Submitted by Robert Bradley1, Ed.D, ATC, SCAT*. Fred Cromartie2, Ed.D*, Jeff Briggs3 PhD.*, Fred Battenfield4, Ph.D.*, Jon Boulet5 Ph.D*.

1* Assistant Professor of Sport management at North Greenville University, Tigersville, South Carolina, 29680

2* Director of Doctoral Studies at the United States Sports Academy, Daphne, Alabama, 36526

3* Professor of Sport Management at North Greenville University, Tigersville, South Carolina, 29680

4* Professor of Sport Management at North Greenville University, Tigersville, South Carolina, 29680

5* Professor of Economics at North Greenville University, Tigersville, South Carolina, 29680

Robert Bradley is a certified athletic trainer and assistant professor at North Greenville University. He is an expert in the financial resources of athletic training and appropriate medical coverage research.

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

The National Athletic Trainers’ Association produced a recommendation for the appropriate medical coverage of college athletics back in 1998.1 The purpose was to determine how many certified athletic trainers (ATC’s) they need to have to reach the NATA’s minimum recommendation. Despite the recommendation, there has been no review of the application of this recommendation in colleges since its inception. This research was to determine the current ratios of full time athletic trainers to the number of athletic teams and student-athletes in the collegiate setting in South Carolina.

Method:

Cross-sectional study, using an open ended questionnaire sent to the head athletic trainers or athletic directors of the 32, four year colleges in South Carolina that support intercollegiate athletic teams. The subjects represented FBS, FCS, NCAA DI no football, NCAA DII with football, NCAA DII without football, NAIA, and NCCAA schools. Results were compared to the original results from Rankin’s survey.

Results:

Of the 32 available schools 23 responded for a 72% return rate. The number of full time athletic trainers in South Carolina colleges and universities rose from 3.0 in 1992 to 3.6 in 2014. The ratio of student-athletes to full time athletic trainers decreased from 115/1 to 87/1. The ratio of sports to full time athletic trainers fell from 6/1 to 4/1 in the same time period. Public schools report more full time athletic trainers with fewer sports than their private college counterparts.

Conclusion:

Colleges in South Carolina are attempting to address the NATA’s Appropriate Medical Coverage statement. The ratio of student/athletes and teams to full time athletic trainers shows an effort by schools to address the medical coverage needs of their college student athletes. Public colleges report having fewer sports and more full time athletic trainers than private colleges.

Application in sports:

In order for colleges in South Carolina and other states to meet the standards for appropriate medical coverage as determined by the National Athletic Trainers Association, colleges will need to hire additional full time athletic trainers.

Key Words: Ratio, Medical Coverage, Public Colleges, Private Colleges

INTRODUCTION

In 1992, James Rankin published a report on the strength of the financial resources for college and high school athletic training programs (9). The topic of athletic training budget concerns has fallen generally to the healthcare administration competencies presented by the National Athletic Training Association (NATA) for the Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE), who accredits athletic training education programs (9)

The idea of having an athletic trainer is still considered a luxury in many high schools with restrictive budgets (12). According to the NATA only 42% of high schools have athletic trainers (13). Most colleges and universities have at least one full time athletic trainer.

The NATA’s attempt at addressing the topic of appropriate medical coverage started in 1998 when the organization came out with its original documentation. Since then the original document has undergone changes. The current incarnation of the appropriate medical coverage recommendation and the NATA website specifically state that, “institutions are encouraged to view these recommendations as guidelines, not mandates, taking into consideration their unique individual needs. We encourage institutions to consider these recommendations a “living document” because further revisions may be required as more information becomes available, or as preventative techniques, rules and policies change” (8).

This statement provides each college the autonomy to determine how many full time athletic trainers they will need to provide such the appropriate care. To date, no publications have any record of the number of full time or part time athletic trainers at the college setting and the ratio of athletes and sports to those athletic trainers who provide care.

METHODS

The purpose of this study was to replicate part of Rankin’s 1992 research by requesting college head ATC’s to report the size of their budget, as well as, provide information to its athletic association (NCAA, NAIA, NCCAA) division level, number of total athletes, and what style of budget their department uses.

