Authors: Brenda L. Vogel, Jeff Kress, and Daniel R. Jeske

Corresponding Author:

Jeff Kress, Ph.D.

Department of Kinesiology

1250 Bellflower Blvd. – MS 4901, HHS2-103

Long Beach, CA 90840

jeff.kress@csulb.edu

949-375-3958

Brenda L.Vogel is a Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice and the Director of the School of Criminology, Criminal Justice, and Emergency Management at California State University, Long Beach. She served as the CSULB NCAA Faculty Athletics Representative from 2007-2015.

Jeff Kress is an Associate Professor in the Department of Kinesiology at California State University, Long Beach and teaches in the area of Physical Education Teacher. His research interests have been in the area of sport performance enhancement through psychological methods.

Daniel Jeske is a Professor, in the Department of Statistics at the University of California, Riverside. He has served as the UCR NCAA Faculty Athletics Representative. He is an elected Fellow of the American Statistical Associationand an Elected Member of the International Statistical Institute. He has published over 100 peer-reviewed journal articles and is a co-inventor on 10 U.S. Patents and is currently the Editor-in-Chief of The American Statistician.

Student-Athletes vs. Athlete-Students: The academic success, campus involvement, and future goals of Division I student athletes who were university bound compared to those who would not have attended a university had they not been an athlete.

ABSTRACT

This study examined the differences between two groups of Division I student athletes: those who would have attended a 4-year university regardless of their participation in athletics and those who would not have attended a 4-year university had it not been for the opportunity afforded them through their athletic ability. The researchers examined a number of academic factors including GPA, participation in intensive academic experiences, class participation and preparation, perception of academic experience, importance of graduation, major selection, and participation in extracurricular activities, future goals, and identification as an athlete or student. The data from the NCAA’s Growth, Opportunities, Aspirations and Learning of Students in College (GOALS) survey that was administered to a nationwide, random sample of NCAA student athletes in 2006 are discussed. Our results suggest that there were significant differences between the two groups in several of the domains measured. For example, our findings suggest that student athletes who identify as athletes first and students second think less about academics when choosing a college, are less likely to major in mathematics and science, are less likely to select a major to prepare for graduate school or a specific career, have lower GPAs, are less likely to participate in classes, are less likely to be involved in extracurricular activities, are less willing to sacrifice on athletics participation for academics, feel graduation is less important to them and to their families, and believe becoming a professional athlete is more likely. Implications for the NCAA and college athletics programs are discussed.

Keywords: Student-Athletes, Athlete Students, G.O.A.L.s survey

INTRODUCTION

“’Running opened up a lot of opportunities for me, coming from a family that didn’t know about college,’ he says. ‘If it wasn’t for running, I probably wouldn’t have gone to college and I wouldn’t be where I am today’” (15).

This quote, from a cross-country student athlete from Willamette University, illustrates one of the more compelling arguments in support of intercollegiate athletics: athletic competition can provide educational opportunities to young people who would not have otherwise attended college. It is common for coaches to recruit a prospective student athlete because of her/his exceptional athletic ability even if s/he has marginal academic qualifications. Indeed, most universities have provisions for “specially” admitting students who do not qualify for regular admission. Those students include not only athletes, but also artists, the children of donors or political figures, celebrities, or friends of campus administrators and legacies. Nonetheless, some of those prospective student athletes may have never even considered attending a college or university, let alone be prepared for attendance.

The reasons some high-school athletes do not intend to attend a university are many. Some come from disadvantaged backgrounds where attending a university is not a consideration (6). Some may have intended to enroll in a junior college. Some of them may have lacked appropriate academic counseling while in high school or concentrated their energies on competing with their high school team or an elite club team rather than on their studies. Still others are international students who spent their high school years competing on junior national teams and neglected their studies.

Regardless of the reasons why they were not university-bound in the first place, many of these students end up on university campuses competing and attending class alongside other student athletes and non-athletes who were university-bound all along. While several studies have examined student athletes’ academic performance and the predictors of their academic success (13,24,25,27), there is no research that compares the academic success of student-athletes who were university-bound regardless of their involvement in sports, to those who would not have attended university were it not for their athletic talent. This study aims to address this gap in the literature.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The challenge of balancing academic standards with athletic competitiveness is not new. Since its inception in 1906, National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) member intuitions have wrestled with the same issues that we face today: the extreme pressure to win, which is compounded by the commercialization of sport, and the need for regulations and a regulatory body to ensure fairness and safety (26). Today, the NCAA’s primary responsibility is to protect student athletes’ wellbeing and to provide them with the skills to succeed on the playing field, in the classroom, and throughout life. According to the most current NCAA Division I Manual (20) under the heading “Purposes,” section 1.2 reads: “To initiate, stimulate and improve intercollegiate athletics programs for student-athletes and to promote and develop educational leadership, physical fitness, athletics excellence and athletics participation as a recreational pursuit. (p. 1)” And in the Principle of Student Athlete Well Being section 2.2 reads, “Intercollegiate athletics programs shall be conducted in a manner designed to protect and enhance the physical and educational well-being of student-athletes. (p. 3)”

Despite the stated purpose, with billions of dollars on the line (through TV contracts, salaries, incentives, etc.) athletic programs, athletic directors, and coaches face tremendous pressure to build and maintain winning programs. A series of scandals rocked college sports in the 1980’s in which 109 colleges and universities were censured, sanctioned, or put on probation by the NCAA. That number included more than half the universities playing at the NCAA’s top competitive level (57 institutions out of 106). At that time, nearly a third of present and former professional football players responding to a survey near the end of the decade said they accepted illicit payments while in college and more than half said they saw nothing wrong with the practice (17). Add to that another survey showing that among 100 big-time schools, 35 had graduation rates under 20 percent for their basketball players and 14 had the same low rate for their football players (17).

