Author: Tayleigh Talmadge MAT, ATC

Corresponding Author:

Valerie Moody PhD, LAT, ATC

32 Campus Dr. McGill 205

HHP Department

Missoula, MT 59812

406-243-2703 (office)

valerie.moody@umontana.edu

Tayleigh Talmadge is a recent graduate of the Masters in

Athletic Training Program at the University of Montana. Valerie Moody is a

Professor and Program Director of the Athletic Training Program at the

University of Montana.

Aggressive Osteoblastoma of the Acetabulum in an 18-Year-Old Female Volleyball Player

Abstract

In a case study, an 18-year-old female volleyball player presented with persistent hip pain. Imaging revealed a lesion in the acetabulum and follow up biopsies led to the diagnosis of a benign osteoblastoma. The patient underwent a surgical resection and open reduction internal fixation of the acetabulum. Aggressive osteoblastomas of the acetabulum are rare in a young, active population; therefore, clinicians must be able to recognize the need to refer for further evaluation and understand the importance of a multidisciplinary individualized plan of care to ensure a successful return to play for the patient.

Keywords: osteoblastoma, acetabulum, athlete

Introduction

An osteoblastoma is a rare bone tumor found in the medullary cavity or on the surface of long bones and posterior elements of the spine (12,14) Osteoblastomas represent about 0.8% of all bone tumors and are more commonly seen in male adolescents (11,12). There are many clinical and histological similarities to a benign osteoid osteoma, but osteoblastomas are typically much larger in size (>1.5-2.0 cm) (14). Osteoblastomas are naturally benign but may exhibit aggressive behavior (11). An aggressive osteoblastoma is a rare tumor that represents a borderline lesion between a benign osteoblastoma and cancerous osteosarcoma (11). Physical presentation of an aggressive osteoblastoma of the hip includes limited range of motion (ROM), chronic pain, night pain, radiating pain, pain aggravated by weight-bearing or walking, and pain alleviated by analgesic drugs (5,9,11,12,14). Osteoblastomas in the region of the hip are rarely encountered, especially an aggressive osteoblastoma of the acetabulum as presented in this case (11,14).

There are three stages in osteoblastoma development. Stage 1 lesions are latent; Stage 2 lesions are active; and Stage 3 lesions are aggressive osteoblastomas (5). Surgical treatment of an osteoblastoma of the acetabulum involves complete excision of the lesion (5,9,12,14). For Stage 1 and 2 lesions, the recommended treatment is extensive intra-lesioned curettage and packing of the defect with a bone graft (5,9). For Stage 3 lesions, wide resection is performed, which involves excision of the tumor along with surrounding edges of normal bone and soft tissue (5). Post-surgical complications, such as infections and blood clots, are common in patients following a total hip or knee arthroplasty, so it can be inferred that tumor excisions would result with similar occurrences (13). Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the most frequently identified pathogen following such invasive procedures (13). Unfortunately, there is little research regarding S. aureus infection prevalence following a resection of an osteoblastoma.

Incidence of osteoblastoma in young, active populations is rare resulting in little knowledge regarding specific osteoblastoma return-to-play outcomes. It is pertinent to all clinicians working with an athletic population to recognize early signs and symptoms, know when to refer, and develop a multidisciplinary individualized plan of care for an athlete suffering of a non-sport specific condition. The purpose of this case study is to discuss the assessment, treatment, and recovery of an 18-year-old Caucasian female volleyball player diagnosed with an aggressive osteoblastoma of the acetabulum of the hip.

Athlete Presentation

The athlete first recognized pain in her right hip during her junior year of high school volleyball. She presented with a chief complaint of deep, aching pain from her outer hip to upper groin. Intermittent pain progressed over the course of a year and a half later to persistent pain every day. Pain management consisted of over the counter pain relievers for a year and a half. Despite the pain, the athlete was able to compete throughout her senior year of high school volleyball without limitation. She was recruited to play collegiate volleyball and was expected to begin play in the fall following high school graduation.

