Latest Articles

Outsourced Marketing in NCAA Division I Institutions: The Companies’ Perspective

Submitted by Robert Zullo, Willie Burden, Ming Li

ABSTRACT

Outsourcing is a crucial tool that allows sport organizations to turn over their noncore processes to external service providers. The outsourced service providers help sport organizations focus on sales efforts to maximize revenue. The purpose of this study was to examine outsourced marketing in NCAA Division I institutions from the outsourced marketing companies’ perspective. A survey was conducted to gather information from the general managers at the primary outsourced marketing company’s property affiliated with select schools in NCAA Division I conferences. Collected data were analyzed with descriptive statistics along with qualitative responses. The study found that the outsourced marketing firms focus on revenue generation through securing corporate sponsors. Primary inventories sold included commercials during radio broadcasts of games and signage at athletic facilities. These are typically packaged with the sports of football and/or men’s basketball. The study found that many sponsorship categories remained unfulfilled. There was also growing concern by the companies regarding the escalading financial guarantees paid to the schools. The findings and recommendations are valuable to college administrators, athletic directors and outsourced marketing firms as the parties strive to find outcomes beneficial to everyone involved in the partnership.

INTRODUCTION

More and more collegiate athletic departments have adopted outsourcing as a strategy which uses their corporate partners, such as State Farm, Burger King or Verizon Wireless, to help them earn additional revenue in exchange for advertising at the sporting events. Outsourcing is a crucial business strategy that allows companies to turn over their noncore processes to external service providers while the company concentrates on its core competencies (18). In the highly competitive environment of intercollegiate athletics, some schools are able to handle its corporate partnerships with in-house marketing departments. However, the growing trend for major NCAA Division I schools is to outsource its marketing efforts to an outsourced marketing company that specializes in the sales of inventory such as commercials on radio broadcasts or coaches’ television show, corporate hospitality at home sporting events, signage at athletic facilities and more (24, 38).

The athletic department will typically sit down and outline what they would like to see from an outsourced partner (2). For most schools, outsourced companies offer the opportunity to streamline operations or provide resources that might not otherwise exist, such as sales expertise (24). Li and Burden (24) add that the athletic department may want a company to produce radio call-in shows or coaches’ television shows in addition to the sales efforts. The outsourced companies would have a greater opportunity to improve the quality of the broadcast and simplify the production efforts.

Host Communications, International Sports Properties (ISP Sports) and Learfield Communications were viewed as the main outsourced marketing companies in the early 2000’s (38). Nelligan Sports was also seen as an emerging outsourced marketing company. These outsourced companies handle sponsorship sales while the in-house marketing department shifted its attention to promotions and increasing attendance and ticket sales. The outsourced company would maintain a “property” at the school with the property serving as an extension of the parent company. The property was responsible for the sales efforts and reporting back to the parent company.

The benefits of the outsourced marketing partnership are that of guaranteed and additional revenue (19). An outsourced marketing company will promise a financial guarantee of a set amount to the school’s athletic department in exchange for being able to sell the “rights” of that athletic department. Another option includes a simple revenue-sharing model for the “rights.” The rights could be in the form of a radio commercial, an on-field promotion, a giveaway at a sporting event, or signage at an athletic facility including on a video board (38).

To a lesser extent, the outsourced company will also sell advertising in game programs, on ticket backs and on the athletic department’s website. A fan might pick up a schedule poster and schedule card at a football game with a sponsor’s logo on it. That sponsor may also have a permanent sign at the football stadium visible to fans and may also host a corporate village for its clients prior to the game. In exchange for its advertising opportunities, the sponsor will pay the outsourced marketing company an agreed upon amount of money. The outsourced marketing company will then put that revenue towards the promised guarantee for the athletic department. Once the guarantee is met, the athletic department receives an agreed upon percentage of any future revenue, but it is there that the outsourced company earns its greatest financial sales commission. If this financial model is not used the straight revenue sharing of each sponsorship sold is another viable option.

As these outsourced marketing companies gain more schools under their watch, they spread their sales territory and can start to package a few schools with one corporate sponsor. For example, ISP Sports may approach Verizon about a national sponsorship deal that could reach the Northeast through sponsoring Syracuse University, the West Coast through sponsoring UCLA, the Midwest through sponsoring the University of Houston and the Southeast through a sponsorship of Georgia Tech Athletics. At the same time, Verizon may also discuss a similar deal with Host Communications through sponsoring the athletic departments at Texas, Boston College, Arizona, Kentucky and the University of Michigan. Companies might also pursue schools in a set geographic region, further enabling them to partner with corporate partners exclusive to that particular region. By strategically acquiring attractive schools (those with large market areas and large fan bases) around the country, the outsourced marketing companies can pool their resources, reduce their costs and diversify their portfolio of schools at the same time.

A number of studies have examined the perceptions of athletic directors and senior staff administrators from the institutions that partner with an outsourced company about their relationship with their outsourcing partners (10, 19, 24, 25, 38). Issues examined include details of the outsourcing contracts such as the length of the term, the financial guarantee, and the strengths and weaknesses of the outsourced partnership. This current study provided the outsourced company a chance to respond with its own sentiments about the relationship and future issues related to outsourced marketing. An analysis of the schools’ responses in conjunction with the responses of the outsourced marketing companies could help make for a better relationship in the future. The purpose of this study was to examine outsourced marketing in NCAA Division I institutions from the outsourced marketing companies’ perspective.

An Overview of Outsourced Marketing in Intercollegiate Athletics

The most significant outsourced marketing deal to date took place early in the fall of 2004 as Host Communications won the rights to the University of Kentucky athletics in a ten-year deal valued at more than $80 million. Host placed a bid of $80.475 million edging the bid of $80.35 million submitted by Learfield Communications, while ESPN Regional bid $74 million and Viacom Sports $55.25 (29). The previous deal was $17.65 million over the course of five years and expired April 15, 2005 (20). This deal established a benchmark that has since been surpassed, but clearly raised the fair market value.

To look at the origin of outsourced companies’ involvement with athletic departments, it is necessary to start in Lexington, Kentucky, and the origin of Host Communications. In 1973, Jim Host bid on the rights for the University of Kentucky in what is the first believed outsourced deal in intercollegiate athletics. Within ten years, Host had secured the rights to the Final Four after convincing then NCAA president Walter Byers that corporate marketing was the wave of the future (34). Host saw the opportunity that existed in advertising and licensing given the affinity associated with the college sports fan.

In working with colleges and universities and their marketing efforts, what Host strived for was a clean venue comparable to the Olympic Games where there was limited signage and less clutter in the advertising. The corporate partners who paid the most would receive these exclusive opportunities to advertise. Host notes that the philosophy is not applied to the Bowl Championship Series which is run outside the control of the NCAA (34).

Today, Jim Host is no longer head of the company he started, but he has enjoyed seeing the company grow to the point that it sells advertising on over 500 radio stations for the Final Four (5). This is up from the 200 radio stations the company partnered with in 1982 (12). Host also prints game programs for over 43 NCAA championships and operates most marketing and promotional aspects of the NCAA events. It annually earns over $100 million in revenue (7) and has not limited itself to just intercollegiate athletics. Event marketing in junctures as diverse as Streetball and the National Tour Association (tourism industry) have led the company to be recognized by the SportsBusiness Journal as one of the top five marketing companies in the world and the premier in intercollegiate athletics (6). In 2007, global sports marketing giant IMG purchased Host Communication, as the company exists today as IMG College (17).

In time, other companies began to surface to challenge Host Communications as the “one-stop” shopping point for colleges and universities. The companies realized what athletic departments were failing to grasp, that season-ticket holders were more than just fans who wrote a check once a year for seats to a sporting event. These fans were consumers that could spend up to $100,000 or more during a lifetime on tickets, concessions, and parking (22). In addition, the fans were loyal to their teams and everything associated with their team.

Corporate partners began to realize this and wanted to partner with schools. With money to be made and Jim Host demonstrating some early financial return on investment for the University of Kentucky, more start-up outsourcing companies wanted to become involved in their revenue opportunity. Some of the companies were locally owned and operated, but others were more regional like an ISP Sports, Learfield Communications, or Nelligan Sports. Companies and athletic departments sat down to best figure out which schools were good fits for which company and how to best utilize the relationships over the long-term. After that outsourced companies began to provide sponsorship options or packages to corporate sponsors based on what other schools were doing (22).

In creating packages of what could be sold, the typical items included signage at the athletic facilities, television rights and radio broadcast rights (14). Cohen adds that higher dollar values were attached to such sponsorship packages and enabled athletic departments to offset growing expenses including scholarships and rising facility costs. Schools would “bundle” their inventory and see more of the revenue return directly to the school instead of multiple outside parties (13). Outsourced marketing enabled corporate sponsors to visit one individual or company instead of stopping at the radio station to gain radio advertising during game broadcasts, stopping at the local television station to gain on-air advertising during coaches’ television shows, then concluding with a visit to the athletic department for additional advertising signage at the athletic facilities. This is especially true as video boards became more and more detailed in intercollegiate athletic facilities starting with the University of Nebraska in 1994 (31).

As scoreboards have been supplemented or replaced with video boards fans are now afforded instant replays and advertising messages. A full-color video board could now offer “fan of the game” or “play of the game” or “great moments in history” segments that are presented in collaboration with a corporate sponsor. It could also roll a commercial exactly like the ones seen on television at home. Steinbach (31) noted that with their addition of video boards, Michigan State experienced a sponsorship revenue increase from $400,000 in the pre-video days in 1998 to more than $3 million annually by 2002.

While these video board improvements provided new fan entertainment and sponsorship revenue, they did not come without a price. Many older fans thought the video board was too much like the television they chose to leave at home. Others felt the noise was too distracting and took away from the natural elements of the sporting event including the fans’ cheering, the band and cheerleaders (15). Athletic administrators and outsourced companies had to evolve to package their advertising in subtle fashion around trivia contests, historic moments, replays and scores from around the country. Pure video commercials advertising products were not welcomed in the stadium as it distracted from the entertainment aspect of the game itself. Furthermore, sponsors recognized that if fans were not happy with the advertising, their affinity to the sponsor would not be positive either. Too much advertising could also lead to a clutter of sponsors with their advertising messages being lost on the fans (15). The message was heard by the outsourced companies which now included Viacom Sport and Action Sports Media in the mix.

Recent Concerns in Outsourced Marketing

Arizona State University completed a study in 2004 on a small sample size that found that in intercollegiate athletics, sponsorships are typically formed in the categories of: airlines, auto parts, beer, credit cards, DSL, gas/oil, health and fitness, long distance, paging devices, and tires/auto services (3). The same group also found that categories frequently ignored include: auto parts, boats/marines, computer hardware/software, delivery services, department stores, drug stores, electronics, hardware/home improvement, music stores, pharmaceuticals, personal hygiene, video game systems and video stores. One major concern is that ignoring these categories can result in significant lost revenue. Tim Hofferth, president and chief operating officer of Nelligan sports stresses that outsourced companies cannot ignore pre-existing business relationships between schools and area businesses as those are additional sponsorship opportunities waiting to happen (23). This is particularly important as the parent outsourcing companies, with a greater portfolio of schools, pursue national sponsorships that are more financially viable to the parent company relative to the schools’ properties pursuing regional and local sponsorships. Therefore another concern is that local relationships can be impaired or even lost.

