Authors: Bradley, Robert & Bruce, Scott L.

College of Nursing and Health Professions, Arkansas State University

Corresponding Author:

Robert Bradley, EdD, LAT, ATC

PO Box 910

Arkansas State University, AR. 72467

rbradley@astate.edu

870-972-3766

Robert Bradley is the program director of the master of athletic training program at Arkansas State University. He is an assistant professor in the College of Nursing and Health Professions and the curriculum coordinator for the Arkansas Athletic Trainers Association.

Scott L. Bruce is a research faculty member for the master of athletic training program at Arkansas State University. He is an assistant dean for research and an associate professor in the College of Nursing and Health Professions

Financial Budgets of Collegiate Athletic Training in South Carolina: A five-year review

ABSTRACT

Purpose: To compare financial patterns of collegiate athletic training budgets in South Carolina over a five-year span in order to determine if athletic training budgets meet or exceed changes in national economic trends and university athletic spending.

Methods: This longitudinal study of South Carolina colleges and universities to determine if gaps or excesses in the athletic training budgets demonstrate a trend that could be affecting the level of care. Additionally, to compare the change in resources and spending with inflation, college athletic department spending and medical spending per athlete and then provide the data on the patterns of collegiate athletic training financial resources to inform college athletic trainers on the trends over time. We mailed surveys to head athletic trainers or athletic directors at the thirty-two institutions that host intercollegiate athletics in South Carolina then compared the data to the 2014-2015 data already recorded.

Results: Ten schools returned surveys (N=10) for a 31% return rate. All athletic training budgets grew at a rate slightly higher rate (1.8%) than the annual inflation rate of 1.6%. Comparatively for the same five-year span, the average athletic department budget growth exceeded 7.8%. Spending for athletic training salaries increased by 20% to an average of $43,800. Total spending on or for athletic training costs rose from $307,438 in 2014 to $335,260 in 2018-2019. Combined with the total number of student-athletes to care for, athletic training spending average increased from $894 to $1119 spent per student-athlete in 2019.

Conclusion: Collegiate athletic training budgets are increasing over time slightly lower than the cost of inflation and much lower than the overall athletic department spending. Athletic training salaries are increasing over time. Athletic training budgets do outpace inflation but fails to match the overall growth of athletic department budgetary increases.

Application in Sport: Financial resources for athletic training at the collegiate level need to match the spending behaviors of the overall parent athletic department to provide adequate medical care to intercollegiate athletes. Failure to understand the patterns of change to an athletic training budget may place the ability of athletic trainers to care for student-athletes in jeopardy.

Key Words: budget, college athletic training, financial resources, salaries, spending

INTRODUCTION

The topic of athletic training budgets has not been a commonly researched topic in the field of athletic training. As such, there are few publications on the topic. Specifically, little data exists on the financial budgets used by athletic trainers to facilitate medical care for student-athletes. Historically, the athletic training budget includes items and expenses needed to run an athletic training room and the services it provided.

A budget is much more than numbers on a spreadsheet. One definition of a budget is “a plan for the coordination of resources and expenditures” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Wildavsky described a budget called the spending ceiling where all expenses that exceed the previous annual budgets must be accompanied by an explanation for the increased expenditure (Wildavsky, 1975)

In the collegiate setting most of the athletic training (AT) budget is appropriated to the athletics department (Allen-Burnstein, 2011; Bagnell, 2001; Desrochers, 2013; Fulks, 1993; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012; Manos, 2003; Nass, 1992; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; Rankin and Ingersoll, 2006; Vangsness et al., 1994). Colleges and universities allocate money to athletic training services to provide medical and health care to student-athletes (Prentice, 2021). Unlike other budgetary allotments in the athletics department, the AT budget serves the entire athletic participant group of the athletic population rather than a single sport.

