Authors: Ender SENEL

Corresponding Author:

Ender SENEL, PhD

Mugla Sitki Kocman University Faculty of Sport Sciences

Mugla, 48000

endersenel@gmail.com

0095062001694

Ender SENEL is the research assistant working on sport psychology, teaching and learning in physical education, and moral behaviors in sport in the Physical Education and Sports Teaching Department at Mugla Sitki Kocman University. He is also a member of Sport Sciences Association.

Triadic Relationships Between Interpersonal, Pro/Anti-Social Behaviors, and Moral Disengagement in Team Sports

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between interpersonal, prosocial/antisocial behaviors, and moral disengagement in team sport athletes. This study provided the triadic and linear relationships between interpersonal, prosocial/antisocial behaviors, and moral disengagement in different structural models. 250 team sport athletes including soccer, basketball, volleyball, handball, American football, korfball, and water polo were recruited for the current study. The athletes responded Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire in Sport, Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviors in Sport Scale, Moral Disengagement in Sport Scale-Short. The results showed that athletes’ perception of their coaches’ behaviors can have a significant impact on their moral behaviors in sport.

Key words: interpersonal behaviors, moral disengagement, team sports

INTRODUCTION

For many years, sport research has focused on social (15, 16, 39) and moral (38; 47) dimensions of sports as well as physiological and psychological determinants of performance. The value of moral behaviors in sport has come to prominence with the emphasis on the importance of sports performance. The scientists have shown a crucial interest in the factors leading to or disengage from moral behaviors in sport (29, 32, 33, 34, 40, 50). Moral behaviors in sports have created a broad research field under the concepts of prosocial and antisocial behaviors (1, 19, 24, 28, 35, 42, 46). Immoral behaviors have been examined under the concept related to moral disengagement (13, 24, 25, 48). Prosocial behavior is defined as voluntarily engaged behavior to help or be beneficial for someone (18) while antisocial behavior is voluntarily engaged behavior to hurt or disadvantage someone (35, 46). “Helping a player off the floor” is an example for prosocial behavior in sports while the equivalent for antisocial behavior is “trying to injure an opponent and faking an injury” (30). Prosocial and transgressive behaviors are associated with moral disengagement, which iswhich is related to the individual’s will, and an individual has the freedom to choose moral disengagement or vice versa. The more disengaged from morality, the less displayed prosocial behavior (10, 13). According to Boardley & Kavussanu (13), moral disengagement studies in sport are conducted in two various categories including (a) moral disengagement and behaviors that occur during sports participation; and (b) moral disengagement and doping in sport. Moral or immoral behaviors in sports can be a personal choice as well as a product of environmental factors. By expressing athletes’ social environment has an impact on transgressive behaviors; Long et al. (36) states that the coaches’ pressure on the athletes to cheat cause them to ignore their responsibilities related to behaviors. The following statement shows a clear explanation for the coach’s effect on an athlete:

“We are told to break the rules sometimes, you have to … and simulating is part of the game too. The coach tells you this; when you are in the penalty area, you dribble, if you are hit, you must fall down.”

As it is seen in this statement, the individuals’ behavior can be affected by the behaviors of the people (significant others) they interact (37, 54). According to Bandura (4, 5, 6, 7), environmental factors can direct human behaviors. People intensely interact with their coaches in a sports context. So, the coach’s behaviors, characteristics, and feature may influence behaviors as well as performance (e.g., 20, 31, 37). Especially, the study by Long et al. (36) revealed the effect of coach’s behaviors on the athlete’s behaviors. Accordingly, the athlete’s perceptions, which are related to the coach’s manner, attitude, behavior, and style, can determine the direction of the behavior.

The sports field of interpersonal behaviors studies has gained depth with self-determination theory by Deci & Ryan (17) (44). Self-determination theory assumes that the coaches’ interpersonal behavior styles play an essential role in determining the athletes’ experiences in a sport context, that these behaviors either support or thwart the athletes’ psychological needs (17).

Bandura (9) introduces two distinct aspects, including inhibitive and proactive for morality. The inhibitive aspect is the power to refrain from acting inhumanely. The proactive form of morality is the power to behave humanely. Moral disengagement is associated with prosocial behaviors as well as with transgressive activities. It contributes to social discordance that can lead to dissocial behaviors (10). Prosocial and antisocial behaviors in sport represent proactive and inhibitive behaviors (35, 46). In sports research, moral disengagement has been drawn attention after the Boradley & Kavussanu’s (11) pioneering study. They developed a 32-item measure for moral disengagement and revised this measure with a short form (12). One of the main reason athletes engage in transgressive can be the pressure on them created by the expectation of their coaches and parents for success at all cost (11).

Therefore, moral behaviors or moral disengagement in sport can be a choice as well as the result of an instant decision. At this point, it can be thought that athletes’ perceptions of supportive or thwarting behaviors that are obtained from their coaches can determine the moral or immoral behaviors. The present study examines the relationship between athletes’ perceptions of supportive and thwarting behaviors of their coaches, prosocial and antisocial behaviors, and moral disengagement in sport. The study hypothesizes that the supportive behavior perception of the athletes obtained from their coaches can increase prosocial behaviors, correspondingly moral disengagement decreases, that the effect of prosocial behaviors on decreasing moral disengagement may increase with the supportive behaviors.

METHODS

Participants

The researcher recruited 250 team sport athletes including soccer (n=126), basketball (n=50), volleyball (n=16), handball (n=19), American football (n=29), korfball (n=4), and water polo (n=6). Of the athletes, 17.2% were females (n=43), 82.8% were males (n=207). Of the athletes, 86% were competing in amateur level leagues (n=215). %12.8 reported that they competed for the national team in their branches. The age mean of the athletes is 20.57±3.67, and the experiences mean in their branches is 8.65±4.42. They reported that they trained approximately four days per week (4.06±1.22) and 135 minutes per day (2.13±0.70). The mean score of working with the same coach is 2.19±1.74 while the year with current team is 2.68±1.96.