The selection of subjects was limited to colleges and university institutions in the state of South Carolina offering four year degrees and collegiate athletics (including NCAA, NCCAA, and NAIA members). From that population, a sampling of colleges and universities within the state of South Carolina were selected. This researcher has determined there were 32 qualified institutions in South Carolina that offer intercollegiate athletic programs. There were two FBS schools, 10 FCS schools, 13 Division II, five NAIA, and two NCCAA schools that represent the subject pool.

The representatives at these colleges and universities were the head athletic trainers, or their equivalent, at each school. The names, e-mail addresses, work addresses, and work telephone numbers of the subject schools were taken from each schools respective athletic websites. All information was kept in confidence.

INSTRUMENTATION

An open ended survey was sent to the head athletic trainers using the modified Dillman method. Subjects were asked questions regarding funding affiliation (public or private), number of sports, number of athletes, and number of full and part time athletic trainers.

The Modified Dillman method was implemented due to its use in prior athletic training related surveys (2-4, 6, 10-11, 14). The Modified Dillman method has been shown to increase return rates when applied (1, 5).

An envelope containing a cover letter, survey, and a Self-Addressed Stamped Envelope (SASE) was sent to the subjects. Subjects were asked to complete the survey and use the SASE to return the survey back. As the responses came in that responder was removed from the non-responder list. All data was held by this researcher in confidence. Completion of and return of the survey was understood as a willingness to participate in the study.

RESULTS

Using the modified Dillman method, paper copies of the surveys were mailed to the subjects. Twenty-three of the 32 schools responded for a return rate of 72% (n = 23). Both the FBS schools replied as well as 8 of 9 FSC, the only D1: no football, 3 of 4 D2, 6 of 9 D2: no football, 1 of 5 NAIA, and both NCCAA schools.