Additional research by Walker (36) noted that it is important that communication between the outsourcing property and the school remain a high priority. Because of the athletic department’s affiliation with an institution of higher education there are certain restrictions that exist that may not be as prevalent in professional sports. Such restrictions may central on alcohol, gambling or lottery sponsorships or trying to maintain a “clean” image at the sporting events to avoid concerns of excess commercialization within higher education. Goals, philosophy and objectives between the school and property must be aligned (11).

Future research needs to also explore whether the escalating guarantees paid to schools have grown too rapidly for the outsourcing companies to keep pace. After Kentucky signed their landmark deal, Connecticut, Arizona, Tennessee, Alabama, Michigan, Texas, North Carolina, Florida, Ohio State and Nebraska have since signed contracts guaranteeing at least $80 million to their schools from their respective firms (29). Wisconsin, Oklahoma, LSU and Arkansas are all guaranteed at least $73 million through their school’s contractual obligations with outsourced marketing firms.

Outsourcing as a Strategic Alliance: A Brief Overview

As competition becomes more and more intensified, individual firms have to seek out strategies to stay competitive. One of such strategies is strategic alliances (16). The age of in-house operations is quickly being replaced by the age of alliances (16).

According to Spekman and Isabella (30), an alliance is a close, collaborative relationship created between two or more firms for the sake of accomplishing some goals that would be difficult for each to accomplish alone. By collaborating, alliance partners will not act in self-interest, but will promote the partnership and foster its strengths. There are several benefits of forming a strategic alliance. According to Parise and Casher (26), a strategic alliance is characterized as “an open-ended agreement between two or more organizations which enables cooperation and sharing of resources for mutual benefits, as well as enhancement of competitive positioning of all organizations in the alliance” (p. 26).

1. Strategic alliances exist to create value. Whether or not it is in the form of new market penetration, increased profit sharing, or competitive opportunities, companies join to reap the benefits that neither partner could enjoy alone.

2. Strategic alliances are developed to create a number of advantages. Some of these advantages are opportunity-based alternatives. In other words, strategic alliances can provide firms in the alliance with many opportunities to reposition themselves in the market because the infrastructure network created by the alliance gives all members access to a range of information, markets, technologies, and ideas that would be far beyond their reach otherwise (16, 27). Due to the fact that it is often difficult for a particular firm to possess all the resources required to meet new challenges and opportunities, the formation of an alliance can be extremely advantageous (16).

3. Strategic alliances are developed to divert corporate attention away from nonessential efforts where the firm lacks expertise, cost advantage, or scale. The skills gained through new partnerships can introduce new techniques, market segments, or new geographic markets, and the addition of complementary skills also helps boost revenue opportunities by gaining greater returns from existing customers, channels, and products (1, 30).

Outsourcing within intercollegiate athletics is a viable means for an athletic department to utilize strategic alliances to create value and take advantages of skills that may not be found with the in-house marketing staff. The outsourced marketing firm can focus on revenue generation while the in-house marketing staff enhances event atmosphere and boosting attendance.

METHODS

Subjects

The general manager at the primary outsourced marketing company’s property affiliated with select schools in NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision conferences was the original subject of this study. The select NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision conferences included such six conferences as the Atlantic Coast Conference (12 schools), Big East Conference (12 schools, including four independents), Big Ten Conference (11 schools), Big Twelve Conference (12 schools), Pacific Ten Conference (10 schools), and Southeastern Conference (12 schools). Each of these six conferences is a member of the Bowl Championship Series, the leader in the Football Bowl Subdivision, formerly Division I-A, post-season play. Furthermore, earlier research by Zullo has indicated that a majority of schools outside of these six selected conferences affiliated with the Bowl Championship Series do not have an existing relationship with an outsourced marketing group (19).

With the six BCS conferences, there are a total of 69 schools. Among these 69 schools, 13 handle their marketing in-house and an additional seven were marketing in-house and recently reached an agreement to start a relationship with an outsourced marketing partner (19). That left 49 schools with outsourced marketing relationships. However, seven schools used multiple companies in their outsourced marketing efforts rather than pooling their efforts bringing the number of included participants down to 42. For example, one firm may sell signage at the stadium while a second sells radio inventory. These schools were not included as this research focused on school’s exclusive outsourcing partnerships only.

The main outsourced parent companies include ESPN Regional, Host Communications (presently called IMG College), International Sports Properties (ISP Sports), Learfield Communications, Action Sports Media, Nelligan Sports, and Viacom Sports (presently called CBS Collegiate Sports Properties). An examination of these companies found an additional 19 Division I schools with outsourced marketing relationships. These 19 schools are not in the six major conferences but have been included in the study to increase the sample size to 61.

Instrumentation

To achieve the objectives of this study, a questionnaire was designed and utilized to examine the outsourced marketing companies’ perspective pertaining to their affiliations with NCAA Division I institutions. The researcher designed the questionnaire in consultation with four account executives from two major sports marketing firms. These four reviewers were not general managers with the outsourced marketing properties thus they could freely express their suggestions and concerns. This collaboration enabled further critique, expertise and anonymous feedback to enhance the instrument’s validity. Further review by academic colleagues aided in the process of eliminating biased questions or clarifying wording. The questionnaire and consent form were then sent to the general managers of the outsourced marketing companies’ operations at 61 major NCAA Division I institutions.

Both close-ended and open-ended questions were included in the survey instrument. There were nine open-ended questions. They were (a) what is the property’s best method of soliciting sponsors? (b) what are the primary goals of outsourced companies? (c) how often do outsourced companies fail to meet their financial guarantee to their schools? (d) what inventory sells the most, the least and why? (e) what sponsorship categories are presently being sold and which are ignored in sales? (f) why do outsourced companies sell certain sports and not others? (g) what are the strengths and weaknesses of outsourced marketing companies? (h) what do outsourced marketing companies perceive as the future problems with outsourced marketing? and (i) at what level is outsourced marketing a good fit within college athletics?

Data Collection and Analysis

The survey instrument was mailed to the respective general managers with a second mailing added to heighten the response rate. Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies were used to analyze the collected data. Qualitative responses were also analyzed to identify reoccurring themes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As mentioned previously, the purpose of this study was to examine outsourced marketing in NCAA Division I institutions from the outsourced marketing companies’ perspective. Twenty-eight general managers of the identified sixty-one NCAA Division I institutions responded to the survey, which accounted for a 46% response rate.

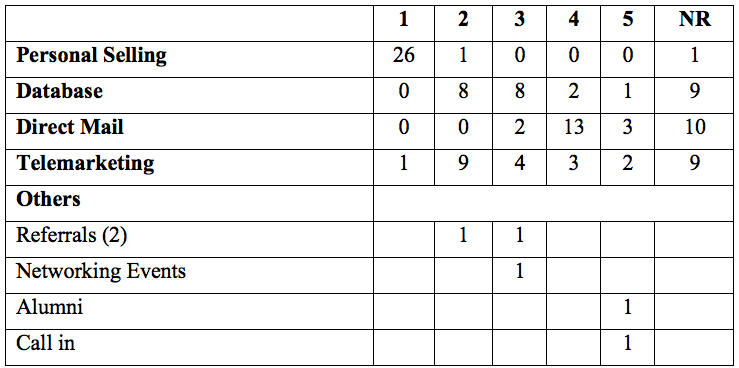

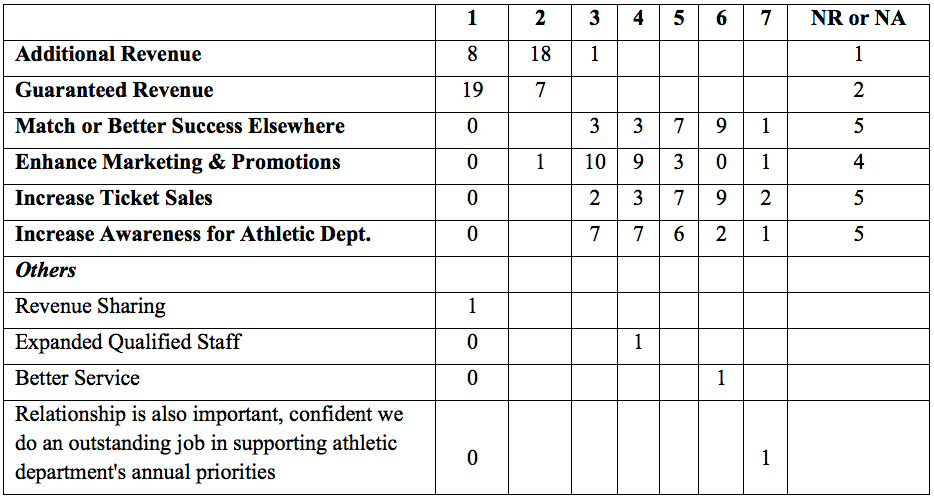

Primary Goals of Outsourcing Marketing Operations

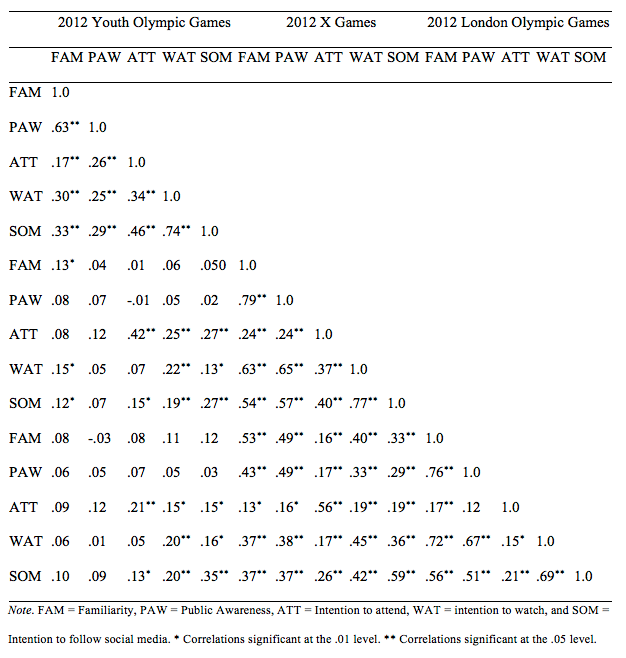

In conducting their sales efforts, most surveyed properties (93%) focus on personal selling efforts as their means of reaching out to potential partners or sponsors. Telemarketing and using a database are secondary methods of soliciting sponsors or partners. These sponsorships or partnerships are secured for the primary purpose (68%) of generating revenue for the overall parent company to meet the guarantee to the school. After that goal is met then the secondary focus becomes trying to bring in additional revenue beyond that initial guarantee. This is consistent with previous literature by Burden and Li (9-10) and Zullo (38). The findings are also congruent with the strategic alliance research that place an emphasis on the value of partnerships yielding enhance values to both parties (26).