Measures

Interpersonal Behaviors in Sport

The athletes responded the Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire in Sport (IBQ), developed by Rocchi, Pelletier, and Desmarais (44), adapted to Turkish by Yıldız and Şenel (51). The Turkish form of IBQ, as it is in the original, has 24 items rated between 1 (do not agree at all) and 7 (completely agree). The IBQ consists of six subscales assessing coaches’ use of autonomy-supportive, autonomy thwarting, competence-supportive, competence thwarting, relatedness-supportive, and relatedness thwarting. The measurement is a self-report questionnaire developed to assess interpersonal behaviors between coaches and athletes based on self-determination theory (44). The alpha coefficient of autonomy-supportive, autonomy thwarting, competence-supportive, competence thwarting, relatedness-supportive, and relatedness thwarting in Turkish form is 0.82, 0.71, 0.75, 0.67, and 0.82, 0.66, respectively. In this study, alpha coefficients of AS, AT, CS, CT, RS, and RT were 0.89, 0.83. 0.83. 0.76, 0.85, and 0.74., respectively.

Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviors in Sport

The athletes responded Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviors in Sport Scale (PABSS), developed by Kavussanu and Boardley (30) based on the social cognitive theory of moral and action (8), adapted to Turkish by Balçıkanlı-Sezen (3). The Turkish form of PABSS consists of four subscales (Prosocial Teammate-Pro-T, Prosocial Opponent-Pro-O, Antisocial Teammate-Anti-T, and Antisocial Opponent-Anti-O) including 20 items rated between 1 (never) and 5 (very often). The scale is self-report measurement aiming to assess prosocial and antisocial behaviors in sport. The alpha coefficients in Turkish validation study were 0.70. 0.72, 0.72, and 0.75 for Pro-T, Pro-O, Anti-T, Anti-O, respectively, while the internal consistency coefficients were 0.74, 0.83, 0.71, and 0.75 with the same order in this study.

Moral Disengagement in Sport

The athletes completed the Moral Disengagement in Sport Scale-Short (MDDS-S), developed by Boardley and Kavussanu (12), adapted to Turkish by Gürpınar (21). The scale one-dimensional consisting of 8 items rated between 1 (strongly disagree) and 7 (strongly agree). The scale was developed to assess moral disengagement attitudes in sport. The higher score an athlete gets, the more he/she is morally disengaged in sport (21). The alpha coefficient of the Turkish form was 0.77 while it was 0.79 in this study.

Data Analytic Strategies

Measurement Model

The triadic relationships between Interpersonal Behaviors (IBs), Pro/Anti-social Behaviors (PABs), and Moral Disengagement (MD) in sporting context were evaluated separately in different models hypothesizing the influences of IBS and PAB on MD. The direct effects of PABs on MD and indirect effects on MD via IBS, the direct effects of IBS on MD and indirect effects on MD have been examined in different models. Furthermore, the analyses of the differences included sex, league level, and being international athlete variables. Mean scores of ages, experiences, training day per week, training duration day, the years working with the current coach and in the current team correlated with the mean scores of IBs, PABs, and MD. Also, the correlation analyses included the relationship between IBs, PABs, and MD.

Analyze

The data were analyzed using SPSS and AMOS programs. Normal distribution was checked with Skewness and Kurtosis values. After determining that the data had a normal distribution, the analyses method was chosen. The differences between sexes, athletes in different league level, and international level were analyzed with independent t-test. The relationships between demographical variables and IBs, PABs, and MD were analyzed with the Pearson Correlation. The prediction of MD by IBs and PABs was analyzed with regression analysis. Separately hypothesized models including IBs, PABs, and MD were analyzed in AMOS.

RESULTS

This section presents the findings for demographical information of the athletes, and the correlations and regressions coefficients between scales, the estimates of the hypothesized models.

Table 1. Correlations between Interpersonal Behaviors in Sport, Pro/Anti-Social Behaviors, and Moral Disengagement

| Variables | M. Dis | Anti-B | Pro-B |

| IB-Supportive1 | -0.220** | -0.135* | 0.305** |

| IB-Thwarting2 | 0.237** | 0.200** | -0.285** |

| Prosocial Behaviors3 | -0.295** | -0.433** | |

| Antisocial Behaviors4 | 0.498** |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, 1Mean score of the supportive subscales, 2mean score of the thwarting subscales, 3mean score of prosocial subscales, 4mean score of antisocial subscales

IB-S positively correlated with Pro-B (r=0.305, p<0.01), negatively with Anti-B (r=-0.135, p<0.05). IB-T negatively associated with Pro-B (r=-0.285, p<0.01), positively with Anti-B (r=0.200, p<0.01). MD negatively correlated with IB-S (r=-0.220, p<0.01), positively with (r=0.237, p<0.01). MD also positively correlated with Anti-B (r=0.498, p<0.01). MD negatively associated with (r=-0.295, p<0.01). Correlations between study variables showed that it is proper to conduct mediation analysis to reveal the direct and indirect effects.