As a result, the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics (known simply as the Knight Commission) was formed in 1989. Its founding co-chairmen were Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, president of the University of Notre Dame, and William C. Friday, former president of the University of North Carolina. Shortly before the establishment of the Commission, Time Magazine (10) ran an article questioning whether student athletes were really getting an education at all. “There is an obsession with winning and moneymaking that is pervading the noblest ideals of both sports and education in America.” Its victims, Time went on to say, were not just athletes who found the promise of an education a sham but “the colleges and universities that participate in an educational travesty — a farce that devalues every degree and denigrates the mission of higher education.” (p. 54)

Among its initial recommendations, the 1991 Knight Commission report advocated the “one-plus-three” model, a new structure of reform in which the “one” — presidential control — is directed toward the “three” — academic integrity, financial integrity and independent certification. With respect to academic integrity, the commission wrote that athletes “should not be considered for enrollment at a college or university unless they give reasonable promise of being successful at that institution in a course of study leading to an academic degree Despite the fact that the Commission held no formal authority, nearly two-thirds of its specific recommendations were endorsed by the NCAA by 1993. Moving forward, “likelihood of graduation,” became the standard against which universities would measure the admission of student athletes (17).

In 2001, The Knight Commission reconvened to assess what had transpired during the decade following their initial report and to assess the state of college athletics at the beginning of the new century. While they found some progress had been made, their findings were equally if not more disturbing than those found in the first report. They found that the graduation rates of athletes in Division 1A basketball and football at top institutions to be “dismally low-and in some cases failing.” In basketball, the five-year graduation rate was 34 percent. The graduation rate for white football players was 55 percent and for black football players 42 percent. Part of the problem according to the report was: “Athletes are often admitted to institutions where they do not have a reasonable chance to graduate. They are athlete-students, brought into the collegiate mix more as performers than aspiring undergraduates. Their ambiguous academic credentials lead to chronic classroom failures or chronic cover-ups of their academic deficiencies. As soon as they arrive on campus, they are immersed in the demands of their sports. In light of these circumstances, academic failure, far from being a surprise, is almost inevitable” (16).

Academic Progress Rate

In 2003, the NCAA instituted the Academic Progress Rate (APR). The APR was designed to improve the academic performance of student athletes (24) and to increase graduation rates (21). It “holds institutions accountable for the academic progress of their student-athletes through a team-based metric that accounts for the eligibility and retention of each student-athlete for each academic term” (20). Teams must maintain a minimum APR or face an array of penalties including reduced practice time, competition reductions, scholarship reductions, and post-season bans (20). In practice, the APR has changed the way coaches recruit, making them less likely to “take a chance” on a recruit who may be less academically prepared and who has the potential to cost them an APR point. It has also changed the way athletic administrators make decisions. “How will this affect our APR?” is a question administrators ask when considering resource allocation, travel schedules, recruiting budgets, etc. (C. Masner, personal communication, March 21, 2017).

Since its inception, research suggests that the APR has increased eligibility, retention, and graduation of student athletes (21). Other reforms, including changes to initial eligibility requirements and progress toward degree rules have certainly had a part in the academic gains as well (21). Nonetheless, overall student athlete academic success has improved since the advent of the APR system.

Special Admissions

Despite the institution of the APR and the emphasis on academic success, nearly all universities offer some form of “special admission” to select students whether they are the children of donors or influential community members, exceptional musicians, talented actors, skilled athletes, or members of another targeted group. In fact, the NCAA addresses this practice directly through its Bylaw 14.1.1.1 that states, “A student-athlete may be admitted under a special exception to the institution’s normal entrance requirements if the discretionary authority of the president or chancellor (or designated admissions officer or committee) to grant such exceptions is set forth in an official document published by the university (e.g., official catalog) that describes the institution’s admissions requirements” (20).

Nonetheless, student-athletes who are specially admitted characteristically enter with borderline or below SAT, ACT and or academic records (18, 21). While it is not known how many student athletes are admitted each year under special circumstances nationally, according to Knobler (18) “more than half of scholarship athletes at the University of Georgia, the University of Wisconsin, Clemson University, UCLA, Rutgers University, Texas A&M, University, and Louisiana State University were special admits.”

University presidents, athletic directors, and coaches struggle with the recruitment of top athletes whose academic qualifications are marginal (or worse). Many coaches make the argument that “if we don’t admit him, then our conference rival will!” A senior administrator from a prominent Division IA university explained, “…we are going to participate in athletics, and we will recruit students who have a good or reasonable chance of succeeding here in order to be competitive in the NCAA” (7).

Admitting student-athletes with a “reasonable chance” of graduation while remaining competitive in a national arena is a prevalent pattern as typified by the University of Michigan President Mark Schlissel who said, “We admit students who aren’t as qualified, and it’s probably the kids that we admit that can’t honestly, even with lots of help, do the amount of work and the quality of work it takes to make progression from year to year. An individual’s academic deficiencies are often overlooked to fill competitive rosters” (29). Tom Lifka, chairman of the committee that handles athlete admissions at the University of California, Los Angeles, a program that has won more national championships in all of sports than any other school, was quoted as saying: “If you’re going to mount a competitive program in Division I-A, and our institution is committed to do that, some flexibility in admissions of athletes is going to take place. Every institution I know in the country operates in the same way. It may or may not be a good thing, but that’s the way it is” (18).

The reality of “flexibility in admissions of athletes” is having noticeable consequences. A CNN investigation in 2014 was able to obtain the public records of several schools that revealed that most have between 7% and 18% of revenue sport athletes reading at an elementary school level (8, 23). Many student athletes in that investigation were scoring well below the SAT reading threshold for being college literate of 400, several in the 200-300’s which is an elementary reading level and too low for college classes. The national average that year was 497. The same investigation noted that on the ACT, which has 36 as its highest score and a national average of 20, most teams had an average score in the teens.