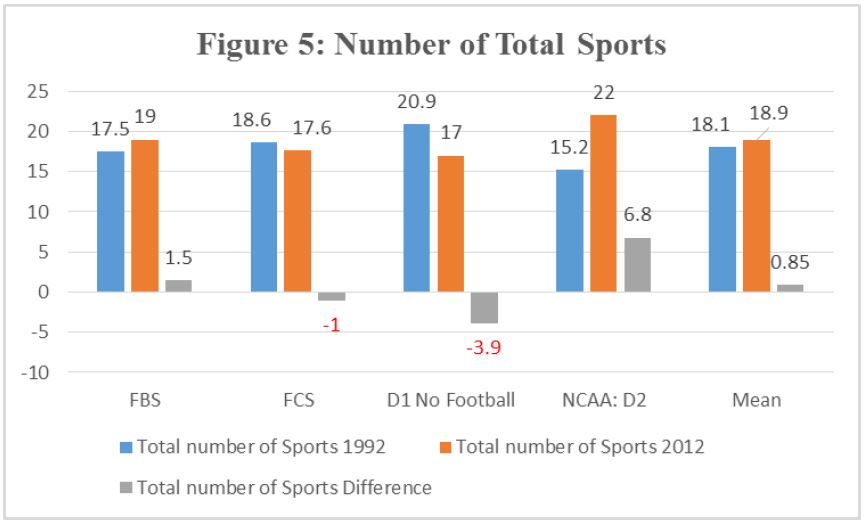

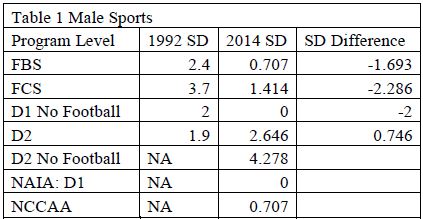

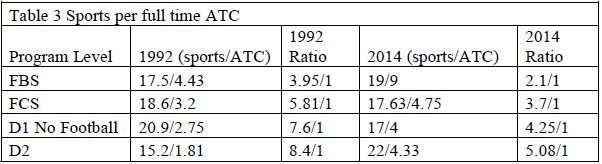

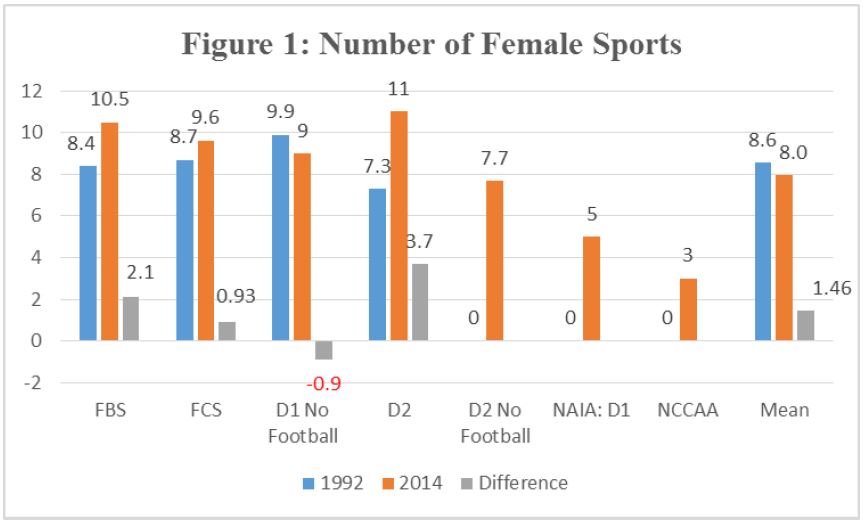

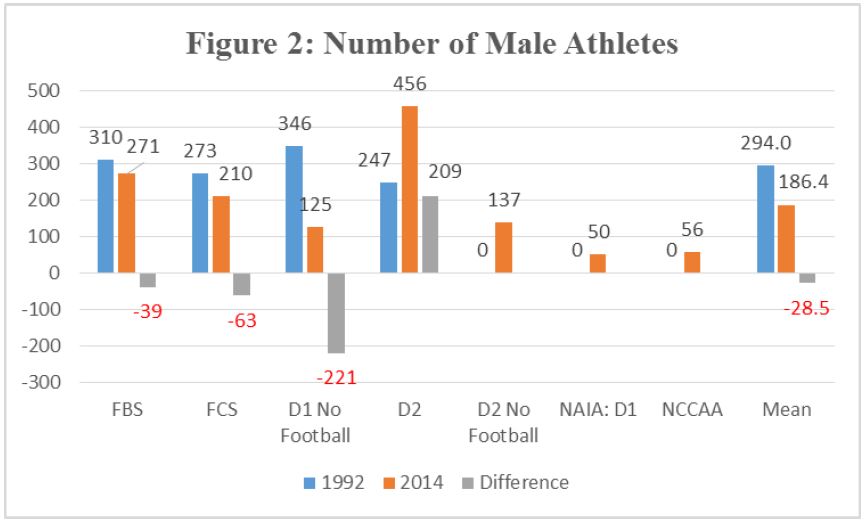

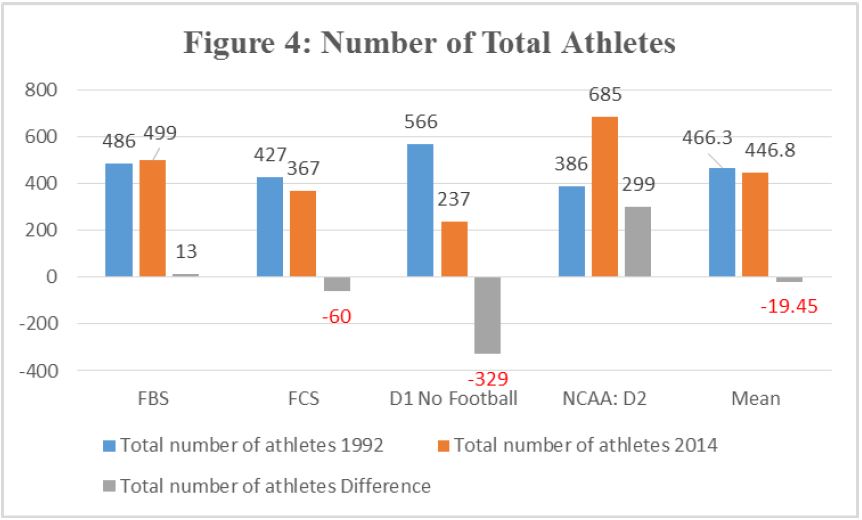

According to the findings of this study when comparing the numbers to the original 1992 Rankin report, the average number of males sports decreased by 4%. FBS schools decreased by 7%, FCS by 19%, DI: no football decreased by 27%, and D2 with football increased by 39% (Table 1).The number of female sports increased by an average of 20% between the years of 1992 and 2014. FBS saw a 25% increase, FCS an 11% increase, DI: no football had a 9% decline, and D II had a 51% increase. (Figure 1) The number of male athletes’ fell an average of 5% or a decrease of 28.5 athletes per school. FBS dropped by 13%, FCS fell by 27%, DI: no football dropped by 63%, and D II increased