Table 1 Property’s Best Method of Soliciting Sponsors/Partners/Clients

Table 2 Primary Goals of Outsourced Marketing Properties

As mentioned earlier, this revenue is ultimately shared with the affiliated institution of higher education’s athletic department. It should be noted that the surveyed general managers indicated that outsourced properties focus on sales and not on the business of enhancing an athletic department’s marketing or promotional efforts. The outsourced properties responding also did not indicate a willingness to boost ticket sales or create awareness for the athletic department. This is also in line with past research by Zullo (38) and Burden and Li (9). Consistent with research in strategic alliance the in-house marketing departments focus on the areas of ticketing and brand awareness while the outsourced firms avoid such areas where they lack expertise and experience (1, 18, 30)

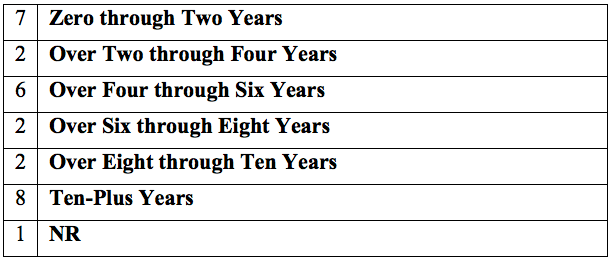

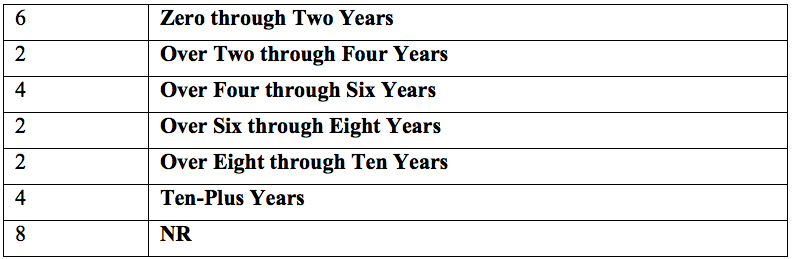

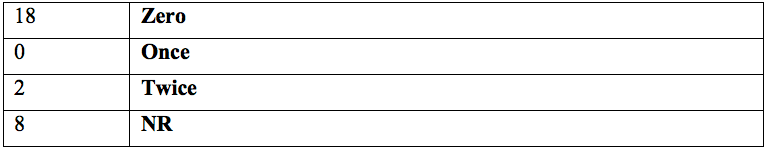

Duration of Relationship and Success Rates

Of the outsourced properties responding, 42% have been working with their current school for over six years and 54% have worked with their school for less than six years. There was one non-response. Twenty of the twenty-eight properties have successfully met their financial guarantee to the school’s athletic department throughout the duration of the relationship with the remaining eight respondents choosing to not answer the question. Of those eight, the subsequent question found that two of them have failed at least once to meet its financial obligation to the school’s athletic department. That is collectively a success rate of greater than 90% for the outsourced marketing properties in meeting their financial guarantees to the schools.

Table 3 Number of Years Property Has Worked With School

Table 4 Number of Years Property has Successfully Met Financial Guarantee

Table 5 Number of Years Property has Failed to Meet Financial Guarantee

If one tallied the cumulative number of years that all of the respondents have partnered with their respective outsourced marketing firms, factoring in the two years the guarantee was not met, that pooled annual success rate improves further thus supporting the philosophy of such alliances as advantageous (16, 30). Why companies failed to meet their guarantee could be asked on further questionnaires to help facilitate what factors impact not meeting the guarantee. Additional questions could also explore whether the escalade in financial guarantees paid to the schools by the properties has hindered the success rate. Furthermore, questions could also ask whether joint bids have become a necessity with the higher paid guarantees. ISP Sports pursued joint bids with IMG College before the latter company acquired the former in 2010 (4).

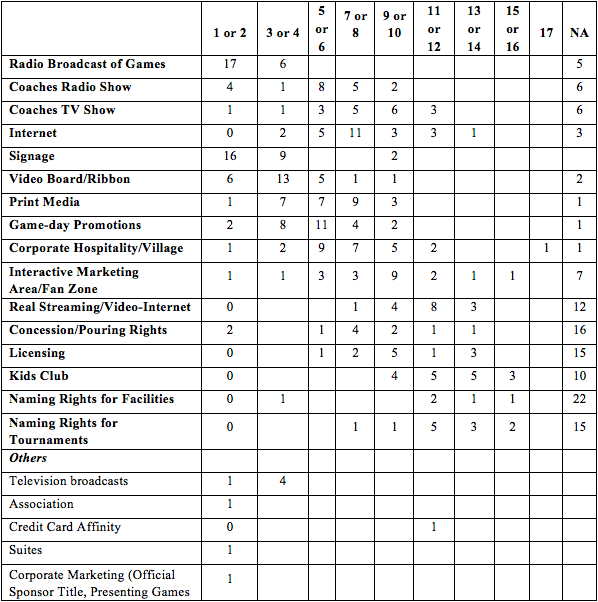

Attractiveness of Marketing Inventory

In examining what inventory items are sold most by the outsourced properties, the respondents cited radio broadcast of games (61%) and permanent signage (57%) at athletic facilities as the best selling inventory. These findings are consistent with Cohen’s findings (13-14) and Zullo’s research in 2000 (38). Video board advertising and ribbon signage at athletic facilities are other top sellers on the second tier of inventory, along with game day promotions and print media. Steinbach noted (31) that while start-up expenses for video boards may be higher the boards can offer a significant return investment. A third tier of inventory would consist of coaches’ radio shows, coaches’ TV shows, corporate hospitality, and the athletic department’s internet advertising rights.

Table 6 Best Selling Inventory Items

The idea of an interactive marketing area or fan zone that is increasingly being found at professional sporting events has not caught on as a popular inventory item at the college level yet. This may be due to the greater expense of such a project relative to the production of a radio commercial or one time cost of making a sign to display in an arena or stadium. An interactive area or fan zone’s costs and expenses could offer a lower financial return on investment for the outsourced marketing property.

The findings indicate that inventory provided by the athletic department and sold by the outsourced marketing company is limited. As professional sports are quick to sell more creative inventory, including corporate hospitality, ribbon stripe advertising in arenas and more fan friendly websites, institutions of higher education, athletic departments and outsourced marketing companies appear to continue to do business in the same way over the last decade as shared by Zullo’s (38) research. Athletic departments that prefer the permanent signage route over ribbon advertising or video board are not maximizing their revenue opportunities. Though accompanied by greater start-up costs, the ribbon advertising and video board messages garner greater fan interest and can be sold at a higher rate to the corporate sponsors. Outsourced companies may provide greater access to this newer technology enabling schools to add inventory they could not otherwise do on their own thus demonstrating another value of the strategic alliance (16, 27).