Former and current academic advisers, tutors, and professors report that it is nearly impossible to jump from an elementary to a college reading level while juggling a hectic schedule as an NCAA athlete (8). While conducting research on the academics of student athletes, Bimper (12) wrote, “Dumb jocks’ are not born; they are being systematically created and institutionally accommodated by the culture of sport that is creating this disparity we see between academic performance and graduation rates” (p. 1).

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some athletes are being recruited and admitted to universities as athletes first and as students second. These students could essentially be called “athlete-students” while the majority of college athletes are commonly referred to as “student-athletes.” Ironically, the term “student athlete” was created by former Executive Director of the NCAA Walter Byers in the 1950’s to counter attempts to require universities to pay workers’ compensation after the widow of a college football player died during a game and sued for benefits (4).

Aside from journalistic reports, there is no comprehensive, academic research comparing the academic success of “student-athletes” who were university-bound regardless of their involvement in sports, to “athlete-students” who would not have attended university were it not for their athletic talent. This study aims to address this gap in the literature.

Research Questions

With this research, the researchers sought to address ten specific research questions. The researchers used several items from the GOALS survey to represent each research question. The ten questions listed with the specific GOALS items used for each, and listed in Appendix 1.

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to whether or not athletics participation influenced university/college choice, major choice, and class selection?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to how athletic participation has affected their GPA?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their class participation and preparation?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their involvement in intensive academic experiences?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their level of participation in extracurricular activities and campus events?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to the degree to which college contributed to their personal growth and development?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to whether they consider themselves more of an athlete than a student?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their perception of their academic experience?

- Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to how important graduation is to them?

- Do Student-athletes differ from Athlete-students with respect to their future goals?

METHODOLOGY

Data and Sample

The data for this study comes from the 2006 NCAA Growth, Opportunities, Aspirations and Learning of Students in College (GOALS) survey. The survey yielded responses from over 21,000 student athletes at 627 Division I, II, and III member institutions. The current study, however, is based only on data from Division I institutions. Respondents provided information about their lives as student athletes across a spectrum of domains, including academic engagement and success, athletics experiences, social experiences, career aspirations, health and well-being, campus and team climate, and time commitments. The NCAA Research Division selected one to three teams per institution to be surveyed in order to provide representative samples within each division. The Faculty Athletics Representative (FAR) on each campus was asked to administer the surveys to the selected teams. The response rate for Division I institutions was 66%.

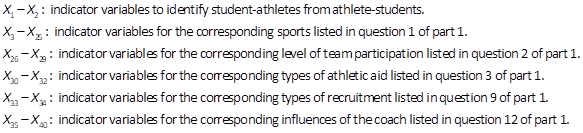

Variables

Our research focused on the views and behaviors of two groups: student-athletes and athlete-students. The GOALS survey asked respondents to respond on a six-point Likert scale to the following statement: “I would have gone to a 4-year university somewhere even if I hadn’t been an athlete.” We defined student-athletes as those who indicate (responded either strongly agree, agree, or somewhat agree) that they would have attended a 4-year university regardless of their status as an athlete. Athlete-students were defined as those who indicated (responded either strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree) they would not have attended a 4-year university had they not been an athlete. Based on these definitions, the sample included 7110 students, 6350 (89.3%) of whom were Division I student-athletes and 760 (10.7%) of whom were Division I athlete-students.[i]

The 10 control and 65 dependent variables and their frequencies and percentages for each group (athlete-students and student-athletes) are provided in Appendix One. The 65 dependent variables were grouped by research question; we used several individual GOALS survey items to measure each of our ten research questions. A review of Appendix One reveals that the distribution of student-athletes (89.3% of the overall sample) and athlete-students (10.7% of the overall sample) varies significantly across several of the dependent variables. This suggests that student-athletes and athlete students differ on a number of important measures. Many of these apparent differences are confirmed through the analysis discussed below.

Analysis

The analysis proceeded in two steps. First, we examined the differences between student-athletes and athlete-students in the 10 control variables. Second, controlling for those 10 variables, we examined the differences between the two groups on the 65 dependent variables.

We used a goodness of fit chi square analyses to determine if athlete-students and student-athletes differ on the ten control variables. The control variables included sport, academic class, level of participation, athletic aid, recruited athlete, would still attend this university if different coach, gender, race/ethnicity, father’s educational level, and mother’s educational level. The chi square distribution was used to test whether observed data differed significantly from theoretical expectations (9). In this study, the theoretical expectation was that each subgroup (e.g., women, students on full aid, etc.) would include 89.3% (.893) student-athletes (SA) and 10.7% (.107) athlete-students, (AS). This tested the null hypothesis that the distribution on each control variable attribute was: AS=.107 and SA=.893.

The second step analyzed each dependent variable using a multinomial logistic regression model. The coefficient on the grouping variable was of primary interest for exploring the ten research questions outlined above. The grouping variable was encoded as a binary variable, taking the value of 0 for student-athletes and 1 for athlete-students. The control variables were similarly encoded using corresponding sets of binary variables. All binary variables used to encode the grouping variable and the control variables were included in the multinomial logistic regression model as explanatory variables.

The multinomial logistic regression model framework can handle both nominal and ordinal dependent variables. In the case of nominal dependent variables, the model delivered estimated probabilities for each possible category of the variable, and showed how these probabilities vary depending on the covariate values. In the case of an ordinal dependent variable, the model delivered the cumulative probabilities of being at or below each category level of the variable.

For each dependent variable, the difference between the student-athlete and athlete-student populations were assessed by examining the sign and magnitude of the maximum likelihood estimate of the coefficient on the grouping variable. The null hypothesis of no difference between the two populations was tested using a Wald test (12) to determine if the estimated coefficient on the grouping variable was statistically different from zero. All analyses were carried out using the PROC LOGISTIC procedure in the software package SAS/STAT Version 9.2 Copyright © 2008 by SAS Institute Inc.

