Authors: Stephanie Walsh, Nicole Walden, and Tamerah Hunt

Corresponding Author:

Tamerah Hunt, Ph.D., ATC

Department of Health Sciences and Kinesiology

PO BOX 8076

Statesboro, GA 30460

thunt@georgiasouthern.edu

912-478-8620

Stephanie Walsh, BS, ATC is a 2nd year master’s student in the M.S in Kinesiology, concentration in athletic training at Georgia Southern University.

Nicole Walden, BS is a 2nd year master’s student in the M.S in Kinesiology, concentration in sport and exercise psychology at Georgia Southern University.

Dr. Tamerah Hunt, Ph.D., ATC is an Associate Professor and program coordinator of the M.S. Kinesiology concentration in athletic training at Georgia Southern University.

The Effect of Competition Level on Penalties and Injuries in Youth Soccer

ABSTRACT

There are an estimated 3 million youth soccer participants in the United States. As concern rises for the safety of youth athletes, organizations are changing the rules to make the game safer, potentially resulting in more penalized behaviors. Differences in competition levels may contribute to varying numbers of fouls and injuries. PURPOSE: Examine the effect of competition level on the number of fouls and injuries in youth soccer. METHODS: During the competitive season, two soccer organizations were observed to examine behaviors associated with sportsmanship, fouls, and injuries during a game situation. The organizations consisted of teams from a recreation department and a travel academy soccer club located in South Georgia. Teams consisted of male and female athletes ranging from 6-16 years old, whom were divided by pre-determined age groups within the leagues. Observational data was collected on game statistics which included spectator, coach and athlete behavior, as well as fouls and injuries, within the soccer organizations. A total of 86 recreational (n=52) and club (n=34) games were observed. RESULTS: Club soccer teams had a greater number of fouls (n=224, mean ± SD 1.22 ± 1.28, ranging from 0-18) compared to recreational teams (n=61, mean ± SD 1.22 ± 1.28, ranging from 0-5). The number of injuries were not affected by the level of competition in club (n= 26; 0.76 + 0.99, ranging from 0-3 per game) and recreation (n=27; mean ± SD 0.53 ± 0.83, ranging from 0-3) youth soccer teams. CONCLUSION: This pilot study provides preliminary evidence that competition level may be the driving force of behaviors that lead to penalties. Regardless of the number of penalties for both organizations, the number of injuries were minuscule; thus, severing the link between aggressive behaviors and injury in youth soccer. Therefore, it seems that a greater level of competition in youth soccer leads to more fouls, but not more injuries. Future research should consider situational factors that may impact these findings such as coaches and parent’s behaviors throughout the game.

Key words: rule violations, children, recreation league, club league

INTRODUCTION

The popularity of soccer has led to a rise in youth participation in soccer, with estimated 3 million youth soccer participants in the United States (32). As youth athletes continue to participate in soccer, concern undoubtedly rises for the safety of players. The Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) has taken steps to address this concern through organizational structure and fair play since 1997 (12). FIFA enforces the laws of soccer throughout the world and oversees all soccer organizations such as the United States Soccer Federation (U.S. Soccer) that governs all US soccer organizations and leagues (6,11). Soccer organizations and leagues are required to follow the rules and organizational structure of soccer including laws that determine the division of teams and competition levels among organizations and leagues (8,11,31).

The level of competition is a key variable in soccer games, but it is also important to recognize the diversity in definitions for levels of competition (i.e., club, recreational) between different countries and leagues. Club soccer focuses on high skill and player development with an emphasis on high-level competition and travel (25) whereas recreational soccer is characterized by enjoyment and development of soccer players without the emphasis on travel or high-level competition (2). Despite the differences in competition level and developmental goals, similarities exist in terms of league organization.

