Authors: Jennifer Willett, Chris Brown, & Bernie Goldfine

Corresponding Author:

Jennifer Willett, Ph.D.

Kennesaw State University

520 Parliament Garden Way NW

Kennesaw, GA 30144

jbeck@kennesaw.edu

470-578-6486

Jennifer Willett is an Associate Professor in the Department of Exercise Science and Sport

Management at Kennesaw State University.

Christopher Brown is an Associate Professor in the Department of Exercise Science and Sport

Management at Kennesaw State University.

Bernie Goldfine is a Professor and the Physical Activities Coordinator in the Department of

Health Promotion and Physical Education at Kennesaw State University.

ABSTRACT

With an increasing amount of sport management master’s programs being created within the U.S. and internationally, little seems to be known about their curriculum and overall structure. A total of 194 sport management master’s programs from the United States were examined on curricular and accreditation standards based on COSMA accreditation and the Common Professional Component (CPC). Data was collected from school websites and results varied and ultimately showed that curriculum is different, indicating that sport management master’s programs do not necessarily follow a specific program model. Results suggest that the examination of graduate curriculum should support the notion that program curriculum needs to evolve through the work of all parties (institutions, practitioners, industry) involved.

Keywords: Sport Management, Master’s Programs, Curriculum, Accreditation

INTRODUCTION

The academic field of sport management has grown tremendously in a relatively short amount of time (Ferris & Perrewe, 2014). Since the 1960s, sport management programs in the United States have witnessed substantial growth and increasing popularity due to enormous student interest (Jones, Brooks & Mak, 2008). With tremendous growth comes progress, and ultimately, more analysis. As the sport management discipline continues to grow and expand inside and outside of the U.S., examining programs more in-depth is the next logical step in the evolution and growth of sport management as an academic discipline.

Jones et al. (2008) suggested that the evolution of sport management programs in the United States has moved from the physical education model to a more business-oriented model. The move to a more business model approach can be seen in the tremendous growth and expansion of graduate programs in recent years. According to NASSM (2017), sport management master’s programs are now offered in over 220 U.S. and over 40 international institutions. With the growth of sport management programs, specifically at the master’s level, more scrutiny is beginning to be paid to the overall structure of the programs and the curriculum being used within these programs. There is a need to develop sound curricular guidelines to integrate the needs of the student and the needs of the sport business organization (Kelley, Beitel, DeSensi & Blanton, 1994).

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

The various research regarding sport management graduate programs and curriculum raise many questions for sport management educators. Specifically, what are current sport management master’s programs providing to students? Students enter sport management master’s programs for a variety of reasons, not the least of which have to do with potential jobs after graduation. As graduate students continue to enroll in sport management programs, it is necessary that programs continue to explore not only how to best serve their students’ varied interests at the graduate level, but also how to differentiate themselves from other programs.

In an attempt to examine sport management master’s programs, which begins with a better understanding of the graduate curriculum, the researchers examined master’s programs at 4-year institutions. The purposes of this study was to: (1) provide an overview of the graduate programs within sport management, specifically master’s programs; and (2) provide a snapshot of sport management master’s programs based on COSMA accreditation and the Common Professional Component (CPC). However, according to COSMA (2015b), only 14 schools have accredited master’s programs. This suggests that at the graduate level, programs may have used other accreditation standards from another entity based on where the program is housed (i.e. business) or are just not following COSMA recommendations.

Program Accreditation and Development

There are over 400 sport management programs at the undergraduate and graduate level recognized by the North American Society for Sport Management in the U.S. (NASSM, 2017), and with the abundance of professional, collegiate, high school, and youth sports, it is no surprise that sport management education continues to be a growing area of interest. Early on in the field of study, Slack (1991) discussed several problems that still exist at the graduate level today. Students are taking fewer courses than at the undergraduate level and they usually have a research component, therefore students are not gaining the needed practical knowledge to be successful. In addition, Slack (1991) also cited the issue of one to two faculty teaching all of the required graduate courses, which does not allow for any area of depth.