by 85% (see Figure 2). Female athletes increased in number at all but one category of school by 11.7%. FBS increased by 29%, FCS by 1.8%, D1: no football decreased by 49%, and D2 grew by 65%. (See Figure 3) The total number of athletes rose by 2% from 1992. FBS grew by 2.5%, FCS decreased by 14%, D1: no football saw the biggest change with a 58% decrease while the largest growth was with D2 at 77%. (See Figure 4)

Overall the total number of sports fell by an average of 15%. FBS grew by 8%, FCS shrank by 5%, D1: no football fell by 19%, and D2 decreased by 45%. (See Figure 5)

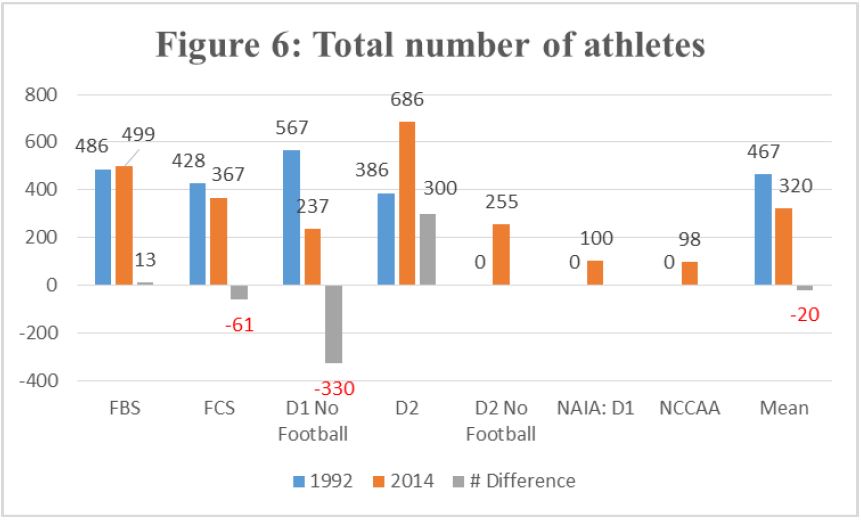

Total Number of Athletes

Since 1992 the number of sports teams has risen slightly as well as the total number of athletes for the four levels by an average of 2%. FBS schools grew by 3%, FCS decreased by 14%, D I: no football decreased by 58% and D II increased the most by 78%. (See Figure 6)