The AT budget includes, but is not limited to the purchase of supplies and equipment. Some schools allocate for athletic trainers’ salaries and benefits as well (Bagnell, 2001, Bradley, 2010; Konin and Ray, 2019; Prentice, 2021; Rankin and Ingersoll, 2006; Wildavsky, 1975). Supplies include items with a single or limited use, such as athletic tape, band-aids, or gloves. Equipment for athletic training includes items such as tables or modalities that last longer but have larger initial costs. Capital expenditures can include equipment but are typically used for larger structural purchases and are not part of the athletic training budget or a focus of this study (Konin and Ray, 2019).

In 1992, Rankin explored athletic training spending in several categories including supplies and equipment (Rankin, 1992). His research, including every level of NCAA athletics and high schools, recorded the average AT department budget in 1992 was $232,546. The 1992 athletic training budgets amounted to $497 per student-athlete based on an average of 467 student athletes per school (Rankin, 1992).

In 2014 Rankin’s research, reporting of athletic training budgets and itemized items was replicated for 4-year schools with intercollegiate athletics in the State of South Carolina (Bradley et al., 2015). At the time, the average South Carolina athletic training budget was $381,245 and included purchases for supplies and equipment, maintenance, money to retain physician services, salaries, benefits, professional dues, malpractice insurance, office supplies and medical service spending. South Carolina 4-year schools averaged 320 student-athletes and allowed $1191 per student-athlete in athletic training expenses (Bradley et al., 2015). Specific items in the budget changed between 1992 and 2014. Specifically, the average expense for supplies remained steady but the capital equipment budget increased by 47%. Additionally, schools increased budgets for medical services (to include physical therapy) by 231%, medical insurance by 115%, and athletic training salaries by 12% Full-time athletic training staffing increased by 20%.

This change in AT budgets per student-athlete from $496 in 1992 to $1191 in 2014 represents a +140% change overall and +11.7% annually. This increase is substantiated by both the NCAA and Fulks reports that report a 161.5% and 7.34% annually respectively from a mean of $232,546 in 1992 to $381,245 in 2014. While indicating a growth that outpaces the inflation rate of 63.8% or 2.27% annually (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.), this data is lower than the overall total athletic budget changes of 296% or 15.6% annually between 1992 and 2014 (Fulks, 1993; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012).

Studies have shown that the available money within an athletic training budget does impact the medical care an athletic trainer can provide (Allen-Burnstein, 2011; Wham, 2006). Larger budgets allow ATs to purchase the proper supplies and equipment to prevent injuries and care for athletes. Wham found that schools with athletic training budgets greater than $3500 could provide athletic medical care closer to the recommended levels of Appropriate Medical Care for Secondary School-Age Athletics (AMCSSAA) than those with smaller budgets (Wham, 2006). In a study of athletic training budgets in the state of Nevada, research found that 89% of responders reported having budgets less than $3500 and 19% of those with less than $1000. She concluded that schools in Nevada should have at least $1000 set aside for athletic training and that schools with larger budgets could purchase levels of supplies that helped athletic training programs provide better care (Allen-Burnstein, 2011).

The purpose of this study was to determine the change in the size of the collegiate athletic training budget in a five-year period between the 2014-2015 and the 2018-2019 academic years for the 4-year schools in South Carolina that offer intercollegiate athletics.

METHODS

Procedures

After institutional review board approval, a survey was mailed to the head athletic trainers or athletic directors at the 32 four-year colleges and universities in South Carolina. Schools represented the athletic levels of National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I including Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) and Football Championship Subdivision (FCS), NCAA Division II, National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), and National Christian College Athletic Association (NCCAA).

The same South Carolina collegiate athletic training survey instrument used for the data collection in 2014 was utilized in 2019. The procedure for the survey mailing followed the Dillman method of distribution (Allen-Burnstein, 2011; Wham, 2006). Two weeks following the initial mailing, follow-up surveys were sent to non-responding subjects.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Washington) (Microsoft Corporation, 2019) spreadsheet. Calculations were made for average scores, percentages and standard deviations for the 2019 data. The 2019 data was compared to the previously reported 2014 data, including the analysis of percentage changes and actual dollar amounts.