Table 2. Regression analysis for twelve models hypothesized between interpersonal behaviors, moral disengagement, and pro/anti-social behaviors in sport

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | The standard error of the Estimate | F Change | Sig. F Change | Standardized β | t | p |

| 1 | 0.3051 | 0.093 | 0.089 | 0.53 | 25.365 | 0.000 | 0.305a | 5.036 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.2201 | 0.049 | 0.045 | 1.22 | 12.653 | 0.000 | -0.220b | -3.557 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 0.1351 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.68 | 4.615 | 0.033 | -0.135c | -2.148 | 0.033 |

| 4 | 0.2852 | 0.081 | 0.077 | 0.53 | 21.848 | 0.000 | -0.285a | -4.674 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.2372 | 0.056 | 0.052 | 1.22 | 14.748 | 0.000 | 0.237b | 3.840 | 0.000 |

| 6 | 0.2002 | 0.040 | 0.036 | 0.67 | 10.285 | 0.002 | 0.200c | 3.207 | 0.002 |

| 7 | 0.3053 | 0.093 | 0.089 | 0.56 | 25.365 | 0.000 | 0.305d | 5.036 | 0.000 |

| 8 | 0.2953 | 0.087 | 0.083 | 1.20 | 23.580 | 0.000 | -0.295b | -4.856 | 0.000 |

| 9 | 0.2853 | 0.081 | 0.077 | 0.55 | 21.848 | 0.000 | -0.285e | -4.674 | 0.000 |

| 10 | 0.1354 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.59 | 4.615 | 0.033 | -0.135d | -2.148 | 0.033 |

| 11 | 0.4984 | 0.248 | 0.245 | 1.08 | 81.803 | 0.000 | 0.498b | 9.045 | 0.000 |

| 12 | 0.2004 | 0.040 | 0.036 | 0.57 | 10.285 | 0.002 | 0.200e | 3.207 | 0.002 |

Predictors: Interpersonal Behaviors-Supportive1. Interpersonal Behaviors-Thwarting2. Prosocial Behaviors3. Antisocial Behaviors4 Dependent Variables: Prosocial Behaviors a, Moral Disengagementb, Antisocial zBehavior, Interpersonal Behaviors-Supportive d, Interpersonal Behaviors -Thwarting e

The first model displays the prediction of prosocial behaviors in sport by supportive interpersonal behaviors. It was found that IB-S predicted Pro-B approximately 9% (R2=0.093, t=5.036, F=25.365, p<0.001). Standardized β shows that the supportive interpersonal behavior in sports increases prosocial behaviors in sport. The second model shows the prediction of moral disengagement by supportive interpersonal behaviors in sport. The results indicated that IB-S predicted MD approximately by 5% (R2=0.049, t=-3.557, F=12.653, p<0.001). According to standardized β value, supportive interpersonal behaviors in sport decrease moral disengagement in sport. The third model includes the prediction of antisocial behaviors in sport by supportive interpersonal behaviors in sport. The results revealed that IB-S also predicted Anti-B by 1% (R2=0.014, t=-2.148, F=4.615, p<0.05). Standardized β value displays that supportive interpersonal behavior in sport decreases moral antisocial behaviors in sport. Fourth, fifth, and sixth models include the prediction of prosocial and antisocial behaviors, moral disengagement in sport by interpersonal thwarting behaviors in sport. IB-T predicted Pro-B (R2=0.081, t=-4.674, F=21.848, p<0.001), Anti-B (R2=0.040, t=3.207, F=10.285, p<0.01), and MD (R2=0.056, t=3.840, F=14.748, p<0.001) approximately by 8%, 4%, and 6%, respectively. According to standardized β values, interpersonal thwarting behaviors in sports increase antisocial behaviors and moral disengagement in the sport while decrease prosocial behaviors in sport. Seventh, eighth, and ninth models show the prediction of moral disengagement interpersonal supportive and thwarting behaviors in sport by prosocial behaviors in sport. Pro-B in sport predicted IB-S (R2=0.093, t=5.036, F=25.365, p<0.001), MD (R2=0.087, t=-4.856, F=23.580, p<0.001), and IB-T (R2=0.081, t=-4.674, F=21.848, p<0.001) approximately by 9%, 9%, and 8%, respectively. According to standardized β values, prosocial behaviors in sports increase supportive interpersonal behaviors in the sport while they decrease interpersonal thwarting behaviors and moral disengagement in sport. Tenth, eleventh, and twelfth models represent the conflicting results of models in which prosocial behaviors in sport are predictors. Antisocial behaviors in sport predicted IB-S (R2=0.018, t=-2.148, F=4.615, p<0.05), MD (R2=0.248, t=9.045, F=81.803, p<0.001), and IB-T (R2=0.040, t=3.207, F=10.285, p<0.05) approximately by 2%, 24%, and 4%, respectively. According to standardized β values, antisocial behaviors in sport decrease supportive interpersonal behaviors in the sport while they increase interpersonal thwarting behaviors and moral disengagement in sport.

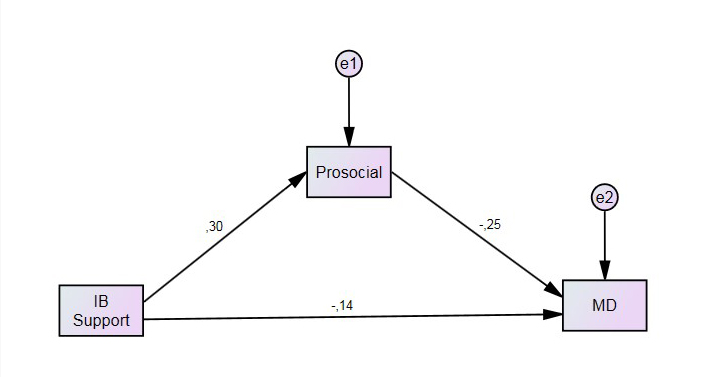

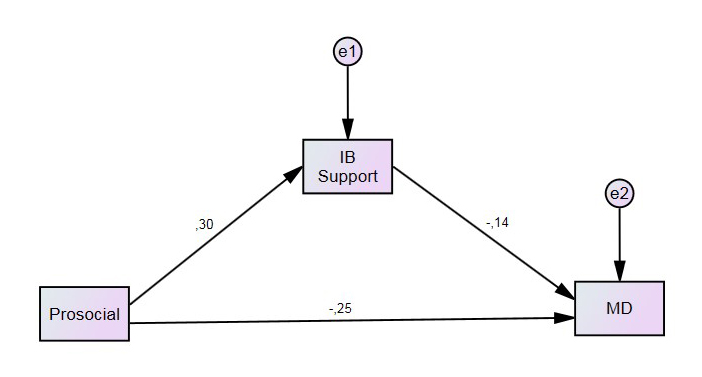

Figure 1. The Triadic relationship model between IB-S, Pro-B, and MD (TR-Model 1)