As sport management programs grow and continue to graduate students, the nature and scope of the curriculum used within these programs has gained increased analysis. It is becoming more important to understand curriculum and accreditation requirements. Accreditation is needed to prevent the proliferation of diploma mills and provide external accountability of quality of education at legitimate educational institutions (Yiamouyiannis, Bower, Williams, Gentile & Alderman, 2013). In 1989, the Sport Management Program Review Committee (SMPRC) was developed to “approve” programs using the National Association for Sport and Physical Education-North American Society for Sport Management (NASPE-NASSM) standards, and in 2008, the SMPRC was replaced by the Commission on Sport Management Accreditation (COSMA), a formal accrediting body. COSMA’s purpose is “to promote and recognize excellence in sport management education in colleges and universities at the baccalaureate and graduate levels through specialized accreditation” (COSMA, 2015a, p. 1).

COSMA has identified twelve core areas Common Professional Component (CPC) topical areas that undergraduate sport management students need to master and sport management programs need to address within the curriculum. The CPC topical areas are as follows: Social, Psychological and International Foundations of Sport; Sport Management Principles; Sport Leadership; Sport Operations Management; Sport Governance; Ethics in Sport Management; Sport Marketing and Communication; Sport Finance; Accounting; Economics of Sport; Legal Aspects of Sport, and Integrative Experiences.

According to COSMA (2015a), the CPC requirement does not apply to master’s degree and doctoral programs. However, master’s degree programs in sport management should require a minimum of 30 semester credit hours (45 quarter hours) of graduate level work. In addition, COSMA requires that courses should be beyond the level of the undergraduate CPC courses, as well as recommending at least 50% of the course work in the graduate program should be offered by the academic unit/sport management program.

Sport Management Master’s Programs

One of the first comprehensive studies on sport management graduate education by Kelley et al. (1994), suggested the content of the graduate sport management program should be based on two factors: (a) the experience, degree content and background of the student upon entry to the graduate program; and (b) the focus, emphasis and specificity of professional requirements for the positions related to the graduate student’s career goals. The emphasis of the graduate program curriculum should be to help students move from where they are to where they want to be, while at the same time to maintain the integrity of the nature of graduate study in sport management (Kelley et al., 1994). In addition, the components of the graduate curricular model should be focused toward attainment of entry-level administrative positions in the student’s area of interest and should include (a) the professional core, (b) selected professional courses, (c) research techniques, (d) internship experiences, and a thesis or project (Kelley et al., 1994). The professional core should include courses from (a) advanced levels of sport administration theory and (b) advanced levels of sociocultural aspects of sport (Kelley et al., 1994). Kelley et al. also suggested that individuals with graduate degrees would be prepared to accept positions at the managerial level.

Tungjaroenchai (2000) compared eleven sport management programs in the southern U.S. at the master’s degree level and found that the most common degree offered was as Master of Science Degree (M.S.) and required 36 credit hours. Tungjaroenchai revealed that it was common to offer 6-8 required courses in the core curriculum and the primary culminating experiences consisted of internship or practicum. However, most programs did offer the option of writing a thesis.

METHODS

The researchers first started by collecting primary data from the schools websites. Websites were chosen because they provide an efficient manner in which to access the numerous sport management master’s programs in the United States. Websites are one of the written communication sources for content analysis (Marshall & Rossman, 1999). To begin, all master’s programs from the United States listed on the NASSM website were identified and analyzed. As an important footnote, the sample for this study and the information collected were limited to only schools listed on NASSM’s website and the schools websites themselves. Even after being identified through NASSM, some schools had to be excluded from the study for various reasons, including incomplete information, link no longer working, and outdated information.

Two researchers visited 272 universities website to gather information on each program from January 2015 to May 2015. To ensure validity and reliability of the data and the data collection process, both researchers coded data individually and then collaborated and revisited the information together to verify and edit any discrepancies. In the circumstance that the researchers could not come to a similar decision, the school was eliminated from the data set. Program information was collected along with the Common Professional Component (CPC) recommended by COSMA. In addition, if a program required a research methods or statistics course, it was coded in one category as seen below. Researchers coded the number of required courses for each CPC content area and other courses required but not in the CPC. Elective courses were not coded as they varied drastically from program to program. See data collection categories below.