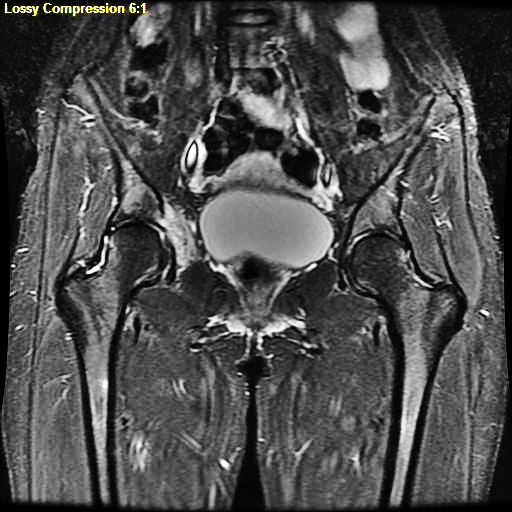

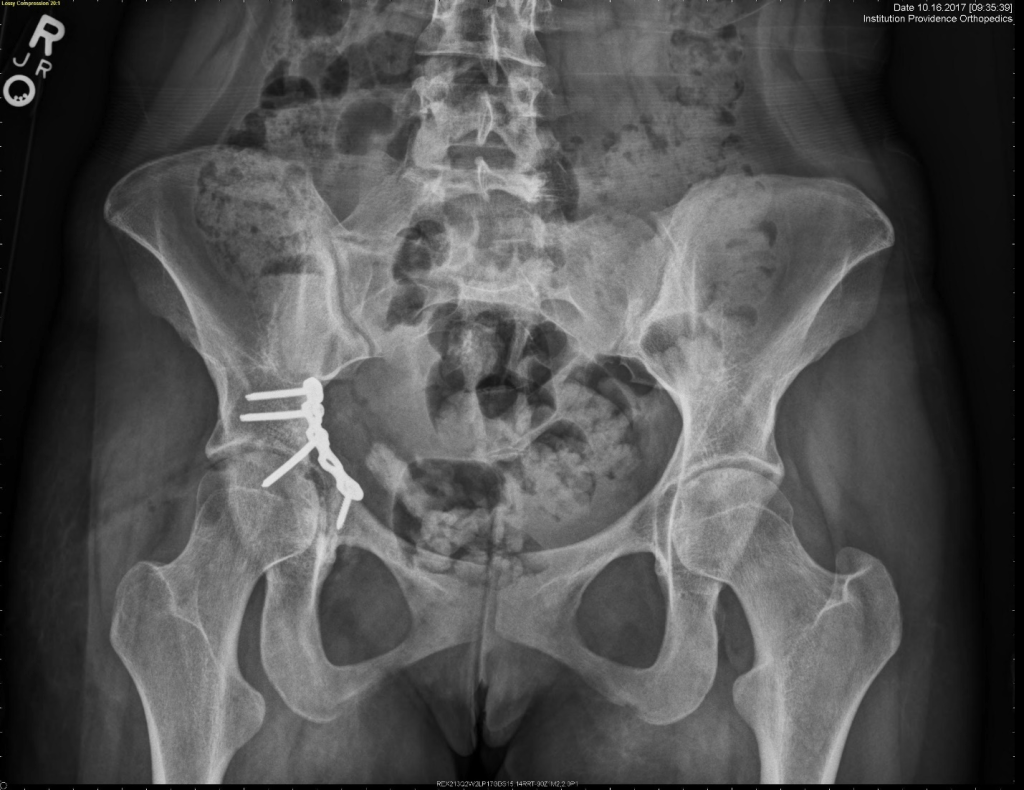

The athlete’s initial imaging was four months before her freshman year of the collegiate volleyball season. Multi-planar single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was performed and the radiologist discovered a 4.8 x 2.4 x 4.2cm lesion in the medial right acetabulum, with internal high attenuation foci suggestive of calcium or chondroid matrix with abnormally increased radiotracer uptake. The lesion had completely eroded through the acetabulum, leaving the patient at risk for pathologic fracture (Figure 1). The athlete had a drill biopsy performed, as well as two open biopsies. The biopsy results proved inconclusive until the second open biopsy confirmed the diagnosis, and the tumor was labeled as benign. She underwent a resection and open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) to remove the osteoblastoma from her acetabulum. This procedure placed a titanium plate and five screws into her pelvis (Figure 2). The surgical site became infected with S. aureus two weeks later leading to an incision and drainage of the infection. She was prescribed Oxycodone, Ondansetron (Zofran/anti-nausea), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (Bactrim), as well as doxycycline (Vibramycin) and enoxaparin 40 mg/0.4 mL injection (Lovenox) to treat pain and fight the infection for two weeks.

From the first biopsy until the surgical resection, the athlete was on crutches and was partial weight-bearing. Following the resection, she was completely non-weight-bearing for two weeks to minimize the load on the plate and screws in her pelvis. After those two weeks, she was partial weight-bearing. At 4-weeks, pelvic X-rays were taken, and the subject progressed to weight-bearing as tolerated. Initially, her physical therapist advised she perform light hip/pelvis stretching and passive ROM exercises. Athletic trainers assumed oversight of her rehabilitation upon arrival at college. Her rehabilitation protocol was guided largely by existing protocols from hip labral repair and ACL-reconstruction focusing on strengthening the hip, hamstrings, and core. The athlete’s criteria to return-to-play (RTP), as established by her physician, included full practice sessions performed at 100% effort without symptom provocation. She has successfully returned to play 2-years out from her surgical resection and ORIF.