Table 3. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 1

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| IB-S | Pro-B | .286 | .057 | .305 | *** | |

| IB-S | M. Dis. | .561 | .141 | -.144 | 0.022* | |

| Pro-B | M. Dis. | .302 | .132 | -.251 | *** | |

| IB-S | M. Dis. | Pro-B | between -.146 and -.033 | – | -0.076 | 0.003** |

S.E. Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate, Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-S=Interpersonal Behavior-Supportive, Pro-B= Prosocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 1 displays the relationships between IB-S, Pro-B, and MD in sport. It was hypothesized that IB-S has a direct and indirect effect via Pro-B on MD in sport. Table 3 shows the parameter estimates and significance of these parameters. IB-S had a positive direct effect on Pro-B (R=0.305, p<0.001) and a negative direct effect on MD (R=-0.144, p<0.05). The indirect effect of IB-S on MD via Pro-B is -0.076 (p<0.01), which was calculated by multiplying the regression weights of IB-S/Pro-B and Pro-B/MD. The regression coefficient between IB-S and MD in table 2 is -0.220. In this model, Pro-B is a mediator variable between IB-S and MD by reducing the parameter estimates between these two variables to -0.144. IB-S and Pro-B still decrease MD behaviors in sport.

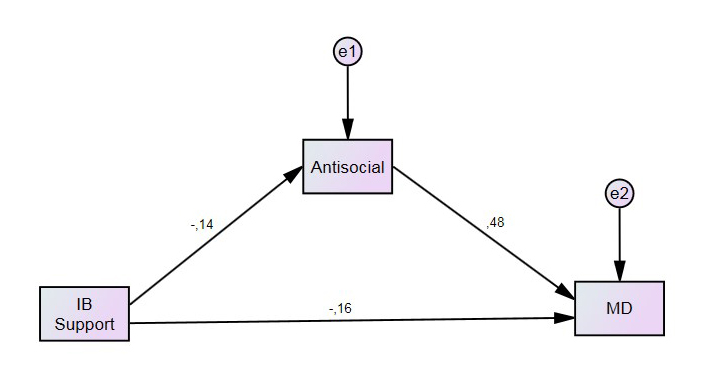

Figure 2. The Triadic relationship model between IB-S, Anti-B, and MD (TR-Model 2)

Table 4. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 2

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| IB-S | Anti-B | -.156 | .073 | -.135 | .031 | |

| IB-S | M. Dis. | -.327 | .115 | -.156 | .004 | |

| Anti-B | M. Dis. | .867 | .099 | .477 | *** | |

| IB-S | M. Dis. | Anti-B | between -.135 and .003 | -0.064 | 0.04 |

S.E.= Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate, Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-S=Interpersonal Behavior-Supportive, Anti-B= Antisocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 2 demonstrates the relationships between IB-S, Anti-B, and MD in sport. The model hypothesizes that IB-S has a direct and indirect effect via Anti-B on MD in sport. Table 4 shows the parameter estimates of the model. IB-S has direct adverse effects both on Anti-B (R=-0.135, p<0.05) and MD (R=-0.156, p<0.01). IB-S indirectly and negatively affects MD via Anti-B in sport (-0.064, p<0.05). IB-S decreases Ant-B and MD as it was found with regression analysis in table 2. The results in table 3 and figure 1 show that IB-S is more effective with the role of Pro-B than Anti-B in sport to decrease MD, which is expected.

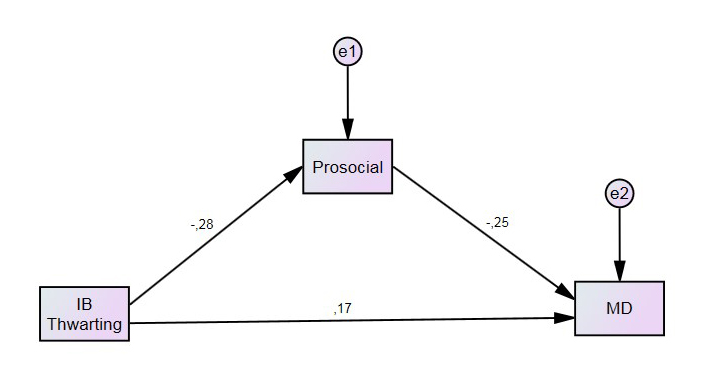

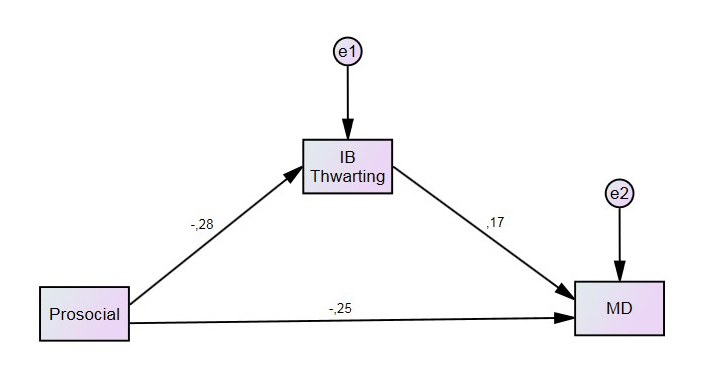

Figure 3. The Triadic relationship model between IB-T, Pro-B, and MD (TR-Model 3)

Table 5. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 3

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| IB-T | Pro-B | -.274 | .058 | -.285 | *** | |

| IB-T | M. Dis. | .359 | .134 | .167 | .007 | |

| Pro-B | M. Dis. | -.553 | .139 | -.247 | *** | |

| IB-T | M. Dis. | Pro-B | between .025 and .139 | 0.070 | 0.006 |

S.E.=Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate, Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-T=Interpersonal Behavior-Thwarting, Pro-B= Prosocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 3 displays the relationships between IB-T, Pro-B, and MD in sport. The model proposes that IB-T has a direct and indirect effect via Pro-B on MD in sport. Table 5 shows the parameter estimates for model 3. IB-T has a negative and direct effect on MD (R=-0.285, p<0.001) while it indirectly affects MD (0.070, p<0.01) via Pro-B. The regression coefficient between IB-T and MD was 0.237. The parameter estimate between IB-T and MD is 0.167, and the indirect effect of IB-T on MD via Pro-B is 0.070. It seems that Pro-B has a role in reducing the effect of IB-T on MD.