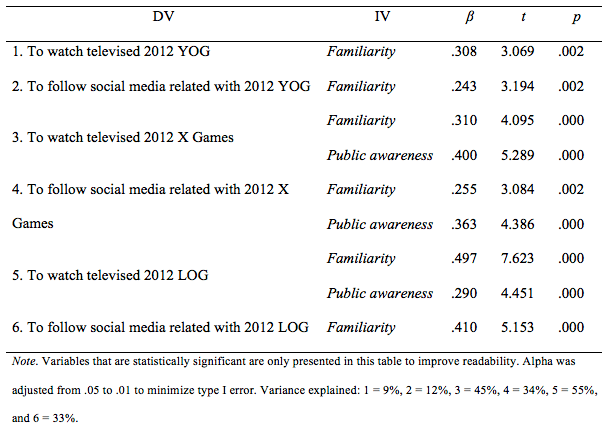

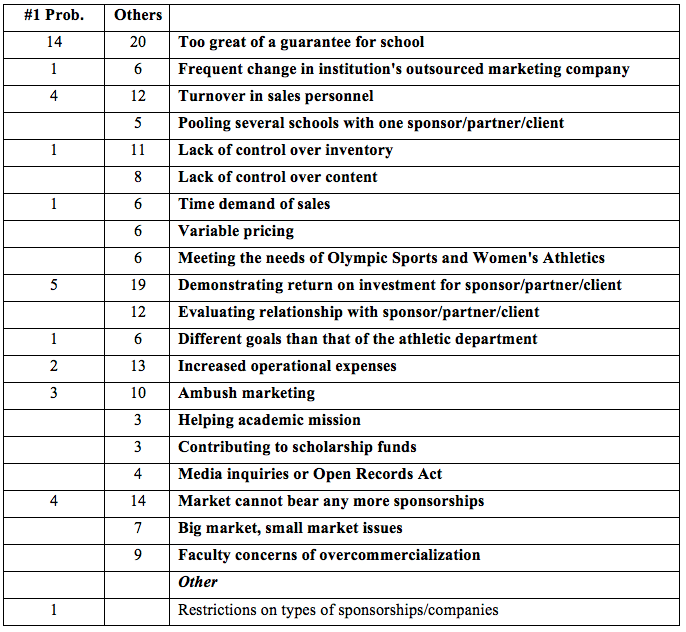

Category Fulfillment

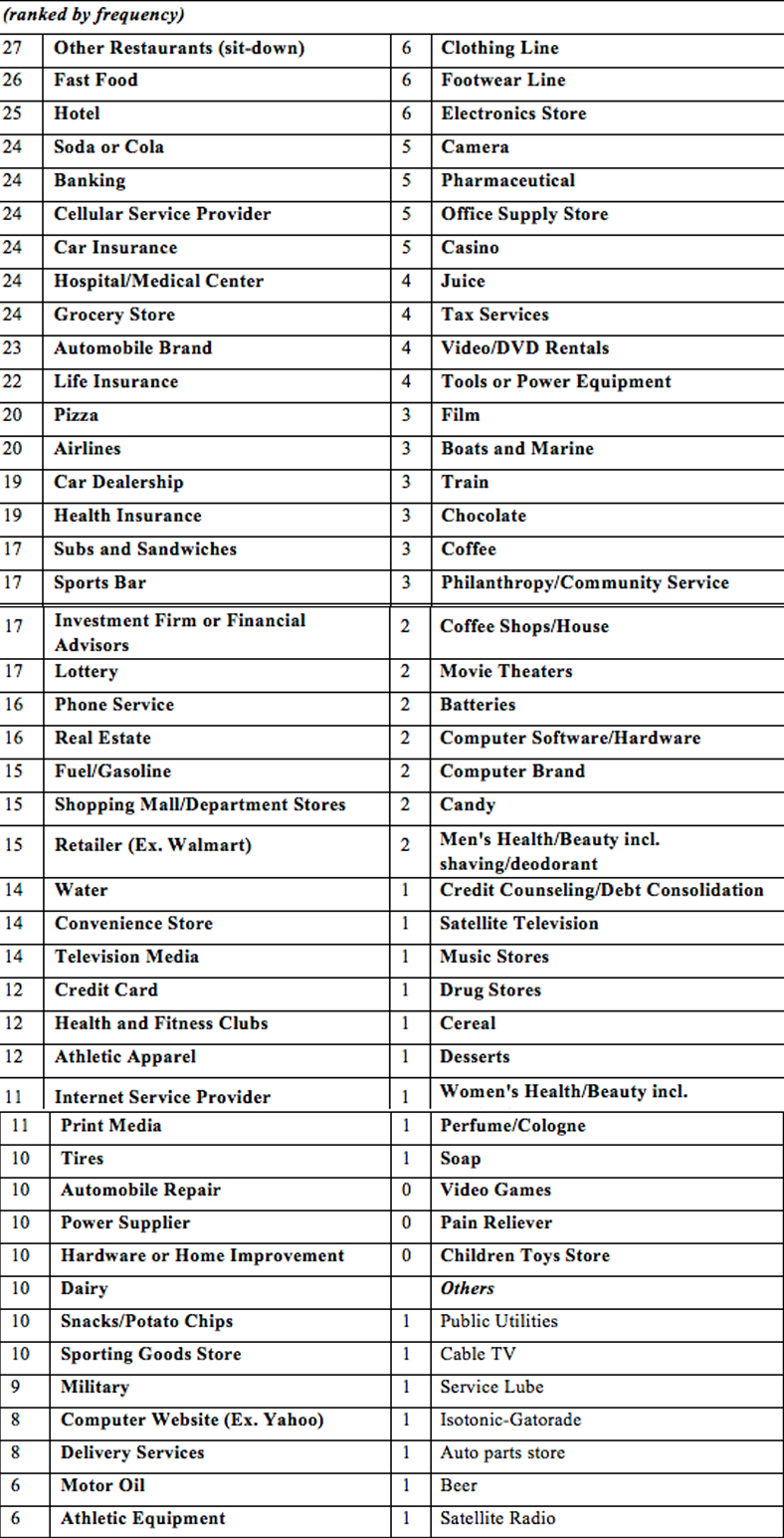

In terms of which sponsorship categories have been filled by the outsourced marketing property in the last three years, 71% of the respondents maintained some form of sponsorship in the categories of sit-down restaurants, fast food, hotel, soda/cola, banking, cellular service provider, car insurance, hospital/medical center, grocery store, automobile brand, life insurance, pizza and airlines. What is notable is the wide range of categories left unfulfilled by outsourced marketing properties including: water, health clubs, credit cards, real estate, tires, military, home improvement, dairy, automotive repair, motor oil, office supply store, tools/power equipment, coffee, satellite television, batteries, delivery services, boats/marinas, and candy. These findings are consistent with the study conducted at Arizona State (3).

Table 7 Sponsorship Categories Successfully Filled in Last Three Years

There are many categories typically sold in professional sport that are ignored in intercollegiate athletics. Future research is needed to address why this is the case. Is the sponsorship not a good fit for the college setting? Have companies tried approaching these categories and failed in their sales efforts? Or are companies aware that a greater financial return can be found with select categories relative to others? Additional research is warranted in this area as strategic alliances may yield new revenue opportunities and open new markets (1, 30), but only as these questions are explored further.

Attractiveness of Sports as Outsourcing Inventories

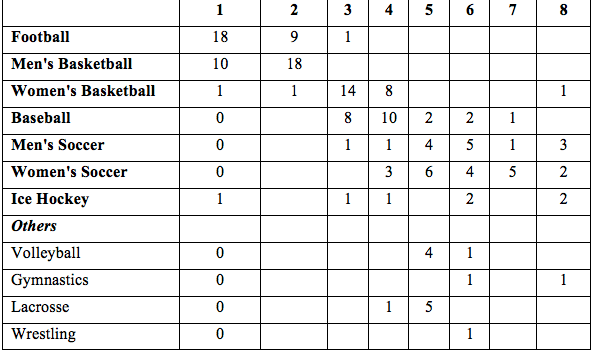

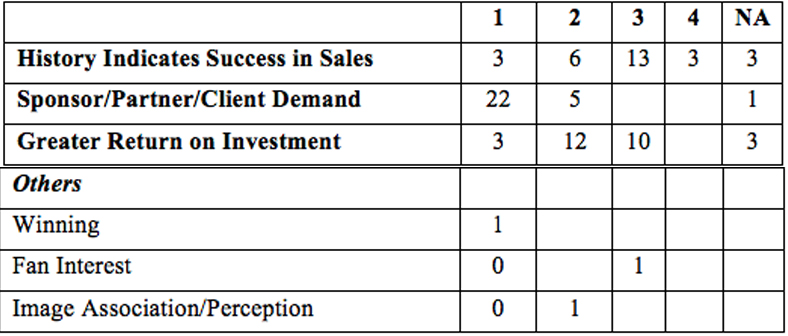

When surveyed general managers were asked what sports sold well when working with corporate sponsors or partners, the overwhelming response indicated football first and men’s basketball second. Women’s basketball and baseball were second tier sports in the sales effort. However, football and men’s basketball sold the best because that is what the sponsor/partner demanded (79%) in the sponsorship package first and it was demanded based on the historical perception of greatest return on investment value.

Table 8 Top Three Sports Outsourced Properties Sell

Table 9 Reasons for Selling Such Sports

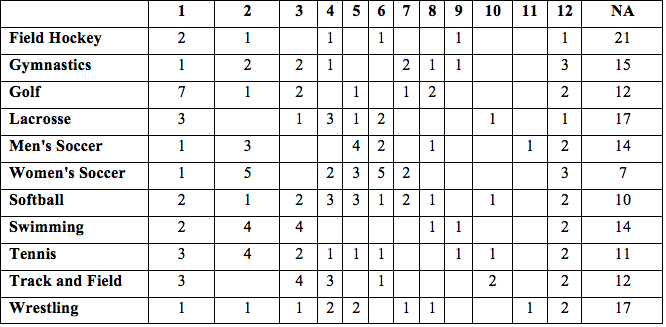

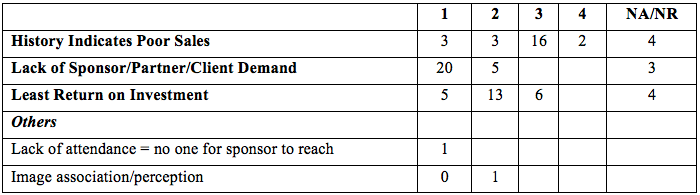

Other sports simply did not garner the sponsor’s interest (71%), offer a significant return on interest (18%), or yield a past history of success in sales (11%). This was especially true of Olympic Sports and women’s athletics excluding women’s basketball. Low regular attendance at Olympic Sporting events equates to low return on investment from the sponsor’s perspective.

Table 10 Top Three Sports Outsourced Properties Did Not Sell

Table 11 Reasons for Not Selling Such Sports

This should not be interpreted as a dislike of these sports, but rather as a financial decision by corporate sponsors. A State Farm or AT&T corporate sponsor has the ability to reach many more fans at a football game then at a tennis match due to the larger attendance of patrons at the football games. Such a sponsor may also have the capability to advertise to a broader audience on the radio and television via the broadcast of the football and men’s basketball games. These findings are consistent with Zullo’s study (38).

Though this may be an area of concern between athletic administrators and outsourced marketing companies, most schools’ administrators understand the financial implications if an outsourced marketing company focuses too much time on selling sponsorships for a softball game instead of football or men’s basketball. The financial guarantee would not be met by the outsourced company and their services would not be retained. While the guarantee would be paid by the property’s parent company, the school would lose confidence in the property’s ability to sell and would look to partner with another company. It is a balancing act by the outsourcing marketing companies and many of these companies have offered to package Olympic Sports or women’s athletics with football and men’s basketball sponsorship packages provided that the corporate sponsor did not object. That noted, schools such as Georgia, Texas, or Stanford may need to explicitly state in their contracts with an outsourcing company that Olympic Sports and women’s athletics must be sold, given the high status of such programs at these schools.

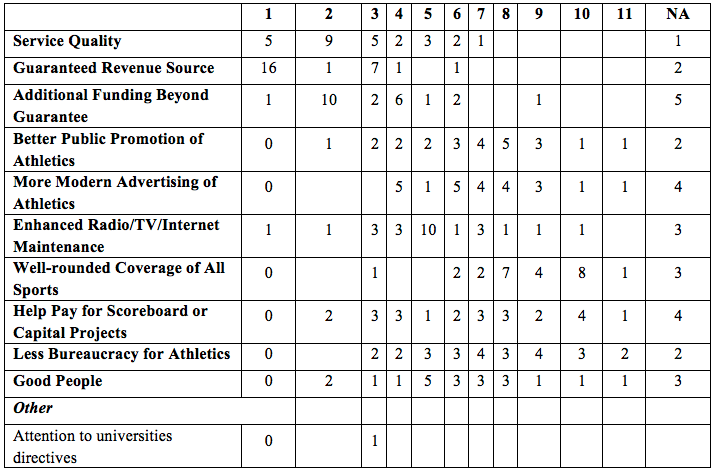

Strengths and Weaknesses of Outsourced Marketing

Respondents noted that the major strength of outsourced marketing properties includes revenue generation (57%) with service quality ranking second. The weaknesses of outsourced marketing properties range from lack of control over content to lack of interest and promotion for certain sports. This reaffirms the previous research of Zullo (38) and Li and Burden (24).

Table 12 The Major Strengths of Outsourced Marketing

Table 13 The Major Weaknesses of Outsourced Marketing

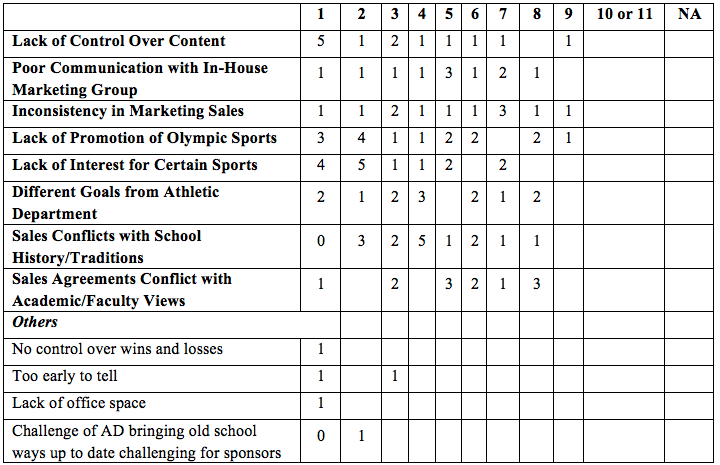

Future Problems/Issues Facing Outsourcing Marketing

The respondents indicated the biggest future problem in outsourced marketing is too great of a financial guarantee for a school (50%), one that an outsourced marketing parent company may have trouble meeting on an annual basis. Smith (29) found that an increasing number of schools were surpassing the 2004 benchmark Kentucky deal as financial guarantees to school were reaching the $100 million mark. Secondary problems include clearly demonstrating a return on investment for sponsors (18%), an oversaturation of the marketplace with sponsorships, and turnover in sales personnel (both 14%). Tertiary concerns include ambush marketing, faculty concerns of over commercialization, increased operational expenses, and lack of control over the inventory and sponsorship content.