Data Collection Categories:

- School

- Region

- Delivery

- Minimum Required Credits

- Core Credits

- Name

- Concentration

- COSMA Accreditation

- Common Professional Components (CPC)

- Social, psychological and international foundations of sport

- Management

- Ethics in sport management

- Sport Marketing & Communication

- Finance/Accounting/Economics

- Legal aspects of sport

- Integrative Experience

- Research/Statistics

- Number of other required courses not in the CPC

As of 2015 there were 272 Master’s programs listed on the NASSM website, 223 from the U.S. and 49 international (NASSM, 2015). After following the systematic procedures listed above, the data set consisted of 194 usable programs (N =194). MBA and JD programs with a specialization in sport management were excluded when comparing CPC curriculum because required core courses were business-related/law related and sport-related courses were considered electives. In addition, the researchers only coded sport management programs, and as a result some listed on the NASSM website were deleted from data collection (coaching, sport psychology, hospitality and tourism management, recreation and leisure studies). Some schools offered similar online and on-ground programs thus the researchers coded the on-ground program once. Several schools listed an array of courses and students were able to select their program of study, therefore, they were eliminated from the data set. At the master’s level it was very common for programs to offer a thesis and internship option. Since the majority of graduates in the field of sport management are hired based on experience levels and networking capabilities, the researchers coded the internship track.

As previously noted, this study was limited to only schools listed on the NASSM website and those with adequate information available. Furthermore, several schools were excluded due to inadequate information. Additionally, the researchers only used COSMA’s CPC components as the baseline for coding categories, therefore any course not listed was coded as other and there was no way to identify the specific subject area.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Master’s Programs

Sport management master’s programs (N= 194) in the U.S. were first compared in terms of (a) program delivery, (b) degree name, (c) whether it was a concentration or standalone program (d) accreditation status, and (e) total credit hours. Across the region most programs (84.6%) were offered on campus however, there were twenty-two programs (11.3%) that did offer online education and 2.6% had programs both online and on campus. The degree name that was most popular was “Masters of Science” (49.2%) followed by “Masters of Arts” (21.5%). Just over 14% were listed as “Masters of Business Administration” and 14% were considered other and had specific names like “Masters of Sports Administration.” Fifty-four percent of the programs listed their sport management master’s program as a concentration compared to a standalone program. With accreditation still in its infancy, the majority of programs (85.1%) were not COSMA accredited. In regards to program length and total credit hours, the mean of programs offered was 35 credit hours but several programs did have more than that total with the highest at 61 credit hours.

Curriculum Examination Using COSMA Common Professional Component (CPC)

To compare curriculum of sport management programs at the master’s level, the researchers used COSMA’s common professional component (CPC). According to COSMA (2015b), “excellence in sport management education at the undergraduate level requires coverage of the key content areas of the sport management field” (p. 1). The requirement that the graduate courses be beyond the level of the undergraduate CPC courses means that the courses should be graduate level, advanced courses in sport management (COSMAa, 2015). The content suggested by COSMA include seven main areas. In addition to these areas, the researchers added another area that encompasses a research component. Given the nature of graduate programs and the importance that scholarly work plays in successful completion of a sport management graduate program, a research category was added so that the researchers could also examine the importance of research methods and statistics at the graduate level. Any class that was listed as research methods or statistics was coded in this area. Lastly, there were many courses required that did not fit into one of the above categories so they were coded as other.

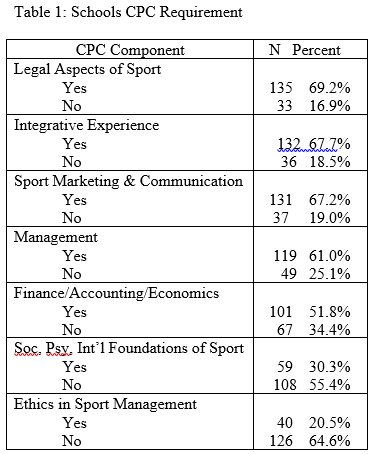

Across the U.S., legal aspects of sport (69.2%) was the most common CPC component required while ethics (20.5%) was the least common CPC component. See Table 1 for the ranking order from most common to least common CPC components required by U.S. programs offering a master’s degree in sport management. Based on the data, over 50% of all programs believed that 5 components of the CPC were vital to the curriculum in their master’s program (legal aspects of sport, integrative experience, marketing/communications, management, and finance/accounting/economics). Out of the different courses COSMA listed under management, the most common course offered in this area was event/venue management/operations. When breaking down the CPC area of finance/accounting/economics, the most common course offered was related to sport finance. In the integrative experience CPC, the most common offering was internship. However, 32.3% did not require an internship at the Master’s level. When internship was required, it was usually listed as 1-3 credit hours (30.8%) followed by 4-6 credit hours (19.0%) and 7-9 credit hours (2.1%). Additionally, 61.6% required 1-2 courses in research however, 23.1% did not require a research or statistical based course. In terms of other courses required outside of the CPC components, the highest was one course at 12.8% followed by zero courses (7.7%) and 2 courses (7.2%). As a result, most programs based their curriculum on COSMA’s CPC components.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The purpose of this study was to: (1) provide an overview of Master’s programs within sport management; and (2) provide a snapshot of curriculum within sport management master’s programs based on COSMA accreditation and the Common Professional Components (CPC).