The athlete’s primary care provider believed she was suffering a stress fracture in the low back, so further imaging was requested. Her physician indicated that she suffered of low back pain and radicular pain into her right hip for 1.5 years and the pain had progressively worsened over 3.5 months. Following SPECT imaging, the radiologist found an assimilation joint on the right at S1-S2 with mildly increased radiotracer uptake, compatible with Bertolotti’s syndrome. Following the second open biopsy, the cytologist stated that the lesion appeared to represent an osteoblastic lesion with atypia and at least focally aggressive features, leading to the final diagnosis of an aggressive osteoblastoma of the acetabulum. Differential diagnoses included osteosarcoma, aggressive osteoblastoma, and less likely, clear cell chondrosarcoma.

Discussion

Hip pain in the young adult is non-specific and can be due to sports-related or non-sports related conditions (10). Pain is commonly caused by overuse or stress injury, acute injury, or sports-related activity exacerbated by a congenital predisposition (10). Due to the non-specific clinical features and low prevalence, the diagnosis of an osteoblastoma is often missed or delayed (14). As a rare cause of hip pain in a young adult athlete, this case of an aggressive osteoblastoma of the acetabulum provides clinicians a differential diagnosis if conservative treatment fails.

The challenge for the clinician is to apply the knowledge from the literature that describes regional hip problems to clearly identify the anatomical structure and pathological process that requires immediate treatment or referral (10). The athlete’s chief complaint was a chronic deep, aching pain from her outer hip to upper groin. From this pain description, the clinician should know that a complaint of groin pain often has an intra-articular etiology, whereas lateral hip pain is usually associated with an extra-articular etiology (7). In general, a pain that is deep, aching and non-specific is likely to be joint in nature (10). However, localization of hip pain may be difficult, as it may be felt in several different areas simultaneously (10).

The clinician must ask about the mechanism of injury, whether it be acute or chronic in nature. Initially, the athlete complained of pain only once every three months, eventually progressing to every day. An osteoblastoma often presents with a gradual onset of worsening symptoms that may or may not affect athletic performance. These circumstances should prompt the clinician to seek further evaluation (10). The typical presentation of an osteoblastoma is hip pain that is relieved with administration of analgesics like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (5, 12). Clinicians should be wary of red flags such as excessive use of NSAIDs for worsening symptoms.

The various combinations of special tests of the hip challenge the clinician to choose those that provide the most clinically relevant information (7). Based on subjective and objective assessments, the clinician may refer the patient for imaging to confirm a diagnosis, determine the extent of damage, and guide treatment and rehabilitation (10). The radiographic examination should include a plain radiograph, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (6). For the detection of osteoblastomas, CT appears to be a more valuable imaging tool than MRI because it can clearly demonstrate tumor size, location, central calcification within the lesion, and delineate the cortical destruction or soft-tissue extension (14).

For Stage 1 and 2 lesions, the recommended treatment procedure is extensive intra-lesioned curettage and packing of the defect with a bone graft (5,9). For Stage 3 lesions, wide resection is performed. Such excisions are usually curative for osteoblastomas (5). Resection of sub-chondral lesions requires removal of the overlying cartilage and is not feasible in lesions in the major weight bearing areas of the acetabulum or femoral head (3). The subject’s osteoblastoma was classified as aggressive in the acetabulum of the hip, a major weight-bearing area, and surgeons found this case to be a surgical dilemma. The surgeon ultimately decided on performing a surgical resection and ORIF.

There is no specific rehabilitation protocol for patients recovering from a surgical resection and ORIF for an osteoblastoma of the acetabulum. The most similar pathology with documented RTP outcomes is that of an acetabular fracture. Fractures of the acetabulum are most common in young, active people and are known to be associated with a high degree of disability and poor functional outcomes due to the variable degree of involvement of the hip joint(4). In a study with patients who underwent internal fixation for an isolated acetabular fracture, there was a significant reduction in the level of activity and frequency of sport (6). Nevertheless, 42% were able to return to their previous level of activities, and 67% were able to participate in sport at some level (4).

Throughout the treatment and recovery process, it is vital that clinicians understand the relationship between mental and physical health to support their patients who suffer a rare, complicated pathology like an osteoblastoma. With early complications, like S. aureus infection, the athlete may experience frustration and fear that they may not overcome these obstacles to progress in her rehabilitation. To promote overall well-being, the clinician should actively engage in short- and long-term goal-setting with the patient and encourage proper self-care of the patient (1).