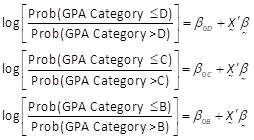

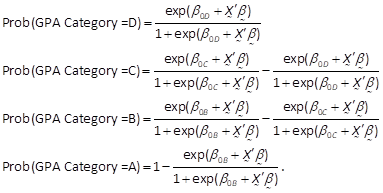

To illustrate the proposed analyses, consider the analysis of GPA. GPA is an ordinal variable with 9 categories. The researchers collapsed the 9 categories into 4 categories: the A category, with GPA between 3.5 and 4.0, the B category with GPA between 2.5 and 3.49, the C category with GPA between 1.5 and 2.49 and finally, the D category with GPA less than 1.5. After collapsing, GPA was distributed as a multinomial distribution with 4 outcome categories, which was analyzed with a multinomial logistic regression model. The independent variables in the regression were:

Multinomial logistic regression models the probability of each of the four GPA categories. This was different from typical least squares regression which models the expected value of the dependent variable. Here, GPA was a categorical variable, taking on the values A, B, C and D. So the expected value of GPA, coded this way, does not mean anything. It is more appropriate to predict the probability of each GPA category than it is to predict the mean GPA. The independent variables were used in the same way as least squares regression, except they tried to explain influences they have on the probability of each GPA category.

GPA was expressed in the model through so-called logit equations, which modeled the probability of each GPA category. Let ![]() denote the vector of all 40 indicator variables that collectively represent the grouping variable and the control variables. Let

denote the vector of all 40 indicator variables that collectively represent the grouping variable and the control variables. Let ![]() denote the vector of slopes on these variables

denote the vector of slopes on these variables ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() let, and be three intercept parameters. Since GPA is an ordinal variable, the logit equations used are so-called cumulative logit equations and are:

let, and be three intercept parameters. Since GPA is an ordinal variable, the logit equations used are so-called cumulative logit equations and are:

which can be solved for GPA category probabilities as follows:

The maximum likelihood algorithms in the SAS procedure PROC LOGSITIC produced estimates and significance tests for the ![]() parameters, and our interest was primarily in the estimate of coefficients on the indicator variables

parameters, and our interest was primarily in the estimate of coefficients on the indicator variables ![]() and

and ![]() corresponding to the grouping variable. The null hypothesis of no effect for the grouping variable was

corresponding to the grouping variable. The null hypothesis of no effect for the grouping variable was ![]() .

.

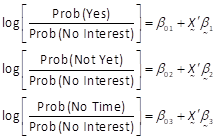

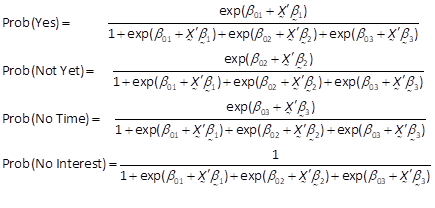

There are cases where the dependent variable was nominal, such as the items asking “which of the following experiences have you or will you be involved in during college,” where there are four outcomes (yes, not yet, no I don’t have time, and no I have no interest) that do not have a natural mathematical ordering. In cases such as this, so-called generalized logits were used when modeling the dependent variable. With generalized logits, each equation can have its own slope vector. For question 8 in part 2, there are three generalized logit equations and they are:

This can be solved for outcome probabilities as follows:

Again, maximum likelihood algorithms in the SAS procedure PROC LOGSITIC produce estimates and significance tests for the ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() parameters. The null hypothesis for no effect of the grouping variable is

parameters. The null hypothesis for no effect of the grouping variable is ![]() .

.

RESULTS

Table 1 provides the results of a series of one-way chi-squares testing if the distribution of athlete-students and student-athletes across each control variable attribute (e.g. females, seniors, etc.) differed significantly from their distribution in the overall sample. Athlete-students make up 10.7% of the overall sample and student-athletes make up 89.3% of the overall sample. A review of Table 1 suggests that the proportion of athlete-students to student-athletes varied significantly across several attributes of the ten control variables.

Table 1 Athlete-students to student-athletes across several attributes of the ten control variables |

||||

Control Variable |

Attribute |

Chi-Square1 |

p value |

Interpretation |

|

Men’s Baseball |

|

NS |

|

|

Men’s Basketball |

10.48 |

0.001 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Men’s Football |

6.30 |

0.012 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Men’s Golf |

|

NS |

|

|

Men’s Ice Hockey |

|

NS |

|

|

Men’s Lacrosse |

3.89 |

0.048 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Men’s Soccer |

|

NS |

|

|

Men’s Swimming |

|

NS |

|

|

Men’s Tennis |

|

NS |

|

|

Men’s Track (Indoor or Outdoor) |

|

NS |

|

|

Men’s Wrestling |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Basketball |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Field Hockey |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Golf |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Gymnastics |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Ice Hockey |

5.86 |

0.015 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Women’s Lacrosse |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Softball |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Soccer |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Swimming |