Table 14 Biggest Future Problems of Outsourced Marketing

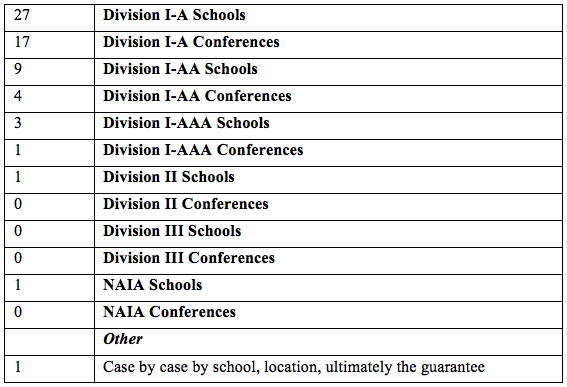

Overwhelmingly, the respondents supported NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision institutions (96%) and conferences (61%) when they were asked the level of intercollegiate athletics outsourced marketing that is best suited for outsourcing. Lower levels of intercollegiate athletics simply did not catch the interest of outsourced marketing properties. Their response is consistent with Tomasini’s (35) findings, as well as those of Zullo (38) and Li and Burden (24). It is hypothesized that this is due to the smaller audience in attendance at sporting events at these levels compared to the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision institutions.

Table 15 Level of Intercollegiate Athletics Outsourced Marketing is Best Suited For

CONCLUSIONS AND APPLICATION IN SPORT

Direct Practical Recommendations

Given the limited amount of research concerning outsourced marketing in intercollegiate athletics, research on outsourcing in higher education in general is important to consider when deciding whether to outsource sports marketing efforts. In examining the findings of this study and turning it into practical applications for presidents, athletic directors and general managers of outsourced marketing companies, the author would suggest the following recommendations for improving the business relationship and being pro-active in addressing future issues in outsourced sports marketing within the context of higher education:

1. Utilizing their acknowledged strengths, outsourced marketing companies should offer their consulting services in the area of marketing and sales to “smaller” Division I schools in non-BCS conferences that would not otherwise be financially attractive to partner with for an extended relationship. Their sales expertise would be considered invaluable to a smaller school and could be an extended revenue stream for the outsourced company collectively. Smaller schools could be packaged by entire conferences, or by several schools in same geographic region, or other characteristic (ex. HBCUs); outsourced companies could sell their season ending tournaments or championships, or “classic” games, etc. Smaller schools should also think in terms of packaging their entire campuses and not just the intercollegiate athletics department. This would help outsourced marketing companies address their concerns with the escalating financial guarantees paid to certain school that reduce the profit margin of the parent company.

2. Outsourced marketing companies must include new categories in their sales efforts as today’s sponsors simply have more places to spend their advertising dollars. Without a clearly defined return on investment, long term corporate partners may consider advertising elsewhere. Before this occurs, outsourced companies need to pro-actively evolve and consider alternative sponsorship categories that have been largely ignored in intercollegiate athletics as demonstrated by the research findings. This can alleviate departing sponsors due to the untapped revenue streams with new categories while also providing support in the escalating financial guarantees owed to schools.

3. In similar fashion, outsourced marketing companies need to continue to expand their inventory options in collaboration with the athletic department. As more options arise for corporate partners to spend their advertising dollars elsewhere, including professional sports, outsourced marketing companies need to be pro-active in offering new and exciting inventory and not remain stuck in the status quo option of radio commercials and permanent signage.

4. Along those lines, athletic departments who think they might not be able to afford new inventory items, particularly video boards and ribbon advertising, need to consider the option of letting an outsourced marketing company buy or finance the technology as they can earn a greater financial return on investment from the corporate partners with new capabilities.

While the arms race in intercollegiate athletics continues to press on and excessive spending in intercollegiate athletics is being criticized by detractors such as the Knight Commission (37), there exists the opportunity for compromise. As administrators in higher education begin to accept this belief as truth, Myles Brand, the former head of the NCAA, insisted that not all external involvement with intercollegiate athletics has been bad be it from alumni, supporters or corporate partners.

Brand (8) stressed that how you utilize the money contributed is of the greatest importance. He stressed that intercollegiate athletics focuses on opportunities for student-athletes namely in the means of scholarships and a quality education. It is not profit-driven like professional sports and owners of the teams. And funding for these scholarships and athletic department operating budgets can derive from corporate partnerships. The key is maintaining a clean fit for the corporate sponsor on the school itself and not just in the athletic setting (21). Outsourced marketing companies can play a vital role in these efforts through collaboration with their school’s mission thereby appeasing such groups as Faculty Athletic Representatives, the American Association of University Professors, the Drake Group, Coalition on Intercollegiate Athletics (COIA), the NCAA and others.

Commercialization is not a bad thing as it occurs all over campus and it frequently comes with initial resistance. Fans and faculty may not initially like the addition of sponsorships, but it does offset the budget for the athletic department without relying too heavily on the university for financial support. As faculty groups arise around the country to denounce athletics’ place in higher education (32-33), it is important to realize that the excessive spending in big-time intercollegiate athletics is the problem and not necessarily the commercialization as that is occurring everywhere on campus.

In examining outsourced marketing companies and their relationship to colleges and universities around the nation, evolutionary and creative thinking needs to occur more frequently. If the outsourced marketing company continues to think from the mindset of the institution of higher education and not purely as a sales group, future relationships will continue to prosper. It is when outsourced marketing companies lose that train of thought that problems start to arise. Ideally, greater communication and utilization of these findings and similar research will enable future relationship between the school, the athletic department and the outsourced marketing company to create a “win-win” situation for all parties involved. In turn, this can also extend over to better benefit the corporate partners for the duration of the partnership.

Limitations and Delimitations of the Study

A number of limitations existed in this study. The willingness of the surveyed general managers to participate and answer the questionnaire honestly, and to share detailed information about their specific marketing contracts and relationship. Another limitation is that some schools may have several outsourced companies overseeing their sales efforts. One company may handle sales for the radio and television while a second company may direct the sales for the athletic department’s signage at athletic facilities. A third may manage the sales for corporate hospitality and promotions. To address this concern, only schools with a single outsourced marketing partner were selected to participate in this study. In-house marketing and multi-sourcing efforts were not addressed.

Finally, as noted above, not all schools in the six major conferences have an outsourced marketing relationship thereby limiting the initial sample size. However, this was offset with the addition of 19 schools that are not in the six major conferences but have existing relationship with the major outsourced marketing companies. All participating respondents shared the characteristics that they are Division I in nature and have an exclusive outsourcing relationship with one of the leading outsourcing sports marketing firms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None

REFERENCES

1. Austin, J. (2000). The Collaboration Challenge: How Nonprofits and Businesses

Succeed Through Strategic Alliances. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

2. Begovich, R. (2002, February/March). Adding an agency. Athletic Management, 14(2). Retrieved February 12, 2005, from http://www.momentummedia.com/articles/am/am1402/agency.htm

3. Bent, D., Rode, C., Rogers, M., & Whitley, R. (2004, August). Corporate sponsorship. Athletics Administration, 10-11.

4. Berkowitz. S. (2010, July 29). IMG buys ISP Sports, gains marketing leverage. USA Today. Retrieved July 29, 2010, from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/college/2010-07- 28-img-buys-isp-sports_N.htm

5. Bernstein, A. (1998, December 21). College sports finds a gracious Host. Sports Business Journal, 1.

6. Bernstein, A. (2000a, May 29). And the winner is… Sports Business Journal, 1.

7. Bernstein, A. (2000b, May 29). Commissions are not enough; agencies want to own events. Sports Business Journal, 1.

8. Brand, M. (2005, April 6). Show colleges the money: university sports in need of some commercialization. The Chicago Tribune, 25.

9. Burden, W & Li, M. (2003). Differentiation of NCAA Division I athletic departments in outsourcing of sport marketing operations: A discriminant analysis of financial-related institutional variables. International Sports Journal, 7(2), 74-81.

10. Burden, W. & Li, M. (2005). Circumstantial factors and institutions’ outsourcing decisions on marketing operations. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 14(2), 125-131.

11. Burden, W., Li, M., Masiu, A. & Savini, C. (2006). Outsourcing intercollegiate sport marketing operation: An essay on media rights holders’ strategic partnership decisions. International Journal of Sport Management, 7, 474-490.

12. Cawley, R. (1999, March 22). Q&A: Jim Host. Sports Business Journal, 17.

13. Cohen, A. (1999a, July). Schools for sale. Athletic Business, 32-33.

14. Cohen, A. (1999b, December). Package deals. Athletic Business, 29-30.

15. Conklin, A.R. (1999, July). Dollars signs. Athletic Business, 45-51.

16. Conlon, J. K. & Giovagnoli, M. (1998). The Power of Two: How Companies of All Sizes Can Build Alliance Networks That Generate Business Opportunities. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

17. IMG to buy Host Communication. (2007, November 12). Business First of Louisville. Retrieved December 1, 2007, from http://louisville.bizjournals.com/louisville/stories/2007/11/12/daily4.html

18. Greengard, S. (2005). Bundled outsourcing: Proceed with caution Business Finance,11(7), 49-52.

19. Johnson, K. (2005, February 21-27). A marketing slam dunk? SportsBusiness Journal, 17-21.

20. Jordan, J. (2004, October 13). UK accepts $80 million sports marketing deal. The Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved November 16, 2004, from http://www.kentucky.com/mld/kentucky/business/9904600.htm

21. Krisel, S. (2005, April 27). Corporate sponsorship helps fund athletics. The Exponent. Retrieved April 27, 2005, from http://www.purdueexponent.org/interface/bebop/showstory.php?date=200

5/04/27§ion=sports&storyid=corporatesponsorship

22. Lachowetz. T, Sutton, W.A., & McDonald, M.A. (2000, October/November). Selling the big pictures. Athletic Management, 12(6). Retrieved February 12, 2005, from

http://www.momentummedia.com/articles/am/am1206/ovoselling.htm

23. Lee, J. (2004, June 7). Schools leaving money on table. SportsBusiness Journal, 1.

24. Li, M. & Burden, W. (2002). Outsourcing sport marketing operations by NCAA Division I athletic programs: an exploratory study. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 11(4), 226-232.