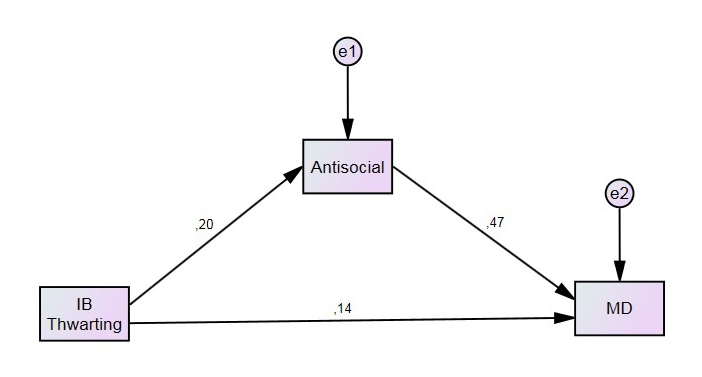

Figure 4. The Triadic relationship model between IB-T, Anti-B, and MD (TR-Model 4)

Table 6. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 4

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| IB-T | Anti-B | .236 | .074 | .200 | .001 | |

| IB-T | M. Dis. | .308 | .119 | .143 | .010 | |

| Anti-B | M. Dis. | .853 | .101 | .469 | *** | |

| IB-T | M. Dis. | Anti-B | between .024 and .172 | 0.093 | 0.007 |

S.E.= Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate, Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-T=Interpersonal Behavior-Thwarting, Anti-B=Antisocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 4 shows the relationships between IB-T, Anti-B, and MD in sport. This model proposes that IB-T has a direct and indirect effect via Anti-B on MD. Table 6 presents the parameter estimates of model 4. IB-T positively and directly affected MD (R=0.143, p<0.05) while it has a positive and indirect impact on MD via Anti-B (0.093, p<0.001). The indirect effect of IB-T on MD is higher when the mediator variable is Anti-B than when it is Pro-B.

Figure 5. The Triadic relationship model between Pro-B, IB-S, and MD (TR-Model 5)

Table 7. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 5

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| Pro-B | IB-S | .325 | .064 | .305 | *** | |

| Pro-B | M. Dis. | -.561 | .141 | -.251 | *** | |

| IB-S | M. Dis. | -.302 | .132 | -.144 | .022 | |

| Pro-B | M. Dis. | IB-S | between -.098 and -.012 | -0.043 | 0.009 |

S.E.=Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate, Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-S=Interpersonal Behavior-Supportive, Pro-B= Prosocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 5 presents the relationship model between Pro-B, IB-S, and MD, proposing that Pro-B has direct effects on both IB-S and MD and indirect effect on MD via IB-S. Table 7 shows the parameter estimates of model 5. Pro-B positively and directly predicted IB-S (R=0.305, p<0.001) and negatively and directly MD (R=-0.251, p<0.001) while it had a negative and indirect effect on MD via IB-S, which the estimate is -0.043 (p<0.01). Pro-B decreases MD in sport, both directly and indirectly via IB-S.

Figure 6. The Triadic relationship model between Pro-B, IB-T, and MD (TR-Model 6)

Table 8. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 6

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| Pro-B | IB-T | -.296 | .063 | -.285 | *** | |

| Pro-B | M. Dis. | -.553 | .139 | -.247 | *** | |

| IB-T | M. Dis. | .359 | .134 | .167 | .007 | |

| Pro-B | M. Dis. | IB-T | between -.112 and -.006 | -0.047 | 0.018 |

S.E.= Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate, Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-T=Interpersonal Behavior-Thwarting, Pro-B= Prosocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 6 shows the relationships between Pro-B, IB-T, and MD, hypothesizing that Pro-B has direct effects on both IB-T and MD and indirect effect on MD via IB-T. Table 8 displays the parameter estimates of model 6. Pro-B has negative and direct impacts on IB-T (R=-0.285, p<0.001) and MD (R=-0.247, p<0.001) while it has a negative direct effect on MD via IB-T (-0.047, p<0.05). In this model, Pro-B still decreases the MD both directly and indirectly by reducing IB-T.

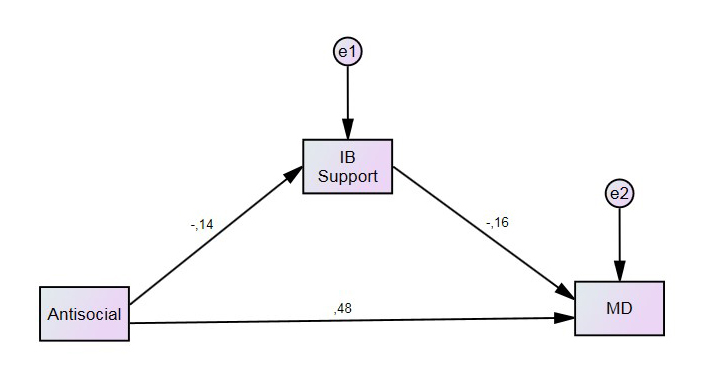

Figure 7. The Triadic relationship model between Anti-S, IB-S, and MD (TR-Model 7)