RESULTS

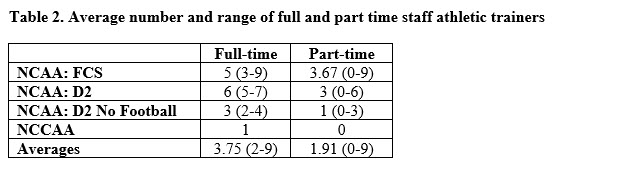

Ten schools responded (N=10) for a return rate of 31%. Responding schools represented four categories/levels of competition: FCS (n=3); NCAA Division II with football (n=3); NCAA Division II without football (n=3); and the NCCAA (n=1). These schools report an average athletic training budget of $335,260 (± $266,375) with 394 ± 98 athletes and 3.75 ± 1.4 full-time athletic trainers.

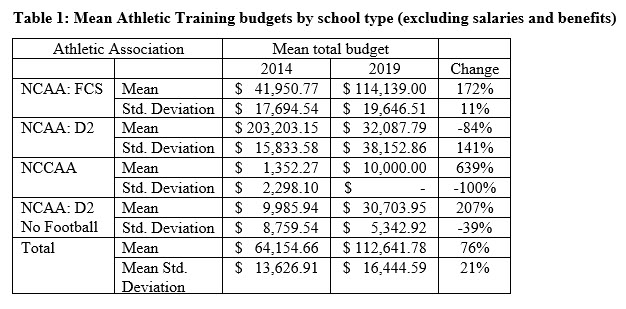

Between 2014-2019, athletic spending on everything minus salaries increased by an average of 76% (Table 1). Overall, athletic training budgets, to include salaries and benefits, increased at these ten institutions by 9% between 2014 and 2019. Analysis indicating trends in the reduction of professional dues and convention fees contrasted with increases in other areas of spending. The number of schools that provided malpractice insurance showed a small increase of 4% since 2014. However, the average amount of malpractice insurance rose by 86% from $536,603 to $1,000,000. As of 2019 only one reporting school’s malpractice insurance policy reached this million-dollar level. The NCCAA college did not break down their AT budget into categories but rather operated all athletic training funds in a single line-item budget.

No schools reported spending any money to retain the services of a physician in either 2014 or 2019. However, schools did report a 9% increase in the number of physicians under contract to provide services to their athletes. The data show that schools retained the services of just over four physicians per athletic level with a range of 5. The NCCAA school and NCAA D2 schools reported three physicians retained. As the number of physicians increased, so did the size of the athletic training staffing. Full-time athletic training staffs grew by 24% in 5 years; part-time staffing increased by +70%. (see Table 2)

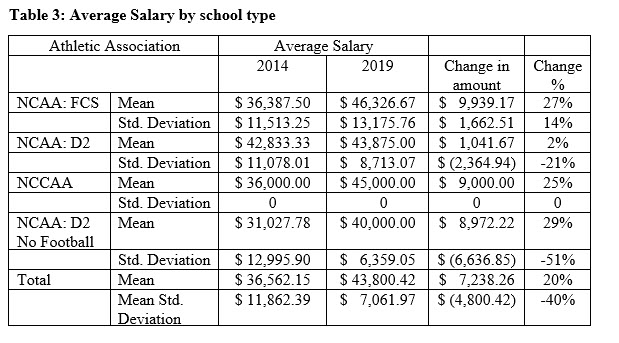

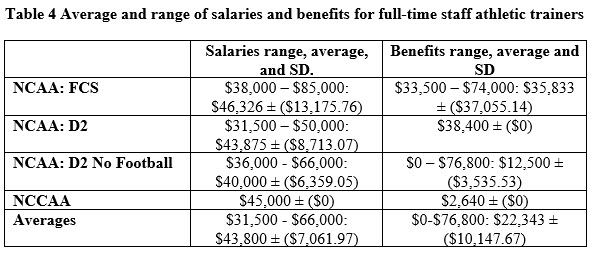

Compensation for athletic trainers also increased by 20% from an average salary of $36,562 to $43,800 between 2014 to 2019 across all athletic levels with benefits rising by 1027% from $1,983 to $20,360. Athletic trainer salaries increased by 27% at FCS schools, 2% at NCAA: D2 schools, 29% at NCAA: D2 no football, and 29% at the NCCAA school in the study (Table 3). While salaries increased slightly, benefits provided to full-time athletic trainers increased substantially. Benefits such as retirement and medical insurance increased by 2886% at FCS schools, 1820% at NCAA D2 schools, 168% at NCAA D2 schools with no football and 3420% at the NCCAA school. (see Table 4).