25. Li, M. & Burden, W. (2004). Institutional control, availability of internal resources and other related variables in affecting athletic administrators’ outsourcing decisions. International Journal of Sport Management, 5(4), 1-11.

26. Parise, S. & Casher, A. (2003). Alliance portfolios: Designing and managing your network of business-partner relationship. Academy of Management Executive, 17(4), 25-39.

27. Schifrin, M. 2001. Partner or perish. Forbes, 167(12), 26-28.

28. Smith, M. (2004, October 13). UK lands $80 million marketing package. The Courier-Journal. Retrieved October 13, 2004, from http://www.courier-journal.com/cjsports/news2004/10/13/C1-cats1013-7973.html

29. Smith, M. (2009, March 30). Ohio State lands $110M deal. SportsBusiness Journal, 1.

30. Spekman, R. E. & Isabella, L. A. (2000). Alliance Competence: Maximizing the Value of Your Partnerships. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

31. Steinbach, P. (2002, October). The financial score. Athletic Business, 87-94.

32. Suggs, W. (2001a, May 25). Pac-10 faculties seek to halt ‘arms race’ in athletics. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 43.

33. Suggs, W. (2001b, November 23). Big Ten faculty group calls for reform in college sports. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 33.

34. The Interview – Jim Host. (2005, March). Sports Travel, 9(3), 38-39.

35. Tomasini, N. (2004). National Collegiate Athletic Association corporate sponsor objectives: are there differences between Divisions I-A, I-AA, and I-AAA? Sports Marketing Quarterly, 13(4), 216-226.

36. Walker, M., Sartore, M., & Taylor, R. (2009). Outsourced marketing: it’s the communication that matters. Management Decisions, 47(6), 895-918.

37. Wills, E. (2005, May 24). Knight Commission criticizes spending on college sports in wide-ranging meeting. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved May 25, 2005, from

http://chronicle.com/temp/email.php?id=u77dvawp4ioaywops16s23vqylmzebep

38. Zullo, R.H. (2000). A study of the level of satisfaction with outsourcing marketing groups at major division I-A national collegiate athletic association schools. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Ranking College Football Programs Based Upon Athletic Performance and Academic Success

Submitted by Frederick Wiseman & John Friar

ABSTRACT

The NCAA has become increasingly concerned about the academic well-being of its student-athletes and has adopted a new measure to monitor the academic progress of each collegiate team that grants athletic scholarships. It is called the Academic Progress Rate (APR) and measures the extent to which a team’s student-athletes retain their eligibility and stay in school on a semester by semester basis. Lucas and Lovaglia (2005) believed that the ranking of collegiate teams based upon both academic success and athletic performance would be of value to numerous constituencies and developed such a ranking system for collegiate football teams. In this paper, we build upon their work by constructing a statistically based ranking system that utilizes a team’s multi-year APR and their Average Saragin Rating. During the 2007-2010 academic years that were investigated, the three top ranked teams were Ohio State, Boise State and the University of Florida. The results also revealed a moderate and positive correlation between a team’s multi-year APR and its Average Saragin Rating.

INTRODUCTION

The NCAA recently implemented a number of changes that were designed to improve the academic well-being of student-athletes. These changes fell into four categories: (i) new initial eligibility standards, (ii) new requirements for two-year college transfers, (iii) new requirements for post-season eligibility, and (iv) new penalty structures and thresholds. Refer to Harrison (2012) for an excellent review of these changes and for a history of the NCAA’s commitment to the academic success of student-athletes. A key component of this academic reform movement has been the development and adoption of the APR for each collegiate sports team that grants athletic scholarships (8). The APR measures the extent to which student-athletes are maintaining their eligibility and staying in school. It represents a significant improvement over previous measures of academic success because it provides specific information on the extent to which current student-athletes are satisfactorily completing the academic requirements that are necessary to obtain a degree.

The APR is a number between 0 and 1000. On a term by term basis, each student-athlete receiving athletic aid earns one retention point for staying in school and one eligibility point for remaining academically eligible. Excluded from this calculation are those team members who decide either to leave school to sign a professional contract or to transfer to another school, provided in each instance they were still eligible to compete when they left school. The total points earned by team members are divided by the possible number of total points that could be earned, and then this proportion is multiplied by one thousand. The resulting figure is the APR score for the team. Defined in this manner, the APR provides an up-to-date measure that can be used to evaluate the academic success and the academic culture of collegiate sports teams at a given point in time. It also allows comparisons to be made between teams playing the same sport throughout the country. Each year, the NCAA reports for each team both a single-year APR and a multi-year APR, based upon the last four seasons.

For the 2012-2013 academic year, teams in all sports must have obtained a multi-year APR of at least 900 or have an average single-year APR of at least 930 in the last two academic years in order to be eligible to compete in post-season play. This requirement disqualified the University of Connecticut’s Men’s Basketball team, the 2010-2011 national champions, from participating in the 2012-2013 tournament. The APR requirement becomes more stringent each year until it reaches its desired multi-year standard of 930 in 2015-2016.

The use and wide-spread acceptance of the multi-year APR as an appropriate measure of academic success has had a dramatic effect on college sports teams and athletic departments. It is the single most important measure of academic success for the NCAA and is closely monitored by athletic directors, coaches, and academic advisors. This is especially true at the elite revenue producing schools competing in football and basketball where the imposition of penalties can result in a substantial loss of revenue and prestige.

Lucas and Lovaglia (2005) and, more recently, Crotty (2012), indicated that it would be of value to rank college athletic teams using a combined measure of academic success and athletic performance. They argued that such a measure would be of benefit not only to university administrators when evaluating their athletic programs, but also to potential student-athletes when choosing a college to attend. Lucas and Lovaglia proposed such a measure for Division 1 football programs and called it the Student-Athlete Performance Rate (SAPR). To arrive at a team’s SAPR score, they added a team’s single year APR to a team’s Athletic Success Rate (ASR). Unfortunately, the ASR that was developed was seriously flawed because it did not provide a valid measure of a team’s athletic performance for a particular period in time, but rather it was designed to measure the “well-being” of a team over some undefined period of time. For example, included in the construction of the ASR were such factors as a team’s all-time winning percentage, its average attendance in a particular year, the number of conference championships won in the last five years, and the number of student-athletes that went on to play in the National Football League.

In this paper, we build upon this previous work by describing a statistical ranking system which is based upon valid measures of both athletic success and athletic performance. This ranking system is then applied to the 120 members of the NCAA’s Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS). The methods used to create such a ranking system are described in the next section.

METHODS

A valid measure of academic success and a valid measure of athletic performance are required to construct an overall ranking of schools. For the academic success measure, we use a school’s multi-year APR score (http://www.ncaa.org). At present, the latest available multi-year APRs are based upon the 2007-2010 seasons. Since the multi-year APR is based upon a four year period of time, the athletic performance measure used should also cover this same time period. Various performance measures were considered before it was decided to use the average of the Saragin ratings at the end of each season for each team. A team’s Saragin rating is based on three factors (i) won/loss record, (ii) strength of schedule, and (iii) margin of victory. The Saragin ratings for college football teams have been published on a weekly basis by USA TODAY since 1998 and have been used to help determine which teams will play in the national championship game. The ratings can be found at: http://www.usatoday.com/sports/sagarin-archive.htm.

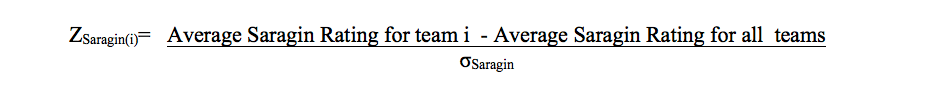

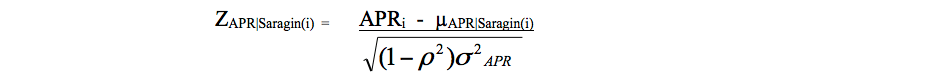

To obtain an overall ranking of schools, we employ a methodology using two independent standardized z-scores as previously described by Wiseman et al. (2007). With this methodology, we first have to determine whether a correlation exists between a team’s multi-year APR and its Average Saragin Rating. If a correlation does exist, we cannot simply compute standardized z-scores for each individual rating and add them together to obtain an overall measure. Instead, we need to construct two standardized z-scores which are independent and which take into account the correlation that exists. For each school, these z-scores would be: (i) the standardized z-score for the Average Saragin Rating and (ii) the standardized z-score for the multi-year APR given the Average Saragin Rating. The first standardized z-score would be computed as follows:

For the second z-score, we would need to calculate the expected multi-year APR given the Average Saragin Rating and the standard deviation of the multi-year APR given the Average Saragin Rating. To obtain these values, we compute:

where µAPR is the average multi-year APR, p is the correlation coefficient between the Average Saragin Rating and the multi-year APR, and σAPR is the standard deviation of the multi-year APRs. Given the above, the second z-score would be:

Statistical theory concerning bivariate normal distributions tells us that the standardized z-scores for the Average Saragin Rating and for the multi-year APR given the Average Saragin Rating will each have a mean of 0.0 and a standard deviation of 1.0. Further, since the two z-scores are statistically independent, they can be added together to obtain an overall summated z-score for combined athletic performance and academic success. The higher the overall value of Zsum = ZSaragin(i)+ ZAPR|Saragin, the higher the overall ranking.

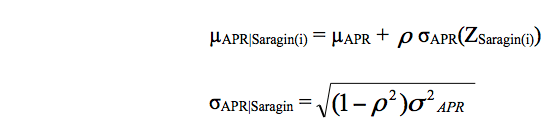

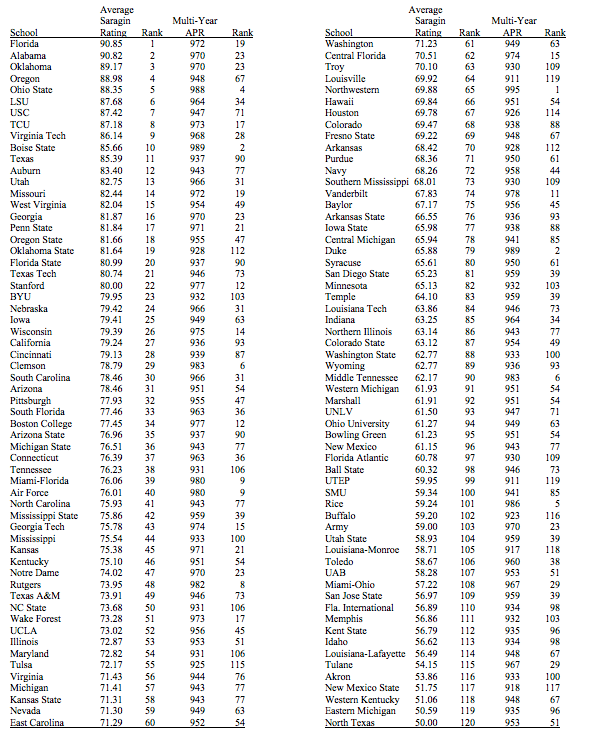

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the Average Saragin Ratings for the four seasons as well as the multi-year APR score for all 120 schools. The average Saragin rating (µSaragin) was 70.62 with a standard deviation (σSaragin) of 10.03. The highest average ratings were obtained by the following five universities: Florida (90.85), Alabama (90.82), Oklahoma (89.17), Oregon (88.98), and Ohio State (88.35). The average multi-year APR (µAPR) was 951.97 with a standard deviation (σAPR) of 18.27. The five highest ranked universities according to their multi-year APR were Northwestern (995), Boise State (989), Duke (989), Ohio State (988), and Rice (986).