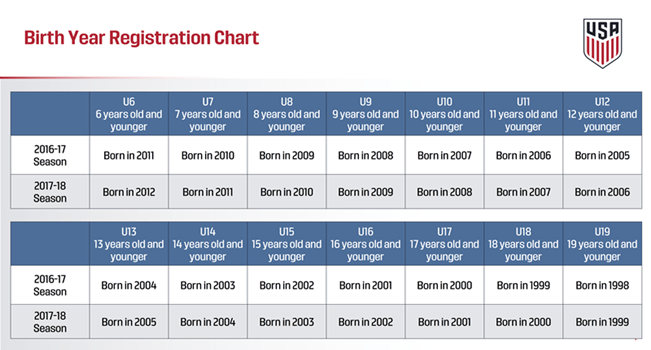

Each league organizes teams within each competition level by age (31). Age groups were previously determined by the traditional school year calendar, from August to July for the soccer season. However, starting in the 2017-2018 season, FIFA ruled age groups needed to be determined by each player’s birth year, as determined by the year a soccer season ends (31). An age group can be determined by subtracting the birth year from the year the season ends which is represented in Figure 1 provided by U.S. Soccer (31). The birth registration rule was created to reduce the relative age effect, which is a selection bias towards players born earlier in the calendar year (31). Naturally, older and more mature players are often selected due to size (31). Therefore, predetermined age groups were implemented to ensure appropriate athlete development and regulate fair play between athletes and teams.

FIFA has promoted fair play in soccer leagues and organizations since 1997 to address the safety concern in youth soccer (12). Fair play includes respecting others (referees, players, opponents, fans) and playing according to the rules of the game (12). On the other hand, foul play is defined as “the act of playing unfairly or doing something that is against the rules” (4). According to FIFA’s Laws of the Game (11), a foul in soccer is an infringement of the rules punished by the award of a free kick or penalty kick to the opposing team. Fouls are further characterized as the use of excessive force and careless or reckless offences on opponents by players or teams (14). Referees use yellow and red cards to signify the occurrence of foul play to minimize the number of unsafe actions that expose a player to high risk situations that could cause potential injuries (11,14).

Despite the consequences of foul play, purposeful rule violations are still occurring to gain advantages in the game (14). More purposeful rule violations are seen as competition level increases (14). Silva (28) suggested that as experience is gained in a sport, tolerance of certain sports norms regarding rule violation(s) (i.e., committing a foul for a team advantage) can develop. Shields and Bredemeier (27) further explained that purposeful rule violations are responses to the competitive nature of sports that persuade players to aim for personal or team advantages over one’s opponents at any means necessary.

Several studies have examined a player’s willingness to commit an intentional foul in a soccer game (17, 22 and 23). Ryynänen and colleagues (23) found that 90% of players admitted that they were willing to commit an intentional foul if required or asked. Likewise, Junge (17) found that half of youth players consider intentional fouls as a regular part of the game, and that the acceptance of these rule violations increase with age and experience. This justifies concern since violations may lead to overtly aggressive plays, often exhibited in terms of fouls (14, 20 and 24). Foul play has been considered one of the most important extrinsic factors leading to soccer injuries (12).

Foul play was found to be involved in 47% of all youth soccer injuries (20). Injuries caused by foul play in youth soccer are mostly acute contusions, sprains, and muscular strains affecting the lower extremities of the body (9,13,14,18,19 and 21). Several studies have reported that half of the injuries in youth soccer occur from foul play that involve player-to-player contact such as tackling or heading (9,13,16,18 and 19). This suggests that more fouls that are purposeful may lead to more body contact, producing more injuries. Sapp and colleagues (24) suggested that the increased risk of injuries from fouls may be due to referees identifying overtly aggressive plays as fouls. This is concerning since injuries resulting from fouls can be prevented by following the laws of soccer (11,14). Research examining the relationship between the number of fouls and injuries across competitive soccer games has been inconsistent. Some researchers have found as the level of competition rises, more fouls and injuries occur (9, 22), while other studies have found that as competition level rises there is an increase in fouls, but a decrease in injuries (21, 26). The inconsistency could be due to the variation in methods used to record injuries and fouls, the definitions used for fouls and injuries, and sample characteristics, such as skill level, which prompts for further research to be conducted. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to examine the effect of competition level on the number of fouls and injuries in youth soccer. Based on previous research regarding competition level and the number of fouls and injuries, the researchers hypothesized that the number of fouls and injuries would increase as the competition level increases. Specifically, we expected recreational soccer teams to exhibit fewer fouls and injuries in games compared to club soccer teams.

METHODS

This study is a cross-sectional descriptive study.

Participants

Participants included two soccer leagues located in South Georgia, comprised of male and female athletes from the ages of six to sixteen years old. A total of eighty-six youth club and recreational soccer games were observed.