Even with the increases in pay and benefits, the South Carolina schools fall below the average in their district. The National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) divides the United States into 11 distinct districts. South Carolina is categorized as part of District 3. The reported average salary for District 3 in 2014 reported to be $52,878 while our data show that South Carolina averaged $36,562 in that same year (National Athletic Trainers’ Association Salary Survey, 2022). The 2018 NATA Salary Survey report showed that District 3 athletic training salaries averaged $55,426 and South Carolina full -time clinical college ATs earned $46,000. In 2021, the NATA Salary Survey report indicated that District 3’s new average for ATs rose to $59,985, yet full-time clinical college AT’s in South Carolina income decreased by 10.8% (-2.7% annually) to $41,020 (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.). The research herein reported clinical college ATs at participating institutions earned $43,800 in 2019. This number is 97.8% of the $44,755 that the 2019 NATA salary survey data suggest they should be making.

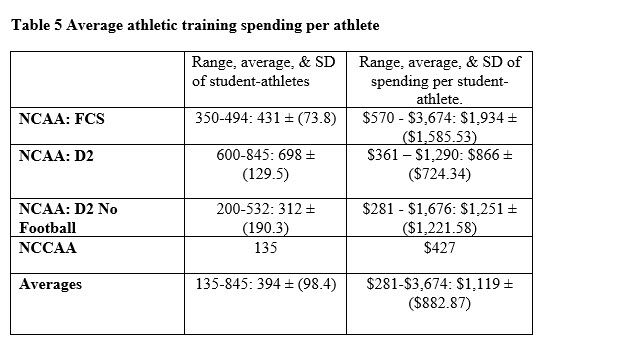

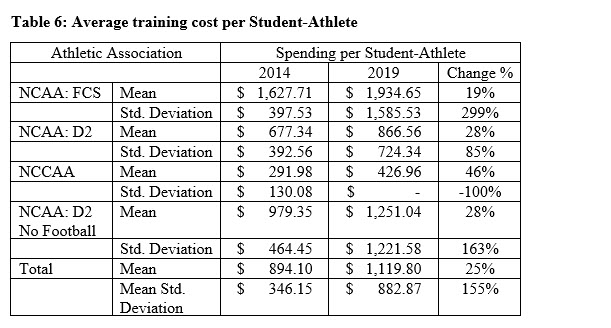

While salaries, benefits, and overall budgets grew, the total number of student-athletes at each participating institution also rose by 12%. Specifically, the percentage of student-athletes at the FCS schools increased by 18%, NCAA D2 schools with football increased by 2%, NCAA D2 schools without football increased by 12%; and the NCCAA institution had a 38% increase. Athletic training spending per student-athlete increased by 25% across all participants. NCAA D2 increased their spending the most by 46%, followed by NCCAA with a 38% increase, NCAA D2 without football by 25% and FCS schools by 19% (see Table 5). Average spending per student-athlete increased by 25% between 2014 to 2019 from a mean of $894 in 2014 to $1,119 in 2019 (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

This research compared financial patterns of collegiate athletic training budgets in South Carolina over five years to determine if athletic training budgets meet or exceed changes in national economic trends and university athletic spending. This paper reports the changes over a five-year span between 2014 to 2019. Total AT spending at these colleges increased 1.8% annually during from $307,438 in 2014 to $335,260 in 2019. This growth slightly exceeds the 1.6% annual consumer price index (CPI) (inflation) for the same period (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.) and falls just short of the growth of college tuition changes of 1.9% annually (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.). However, athletic department spending surpassed this growth at 7.4% annually across all NCAA schools (National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020).