When reviewing the characteristics of master’s programs, the manuscript highlights some important data such as delivery method and program length. With institutions looking to expand their brands, only having 11% of programs reporting that they deliver their graduate degree on-line is surprising. Because many students are working full-time and are deciding to come back to graduate school in the sports industry, having full time, online education is an efficient and effective manner to reach those students. However, the data does show that numerous programs offered both an on campus and online option for their master’s program. We should surmise that that number will increase exponentially in the near future. Furthermore, the average number of credit hours required for a master’s in sport management was 35. This is one credit hour less than Tungjaroenchai (2000) found when surveying programs in the southern U.S.

While the degree conferred (M.S., M.A., M.Ed, MBA) has been reported, the title or concentration name provides a unique perspective on the programs goals and objectives. For example, a small number of programs included “Intercollegiate Athletics,” “Athletic Administration.” or “Leadership” in their title. “Sport & Entertainment Management” and “Sport Venue & Event Management” were also used within program titles. More specific degree names may help attract students to programs. However, data revealed that many programs are considered concentrations and not stand alone programs. Therefore, they are forced into common degree / programs titles, such as “Masters of Arts” or “Masters of Science,” which accounts for 70% of the programs within the study.

Another highlight within program characteristics relates to the number of programs that reported to be a concentration (54%), compared to a standalone degree. Given that in many ways master’s programs in sport management are still in their infancy, the ease of adding a concentration to an existing graduate degree (ex. Exercise Science, Kinesiology) makes sense. Oftentimes a concentration is a more fiscally responsible method of creating a graduate program. In addition, offering a concentration can also eliminate the tedious process of creating a new graduate degree. Some states (e.g. Georgia) now require that new programs meet specific guidelines tied to economic impact, university and state educational goals, etc. In addition, the creation of a new graduate degree traditionally creates increased fiscal and workload responsibilities. Oftentimes additional graduate faculty need to be hired and a graduate coordinator needs to be appointed. This may be somewhat difficult for smaller schools and programs located outside of large cities.

As it relates to graduation, research suggested that a variety of requirements exists among programs. For example, of the programs reviewed for this study, there were three main options as a graduation requirement: thesis or non-thesis option, thesis or comprehensive exam option, and thesis or internship option. In addition, there were also other graduation requirements listed by each program, which included a project or field experience requirement, colloquium, internship or project, a thesis only requirement and an independent study only requirement. The variation can be attributed to the type of school (research, comprehensive, teaching, etc.), type of program, program needs and goals, and resources. Students entering graduate programs should make sure they do their research and find the best fit for their future goals and aspirations.

The research results also indicated that only 7% of programs have attained COSMA Accreditation, and there could be various reasons for that small of a percentage. Fielding, Pitts and Miller (1991) stated that many reasons why institutions do not seek accreditation is the “loss of flexibility, elitism, implementation costs, and increased program costs, also, many programs feel that the marketplace will function as an assessment mechanism” (p.12). In addition, Jones et al. (2008) noted that the need for approval may not be important to institutions because many have limited financial and human resources.

The only requirement the researchers found for master’s degree curriculum in the COSMA Accreditation Manual was that the graduate courses go beyond the level of the undergraduate CPC courses. Using COSMA’s common professional component (CPC) provided the researchers with the most valid instrument to examine curriculum among a broad and diverse group of sport management graduate programs. It also provided a great baseline to compare program curriculums. As with the program characteristics data, the curriculum comparison among programs also yielded some important information. Data showed that in the U.S., legal aspects of sport (69.2%) was the most common required course, with integrated experiences (67.7%), marketing, and communications very close at 67.2%. In many respects, legal aspects of sport being so prominent within the curriculum makes perfect sense. The possibility that a sport administrator could be a defendant in a sports related lawsuit has increased exponentially over the past few years. Given the importance of understanding legal issues and the increasing amount of litigation taking place within sports, the study of law within sport management programs has become a necessity. As a society, we are very litigious so a basic understanding of liability and negligence are an important component of any graduate student’s curriculum.