Procedures

Prior to data collection, each league was contacted and informed of the study, and permission to observe games was gained. All researchers completed the Washington State referee-training course to understand the rules and signaling of fouls and penalties. Additionally, researchers were trained on how to complete the observation guide during games prior to any data collection. Researchers attended all games and watched in its entirety to observe player, coach and spectator behavior, fouls and penalties committed, score and injuries during the game. Each game lasted approximately one hour to 90 minutes, depending on the level of competition. A total of eighty-six club and recreational games were observed across both leagues (34 club, 52 recreational). Data was collected on game statistics such as fouls and injuries, utilizing observation guides in real time as the game progressed. Additionally, researchers used fouls and penalty cards (i.e., red cards, yellow cards) as identifiable factors to measure aggressive play (3, 5, 15 and 24). Fouls were identified as yellow cards, red cards, penalty kicks conceded, direct kicks conceded, indirect kicks conceded, and advantages called by the referee. Injuries were identified as an injury stoppage or player removed from the field. Total numbers of fouls, penalties, and injuries were tallied during the game and totaled at the completion of the game.

Data Analysis

The observational data was entered into SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Prior to data analysis, all data was examined for outliers, homoscedasticity, and normality. Injury and foul data that deviated by two standard deviations from the mean were considered outliers and removed from the data set (four games). The data violated homoscedasticity and normality, therefore a one-way ANOVA could not be performed to determine whether fouls and injuries differed between competition levels. Descriptive statistics were used to examine the effect of competition level on the occurrence of fouls and injuries in youth athletes. Frequency counts, standard deviations, ranges, and means were reported for fouls and injuries within each competition level as well as total fouls and injuries.

RESULTS

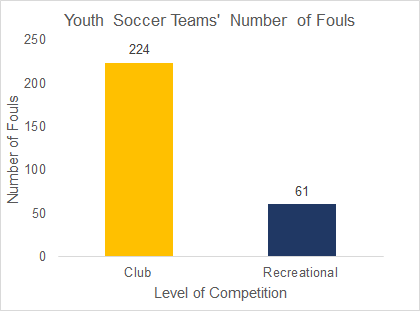

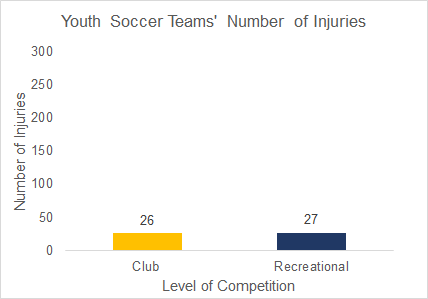

Descriptive statistics for fouls and injuries can be found in Table 1. Overall, club soccer teams had a greater number of fouls (n=224, mean ± SD 1.22 ± 1.28, ranging from 0-18) compared to recreational teams (n=61, mean ± SD 1.22 ± 1.28, ranging from 0-5) which is demonstrated in Figure 2. The number of injuries were not affected by the level of competition in club (n=26; mean ± SD 0.76 ± 0.99, ranging from 0-3 per game) and recreational (n=27; mean ± SD 0.53 ± 0.83, ranging from 0-3) youth soccer teams. The average number of injuries per game was negligible, averaging less than one injury per game for both club and recreational teams (Figure 3).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of total fouls and injuries observed during recreational and club youth soccer games

| Fouls | Injuries | |||

| Mean + SD | Range | Mean + SD | Range | |

| Recreational | 1.22 ± 1.28 | 0-5 | 0.53 ± 0.83 | 0-3 |

| Club | 6.79 ± 4.78 | 0-18 | 0.76 ± 0.99 | 0-3 |

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of competition level on the number of fouls and injuries in youth soccer. Our results support the hypothesis that the number of fouls increased as the competition level increased. Interestingly, our results did not support the hypothesis that the number of injuries will increase as the competition level increases or that recreational soccer teams will exhibit fewer injuries during games compared to club soccer teams. Overall, a greater level of competition resulted in an increase in fouls. Our findings are consistent with previous research, supporting that an increase in competition level results in more penalties and fouls (8,15). Gómez-Deniz and Dáavila-Cárdenes (15) found an increased number of penalties, displayed as red and yellow cards, when competition level increased. Overall, our results demonstrated that as the level of competition increased in club and recreational youth sports, penalties and fouls also increased in games.

Consistent with previous research, the increase in penalties and fouls during games may be linked to purposeful rule violations (14, 20, 23 and 24). Several studies found that players engage in aggressive behaviors as a tactical strategy to gain advantages or as an emotional response to a situation (8,10). Some researchers believe that a higher level of competition exhibits fewer aggressive behaviors than those playing at lower levels, due to the tactical actions leading to better control and performance, thus showing less fouls and aggressiveness (1,7). Although a greater level of competition may cause behaviors that lead to penalties, those behaviors did not lead to an increased occurrence of injuries.