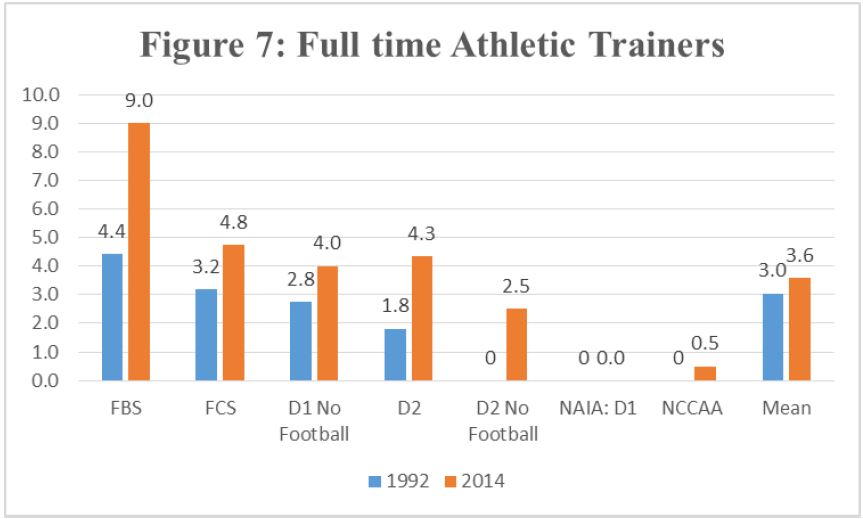

Full Time Athletic Trainers

The number of full time certified athletic trainers in 1992 was 3.05 for the four categorical schools. By 2014 it rose to 3.6 for all seven categories. According to the data from the four categories with both sets of data the number of full time certified athletic trainers increased by 184%. FBS increased their full time AT staff by 203%, FCS by 148%, D1: no football by 145% and D II increased theirs by 239%. The lone NAIA school reporting indicated that they had one athletic trainer from a local physical therapy clinic and did not claim him as a full time athletic trainer. (See Figure 7)

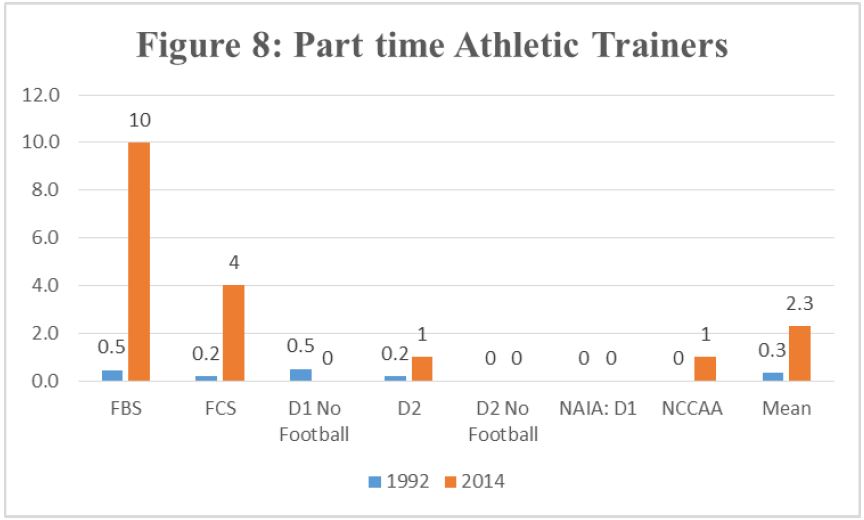

Part Time Athletic Trainers

The number of part time athletic trainers in collegiate settings grew by an average of 1182% for the four categories. FBS increased their by 2222%, FCS by 2000%, D1: no football decreased theirs by .5% and D2 increased theirs by 555%. (See Figure 8) No distinction was made as to whether these part time positions were graduate students working as graduate assistants or as non-student affiliated positions.