Table 9. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 7

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| Anti-B | IB-S | -.117 | .054 | -.135 | .031 | |

| Anti-B | M. Dis. | .867 | .099 | .477 | *** | |

| IB-S | M. Dis. | -.327 | .115 | -.156 | .004 | |

| Anti-B | M. Dis. | IB-S | between .000 and .071 | 0.021 | 0.04 |

S.E.= Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate, Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-S=Interpersonal Behavior-Supportive, Anti-B= Antisocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 7 displays the relationship between Anti-B, IB-S, and MD in sport. It was proposed that Anti-B had direct effects on both IB-S and MD and indirect effect on MD via IB-S. Table 9 shows the parameter estimates of model 7. Anti-B directly and positively predicted MD (R2=0.477, p<0.001) while negatively predicted IB-S (R=-0.135, p<0.05). Anti-B had a positive and indirect effect on MD with the role of IB-S (0.021, p<0.05). The regression weight between Anti-B and MD was 0.498 in table 2. It seems that IB-S reduces the effect of Anti-B on MD. However, even with the role of IB-S, Anti-B indirectly increases MD in sport.

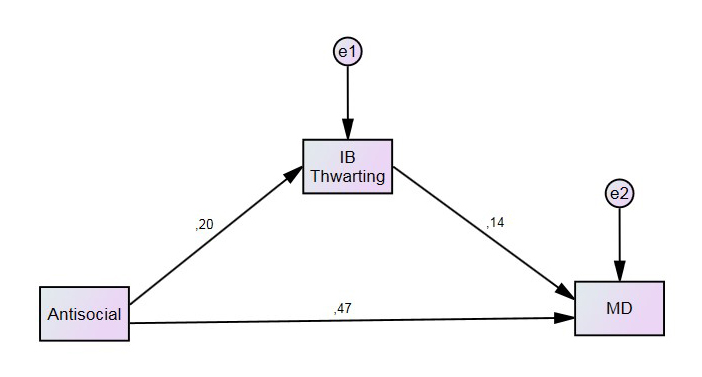

Figure 8. The Triadic relationship model between Anti-S, IB-T, and MD (TR-Model 8)

Table 10. The parameter estimates, standard error, and the P value of TR-Model 8

| Independent | Dependent | Med./Mod. | Est. | S.E. | Std. Est. | p |

| Anti-B | IB-T | .168 | .052 | .200 | .001 | |

| Anti-B | M. Dis. | .853 | .101 | .469 | *** | |

| IB-T | M. Dis. | .308 | .119 | .143 | .010 | |

| Anti-B | M. Dis. | IB-T | between .000 and .086 | 0.028 | 0.015 |

S.E.= Standard Error, Std. Est. = Standardized Estimate., Med./Mod.= Mediator/Moderator, Est.=Estimate, IB-T=Interpersonal Behavior-Thwarting, Anti-B= Antisocial Behavior, M. Dis.= Moral Disengagement

Figure 8 presents the relationship between Anti-B, IB-T, and MD in sport. Table 10 shows the parameter estimates of model 8. This model hypothesized that Anti-B has direct impacts on IB-T and MD and indirect effect on MD via IB-T. Anti-S positively and directly predicted IB-T (R=0.200, p<0.01) and MD (R=0.469, p<0.001). Anti-B had a positive and indirect effect on MD with the role of IB-T (0.028, p<0.05). It is seen that the indirect effect of Anti-B on MD with the role of IB-T is stronger than when the mediator is IB-S.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between prosocial, antisocial, interpersonal behaviors, and moral disengagement in team sports. Triadic models displayed the roles of supportive, thwarting, prosocial, and antisocial behaviors in the prediction of moral disengagement.

The triadic models consisting of interpersonal, prosocial, antisocial behaviors, and moral disengagement in sport context show the roles of the behaviors in predicting moral disengagement. The critical point in these models is the direct and indirect effects of these behaviors on moral disengagement. As both coach and athlete influence their behavior reciprocally (26), the effects of athletes’ perceptions obtained from their coaches on their behavior become prominent in sport context. Coaches’ behaviors have great influences on athletes’ satisfaction (2), motivation (37), and happiness (36). As it is seen in the results, their behaviors, or the perception of athletes for these behaviors can have a great effect on athletes’ moral behaviors. Studies reported that prosocial and antisocial behaviors were associated with personality traits (52) and efficacy beliefs (53).

In the first triadic model, supportive behaviors positively predicted prosocial behavior and negatively moral disengagement directly. Supportive behaviors had a negative indirect effect on moral disengagement. This result should be evaluated with the role of antisocial behaviors in the same model. Supportive behaviors negatively predicted antisocial behaviors, and the direct effect on moral disengagement was -0.156, which was higher than the one in model 1. The indirect impact of supportive behavior was also lower than the first model. Correspondingly, it can be concluded that supportive behaviors more effective with the role of prosocial behaviors than antisocial behaviors in sport to decrease moral disengagement. The supportive behavior perception of team athletes will be more effective in reducing moral disengagement when they are more likely to display prosocial behaviors. The coaches’ behaviors, expectation, most importantly, the athletes’ perceptions seem the key factor for adopting moral behaviors. Considering the adverse effects of thwarting behaviors on moral disengagement, whether directly or indirectly, as it is seen in third and fourth triadic models, the value of the coaches’ supportive behaviors became more critical, because thwarting behaviors can encourage antisocial behaviors and moral disengagement.

Hodge & Lonsdale (23) hypothesized a theoretical model including coaching style, motivation, moral disengagement, and prosocial and antisocial behaviors in sport. According to the results, autonomy supportive coaching style had a weak negative relationship with antisocial teammate and opponent while it was positively associated with prosocial teammate but not with prosocial opponent. It is also reported that the relationship between coaching style and prosocial behavior was mediated by autonomous motivation. Autonomy supportive coaching style had an indirect and positive effect on prosocial behavior while had negative an impact and negative effect on antisocial behaviors. These results are partially consistent with our results.