Despite the high rate of contact that occurs in soccer, injuries were infrequent. Our results indicated injuries averaged less than one injury per game for both club and recreational youth soccer teams. This is consistent with other research that found low incident rates of injuries within youth sports. Several researchers report incident rates ranging from 0.5-13.7 injuries per 1000 hours of exposure (21, 29). Similarly, Giza and Micheli (14) examined characteristics and incidence rates of soccer injuries in a youth population and found, on average, 2.3 injuries occurred per 1,000 practice hours and 14.8 injuries occurred per 1,000 game hours. However, Peterson et al. (21) found that lower-level youth players experienced twice as many injuries as higher-level players, due to less exposure time of practices and games.

It was theorized that exposure to in-game soccer play decreased in lower-level groups, leading to underdeveloped skills compared to higher-leveled players (19, 26). Therefore, underdeveloped skills, such as weaknesses in techniques, tactics, muscle strength, endurance, and coordination, could lead to more frequent injuries in lower-level groups compared to higher-level players (27). More so, lower-level athletes tend to have less control of their bodies, resulting in increased body contact. Previous research has found that more than 50% of injuries are caused by body contact, providing supporting evidence that underdeveloped skills in lower-level players may lead to more injuries (27). Researchers state that better conditioning, techniques, and tactics may allow for reduction in injuries in higher-level players compared to less experienced players who have a weakness in technique, endurance, and coordination (21,27). More so, research has found that players in higher levels have twice as many training hours than lower level players, thus displaying greater technique, skill, and physical improvement (i.e., muscle strength, endurance, and coordination), allowing for players to meet the demands of playing games with fewer injuries (16, 19 and 26). Although research has provided evidence of the occurrence and reasoning behind injuries, our results suggested that injuries were not determined by the level of competition.

This study is not without limitations that could influence our results. The main limitation is the observational nature of the study. The data was observed by several researchers involved in the study. To avoid reliability issues in data collection, each researcher was trained in observation of the rules of the game and appropriate referee signals prior to the study. A second limitation existed as foul data was only recorded when the referees called the fouls, meaning fouls may have occurred throughout the games that referees did not see or call. Therefore, the number of fouls reported within this study might be underestimated in games.

CONCLUSIONS

A greater level of competition has resulted in more fouls, while the level of competition in youth soccer games did not affect the number of injuries. Our findings support that a greater level of competition may cause behaviors that lead to penalties, but those behaviors did not lead to an increased occurrence of injuries. While we found that competition level appears to affect fouls, but not injuries, future research should examine what other factors can influence the numbers of fouls and aggressive behaviors occur during youth soccer. Specifically, researchers should examine the relationship between coach and parent behaviors, which may influence the behaviors leading to fouls and injuries.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

Organizations have modified the rules to make the game safer, as concern has risen for the safety of youth athletes. Varying levels of competition in sports are required to follow an array of rules regarding their specific age and skills. Our research provides evidence that a greater level of competition resulted in increased number of fouls but did not result in an increase number of injuries. In fact, we found miniscule numbers of injuries, indicating youth sports are generally a safe environment for those participating.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Centers for Disease Control Grant: CE17-002

REFERENCES

- Albrecht, D. (1982). Empirical research into aggression in sport: Diagnosis of a diagnosis. In G. Pilz & al. (Eds.), Sport and violence (pp. 97-124). Schomdoff-Hofmann.

- Bulloch Parks and Recreation (n.d.). Soccer. https://www.savannahunited.com/Default.aspx?tabid=324550

- Buraimo, B., Forrest, D., & Simmons, R. (2010). The 12th man? Refereeing bias in English and German soccer. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 173(2), 431–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2009.00604.x

- Cambridge English Dictionary (n.d.). Foul play: Definition in the Cambridge English dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/foul-play

- Carmichael, F., & Thomas, D. (2005). Home-field effect and team performance: Evidence from English premiership football. Journal of Sports Economics, 6(3), 264–281.

- Challenger Sports (n.d.). How soccer in the US is organized!

https://www.challengersports.com/soccer-us-organized/ - Costa, I.T.D, Garganta, J., Greco, P.J., Mesquita, I., & Afonso, J. (2010). Assessment of tactical principles in youth soccer players of different age groups. Revista Portuguesa de Ciências do Desporto, 10(1), 147-157. doi:10.5628/rpcd.10.01.147.

- Coulomb, G., & Pfister, R. (1998). Aggressive behaviors in soccer as a function of competition level and time: A field study. Journal of Sport Behavior, 21(2), 222–231.