Interestingly, management was the fourth most popular requirement at 61% in the U.S. Although it was very close to the top three, one would think that the topical area in the fields name (Sport Management) would be required at a higher rate. When comparing the results to Eagleman and McNary (2010) which suggested the top required courses include introduction to sport management, sport psychology, sport organizational behavior and internship, only management and integrative experiences were similar. The CPC component for psychology/sociology/international sport ranked second to last at only 30% and was not close to being in the top four. This could be explained by the branching off of other programs where sport psychology is more common like coaching, kinesiology, etc.

It does seem evident that programs believe integrative experiences, especially internships, are vital to professional preparation programs at both the graduate and undergraduate levels as Williams (2003) found. Schoepfer & Dodds (2011) further supported the results as they found 77% of sport management programs at the bachelor’s, masters or doctoral level have an experiential learning requirement which was the most common curricular component. The bigger question is: Are the current sport management programs at the graduate level, more specifically the master’s level, offering the essential curriculum for success?

The findings of this study may assist with answering this question but they also bring up many other discussion points. COSMA only requires that master’s degree courses go beyond the level of undergraduate CPC courses. With only 7% of the programs accredited, one cannot conclude that this is occurring. It could be inferred that non-accredited sport management master’s programs are meeting this requirement, but there is no way to truly know unless they go through accreditation or a self-study process. In addition, MBA programs (14.4%) in the study do not require any sport management courses because their core curriculum is already standardized and follows Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) accreditation. Many of the MBA programs offered elective courses, which did offer sport related areas but with the requirements, students could only choose 2-3 courses to supplement the other business required courses. If a student did not have an undergraduate degree in sport management and completed a MBA with a concentration in sport management, would they have the necessary skills and knowledge to be successful in the sports field?

This brings up another issue of graduate education and the requirement of a research methods and/or statistical analysis course. Many programs offered the option of completing a thesis as a graduation requirement, so it is logical that student’s acquire the knowledge to carry out a research study from start to finish. Other proponents feel it necessary to expand beyond the undergraduate level knowledge and include such a requirement. Case (2003) pointed out the fact that the research component should reflect the needs of a sport management practitioner. While Slack (1991) discussed the fact that students are taking fewer classes at the graduate level and potentially not gaining the needed practical knowledge to be successful. This study revealed that 61.6% required 1-2 related courses however, 23.1% did not require a research or statistical based course. It could be surmised that the variation in research requirements is specifically determined by the type of institution (research, comprehensive, teaching, etc.), or the programs goals and objectives. Some students have goals of continuing their graduate education so that they can move into full time positions within higher education, necessitating a more researched focused curriculum. Other students are looking for more practical and applied classes, suggesting they are looking at graduate programs as a stepping stone within the industry. However, it could be argued that as graduates become more qualified and are hired into leadership positions, research or statistical based courses will be crucial to future success, regardless of students’ future interests.

CONCLUSION

The results of the current examination of sport management master’s programs within the U.S. indicate that there is not a common core of classes students take that provide uniformity among programs. While flexibility within curriculum, especially at the graduate level, provides advantages to the program and the student, the legitimacy of the knowledge and experienced gained can come into question.

Based on the current research and findings, and to support COSMA’s curriculum standards, it is the author’s opinion that a common body of knowledge be followed to better create a more uniformed approach to graduate sport management curriculum. While master’s programs in sport management are comparatively young, the variety of curriculum within programs is surprising. With such variety, it is difficult to determine the knowledge and experience students gain from attending a sport management master’s program. And without providing tangible knowledge and quantifiable experiences to graduate students through a common core curriculum, sport management graduate programs could be faced with declining student enrollment. For example, MBA programs are housed in AACSB accredited business schools that have specific curriculum requirements. Those curriculum requirements are known by industry professionals and provides those professionals with a baseline to accurately evaluate graduates and potential hires. It would seem to make sense that sport management graduate programs would want to provide its industry professionals with the same baseline.

It seems important that even if programs do not go through the accreditation process that they at least follow CPC recommendations. In addition, a separate section of goals, student learning outcomes, and measurement tools of the outcomes assessment plan should be provided for your master’s degree program that are specific and appropriate for assessment of the learning of master’s level students. These core courses, competencies or content should be the underpinning for which each graduate program is designed, while allowing for some diversification so that programs can differentiate themselves from their competitors.