Prosocial behaviors displayed critical prediction roles in model five and six by reducing the thwarting behaviors and moral disengagement and by fostering supportive behaviors. It can be said that athletes adopting prosocial behaviors may have a positive perception of their coaches’ actions; with that, moral disengagement will decrease. It can also be said that the role of supportive behaviors is an important determinant of reducing moral disengagement.

Mageau and Vallerand (37) included different determinants of the autonomy supportive style in their motivational model to facilitate the development of research programs to foster autonomy-supportive style of coaching for benefits of athletes. The results of present study showed how supportive behavior perception influence moral behaviors and how thwarting behaviors encourage immoral behaviors. It is important to consider that the style or behavior of coaches not only effect the performance and motivation but also moral behaviors. The results of Long et al. (36) are the other evidences how the coaches can affect the moral behaviors in sport. Additionally, Shields et al. (49) reported that while no coaches stated encouraging athletes to cheat or hurt an opponent, some youth athletes reported their coaches did these things. In their longitudinal study, the results of Ntoumanis, Taylor, & Thøgersen-Ntoumani (41) revealed that the intraindividual associations between perceptions of coach’s ego climate and antisocial attitudes including gamesmanship and cheating became significant in time in a positive direction, which indicated that these perceptions could be one of the reasons of antisocial behaviors. Moreover, according to the results of Bolter & Kipp (14), the players’ sense of relatedness to their coaches are more likely to display good behaviors in sport and the players’ perception of the possibility to be punished by the coaches because of displaying immoral behaviors avoid them to engage in antisocial behaviors towards opponents. Additionally, modeled sportsmanship behaviors are other determinants of prosocial behaviors in which teammate relatedness has a great role. Kassim (27) found that athletes’ perception of their coaches’ character building mediated the relationship between coaches’ role model behavior on antisocial opponent behavior (in negative direction). These results are also consistent with the present study.

CONCLUSIONS

The great deal of learning activities occurs in social environment. As learning is a lifelong mental activity, the social influence on learning should be considered for all ages in all contexts. According to Bandura (6, 7), peers are the effective factors in learning activity. Especially in team sports, interactions between peers can determine the direction of the behaviors. The other important factor in learning stated by Bandura is modeling. Sports fields are the place where people can change their behavior from one direction (negative) to another (positive). The stakeholders including coaches, officials, supporters, parents have great responsibilities for the good of the game as well as the athletes. The athletes, especially in early ages, can choose their coaches as their role models. The results of present study highlighted the connections between the perceptions of coaches supportive and thwarting behaviors, prosocial and antisocial behaviors and moral disengagement in team sports. It can be concluded that the coaches have a critical role to encourage athletes’ moral behaviors.

This study also has important implications for coaching education. The coaching education department in universities should consider the moral values in developmental process and include behavior management, fair play, and moral development in their curriculum moral. The education should not be limited with the university but also extended to currently working coaches by organizing seminars with the experts.

REFERENCES

- Al-Yaaribi, A. (2018). Consequences of prosocial and antisocial teammate behaviours for the recipient (Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham).

- Baker, Yardley, & Côté, J. (2003). Coach behaviors and athlete satisfaction in team and individual sports. Int. J. Sport Psychol, 34, 226-239.

- Balcikanli, G. S. (2013). The Turkish adaptation of the prosocial and antisocial behavior in sport scale (PABSS). Int J Humanit Soc Sci, 3(18), 271-6.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall.

- Bandura, A. (1978). The self system in reciprocal determinism. American psychologist, 33(4), 344.

- Bandura, A. (1989a). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American psychologist, 44(9), 1175.

- Bandura, A. (1989b). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Annals of child development. Vol.6. Six theories of child development (pp. 1-60). Greenwich,CT: JAI Press.

- Bandura, A. (1991). Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In W.M. Kurtines & J.L. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development: Theory, research, and applications (Vol. 1, pp. 71–129). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193–209.

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of personality and social psychology, 71(2), 364.

- Boardley, I. D., & Kavussanu, M. (2007). Development and validation of the moral disengagement in sport scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(5), 608-628.

- Boardley, I. D., & Kavussanu, M. (2008). The moral disengagement in sport scale–short. Journal of sports sciences, 26(14), 1507-1517.

- Boardley, I. D., & Kavussanu, M. (2011). Moral disengagement in sport. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4(2), 93-108.

- Bolter, N. D., & Kipp, L. E. (2018). Sportspersonship coaching behaviours, relatedness need satisfaction, and early adolescent athletes’ prosocial and antisocial behaviour. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 20-35.

- Cardenas, A. (2016). Sport and peace-building in divided societies: A case study on Colombia and Northern Ireland. Peace and Conflict Studies, 23(2), 4.

- Coakley, J. (2007). Socialization and sport. The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology.

- Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. In E. Deci & R. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R.A. (1998). Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology. Vol 3: Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 701–778). NY: Wiley.

- Görgülü, R., Adiloğullari, G. E., Tosun, Ö. M., & Adiloğullari, İ. (2018) Prososyal Ve Antisosyal Davraniş İle Sporcu Kimliğinin Bazi Değişkenlere Göre İncelenmesi. Spor Ve Performans Araştırmaları Dergisi, 9(3), 147-161.

- Güllü, S. (2018). Sporcularin antrenör-sporcu ilişkisi ile sportmenlik yönelimleri üzerine bir araştirma. Spormetre Beden Eğitimi Ve Spor Bilimleri Dergisi, 16(4), 190-204.

- Gürpınar, B. (2015). Adaptation of The Moral Disengagement in Sport Scale-Short into Turkish Culture: A Validity and Reliability Study in A Turkish Sample. SPORMETRE Beden Eğitimi ve Spor Bilimleri Dergisi, 13(1), 57-64.