- Emery, C. A., Meeuwisse, W. H., & Hartmann, S. E. (2005). Evaluation of risk factors for injury in adolescent soccer: Implementation and validation of an injury surveillance system. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 33(12), 1882–1891. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546505279576

- Fields, S.K., Collins, C.L., & Comstock, R.D. (2010). Violence in youth sports: Hazing, brawling and foul play. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 44(1), 32-37. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.068320.

- FIFA (2018). Education & technical referees: Laws of the game.

www.fifa.com/development/education-and-technical/referees/laws-of-the-game.html - FIFA (n.d.). Welcome to FIFA.com news: FIFA’s fair play day. https://www.fifa.com/news/fifa-fair-play-day-70207

- Gaspar-Junior, J. J., Onaka, G. M., Barbosa, F. S. S., Martinez, P. F., & Oliveira-Junior, S. A. (2019). Epidemiological profile of soccer-related injuries in a state Brazilian championship: An observational study of 2014–15 season. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma, 10(2), 374–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2018.05.006

- Giza, E., & Micheli, L. J. (2005). Soccer injuries. Epidemiology of Pediatric Sports Injuries, 49, 140–169. https://doi.org/10.1159/000085395

- Gómez-Deniz, E., & Dáavila-Cárdenes, N. (2017). Factors influencing the penalty cards in soccer. Electronic Journal of Applied Statistical Analysis, 10(3), 629–653. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20705948v10n3p629

- Heidt, R. S., Sweeterman, L. M., Carlonas, R. L., Traub, J. A., & Tekulve, F. X. (2000). Avoidance of soccer injuries with preseason conditioning. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 28(5), 659–662.

- Junge, A. (2000). The influence of psychological factors on sports injuries. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 28(5), 10–15.

- Junge, A., Chomiak, J., & Dvorak, J. (2000). Incidence of football injuries in youth players: Comparison of players from two European regions. American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, 28(5), 47–50.

- Junge, A., Rosch, D., Peterson, L., & Dvorak, J. (2002). Prevention of soccer injuries: A prospective intervention study in youth amateur players. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 30(5), 652–659.

- Junge, A., & Dvorak, J. (2013). Injury surveillance in the world football tournaments 1998-2012. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(12), 782–788.

- Peterson L, Junge A, Chomiak J, Graf-Baumann T, & Dvorak J. (2000). Incidence of football injuries and complaints in different age groups and skill-level groups. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 28, 51-57. doi:10.1177/28.suppl5.s-51

- Romand, P., Pantaleon, N., & D’Arripe-Longueville, F. (2009). Effects of age, competitive level and perceived moral atmosphere on moral functioning of soccer players. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 40(2), 284–305.

- Ryynänen, J., Junge, A., Dvorak, J., Peterson, L., Kautiainen, H., Karlsson, J., & Börjesson, M. (2013). Foul play is associated with injury incidence: An epidemiological study of three FIFA world cups (2002–2010). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(15), 986–991. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092676

- Sapp, R. M., Spangenburg, E. E., & Hagberg, J. M. (2019). Markers of aggressive play are similar among the top four divisions of English soccer over 17 seasons. Science & Medicine in Football, 3(2), 125–130.

- Savannah United. (n.d.). Academy program: Savannah united academy. https://www.savannahunited.com/Default.aspx?tabid=324550

- Schwebel, D. C., Banaszek, M. M., & McDaniel, M. (2007). Brief report: Behavioral risk factors for youth soccer (football) injury. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(4), 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsl034

- Shields, D., & Bredemeier, B. (1984). Sport and moral growth: A structural developmental perspective. In W. Straub & J. Williams (Eds.), Cognitive sport psychology (pp. 89-101). New York: Sport Science Associates.

- Silva, J. M. (1983). The perceived legitimacy of rule violating behavior in sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 5(4), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsp.5.4.438

- Sullivan, J. A., Gross, R. H., Grana, W. A., & Garcia-Moral, C. A. (1980). Evaluation of injuries in youth soccer. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 8(5), 325–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354658000800505

- Thomas, S., Reeves, C., & Smith, A. (2006). English soccer teams’ aggressive behavior when playing away from home. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 102(2), 317–320.

- U.S. Soccer (2017). Five things to know about birth year registration. https://www.ussoccer.com/stories/2017/08/five-things-to-know-about-birth-year-registration

- U.S. Soccer (2019). US youth soccer statistics infographic: Rapids youth soccer club. http://rapidsyouthsoccer.org/us-youth-soccer-player-statistics/