The overall increase in athletic training budgets allowed for some notable changes in budget items, including +53% for expendable supplies, 288% for capital equipment, and +337% for maintenance. Athletic training department saw a 59% decrease in office supplies.

The largest percent increase in spending came from contracted expenses covering medical insurance and services like physical therapists or chiropractors. This budget category grew from an average of $1,689 in 2014 to $39,583 in 2019 (2243%). Data from both surveys show that not a single school reported spending any money to retain a physician, however, schools had an 11% growth for other medical services and insurance costs. The changes in contracted expenses from $1689 in 2014 to $39,583 in 2019 may indicate that subjects who completed the survey may not have clearly understood what was counted as medical insurance. This assumption is derived from the fact that later in the survey, participants were asked specifically about athletic medical insurance and responses indicated a 4% increase from 2014 to 2019.

The survey instructed subjects to report the numeric salary number for each fulltime AT. Participants were not asked to report position title, education level or work experiences of the ATs. The research herein assessed how institutions spent their money, without regard to distinguishing factors that separate athletic trainers from one another by virtue of titles or experience. Respondents listed salary figures in a simple list (ex. $41,000; $43,500; $57,000). Each dollar amount represented a full-time AT. Survey numbers show an average of 4% annual increase (20% total) in pay between 2014-2019. This information is slightly better but no significantly different than the -2.7% reported with the NATA salary survey (National Athletic Trainers’ Association Salary Survey, 2020).

Full-time AT benefits increased from $1,983 in 2014 to $22,343 in 2019 (1027%). These benefits included health, dental, vacation, hearing, retirement, and life insurance. The survey did not require the participants to break down their benefits by category or a dollar amount. Some responders stated that they did not know what their benefits were specifically, or they did not know the cost per benefit, just the total.

Budgets, for supplies over the five-year period increased by 52.9% or 10.5% annually. This increase exceeds CPI inflation numbers. Because this growth exceeds inflation and due to several items decreasing in price, the athletic trainer should have more purchasing power for supplies. Participants were not asked to explain changes to purchases behaviors resulting from the change in their budget amount or the price of supplies.

The growth of the AT budget compared to the larger total athletics department budget shows the same discrepancies reported in 2014. Between 1992-2014 the average AT budget grew at a rate of 11.7% annually, while the athletic department’s budget grew at a rate of 15.6% (Bradley et.al., 2015; Fulks, 1993; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012). Between 2014 to 2019, data from the study herein show AT budgets slowed in growth to 1.8% annually, while the NCAA reported that the average athletics department budgets increased by 15.02% annually. NCAA D2 institutions without football had the highest percent increase. This increase in budgets at NCAA D2 schools accompanied the largest athletic training salary increase and on the average increase in spending per student-athlete when compared to the other intercollegiate athletic levels (National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020).

For at least the past 30 years, colleges have grown their athletic department spending above 15% annually (Fulks, 1993; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012; Fulks, 2012; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020) while the budgets for AT have not increased by more than 12% and some have actually declined recently. The NCAA states that the average total athletic expenses of each Division 1 level exceed $80 million for FBS, $20 million for FCS and $18 million for D1 subdivision (National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020). The NCAA reported that DI schools spend 1-2% of their budget on general medical expenses. However, this report did not describe what is considered as a medical expense (National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020). If medical expense spending at 1% percentage is true, then FBS schools would be spending over $800,000, FCS over $200,000 and DI subsections over $180,000 annually on medical expenses. While the data from participants only show evidence of the DI schools in one state, responders reported less spending on AT than any of the medical expense numbers reported by the NCAA above. The NCAA does not require schools to spend a percentage of their expenses toward AT salaries and benefits. Findings from the current study indicate that the larger FBS schools have more full-time staff than smaller institutions.