10.61 |

0.001 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Women’s Tennis |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Track (Indoor or Outdoor) |

|

NS |

|

|

Women’s Volleyball |

|

NS |

|

Academic Class |

||||

|

Freshman |

|

NS |

|

|

Sophomore |

|

NS |

|

|

Junior |

|

NS |

|

|

Senior |

|

NS |

|

|

Graduate Student |

|

NS |

|

Level of participation |

||||

|

First Team |

|

NS |

|

|

Second Team |

|

NS |

|

|

Third Team |

|

NS |

|

|

Practicing, not competing |

|

NS |

|

Athletic Aid |

||||

|

No |

18.06 |

0.000 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Yes, partial aid |

3.85 |

0.049 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Yes, full aid |

35.98 |

0.000 |

AS overrepresented |

Recruited Athlete |

||||

|

Yes |

|

NS |

|

|

No |

|

NS |

|

Would still attended this college if different coach? |

||||

|

Very likely |

|

NS |

|

|

Likely |

|

NS |

|

|

Somewhat likely |

|

NS |

|

|

Somewhat unlikely |

|

NS |

|

|

Unlikely |

|

NS |

|

|

Very unlikely |

8.99 |

0.002 |

AS overrepresented |

Gender |

||||

|

Female |

5.41 |

0.02 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Male |

|

NS |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

||||

|

White, non-Hispanic |

27.74 |

0.000 |

AS underrepresented |

|

African American |

36.60 |

0.000 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Other |

12.62 |

0.000 |

AS overrepresented |

Father’s Educational Level |

||||

|

No HS |

39.15 |

0.000 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Completed HS |

27.02 |

0.000 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Attended college no degree |

|

NS |

|

|

Associate’s degree |

|

NS |

|

|

Bachelor’s degree |

21.98 |

0.000 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Master’s degree |

24.11 |

0.000 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Doctoral degree |

15.26 |

0.000 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Don’t know |

6.73 |

0.009 |

AS overrepresented |

Mother’s Educational Level |

||||

|

No HS |

42.98 |

0.000 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Completed HS |

28.51 |

0.000 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Attended college no degree |

10.83 |

0.001 |

AS overrepresented |

|

Associate’s degree |

|

NS |

|

|

Bachelor’s degree |

35.63 |

0.000 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Master’s degree |

19.94 |

0.000 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Doctoral degree |

4.21 |

0.040 |

AS underrepresented |

|

Don’t know |

3.98 |

0.046 |

AS overrepresented |

1 The calculated value of chi-square is corrected for continuity. |

||||

The findings indicated that athlete-students were overrepresented in the following groups:

- men’s basketball and football squads;

- athletes who receive full athletic aid;

- students who indicate that they would have been “very unlikely” to attend their current university or college under a different coach;

- African American athletes and those who identify as “other;”

- those whose fathers have very little education (no high school or high school graduate) or when the responded did not know their fathers’ level of education; and those whose mothers have very little education (no high school, high school graduate, or some college) or when the responded did not know their mothers’ level of education.

On the contrary, the results suggested that athlete-students were underrepresented in these groups:

- men’s lacrosse, women’s ice hockey, and women’s tennis teams;

- those who receive no aid or receive a partial scholarship;

- female athletes;

- white, non-Hispanic athletes; and

- students whose parents earned a bachelor’s or an advanced degree.

The distribution of athlete-students and student-athletes across attributes of three of the ten control variables did not differ significantly from the overall population. Specifically, we found no significant differences when we examined academic class, level of participation on team, or whether or not the student was recruited.

Table 2 provides the results of two different analyses – the direct effects and the total effects. The direct effects are estimated from the multivariate logistic regressions, adjusting for the control variables and the total effects are estimated from a univariate logistic regression that did not include the control variables from the model. This allowed for a comparison of the effects of the control variables on the particular relationship under investigation. The results suggested that student-athletes and athlete-students varied on a number of the measured dimensions which are outlined below as they relate to the 10 research questions.

Table 2 Student-athletes and athlete-students varied on a number of the measured dimensions |

||||||

Research Question |

Dependent Variable |

Total Effect 1 |

Direct Effect 2 |

Interpretation of significant direct effects |

||

|

|

beta |

p value |

beta |

p value |

|

1 |

Effect of athletics participation on university, major, and class selection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Reason for attending current college/university |

-0.5191 |

<.0001 |

-0.3417 |

0.004 |

AS think less about academics when choosing a college |

|

Major selection |

-0.4973 |

0.0002 |

-0.3404 |

0.0204 |

AS less likely to major in mathematics and science |

|

Reason for choosing your major |

-0.3837 |

<.0001 |

-0.3469 |

<.0001 |

AS less likely to select major to prepare for graduate study or a desired career |

|

Has athletics prevented you from majoring in what you want |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Have your coaches or others discouraged you from choosing a major |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Has athletics prevented you from taking courses you want |

separation |

|

separation |

|

|

|

Have your coaches or others discouraged you from taking certain classes |

separation |

|

separation |

|

|

|

Have your coaches or others discouraged you from extracurricular activity |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

2 |

Effect of athletics participation on GPA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

GPA |

0.6456 |

<.0001 |

0.3984 |

<.0001 |

AS have lower GPA |

|

Do you believe that athletics has affected your GPA? |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

3 |

Class participation and preparation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

participate actively in class |

0.2646 |

0.0008 |

0.2405 |

0.0068 |

AS less likely to participate in class |

|

come to class without completing reading assignments |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

come to class without completing writing assignments |

0.3705 |

0.0004 |

NS |

|

|

|

discuss issues or ideas outside of class |

0.1847 |

0.0099 |

0.2122 |

0.0088 |

AS less likely to discuss outside of class |

|

discuss ideas, grades, assignments with professor |

NS |

|

0.1654 |

0.0421 |

AS less likely to discuss with professors |

|

work with classmates on group projects |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

read non-assigned books for pleasure outside of class |

0.3422 |

<.0001 |

0.2681 |

0.0029 |

AS less likely to read books for pleasure |

4 |

Participation in intensive academic experiences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

research project |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

internship |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

study abroad |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

work with faculty member on independent study |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

senior thesis |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

5 |

Participation in extracurricular activities & campus events |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Performance or fine arts groups |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Religious organizations |

0.209 |

0.0083 |

0.2259 |

0.0131 |

AS are less likely to be involved with religious groups |

|

Fraternity or sorority |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Student government or university service |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Academic groups |