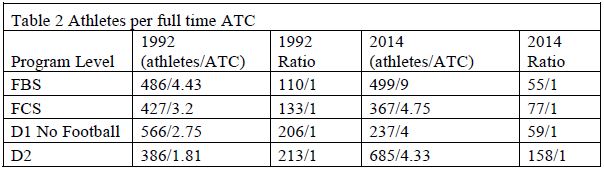

Ratio: Athletes per athletic trainer

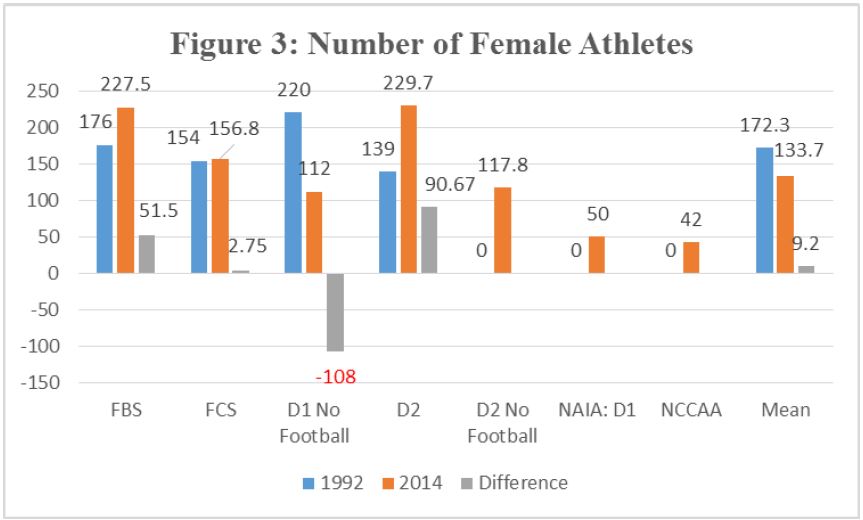

Rankin collected data on the number of sports teams by gender and category as well as the number of full time athletic trainers per school. What he didn’t do was determine the ratio between those variables. Table 3 shows the ratio data for the numbers of total athletes per full time athletic trainer. In every category the ratio of athletes to athletic trainer has decreased from a ratio of 155/1 to 87/1. (See Table 2)

Ratio: Sports per athletic trainer

This data shows that the ratio of the number of sports to athletic trainer decreased from 6/1 to 4/1. (See Table 3)

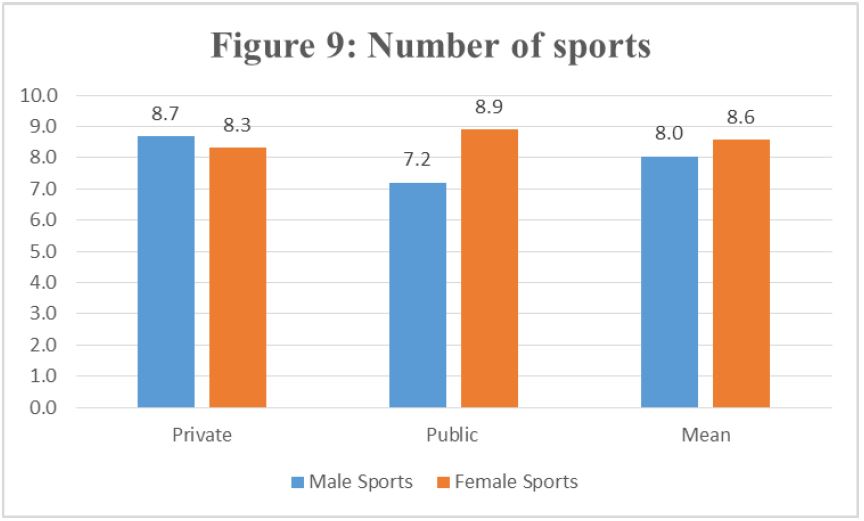

Number of sports: Public and Private

The same variables of: number of athletes, number of teams, benefits, salaries, spending and percentages was compared to school type either private or public. There were a total of 13 private and 10 public schools reporting. (See Figure 9)

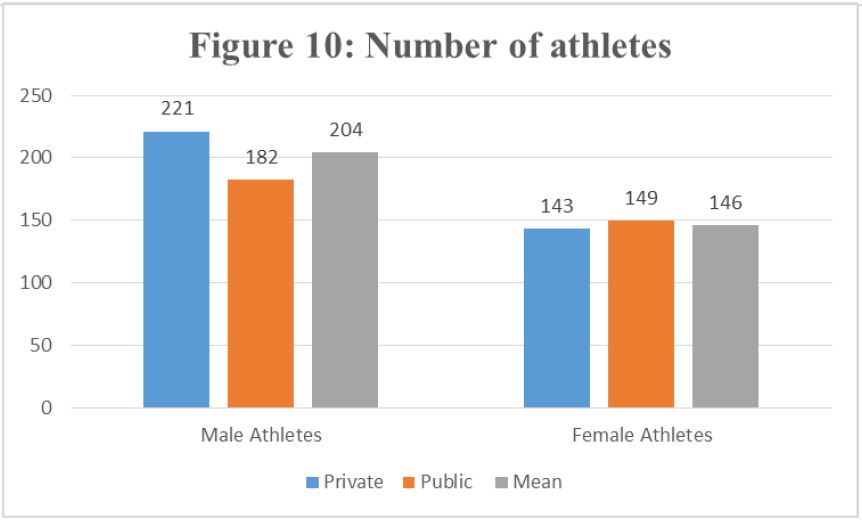

Number of athletes: Public and Private

The number of athletes per school type were compared. On average private schools had both more sports and a more athletes than public schools. (See Figure 10)