One other source for reported athletic revenue and expenses is published by the Department of Education under the Equity in Athletics Discloser Act (EADA) (Department of Education, 2021). A 1993 law requires, “…institutions of higher education to disclose gender participation rates and program support expenditures in college athletics program to prospective students and, upon request to the public” (Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act, 1993). Annually, all colleges must submit a report to the Department of Education (DOE) outlining where they spend their money regarding the sports by gender and coaches’ salaries.

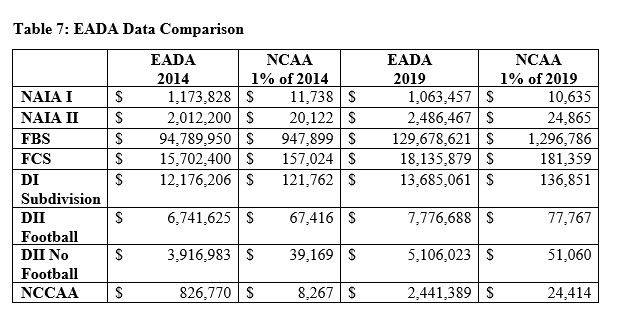

According to the EADA data from 2014, South Carolina 4-year schools averaged expenses of $12.9 million a year. Table 7 shows differences between levels of institutions based on the values reported from the EADA document (Department of Education, 2021) and the amount the NCAA reports schools should pay as part of their medical services spending (National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020; National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2020). If institutions followed EADA documentation on spending for medical spending, to include athletic training in 2014, institutions should have averaged $307,438; the data from the research on South Carolina schools spent only $171,675 (-44%). For 2019, EADA documentation, schools would spend an average of $335,260 on medical care, while data from the research on South Carolina schools averaged $225,467 (-33%).

How much money does an AT program need to function? There needs to be a minimum requirement for athletic training spending based on the number of student-athletes and sports for which the athletic trainer provides care. Each athletic training department must have a minimum amount of money in its budget to adequately provide care for its student-athletes. That amount should grow annually at the same rate that the average athletics department budget grows or at least grow at the same rate as inflation. The amount of spending should be based on the number of student-athletes cared for and not based upon previous budget spending.

LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The purpose of this study was to determine the change in the size of the collegiate athletic training budget at South Carolina institutions over a five-year period. Because research was limited to the state of South Carolina, the sample size of schools does not reflect the diversity of colleges nationwide. There may also be some hesitancy of subjects to share financial information or the ability to gain access to the requested financial information. Application of the survey needs to be extended to all 4-year schools nationally to gain a better reflection of athletic training budgets around the country. There needs to be regular assessment of the trends in athletic training financial resources including spending practices and supply and equipment cost trends.

CONCLUSION AND APPLICATIONS TO SPORT

The purpose of this paper to compare the financial patterns of collegiate athletic training budgets in South Carolina over time indicates that collegiate spending on AT services continues to increase but not at the pace of the overall athletic department spending. Evidence shows that spending on AT services represents a small percentage of the total overall athletic budget spending with NCAA schools. The data from South Carolina show that the rate of AT budget growth has slowed from 11.7% between 1992-2014 to 5% between 2014-2019. When analyzing spending per athlete, the AT budget has increased at the same pace as inflation. Athletic training salaries continue to rise, but data from this current research suggests South Carolina colleges pay lower than the NATA regional average.

REFERENCES

- Allen-Burnstein, B. (2011). An assessment of medical care provided by Nevada’s High School Athletic Programs (dissertation).

- Bagnell, D. (2001, January). Budget planning crucial in developing programs. NATA News, 15.

- Bradley, R. (2010). A Comparison of Athletic Training Program Financial Resources. The Sport Journal, 13(1), 2–6.