0.5044 |

<.0001 |

0.5166 |

<.0001 |

AS less likely to be involved with academic groups |

|

Publications or media groups |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Intramural or club sports |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Recreation or hobby groups |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Culture specific groups |

-0.3249 |

0.0034 |

NS |

|

|

|

concerts |

-0.336 |

0.0001 |

-0.2931 |

0.0034 |

AS less likely to attend concerts |

|

plays |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

speakers |

-0.4127 |

<.0001 |

-0.4111 |

0.0002 |

AS less likely to attend speakers |

|

art exhibits |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

sporting events |

-0.4455 |

<.0001 |

-0.3195 |

0.0118 |

AS less likely to attend sporting events |

6 |

Degree to which college contributes to personal growth & development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

leadership skills |

-0.5177 |

0.0069 |

separation |

|

|

|

teamwork |

-0.5871 |

0.0027 |

separation |

|

|

|

understanding of people of other races or backgrounds |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

study skills |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

time management |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

work ethic |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

sensitivity to members of opposite sex |

-0.2892 |

0.0277 |

NS |

|

|

|

ability to take responsibility for yourself |

-0.513 |

0.0453 |

NS |

|

|

7 |

Student vs. athlete perceptions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

view myself as more of an athlete than a student |

0.4807 |

<.0001 |

0.4219 |

<.0001 |

AS more likely to ses themselves more of an athlete than a student |

|

other students view me more as an athlete than a student |

0.3784 |

0.0004 |

0.3001 |

0.0136 |

AS more likely to see other students viewing them as athletes more than students |

|

professors view me more as an athlete than a student |

0.23 |

0.004 |

NS |

|

|

|

I spend more time thinking about athletics than academics |

0.2262 |

0.0053 |

NS |

|

|

|

I feel some professors discriminate against me as an athlete |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

I feel some professors favor me as an athlete |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

I feel some students treat me well as an athlete |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

I feel some students treat me poorly as an athlete |

NS |

|

NS |

|

|

|

Willing to sacrifice athletics participation for academics |

1.3447 |

<.0001 |

1.3902 |

<.0001 |

AS are less willing to sacrifice athletics participation for academics |

8 |

Perception of academic experience |

|

|

|

|

|

|

efforts you have made in classes |

0.4073 |

<.0001 |

0.3905 |

0.0003 |

AS feel less positive about their efforts |

|

relationships with faculty |

0.2757 |

0.0023 |

NS |

|

|

|

ability to succeed academically |

0.3586 |

0.0009 |

NS |

|

|

|

overall academic experience |

0.3291 |

0.0011 |

NS |

|

|

9 |

Importance of graduation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

to you |

0.9556 |

<.0001 |

0.9783 |

<.0001 |

AS feel their graduation is less important to them |

|

to your family |

0.5441 |

0.0008 |

0.5424 |

0.0028 |

AS feel their graduation is less important to their family |

|

to your coach |

0.2761 |

0.0134 |

NS |

|

|

10 |

Future Goals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Likelihood of going pro |

-0.6324 |

<.0001 |

-0.2674 |

0.0022 |

AS believe going pro is more likely |

|

Plans for first year out of college |

-0.5428 |

<.0001 |

-0.5153 |

<.0001 |

AS more likely to devote time to their sport |

|

Likelihood of attending graduate school |

0.9205 |

<.0001 |

0.7927 |

<.0001 |

AS believe graduate school to be less likely |

|

Likelihood of having a career in athletics |

-0.3498 |

<.0001 |

-0.2368 |

0.0053 |

AS believe it is more likely career will involve athletics |

|

How important is making lots of money |

-0.2022 |

0.0134 |

NS |

|

|

1 Total effects estimated from a univariate logistic regression which drops all of the control variables from the model. This is equivalent to a two-way contingency table of response variable by grouping variable |

||||||

2 Direct effects estimated from the multivariate logistic regressions, adjusting for control variables |

||||||

The results provide partial support for the first research question: “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to whether or not athletics participation influenced university/college choice, major choice, and class selection?” Specifically, there were significant differences on three of the eight measures. Athlete-students think less about academics when choosing a college, were less likely to major in math and science, and were less likely to select a major because if interest in the field or to prepare for graduate school.

The second research question was “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their GPA?” The results indicated that athlete-students had lower GPAs than student-athletes. There was no difference between the groups in terms of their belief that participation in athletics affected their GPA.

We used seven items from the GOALS survey to capture class participation and preparation as stated in our third research question: “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their class participation and preparation?” We found significant differences in four of those measures. Specifically, athlete-students were less likely to participate in class, discuss issues or ideas outside of class, have discussions with professors, and to read books for pleasure outside of class.

Our analyses did not reveal any differences between student-athletes and athlete-students with respect to the fourth research question: “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their involvement in intensive academic experiences?” Student-athletes and athlete-students took part in research projects, internships, study abroad, independent studies, and senior theses at roughly the same rate.

Fourteen separate GOALS items were used to address the fifth research question, “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their level of participation in extracurricular activities and campus events?” There were significant differences between student-athletes and athlete-students on five of those measures. Specifically, athlete-students were less likely than their student-athlete counterparts to be involved with religious groups or academic groups and they were less likely to attend concerts, attend speakers’ forums, or sporting events.

We used eight GOALS items to address the sixth research question, “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to the degree to which college contributed to their personal growth and development” and found no significant difference between the groups. Student-athletes and athlete-students believed that college contributed to their leadership skills, teamwork, understanding of other people, study skills, time management, work ethic, sensitivity to members of the opposite sex and their ability to take responsibility of themselves. Very few of either group reported that college had negative or very negative effects on these skills.

The seventh research question was, “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to whether they consider themselves more of an athlete than a student?” and we used nine GOALS items. We found significant differences between the two groups on three of the measures. Specifically, athlete-students were more likely to identify as an athlete than a student, were more likely to believe that other students view them as an athlete rather than a student, and were less willing to sacrifice athletics participation for academics.