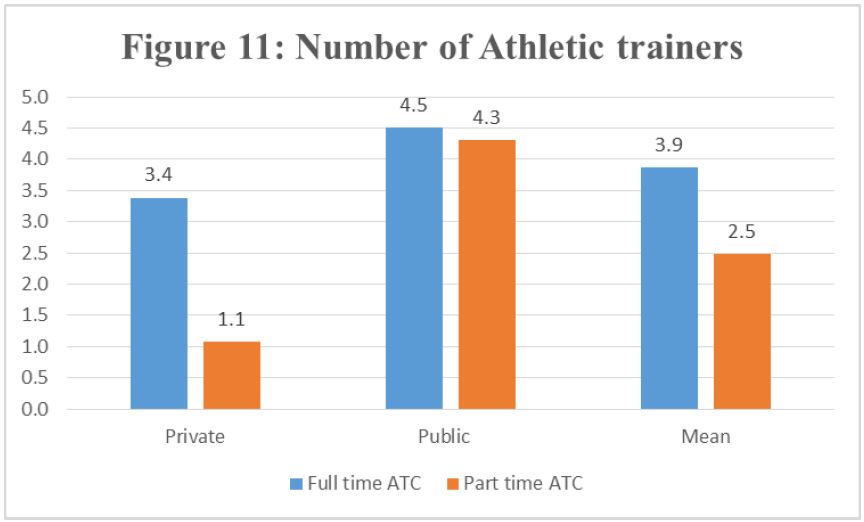

Number of athletic trainers: Public and Private

Looking at school type and the number of athletic trainers’ public schools had more full time and part time employees than private schools. (See Figure 11)

DISCUSSION

The lone NAIA, both NCCAA, and several NCAA Division 2 schools indicated that the athletic trainers that worked with their athletic departments were not employees of the school but rather outreach athletic trainers from hospitals or clinics. This may explain why the numbers were so small from some of the subjects. If a school can defer the cost of an athletic trainers salary to a third party and even ask that third party to pay for the typical supplies and equipment then each college would save a great deal of money. However, if a school were to defer said responsibilities to a third party that hospital or clinic may not be willing or able to contribute the financial resources and people necessary to provide the adequate standard of care the profession requires.

The purpose of this research was to compare the data from Rankins’ 1992 report to evaluate what changes have occurred between the years of 1992 and 2014. The first set of data gathered included data pertaining to schools athletic affiliation, school status (public or private), then asked how many male and female sports and athletes they had.

The first set of data collected dealt with the demographics of the parent athletic departments to which the athletic training department supplies services. During the years between 1992 and 2014 the number of male sports and male athletes decreased while the number of female sports and athletes increased. While no further questions asked to explain this change speculation was that the factors that could explain this change include: changes in sport interest, cost, or possibly complying with Title IX law. Overall schools were dropping sports, specifically male sports.

One set of data that came from this research pertaining to the decline of the number of sports was the increase in the number of full time athletic trainers. This ratio of one athletic trainer to six sports down to one for every four, as well as the decrease ratio from 155 for every one athletic down to 87/1, was an indication that schools were making an attempt to meet the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) standards for appropriate medical coverage.

One position to increase the number of athletes and sports was in both full and part time athletic training staff. All schools reported an increase in the number of full and part time staff. This includes the addition of staff at NAIA and NCCAA schools. Both of these schools indicated that the staff did not actually work for the school but as an outreach from a local hospital.

The growth of athletic training staff show that schools were making an attempt to reach the recommendations of the NATA with its 2010 appropriate medical coverage report. Although, even with the NATA recommendation each school has the autonomy to calculate their own athletic training staffing needs.

Public vs. Private Colleges

It was possible that in South Carolina that private schools have more sports for the specific purpose of creating revenue for the school because they are more dependent upon tuition dollars to remain financially afloat than public schools are.