Given that this study revealed only 7% of current master’s programs are accredited, and that accreditation is not a high priority for many programs, this puts the onus on potential students to thoroughly research a school’s curriculum and learning outcomes. In the end, student’s want to make sure that after completing a master’s degree they are prepared to take leadership positions. Current and future demand for graduate sport management programs will continue to mature and grow not only in the U.S., but internationally as well. It is imperative that sport management academics start the process to move graduate programs forward.

Moving forward, much more in depth research into sport management graduate programs is recommended, including a review of graduate programs characteristics, entrance and graduation requirements, as well as information on employment after graduation. In addition, future research should explore faculty and practitioners views on areas where students are lacking in the classroom and workplace. Surveying students in the workplace could also provide valuable information on the areas they are adequately and inadequately prepared for after graduation.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

This study’s application is more general in nature and suggests that a more developed set of core knowledge and skills be required across all sport management master’s programs. While the history of sport management master’s programs is moderately short, the variety of degree names and program curricula may muddle the understanding of sport management graduate programs by potential students, as well as by professionals in the field about what the degrees offer and what to expect of a person with such a degree. With a labor market that reflects more sport management graduates each year than job opportunities, it is important to equip new graduates with the skills, competencies and experiences needed to be competitive (Eagleman & McNary, 2010).

More specifically, for sport management to continue to develop as a field and be recognized by sport management professionals, it seems necessary to educate those hiring in the field to look more closely at employing graduates from accredited programs that meet a minimum core set of knowledge and skills. Additionally, it is imperative that institutions provide the best and most applicable sport management graduate curriculum in order for sport management students to become the best-qualified and most highly trained professionals possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

REFERENCES

1. Case, R. (2003). Sport management curriculum development: Issues and concerns. International Journal of Sport Management, 4, 224-239.

2. COSMA. (2015a). Commission on Sport Management Accreditation. Retrieved from: http://www.cosmaweb.org/

3. COSMA. (2015b). Commission on Sport Management Accreditation: About COSMA. Retrieved from: http://www.cosmaweb.org/list-of-accredited-programs2.html

4. Eagleman, A.N., & MCary, E.L. (2010). What are we teaching our students? A descriptive examination of the current status of undergraduate sport management curriculum in the United States. Sport Management Education Journal, 4(1), 1-18.

5. Ferris, G.R., & Perrewe, P.L. (2014). Development of sport management scholars through sequential experiential mentorship: Apprenticeship concepts in the professional training and development of academic. Sport Management Education Journal, 8, 71-74.

6. Fielding, L.W., Pitts, B.G., & Miller, L.K. (1991). Defining quality: Should educators in sport management programs be concerned about accreditation? Journal of Sport Management, 5, 1-17.

7. Jones, D.F., Brooks, D., & Mak, J. (2008). Examining sport management programs in the United States. Sport Management Review, 11, 77-91.

8. Kelley, D.R., Beitel, P.A., DeSensi, J.T., & Blanton, M.D. (1994). Undergraduate and graduates sport management curricular models: A perspective. Journal of Sport Management, 8, 93-101.

9. Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. (1999). Designing qualitative research. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks, CA.

10. NASSM (2015). North American Society for Sport Management. Sport Management Academic Programs. Retrieved from:https://www.nassm.com/Programs/AcademicPrograms

11. Schoepfer, K. L., & Dodds, M. (2011). Internships in sport management curriculum: Should legal implications of experiential learning result in the elimination of the sport management internship? Marquette Law Review, 21(1), 183-201.

12. Slack, T. (1991). Sport management: Some thoughts on future directions. Journal of Sport Management, 5, 95-99.

13. Tungjaroenchai, A. (2000). A comparative study of selected sport management programs at the master’s degree level. Retrieved from microform publications. no: 48059588.

14. Williams, J. (2003). Sport Management Internship Administration: Challenges and chances for collaboration. NACE Journal, Winter (2), 28 – 32.

15. Yiamouyiannis, A., Bower, G.A., Williams, J., Gentile, D., & Alderman, H. (2013). Sport management education: Accreditation, accountability, and direct learning outcome assessments. Sport Management Education Journal, (7)1, 51-59.