The eighth research question was “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their perception of their academic experience?” We found significant results for one of the four items; athlete-students felt less positive than did student-athletes about the efforts they made in their classes.

We used three GOALS items to address the ninth research question: “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to how important graduation is to them?” We found that graduation was less important to athlete-students and their families than it was for student-athletes and their families.

The final research question was, “Do student-athletes differ from athlete-students with respect to their future goals,” and we used five GOALS items. Four of the five yielded significant results; athlete-students were more likely to believe they will play professional sports or that they will have a career in athletics. They were more likely to devote themselves to their sport during their first year out of college and were less likely to plan to attend graduate school.

Taken collectively, we are able to answer in the affirmative to eight of the ten proposed research questions; yes, student-athletes and athlete-students differ significantly on a number of important dimensions including school and major selection, GPA, class participation, participation in extracurricular activities, self-perceptions, and importance of graduation, and plans for the future. We found no differences across the two groups in terms of their participation in intensive academic experiences or in the degree to which college had contributed to their personal growth and development.

DISCUSSION

We examined two groups of Division I student athletes, those who would not have attended a university had it not been for their athletic talents (athlete-students) and those who were university bound regardless of their athletic ability (student-athletes). The results revealed that these two groups varied significantly in ways related to their future goals, how they selected a major, experience in college, self-identify, value of graduation, and perceived benefits of college. From a demographic standpoint, athlete-students were more likely to be students of color and more likely to have parents who did not attend college. From an athletic standpoint, they were overrepresented among men’s basketball and football athletes and among those on full athletic aid.

Our results provide quantitative evidence that is consistent with some of the journalistic and anecdotal accounts of the dismal academic performance of some student athletes, especially those on men’s basketball and football teams (30). Our findings are also consistent with several reports of the growing disparity in academic preparation between athletes of color and their white counterparts (11, 19, and 22). They also confirm the intergenerational nature of higher education (5); parents who have earned a college degree or an advanced degree, compared to those who have not, are more likely to expect their children to attend college.

While this study focused on athletes, the critique focuses on policies. We do not intend to blame or stigmatize the athlete-students in our sample. As Bowen (3) and his colleagues assert, “students who excel in sports have done absolutely nothing wrong, and they certainly do not deserve to be “demonized” for having followed the signals given to them by coaches, their parents, admissions officers, and admiring fans” (p. 12). We have demonstrated here that a small segment of the Division I student-athlete population (our athlete-students) had a very different university experience than did their student-athlete peers. Consequently, it is incumbent upon institutions to implement policies, programs, and processes that focus on the roughly ten percent of their student athlete population who may not be enjoying the spectrum of opportunities offered by the university experience. Universities should tailor extra support and guidance to the needs of “high-risk” athlete-students who compete in men’s basketball and football and to those students whose parents did not attend college. According to the results of this study, these students are most at risk of failing to enjoy the full benefit of their university experience. As Van Rheenen (28) eloquently stated, “Institutions face a crisis of conscience when educational opportunities are offered to certain students based primarily on their athletic ability, especially when these opportunities are perceived as disingenuous due to the academic preparation and demanding athletic commitments of these recruited college athletes” (p. 550). Consequently, if institutions are going to continue to allow such students admission, it is incumbent upon athletic administrators and coaches to be forthright with recruits, to uphold their institutions’ academic mission, and to provide high-risk athlete-students with an enhanced array of academic and social supports.

On the other hand, the results of this study also confirm that the vast majority of students (89.3%) who compete in Division I athletics are, indeed, “student-athletes” whose participation in their sport is a component of their overall university experience. To borrow from the NCAA’s own tagline: they go pro in something other than their sport. This is good news for college sports overall and a big success for the NCAA’s “academics first” mission.

Even those for whom academics is a secondary consideration, the benefits of attending a university have been well-documented (1). Individuals who attend enjoy a wide range of personal, emotional, financial benefits not enjoyed by those who did not attend. Consequently, one could certainly make the argument that any time spent at a university, even if it is a short time and even if the student does not ultimately graduate, will benefit that student. As stated by one long-time college athletics professional, “After going to college, even if you don’t graduate, you will be better off than you were when you got here” (C. Masner, personal communication, March 21, 2017). Even the 7-18 % of revenue sport athletes who are reading at an elementary school level, as found by Ganim (8), will improve while they are in school.

Study Limitations

Our data were collected in 2006, three years after the institution of the Academic Progress Report (APR). The APR was designed to improve the academic performance of student athletes and all indications suggest that is has done just that (21). Consequently, it is possible that the results of our research, if replicated with more current data, would result in different results. We encourage future researchers to reexamine our research questions using the 2015 GOALS data.

CONCLUSION

Overall, the results of this study offer support for the claim that participation in athletics provides a gateway to a 4-year university for students who would not have otherwise attended. Despite the oft publicized failures of some student-athletes in some the high profile sports, the current research reveals that in most sports, across Division I, athlete students do succeed and do gain the full benefit of a university experience in ways that are on par with their student-athlete peers. Our results provide coaches, faculty athletics representatives, athletic administrators, and admissions officers with the evidence to either support, or not, coaches’ requests to specially admit students who may not be able to gain access to the institution based on their academic record alone, or students who for other reasons do not self-identify as being university-bound.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

Despite

the controversies surrounding perceived student-athlete exploitation, the

achievement gap, and poor academic performance of some student athletes, many

still believe that athletics enhances the academic mission of universities (14).

Intercollegiate athletics help to build a sense of community; strengthen the

values of integrity, teamwork and hard work; and provide an important link to

larger community (6, 14). It also teaches student-athletes invaluable skills

that they take with them into the work world including time-management,

integrity, and teamwork (14). It is the responsibility of member institutions

to provide that small group of “athlete-students” with the extra support they

need so they, too, can experience the full range of benefits available to university

students.