Consider that in South Carolina private schools average 292 athletes each paying in some small way to attend that school. Compared to public schools that has on average only 256 athletes who pay in some small way part to attend the school. Because private schools do not have the depth of financial resources as public schools one can understand why tuition driven private schools have larger athletic departments than public schools.

Because staying financially afloat is important to private schools is also why private schools hire fewer full and part time athletic trainers (3.4 for private schools compared to 4.5 for public schools), and why private schools spend less with every category of spending including spending per athlete.

CONCLUSIONS

The first section results show a change in the demographics of the number of sports and the number of athletes. From 1992 to the current study, the number of male sports and male athletes has decreased while the number of female sports and athletes has increased.

The second section on athletic training staff demographics show that the number of full time and part time athletic trainers has increased.

In relation, the ratio of the number of sports and athletes to full time athletic trainers has decreased. But the number of full time athletic trainers still falls short of the NATA recommendations for appropriate care. Additionally, private schools have a higher number of sports and athletes to full time athletic trainers than public schools.

APPLICATION IN SPORTS

The profession of athletic training and the National Athletic Training Association are aware of the standards established by the NATA on appropriate medical coverage. Schools failing to meet theses safety standards are putting the schools at risk of legal and social image damage, the athletic trainers from malpractice law suits, and most importantly the health of the student-athlete.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None

REFERENCES

- Allen-Burnstein, B. (2011). An assessment of medical care provided by Nevada’s high

school athletics program (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nevada, Las Vegas). Retrieved from: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations/1253/ - 2. Biddington, C. M., Wagner, R. W., Lyles, A., & Brunner, M. (2009). Athletic Health

Care in Pennsylvania High Schools. Pennsylvania Journal of Health, Physical

Education, Recreation, and Dance (Winter), 20-24. - Buxton, B. P., Okasaki, E. M., Ho, K. W., & McCarthy, M. R. (1995). Legislative

funding of athletic training positions in public secondary schools. Journal of

Athletic Training, 30(2), 115-120. - Conaster, P., Naugel, K., Tillman, M., & Stopka, C. (2009). Athletic Trainers’ Beliefs

Towards Working With Special Olympics. Journal of Athletic Training, 44(3), 279-285. - Hoddinott, S. N. & Bass, M. J. (1986). The Dillman Total Design Survey Method: A

sure-fire way to get high survey return rates. Canadian Family Physician, 32,

2366-2368. - Janhunen, M. E. & Green, R. C. (1997). Injury management in high school athletics.

Coach & Athletic Director, 4-7. - National Athletic Trainers’ Association. (2011). Athletic Training Education

Competences. (5th ed.). Retrieved from: http://caate.occutrain.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/5th-Edition-Competencies.pdf - National Athletic Trainers’ Association. (2014). NATA Recommendations and

Guidelines for Appropriate Medical Coverage of Intercollegiate Athletics. Retrieved from: http://www.nata.org/appropriate-medical-coverage-intercollegiate-athletics - Rankin, J. M. (1992). Financial resources for conducting athletic training programs in

the collegiate and high school settings. Journal of Athletic Training, 27, 344-349.

Shaw, M. J., Beebe, T. J., Jenson, H. C., & Adlis, S. A. (2001). The Use of Monetary - Shaw, M. J., Beebe, T. J., Jenson, H. C., & Adlis, S. A. (2001). The Use of Monetary

Incentives in a Community Survey: Impact on Response Rates, Data Quality, and Cost. Health Services Research, 35(6), 1339-1346. - Tonino, P. M. & Bollier, M. J. (2004). Medical supervision of high school football in

Chicago: Does inadequate staffing compromise healthcare? Physician in Sports Medicine, 32(2), 37-40. - Vangsness, T. C., Hunt, T., Uram, M., & Kerlan, R. K. (1994). Survey of health care

coverage of high school football in Southern California. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 22, 719-722. - Waxenberg, R., & Satlof, E. (2009, March 12). Athletic Trainers Fill a Necessary

Niche in Secondary Schools. Retrieved from: www.nata.org/NR031209. - Wham, G. S., Saunders, R., & Sullivan, C., (2010). Key Factors for Providing

Appropriate Medical Care in Secondary School Athletics: Athletic Training Services and Budget. Journal of Athletic Training, 45(1), 75-86.