- Hodge, K., & Gucciardi, D. F. (2015). Antisocial and prosocial behavior in sport: The role of motivational climate, basic psychological needs, and moral disengagement. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 37(3), 257-273.

- Hodge, K., & Lonsdale, C. (2011). Prosocial and antisocial behavior in sport: The role of coaching style, autonomous vs. controlled motivation, and moral disengagement. Journal of sport and exercise psychology, 33(4), 527-547.

- Hodge, K., Hargreaves, E. A., Gerrard, D., & Lonsdale, C. (2013). Psychological mechanisms underlying doping attitudes in sport: Motivation and moral disengagement. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35(4), 419-432.

- Jones, B. D., Woodman, T., Barlow, M., & Roberts, R. (2017). The darker side of personality: Narcissism predicts moral disengagement and antisocial behavior in sport. The Sport Psychologist, 31(2), 109-116.

- Jowett, S. & Ntoumanis, N. (2001). The Coach–Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART-Q): development and initial validation. Unpublished manuscript, Staffordshire University, Stoke-on-Trent.

- Kassim, A. F. M. (2018). Athletes’ perceptions of coaching effectiveness in team and individual sport (Doctoral dissertation, University of Birmingham).

- Kavussanu, M. (2006). Motivational predictors of prosocial and antisocial behaviour in football. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(06), 575-588.

- Kavussanu, M. (2019). Understanding athletes’ transgressive behavior: Progress and prospects. Psychology of Sport and Exercise.

- Kavussanu, M., & Boardley, I. D. (2009). The prosocial and antisocial behavior in sport scale. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 31(1), 97-117.

- Kavussanu, M., & Hodge, K. (2018). 10 The coach’s role on moral behaviour in sport. Professional Advances in Sports Coaching: Research and Practice.

- Kavussanu, M., & Spray, C. M. (2006). Contextual influences on moral functioning of male youth footballers. The Sport Psychologist, 20(1), 1-23.

- Kavussanu, M., & Stanger, N. (2017). Moral behavior in sport. Current opinion in psychology, 16, 185-192.

- Kavussanu, M., Roberts, G. C., & Ntoumanis, N. (2002). Contextual influences on moral functioning of college basketball players. The Sport Psychologist, 16(4), 347-367.

- Kavussanu, M., Seal, A. R., & Phillips, D. R. (2006). Observed prosocial and antisocial behaviors in male soccer teams: Age differences across adolescence and the role of motivational variables. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 18(4), 326-344.

- Long, T., Pantaléon, N., Bruant, G., & d’Arripe-Longueville, F. (2006). A qualitative study of moral reasoning of young elite athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 20(3), 330-347.

- Mageau, G. A., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). The coach–athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal of sports science, 21(11), 883-904.

- Miah, A. (2004). Genetically modified athletes: Biomedical ethics, gene doping and sport. Routledge.

- Michelini, E. (2018). War, migration, resettlement and sport socialization of young athletes: the case of Syrian elite water polo. European Journal for Sport and Society, 15(1), 5-21.

- Miller, B. W., Roberts, G. C., & Ommundsen, Y. (2005). Effect of perceived motivational climate on moral functioning, team moral atmosphere perceptions, and the legitimacy of intentionally injurious acts among competitive youth football players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 6(4), 461-477.

- Ntoumanis, N., Taylor, I. M., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2012). A longitudinal examination of coach and peer motivational climates in youth sport: Implications for moral attitudes, well-being, and behavioral investment. Developmental psychology, 48(1), 213.

- O’Brien, K. S., Forrest, W., Greenlees, I., Rhind, D., Jowett, S., Pinsky, I., … & Iqbal, M. (2018). Alcohol consumption, masculinity, and alcohol-related violence and anti-social behaviour in sportspeople. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 21(4), 335-341.

- Rocchi, M., Pelletier, L., & Couture, A. (2013). Determinants of coach motivation and autonomy supportive coaching behaviours. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14, 852–859. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.07.002

- Rocchi, M., Pelletier, L., & Desmarais, P. (2017). The validity of the Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire (IBQ) in sport. Measurement in physical education and exercise science, 21(1), 15-25.

- Sage, L., & Kavussanu, M. (2007). The effects of goal involvement on moral behavior in an experimentally manipulated competitive setting. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(2), 190-207.

- Sage, L., Kavussanu, M., & Duda, J. (2006). Goal orientations and moral identity as predictors of prosocial and antisocial functioning in male association football players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(05), 455-466.

- Sandvik, M. R. (2019). Sport, stories, and morality: a Rortyan approach to doping ethics. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 1-18.

- Shields, D. L., Funk, C. D., & Bredemeier, B. L. (2015). Predictors of moral disengagement in sport. Journal of sport and exercise psychology, 37(6), 646-658.

- Shields, D., Bredemeier, B. L., LaVoi, N. M., & Power, F. C. (2005). The sport behaviour of youth, parents and coaches: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Journal of research in character education, 3(1), 43-59.

- Traclet, A., Romand, P., Moret, O., & Kavussanu, M. (2011). Antisocial behavior in soccer: A qualitative study of moral disengagement. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(2), 143-155.

- Yıldız, M., & Şenel, E. (2018). Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire in Sport Validity and Reliability of Turkish Form. Gazi Journal of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, 23(4), 219-231.

- Yıldız, M., Şenel, E., & Yıldıran, İ. (2018). Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviors In Sport: The Roles Of Personality Traits And Moral Identity. Sport Journal, 42, 1-19

- Yıldız, M., Şenel, E., & Şahan, H. (2015). The relationship between prosocial and antisocial behaviors in sport, general self-efficacy and academic self-efficacy: Study in department of physical education and sport teacher education. Journal of Human Sciences, 12(2), 1273-1278.

- Zimmerman, R. S., & Connor, C. (1989). Health promotion in context: the effects of significant others on health behavior change. Health Education Quarterly, 16(1), 57-75.