Table 1. Average Saragin Rating and Multi-Year APR for Schools in the Football Bowl Subdivision: 2007-2010

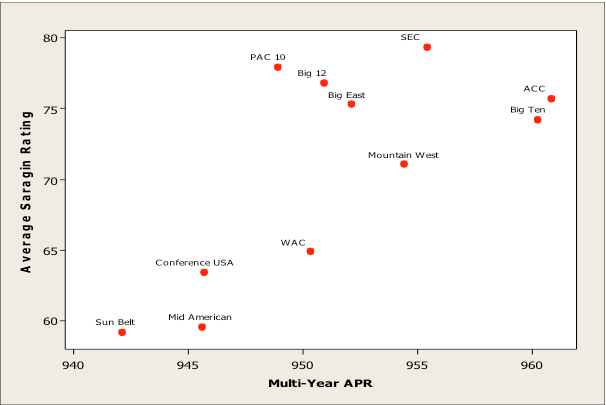

When the individual schools were grouped by conference, the Average Saragin Ratings of the six major conferences (SEC, Big East, Pac 10, Big 10, Big 12 and ACC) were all greater than the five smaller conferences (Mid-American, Sun Belt, Mountain West, Conference USA and Western Athletic). In terms of the academic success measure, similar results were obtained except for the Mountain West conference which had a higher multi-year APR than three of the major conferences — the Pac 10, the Big East and the Big 12. These results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Scatterplot of Average Saragin Rating and Average Multi-Year APR by Conference: 2007-2010

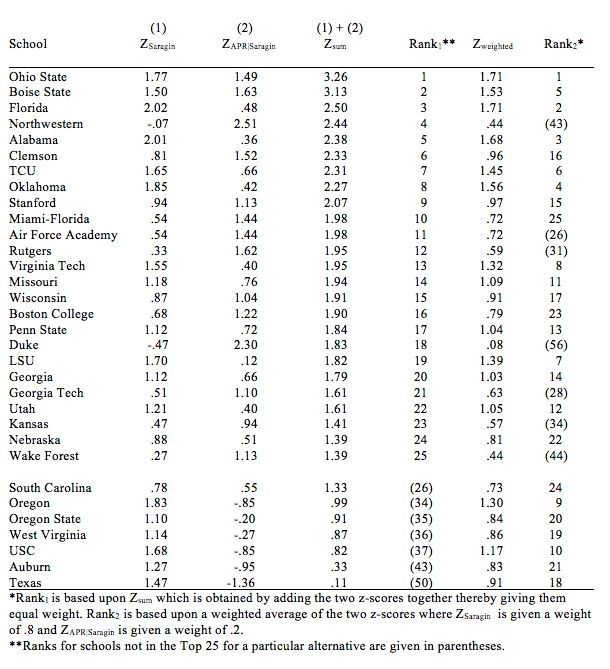

A correlation of r =.32 (p<.01) was found between the Average Saragin Rating and the multi-year APR. This finding is similar to results obtained in earlier studies that used graduation rates as the measure of academic success (1,3,6,7,9,10). Universities that ranked highly on both measures were Florida (1st and 19th), Alabama (2nd and 23rd), Oklahoma (3rd and 23rd), Ohio State (5th and 4th), Boise State (10th and 2nd), and TCU (8th and 17th). Given the correlation that existed between multi-year APR and the Average Saragin Rating, the two independent z-scores (ZSaragin(i) and ZAPR|Saragin(i)) were obtained and then added together for each of the 120 schools. These scores are presented in Table 2 and the top ranked school for the four year period was Ohio State which had the fifth highest Average Saragin Rating of 88.35 and the fourth highest multi-year APR of 988. Boise State, Florida, Alabama, and Northwestern had the next highest rankings. The Anderson-Darling test was used to test for normality of the two z-scores and the test results revealed that the normality assumption could not be rejected at the 5% level of significance.

Table 2. Comparison of the Top 25 Ranked Schools using Alternative Ranking Methods: 2007-2010*

The previous ranking of schools gave equal weight to athletic performance and to academic success. Giving such equal weight to each of the components was originally suggested by Lucas and Lovaglia (2005). However, one could also argue that more weight should be given to the athletic performance measure since this would be a national ranking of football teams. Our methodology allows for that possibility. For example, if we decided to give the first z-score (ZSaragin) a weight of .8 and the second z-score (ZAPR|Saragin) a weight of .2, we could obtain a weighted average of the two z-scores and re-rank the schools based upon this weighted average. The results of such a weighting are shown in Table 3 and, once again, the top ranked school was Ohio State. It was followed by Florida, Alabama, Oklahoma, and Boise State. Now, however, seven new schools entered into the Top 25. These were schools that had relatively strong Average Saragin Ratings but relatively poorer multi-year APRs. They were South Carolina, Oregon, Oregon State, West Virginia, USC, Auburn, and Texas. The schools that they replaced were Northwestern, Air Force Academy, Rutgers, Duke, Georgia Tech, Kansas, and Wake Forest. These latter schools are generally better known for their academics than for their football success.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted in order to determine how the rankings would have changed if different weights were used. These analyses were conducted for the following three sets of weights –(.9, .1), (.75, .25) and (.7, .3), where the first number is the weight given to the Average Saragin Rating and the second number is the weight given to the multi-year APR given the Average Saragin Rating. The rank correlations between each of these three weighting schemes and the (.8, .2) weighting scheme that was originally used were .97, .98 and .91, respectively. This indicates that the actual rankings were relatively insensitive to the actual weights used when the weight given to the Average Saragin Rating was .7 or higher.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that it is possible to have a combined ranking of athletic teams based upon athletic and academic success. The results of this ranking for the 2007-2010 period indicated a positive correlation between athletic success and academic success. The analysis also revealed that the top performing football schools are more likely to ensure that their student-athletes stay in school and maintain their eligibility. This makes sense because such schools have the most to lose financially if their teams are not eligible for post-season play. These teams also spend a considerable amount of time, effort, and money recruiting promising student-athletes. They also generate a substantial amount of money and provide a high level of academic support and facilities for its student-athletes in order to help them maintain their eligibility. Such a high level of support may not be available for student-athletes at poorer performing schools with fewer resources devoted to their academic well-being.

Additionally, many of these large and successful schools offer specific programs geared to the student-athlete population, thus increasing the likelihood of their academic success. Similarly, these schools may also be less likely to take a chance on a potential student-athlete with significant athletic potential, but with very little chance of academic success at their school.

CONCLUSION

The ranking of FBS teams was based upon their success in the classroom and their performance on the football field. Rankings for other collegiate sports, both male and female, including the non-revenue sports could easily be obtained using the methodology described. In addition, it would be of interest to identify the key factors that lead certain teams to have high APRs, while other teams have low APRs. Such an investigation is the subject of future research, and should be of value to numerous groups including the NCAA as it continues with its academic reform movement.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

Critics and some members of the NCAA have argued that the organization should increase its emphasis on the academic well-being of its student-athletes. This has led to the academic reform movement that has taken place in recent years. With the methods presented here, the NCAA could recognize schools that excel both on the field and in the classroom. It also gives member schools a scorecard as to how well its team is doing on and off the field. The results also indicate that the schools with the weakest football teams in the non-BCS conferences, often times, are also the ones whose teams have the lowest multi-year APRs. Reasons for these differences should be investigated so that corrective actions can be undertaken which will enable all student-athletes to increase their likelihood of academic success.

REFERENCES

1. Comeau, E. (2005). Predictors of academic advancement among student-athletes in the revenue-producing sports of men’s basketball and football. The Sport Journal, 8. Available at: http://www.thesportjournal.org/article/predictors-academic-achievement-among-student-athletes-revenue-producing-sports-mens-basketb.

2. Crotty, J. M. (2012). When it comes to academics football crushes basketball. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesmarshallcrotty/2012/01/05/northwestern-vs-rutgers-in-bcs-championship-if-education-was-yardstick/.

3. DeBrock, L., Hendricks, W., & Koenker, R. (1996). The economics of persistence: Graduation rates of athletes as labor market choice. Journal of Human Resources, 31, 513-539.

4. Harrison, W. (2012). NCAA academic performance program (APP): Future directions. Journal of Intercollegiate Sports, 5, 65-82.

5. Lucas, J. W. & Lovaglia, M. J. (2005). Can academic progress help collegiate football teams win? The Sport Journal, 8. Available at: http://www.thesportjournal.org/article/can-academic-progress-help-collegiate-football-teams-win.

6. Mangold, W. D., Bean, L. and Adams, D. (2003). The impact of intercollegiate athletics on graduation rates among major NCAA Division I universities: Implications for college persistence theory and practice. The Journal of Higher Education, 74, 540-562.

7. Mixon, F. G. & Trevino, L. J. (2005). From kickoff to commencement: the positive role of intercollegiate athletics in higher education. Economics of Education Review, 24, 97-102.

8. NCAA. (2012). Academic Progress Rate. Available at: http://www.ncaa.org/wps/wcm/connect/public/NCAA/Academics/Division+I/Academic+Progress+Rate.

9. Rishe, P. J. (1993). A reexamination of how athletic success impacts graduation rates: Comparing student-athletes to all other undergraduates – the university. American Journal of Economics and Sociology (April). Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1536-7150.00219/pdf.

10. Tucker, I. B. (2004). A reexamination of the effects of big-time football and basketball success on graduation rates and alumni giving rates. Economics of Education Review, 23, 655-661.

11. Wiseman, F., Habibullah, M. & Yilmaz, M. (2007). A new method for ranking total driving performance on the PGA Tour. The Sport Journal, 1. Available at: http://www.thesportjournal.org/article/new-method-ranking-total-driving-performance-pga-tour.

