2584

28 Neslin, S. A. (2002). Sales promotion. In B. A. Weitz & R. Wensley (Eds.), Handbook of marketing. Business & Economics, pp. 310-338.

29 North Texas Athletics. (2022, July 1). UNT launches We MEAN Business ticket campaign. Retrieved from https://meangreensports.com/news/2022/7/1/general-unt-launches-we-mean-business-ticket-campaign

30 Ohio State Buckeyes. (n.d.). Ohio State dance team. Retrieved from https://ohiostatebuckeyes.com/dance-team/

31 Seaman, A. N. (2021). Concessions, traditions, and staying safe: Considering sport, food, and the lasting impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. The Sport Journal. Retrieved from https://thesportjournal.org/article/concessions-traditions-and-staying-safe-considering-sport-food-and-the-lasting-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/

32 Simmons, J., Popp, N., & Greenwell, T. C. (2021). Declining student attendance at college sport events: Testing the relative influence of constraints. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 30, 40-52.

33 Slavich, M. A., Rufer, L., & Greenhalgh, G. P. (2018). Can concessions take you out to the ballpark? An investigation of concessions motivation. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 27(3), 167-179

34 Smith, P. R. (1993). Marketing communications: An integrated approach. Kogan Page.

35 Solberg, H. A. & Preuss, H. (2007). Major sport events and long-term tourism impacts. Journal of Sport Management, 21, 215-236.

36 Steber, C. (2018). 3 types of market research: Which does your business need? Communications for Research. Retrieved from https://www.cfrinc.net/cfrblog/types-of-market-research

37 Tailgater Magazine. (n.d.). Tailgate soccer style. Retrieved from https://tailgatermagazine.com/sports/tailgate-soccer-style

38 TCU Athletics. (2022, August 16). TCU Athletics announces changes to gameday. Retrieved from https://gofrogs.com/news/2022/8/16/general-tcu-athletics-announces-changes-to-gameday.aspx

39 Vanderbilt University. (2019, November 18). Vanderbilt campus dining announces meal swipe partnership with athletics. Retrieved from https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2019/11/18/vanderbilt-campus-dining-announces-meal-swipe-partnership-with-athletics/

40 Vasan, K. K., & Surendiran, B. (2016). Dimensionality reduction using Principal Component Analysis for network intrusion detection. Perspectives in Science, 8, 510-512.

41 Zullo, R. (2018). Sports marketing and publicity efforts in Division II intercollegiate athletics. The Sport Journal. Retrieved from https://thesportjournal.org/article/sports-marketing-publicity-efforts-in-division-ii-intercollegiate-athletics/