REFERENCES

- Baum S., Ma J. & Payea K (2010). Education pays: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. College Board Advocacy and Policy Center

- Bimper, A. (2013, May 2). Kansas State scholar examines the classroom experiences of black student athletes. The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. Retrieved June 11, 2016, from https://www.jbhe.com/2013/05/kansas-state-scholar-examines-the-classroom-experiences-of-black-student-athletes/

- Bowen, W. G., & Levin, S. A. (2003). Reclaiming the game: College sports and educational values. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Branch, T. (2011, October). The shame of college sports. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/10/the-shame-of-college-sports/308643/

- Brownstein, R. (April 11, 2014). Are college degrees inherited: Parents’ experiences with education strongly influence what their children do after high school. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2014/04/are-college-degrees-inherited/360532/

- Comeaux, E., & Harrison, C. K. (2011). A conceptual model of academic success for student-athletes. Educational Researcher, 40(5), 235-245. doi: 10.3102/0013189×11415260

- Eichelberger, C., & Levinson, M. (2007, October 29). College football powers prove academic bonus payments worthless. Bloomberg News. Retrieved from http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aNlcBVGQ.jb4

- Ganim, S. (2014, January 8). CNN analysis: Some college athletes play like adults, read like 5th-graders. Retrieved July 15, 2016, from http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/07/us/ncaa-athletes-reading-scores/index.html

- Gravetter, F. J. & Wallnau, L.B. (2013). Essentials of statistics for behavioral sciences. (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Gup, T. (1989, April 4). FOUL! How the national obsession with winning and moneymaking is turning big-time college sports into an educational scandal that, for too many players,

- leads down a one-way path to broken dreams. Time Magazine. Retrieved from:

- http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.csulb.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=7&sid=fe5bdf50-83ed-4291-afc5-d4f617fb55bd%40sessionmgr2&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#AN=57898430&db=a9h

- Harper, S. (2016). Black male student-athletes and racial inequities in NCAA Division IO college

- sports. (2016). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Center for the Study of Race & Equity in Education. Retrieved from: http://nepc.colorado.edu/files/publications/Harper_Sports_2016.pdf

- Harrell, F. E. (2001). Regression modeling strategies: With applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer.

- Hildenbrand, K., Sanders, J., Leslie-Toogood, A., & Benton, S. (2009). Athletic status and academic performance and persistence at a NCAA Division I university. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 3(1), 41-58.

- Holbrook, K. A. (2004, winter). Jumping through hoops: Can athletics enhance the academic mission. The Presidency, 7(1), 24-31.

- Huber, K. (2013, July 22). Castillo runs to new heights after completing Willamette career: Former bearcat balances work and athletic competition. Retrieved from https://www.willamette.edu/athletics/news/archive/2013/07/22_ATHL_Castillo_Feature.php

- Knight Foundation (2001). A call to action: Reconnecting college sports and higher education. Retrieved from: http://www.knightcommission.org/images/pdfs/2001_knight_report.pd

- Knight Foundation (1999). Reports of the Knight Foundation on intercollegiate athletics (1991-1993). Retrieved from: http://www.knightcommission.org/images/pdfs/1991-93_kcia_report.pdf

- Knobler, M. (2008, December 30). Public university athletes score far below classmates on SATs. Retrieved June 28, 2016, from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/education/2008-12-30-athletes-sats_n.htm

- Lapchick, R., Marfatia, S., Taylor-Chase, T., Cotta, T., & Morrison, E. (2016). Keeping score when it counts: Assessing the academic records of the 2016-2017 bowl-bound college football teams. The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport. Retrieved from: http://nebula.wsimg.com/13533ce46b93ecad13c6a8304c43868f?AccessKeyId=DAC3A56D8FB782449D2A&disposition=0&alloworigin=1

- National Collegiate Athletic Association. (2016). NCAA Division I Manual August 2016-2017. Indianapolis, Indiana.

- Paskus, T. (2012). A summary and commentary on the quantitative results of current NCAA academic reforms. Journal of Intercollegiate Sport, 5(1), 41-53.

- Potuto, J. R., & O’Hanlon, J. (2007). National Study of student –athletes regarding their experiences as college students. College Student Journal, 41(4), 947-966.

- Price, J. A. (2009). The effects of higher admission standards on NCAA student-athletes: An analysis of proposition 16. Journal of Sports Economics, 11(4), 363-382. doi: 10.1177/1527002509347989

- Shuman, M. P. (2009). Academic, athletic, and career athletic motivation as predictors of academic performance in student athletes at a Division I university. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC.

- Simons, H. D., & Van Rheenen, D. (2000). Noncognitive predictors of student athletes’ academic

- performance. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 30(2), 167-181.

- doi:10.1080/10790195.2000.10850094

- Smith, R. K. (2000, Fall). A brief history of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s role in

- regulating intercollegiate athletics Retrieved June 9, 2016, from:

- http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1393&context=sportslaw

- Ting, S. R. (2009). Impact of noncognitive factors on first-year academic performance and persistence of NCAA Division I student athletes. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development, 48(2), 215-228. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1939.2009.tb00079.x

- Van Rheenen, D. (2012). Exploitation in college sports: Race, revenue, and educational reward. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 48(5), 550-571. Doi: 10.1177/1012690212450218

- Wallau, R. (2014) Schlissel talks athletic culture and academic performance issues. The Michigan Daily. Retrieved July 19, 2016 from https://www.michigandaily.com/article/schlissel-talks-athletics-and-administration-sacua

- Wolverton, B. (2012, June). The education of Dasmine Cathey. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/The-Education-of-Dasmine-Cathey/132065/

[i] Five hundred and ninety three (593) students did not respond to this question and are, therefore, excluded from the analyses.