- Bradley, R., Cromartie, F., Briggs, J., Battenfield, F., & Boulet, J. (2015). Ratios of certified athletic trainers’ to athletic teams and number of athletes in South Carolina Collegiate Settings. The Sport Journal. https://doi.org/10.17682/sportjournal/2015.007

- Department of Education. (2021). Equity in Athletics Data Analysis. Equity in Athletics. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://ope.ed.gov/athletics/#/datafile/list

- Desrochers, D. (2013, January). Academic spending versus athletic spending: Who wins? Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED541214.pdf

- Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act, H.R.921. 103 Cong. (1993)

- Fulks, D, L. (1993). NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Intercollegiate Athletic Programs – Financial Trends and Relationships. Retrieved March 18, 2022 from: http://www.ncaapublications.com/p-4262-research-revenues-and-expenses-of-intercollegiate-athletics-programs-financial-trends-and-relationships-1993.aspx

- Fulks, D. L. (2012). Revenues and Expenses: 2004-2012 — NCAA Division I Intercollegiate Athletics Programs Report. Retrieved March 18, 2022 from: https://www.ncaapublications.com/p-4306-revenues-and-expenses-2004-2012-ncaa-division-i-intercollegiate-athletics-programs-report.aspx

- Fulks, D. L. (2012). Revenues and Expenses: 2004-2011 — NCAA Division II Intercollegiate Athletics Programs Report. Retrieved March 18, 2022 from: http://www.ncaapublications.com/p-4299-revenues-and-expenses-2004-2011-ncaa-division-ii-intercollegiate-athletics-programs-report.aspx

- Fulks, D. L. (2012). Revenues and Expenses: 2004-2012. NCAA Division III Intercollegiate Athletics Programs Report. Retrieved March 18, 2022 from: http://www.ncaapublications.com/p-4330-revenues-and-expenses-2004-2012-ncaa-division-iii-intercollegiate-athletics-programs-report.aspx

- Konin, J. G., & Ray, R. (2019). Management strategies in athletic training. Human Kinetics.

- Manos, K. T. (2003, December). Trimming the Athletic Budget. Coach & Athletic Director. Retrieved from: https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Trimming+the+athletic+budget.-a0111455093

- Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Budget definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved August 29, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/budget.

- Microsoft Corporation. (2019). Microsoft Excel. Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel

- Nass, S. J. (1992). A Survey of Athletic Medicine Outreach Programs in Wisconsin. Journal of Athletic Training, 27(2), 180–183.

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (n.d.). Digest of Education Statistics, 2020. National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Home Page, a part of the U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_330.10.asp

- National Collegiate Athletics Association. (2020). 2004-2019 NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Division I Intercollegiate Athletics Programs Report. NCAA Research. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/2020RES_D1-RevExp_Report.pdf

- National Collegiate Athletics Association. (2020). 2004-2019 NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Division III Intercollegiate Athletics Program Report. NCAA Research. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/2020RES_D3-RevExp_Report.pdf

- National Collegiate Athletics Association. (2020). 2004-2019 NCAA Revenues and Expenses of Division II Intercollegiate Athletics Programs Report. NCAA Research. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/Finances/2020RES_D2-RevExp_Report.pdf

- Prentice, W. (2021). Principles of Athletic Training: A Guide to Evidence-Based Clinical Practice (17th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Rankin, J. (1992). Financial resources for conducting athletic training programs in the collegiate and high school settings. Journal of Athletic Training, 27, 344–349.

- Rankin, J., & Ingersoll, C. (2006). Athletic Training Management: Concepts and Applications. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Salary survey. NATA. (2020, July 10). Retrieved March 10, 2022, from https://www.nata.org/career-education/career-center/salary-survey

- Salary survey. NATA. (2022, July 15). Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://www.nata.org/career-education/career-center/salary-survey

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Consumer Price Index 2014-2019. Consumer Price Index (CPI) Databases. Retrieved August 30, 2022, from https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm

- Vangsness, C. T., Hunt, T., Uram, M., & Kerlan, R. K. (1994). Survey of health care coverage of high school football in Southern California. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 22(5), 719–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354659402200524

- Wham, G. S. (2006). An examination of medical care for high school athletics in South Carolina (dissertation).

- Wildavsky, A. B. (1975). A comparative theory of budgetary processes. Little, Brown and Co.