To optimize post-surgical outcomes, it is vital for clinicians to practice cross collaboration with other members of the multidisciplinary team. The assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and recovery of a pathology with non-specific features really challenges a healthcare team’s teamwork requiring commitment and focus on developing an individualized plan of care to accomplish the patient’s short- and long-term goals (8). The development of specific goals involves honest and constant communication among the patient and involved healthcare providers (8). Returning to play may be the athlete’s primary goal, but there is life beyond sport, and it is up to the multidisciplinary team to discuss the athlete’s future goals and aspirations, and strive to achieve these.

The athlete’s RTP is yet to be determined considering there is little research regarding the RTP following a surgical resection and ORIF of an osteoblastoma in the acetabulum. However, a recent case study of an 18-year-old multi-sport female athlete with an osteoblastoma in the lumbosacral region revealed that the patient returned and remained active in sports following her tumor excision and sacral hemi laminectomy (2).The timeline in which the subject returned to play was not specified, but the case represents a successful return-to-play outcome of an athlete suffering of an osteoblastoma.

Conclusion

An aggressive osteoblastoma of the acetabulum of the hip is extremely rare but is important to consider as a differential diagnosis of chronic hip pain. Information should be gathered regarding sports participation, time spent training versus time resting, the location, quality, and duration of pain, as well as the mechanism of injury (2). Although current literature is lacking in return-to-play outcomes following a resection of an aggressive osteoblastoma, the clinician is responsible for developing a multidisciplinary individualized plan of care for the athlete. Just as importantly, a cross-collaborative approach to care is vital to the success of the athlete’s return-to-play outcome.

Applications in Sport

This article is written for coaches, athletic trainers, and other sports health related personnel to gain a better understanding of the importance of early diagnosis of an injury as well as working collaboratively to treat an athlete to facilitate return to sport.

Referrences

- Ayers DC, Franklin PD, Ring DC. The Role of Emotional Health in Functional Outcomes After Orthopaedic Surgery: Extending the Biopsychosocial Model to Orthopaedic. AOA Critical Issues. 2013;165:7-13.

- Blauwet C, Borg-Stein J. Osteoblastoma as the Cause of Persistent Lumbosacral Pain in a Female High School Athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11(1):24-27.

- Frank JS, Gambacorta PL, Eisner EA. Hip Pathology in the Adolescent Athlete. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:665-674.

- Giannoudis P V., Nikolaou VS, Kheir E, Mehta S, Stengel D, Roberts CS. Factors Determining Quality of Life and Level of Sporting Activity after Internal Fixation of an Isolated Acetabular Fracture. J Bone Jt Surg – Br Vol. 2009;91-B(10):1354-1359.

- Günel U, Daǧlar B, Günel N. Long-Term Follow-Up of a Hip Joint Osteoblastoma After Intralesional Curettage and Cement Packing: A Case Report. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2013;47(3):218-222.

- Haddad FS. The Young Adult Hip in Sport. Springer-Verlag London. 2014;284-286.

- Marwan YA, Abatzoglou S, Esmaeel AA, et al. Hip Arthroscopy for the Management of Osteoid Osteoma of the Acetabulum: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Case Report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(1):1-7.

- Momsen AM, Rasmussen JO, Nielsen CV, Iversen MD, Lund H. Multidisciplinary Team Care in Rehabilitation: An Overview of Reviews. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(11):901-912.

- Patel S, Agrawal A, Maheshwari R, Chauhan VD. Periosteal Osteoblastoma of the Pelvis: A Rare Case. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;40(1):77-80.

- Pilavaki M, Petsatodis G, Petsatodis E, Cheva A, Palladas P. Imaging of an Unusually Located Aggressive Osteoblastoma of the Pelvis: A Case Report. Hippokratia. 2011;15(1):87-89.

- Sharma A, Gogoi P, Arora R, Haq RU, Dhammi IK, Bhatt S. Aggressive Osteoblastoma of the Acetabulum: A Diagnostic Dilemma. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9:S21-S25.

- Von Chamier G, Holl-Wieden A, Stenzel M, et al. Pitfalls in Diagnostics of Hip Pain: Osteoid Osteoma and Osteoblastoma. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30(3):395-400.

- Weiser MC, Moucha CS. The Current State of Screening and Decolonization for the Prevention of Staphylococcus aureus Surgical Site Infection after Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surgery-American Vol. 2015;97(17):1449-1458.

- Yang CY, Chen CF, Chen WM, et al. Osteoblastoma in the Region of the Hip. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2013;76(2):115-120.