An Empirical Analysis of the Effectiveness of World Wrestling Entertainment Marketing Strategies

Submitted by Sungick Min, WonYul Bae, David Pifer and Colin Pillay

Abstract

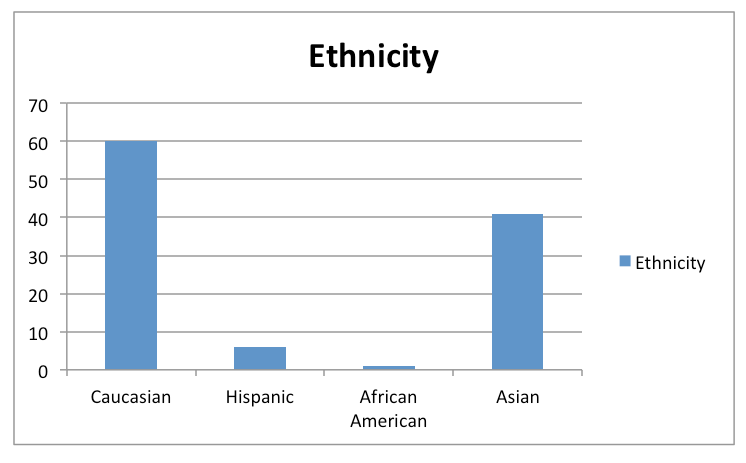

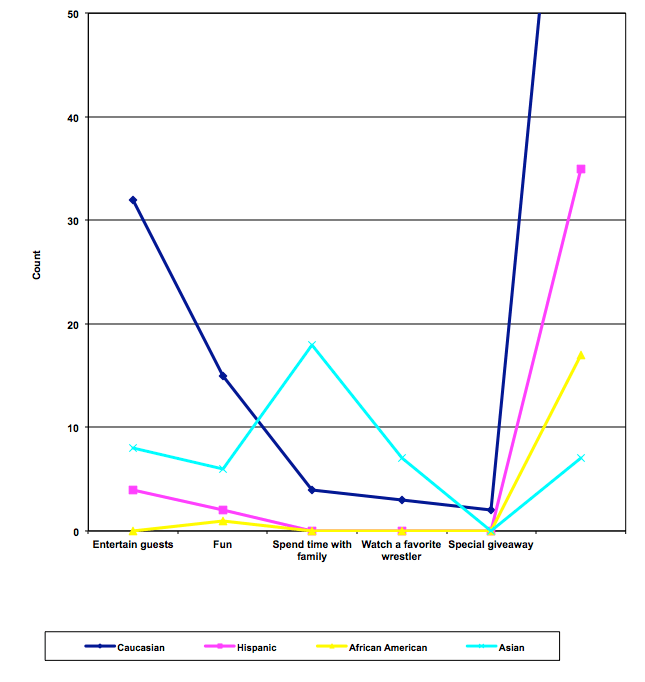

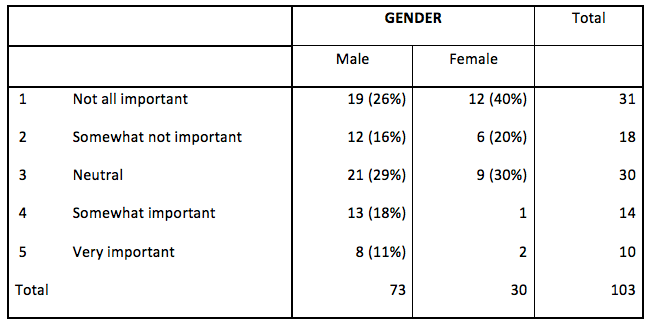

World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. (WWE), which is headquartered in Stamford, Connecticut, produces one of the most popular sporting events in the world, spans a diverse audience, and has a fanatical base and following for its entertainment value. This study was designed to investigate the numerous ways in which the company promotes and markets its brand, its programming, its events, and its products. Drawing from 107 randomly collected survey questionnaires, the results of this research indicated a variety of significant differences in the effects of WWE marketing promotions on the age, income, marital status, and ethnicity demographics. These findings can in turn be used to help the WWE target designated consumer segments with the appropriate resources and marketing strategies as the company strives to increase future opportunities for success. Further samples from other areas in the country are needed, though, to verify if the regionally recognized inclination is consistent across the country. In addition, research should be performed at different times of the year to clarify seasonal sport preferences.

INTRODUCTION

Professional wrestling fans receive different reactions from people. Some people think it is “cool” to be a fan; others are disappointed because they consider it to be faked. Fans respond that they enjoy the entertainment value of professional wrestling. According to Ball (1990), wrestling fans tend to be stereotyped as the “dregs of society,” a group composed mainly of lower-class people.

Nevertheless, professional wrestling is also a tremendous entertainment business and has become an addiction for a large portion of young Americans. Ball (1990) stated, “Professional wrestling in the United States provides an ideal platform for the study of entertainment-culture and portrays some of the richest symbolism in society today” (p. 4).

It incorporates action in the arena, and sometimes outside the arena. It is an action adventure show, a cartoon, drama, and a sitcom. It is like a big soap opera for men, a hybrid of everything ever seen on television. World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. (WWE), which produces some of the most popular shows in the world and reaches a diverse audience, has an enormous fan base and following for its entertainment value. As one of television’s most unique shows, it draws upon many other successful forms of entertainment. The continuing story lines are familiar to viewers of soap operas. The action, adventure, and racier elements draw their motivation from the best that sports and Hollywood have to offer. According to Gresseon (1998), professional wrestling has gone from a dull participant ritual to an exciting, action-filled form of entertainment.

The action in WWE events may be “fake,” but the entertainment value of World Wrestling created by Vincent and Linda McMahon is very real. Gresson (1998) asserted that wrestling has taken into consideration the audience’s needs and successfully translated them into spectacular shows that draw spectacular profits. The WWE has dominated its market and has established its brand in the minds of the American public. As an integrated media and entertainment company, the WWE is principally engaged in the development, production, and marketing of television programming, pay-per-view programming, live events, and the licensing and sale of branded consumer products featuring its successful World Wrestling Entertainment brand.

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

In WWE’s 2006 annual report, net revenues of $400.1 million were generated, while an income from continuing operations of $55.2 million, before interest, taxes, depreciation, amortizations, stock options, and other non-cash charges, was reported.

WWE is incredibly prevalent in the male demographic, especially those aged 14 to 34. The company has been involved in the entertainment business for over 20 years and has established the brand as one of the most popular forms of entertainment today. According to Stotlar (2005), demographic changes in the United States population have directly influenced sport marketing. Brenner (2004) indicated that population trends have caused organizations to take a long, hard look at marketing efforts as teams and leagues find that there is no single, correct approach. To increase market penetration, marketers often discuss how to reach Hispanic, Asian, or other ethnic consumer groups, but oversimplify the challenge by applying such labels. According to WWE, its operations are organized around two principal activities:

1. Creation, marketing and distribution of live and televised entertainment, including the

sale of advertising time on its television programs; and

2. Marketing and promotion of its branded merchandise.

In an effort to further exploit and bolster its business, WWE launched a brand extension that created two separate and distinct brands, “Raw” and “SmackDown!” Each extension has its own distinct story lines, thus enabling the company to have two separate live event tours. The two tours permit the company to visit new domestic markets while touring internationally on a more frequent basis. In addition, WWE currently maintains licensing agreements with approximately 70 licensees worldwide. The company logo and images of WWE characters appear on thousands of retail products, including various types of apparel, toys, video games, and a wide assortment of other items.

According to WWE’s 2006 annual report, the company produces and promotes wrestling matches for TV and live audiences. Its nine hours of TV programming each week include “Raw”, a top US cable program, and “Smackdown!”, the highest-rated UPN show. Most of its programming airs on Viacom outlets, including MTV, TNN, and UPN. WWE also produces 14 pay-per-view programs and about 240 live events each year, licenses characters for merchandising, and sells videos and DVDs that showcase such wrestling stars as “The Rock”, “Hollywood Hulk Hogan”, and “The Undertaker.”

WWE’s success prompted this study, which set out to investigate the numerous ways in which the company promotes and markets its brand, its programming, its events, and its products. Kwon and Armstrong (2004) asserted that one of the most crucial elements of sport marketing involves segmenting the market of sport consumers into smaller, homogeneous groups for which specific marketing strategies can be cultivated. Accordingly, this study examined the different results of WWE promotions and marketing based on age, income, marital status, and ethnicity.

Pitts and Stotlar (2002) defined sport marketing as “the process of designing and implementing activities for the production, pricing, promotion, and distribution of a sport product to satisfy the needs or desires of consumers and to achieve the company’s goals” (p. 80).

Understanding the “4 Ps of Marketing” is crucial to any successful marketing channels in an organization. In traditional marketing, the “4 Ps of Marketing”, a concept coined by E. Jerome McCarthy (McCarthy & Perreault, 1990), specifically refers to the following:

Product: the essence of the product or service that includes product lines, product extensions, and the meeting of new consumer needs within the targeted group of customers.

Price: shows the desired image a company wants to portray about a product or service while taking into consideration competitors’ prices, available discounts, and market share.

Place: the actual, physical distribution of a product or service. This can include the transporting of goods to wholesale and retail outlets or the geographic location of a business or organization.

Promotions: carrying messages about products and services to potential consumers. This can be performed through publicity, advertising, or other means of communication.

A brief overview of the 4 Ps as they relate to the WWE will serve as a base from which to understand WWE’s success. To begin, the WWE “products” are its superstars – “The Rock”, “Trish Stratus”, “Stone Cold Steve Austin”, and “The Undertaker”. These superstars are professional and skilled in the portrayal of popular characters. One of WWE’s top superstars, “The Rock”, the son of a Samoan homemaker and an African-American pro wrestler, became a feature film action hero in Universal’s blockbuster, “The Scorpion King”. WWE has a vastly increased talent pool that translates directly to brand extension and additional revenue streams producing more pay-per-view events, more live events, more international tours, more branded merchandise, and more new television programming with new stars and new brands outside the genre.

Compared to other sports leagues, the WWE ticket “price” is one of the most expensive. According to the WWE website (2007), the average ticket price for three live events in Asia in March 2002 was $63.00 and the average ticket price for live events in the United States was $36.00. Each of WWE’s other 11 domestic pay-per-view events have a suggested retail price of $34.95, up from $29.95. Compared to the baseball ticket, ESPN (2007) indicates that the lowest average price is $13.79.

According to the WWE annual report (2006), it has major arenas, such as Madison Square Garden in New York City, Arrowhead Pond of Anaheim, California; Allstate Arena in Chicago, First Union Center in Philadelphia, Fleet Center in Boston, and Earls Court in London, England. These major arenas represent the “place” in the marketing mix. WWE has a 46,500-square-foot entertainment complex located in Times Square. The complex boasts a 600-seat restaurant and 2,200 square feet of retail space. The complex provides for a variety of entertainment uses, including:

1. Airing WWE’s regularly scheduled TV shows and pay-per-views;

2. Hosting concerts and other live events, including press conferences,

stockholder meetings and product launches;

3. A night club;

4. Appearances and autograph sessions featuring performers; and,

5. Banquets, birthday parties and other social and corporate functions.

“Promotion” is the final P in the marketing mix to be discussed. According to WWE, the company promotes and markets its brand, its programming, its events, and its products in numerous ways, including: