Submitted by Joan Sloan, Ph.D.

Dr. Jo Sloan is an Assistant Professor at Lane College teaching in the areas of Health, Physical Education and Recreation, and is also a certified Personal Trainer through the American Council on Exercise.

ABSTRACT

Surveys were sent to 231 randomly selected athletic administrators from the 2008-09 NCAA Directory of Colleges and Universities across the United States in Divisions I, II, and III seeking their perception of qualifications necessary for Black females seeking opportunities to head coach Women’s basketball programs at the Division I, II, or III level. The rate of return for the surveys was 67%. The statistical significance of the information was tested using t-tests, one-way ANOVAs, and the Tukey’s Post Hoc procedures. There were items of significance from the Athletic Directors across the divisions as it related to education (p<.00), qualifications (p<.00), being unaware of openings (p<.02), experience at their level (p<.00) and being single (p<.02). There was a significant result from the Commissioners as it related to experience (p<.02) for the division at its level. With the passage of Title IX some 42 years ago, the adoption of affirmative action guidelines and the increase in the number of women in sports one would be lead to believe that things would change especially for the Black female. However the number of minority women head coaches have not increased (Abney & Richey, 1992). Given as the top five perceived qualifications necessary for the employment of Black females according to athletic administrators were: strong communication skills, ability to recruit/travel, personality, educational level, and Division 1 coaching experience. Each division believed that experience at their level was definitely necessary. Having four out of the five qualifications and the Black female is still denied the opportunity. Between the years of 2000 and 2002, 90.3% of those new positions were filled by men (Acosta & Carpenter, 2002).

INTRODUCTION

There has been a decline in the number and percentage of female coaches. In 1972 the percentage of female coaches was 90% and in the 1990s that percentage dropped to 47 % (Abney, & Richey, 1991) (2). (Holmen & Parkhouse, 1981) discovered that the number of intercollegiate coaching positions for female teams increased by 37% between 1974 and 1979. Thus at the interscholastic and intercollegiate levels, the number of female athletic teams and available coaching positions for these teams dramatically increased thereby making it possible for the number of female coaches to remain relatively unchanged while the percentage of female coaches dropped, this was attributed to men filling the majority of those new coaching positions. In 2012, the percentage of Female coaches of women’s teams was 42.9 % (Acosta and Carpenter, 2012). The percentages of male coaches of women’s teams in 2012 were 57.1, so that percentage was above the percentage for female coaches coaching women’s teams (7). (LaVoi, 2013) researched the historical decline of women coaches since the passage of Title IX in 1972 in Division I, in an attempt to examine the employment patterns, and determine what can be done to retain females in coaching. (Brown, 2010) indicated that results from 2010 study shows the percentage of minority head coaches of women’s teams have increased 2.9 since 1995 – 96. Across all three divisions in 2008 – 2009, there were 59 Black Female head coaches of women’s basketball teams excluding the HBCUs. (Irick, 2011) calculated from the Race/Demographics Report across a span of 15 yrs. the number of Black female coaches at each level (No HBCU’s).

| 1995-96 | # B.F.C. | No HBCU’s | 2009-10 | # B.F.C. | No HBCU’s |

| Div. I | 27 | 18 | Div. I | 98 | 65 |

| Div. II | 20 | 9 | Div. II | 35 | 18 |

| Div. III | 19 | 16 | Div. III | 14 | 13 |

There are numerous views and misconceptions that relate to the qualifications that are perceived necessary for Black females pursuing open positions. (Acosta and Carpenter, 1985b) presented data at the intercollegiate level which reflects what might be the beginning of a new decline in the number and percentage of female intercollegiate head coaches. They attributed this to the new decision of 1984 which stated that “only departments and not entire schools receiving federal funds must provide equal opportunities for females in athletic departments.” The case of Grove City v Bell, 465 U. S. 555 (1984), dealt with the scope and applicability of Title IX. Given that most physical education and/or athletic departments do not receive federal funding, the Grove City decision suggested that such departments need not provide equal opportunities for female athletics. Findings by (McGrath, 1992) indicated that the primary reason for not considering Black women for leadership positions has often been their lack of qualifications. Black women are not mentored, so it is difficult to acquire the needed experience. They are screened out of the activities that encourage growth and teach competitive teamwork. They are underestimated and regulated to less important work; because it is perceived that they cannot handle the demanding responsibilities. Black women are patronized and they are not taken seriously by the existing leadership. With the lack of qualified female coaches, the opportunities to work with other females in those areas are scarce. In order for females to gain employment they must have higher qualifications than their male counterparts. Female applicants must provide evidence of their experience and proven success although male applicants are not asked to prove themselves in this way (Delano, 1990). Many Black women are not given the chance to prove what they can do in a demanding situation. (Houzer, 1974) explained that minorities of many strata have been particularly vociferous concerning a wide variety of social situations relating to Black women in athletics. The broad expansion of participation in sports and athletics by women has not been proportionally represented by Black women; this representation of Black women in sports and athletics is evident at all levels; interscholastic competition, coaching, officiating, and administration. Females are expected to fill both teaching and coaching roles, unless they are qualified for an academic area many times they are not considered for a coaching position (Acosta and Carpenter, 1992). There are times when job openings are posted only to satisfy regulation requirements because many of the administrators already have a replacement in line. Single women are often not considered for leadership positions because they are perceived to be lesbians. The single coaches feel that the opportunities to build relationships are limited because of stereotyped view points. Being the only Black female at a college or university creates more pressure and stress by creating isolation and exclusion from policy making formations which are very important in the world of sports (Thorngren, 1990). The public devaluation of the females’ contribution to sports is another factor that has predisposed the female to not being selected for leadership positions in the sporting arena. (Green, 1987) felt the process of trying to divide time between work and home caused anxiety and feelings of guilt for many women, which lead them to forego opportunities for advancement. The NCAA 2008 -2009 study from Gender Equity in Coaching and Administration indicated that the most important factor female coaches in all three divisions attributed to accepting a collegiate coaching position was the administration’s support of the women’s athletic programs and not the lack of qualifications (9).

METHODS

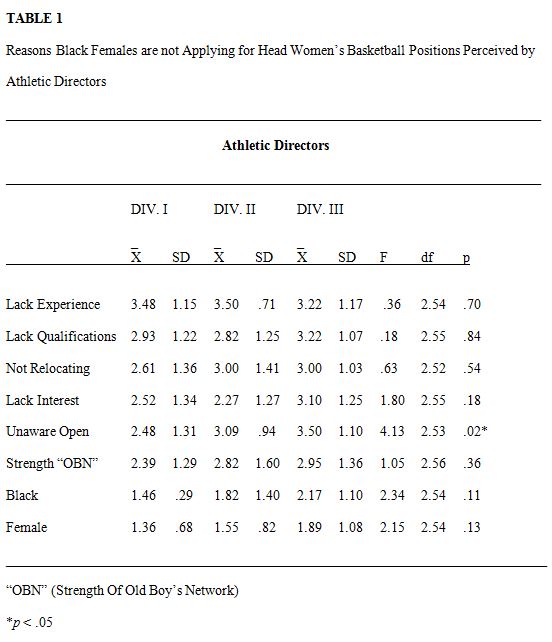

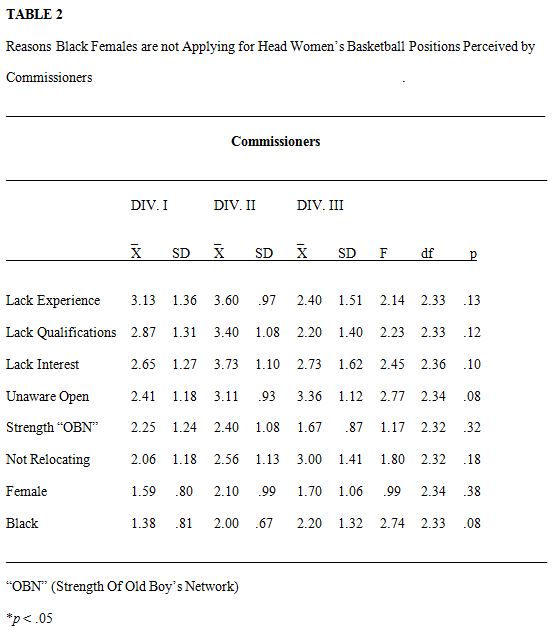

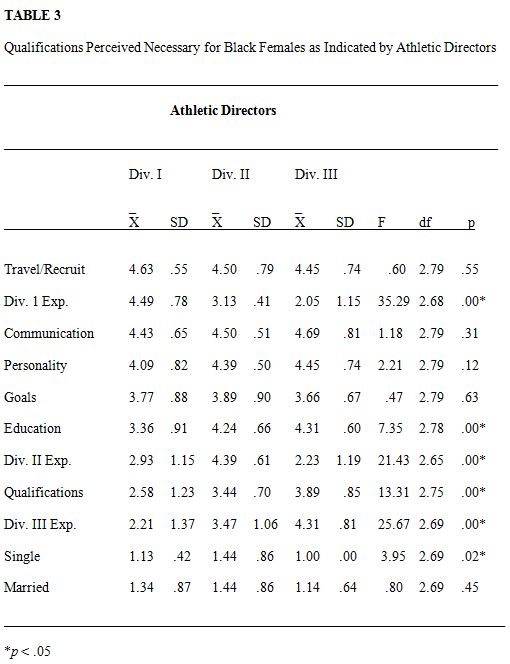

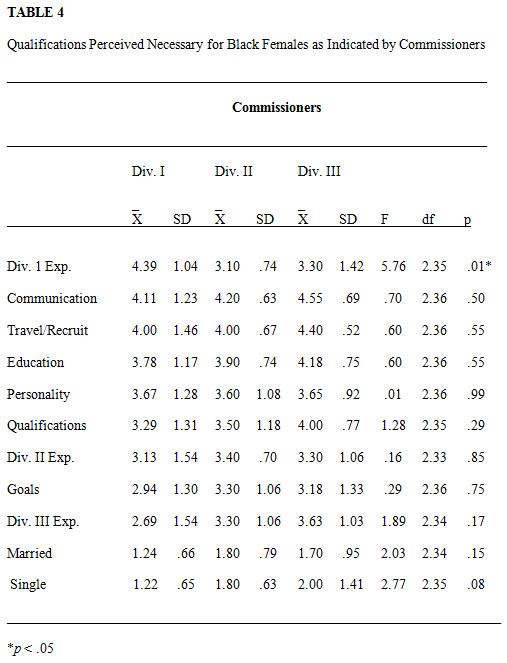

The research was pursued in an attempt to determine the qualifications necessary for Black females pursuing collegiate head women’s coaching positions in Division I, II, and III as perceived by athletic administrators, and to determine the reason (s) why Black females were not applying for open positions. A Human Subject Review Form/Consent Form was included with the survey to all participants. A revised questionnaire based on previous work by Abney, R. and Richey, D (1) was mailed to selected athletic administrators across Division I, II, and III. The questionnaires mailed to participants signified by the completion and return of the questionnaire their consent to participate in the research. The questions were rated on a Likert scale of 1 – 5, with 1 being considered low and 5 considered high. The questionnaire consisted of 2 sets of questions, one set with 8 factors (Tables 1 and 2) and the other set contained 11 factors (Tables 3 and 4) to rate on a scale of 1 – 5 with the opportunity to add an additional factor if desired on the initial questionnaire. The questions related to the level of experience of the administrators, the methods used for advertising, the number of Black candidates they interviewed while in that position, the reasons they perceive as to why Black Females are not applying for open positions and the qualification perceived necessary when applying for collegiate coaching positions.

One hundred and fifty-four athletic directors listed in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Bulletin were selected from across the United States representing Divisions I, II, and III. The selection process was based on 10% of the total number of athletic directors listed for each division. Eighty-eight athletic directors were selected from Division I. Twenty-seven were selected from Division II, and thirty-nine were selected from Division III.

Seventy-seven commissioners were selected from the National Collegiate Athletic Association Bulletin, representing basketball conferences across the United States from Divisions I, II, and III. Thirty-six were selected from Division I, fifteen were selected from Division II, and twenty-six were selected from Division III as part of the applicant pool for which the questionnaires were mailed for completion.

Each administrator received a cover letter along with the questionnaire and a self-addressed stamped envelope explaining the process and requesting their cooperation for the prompt return of the questionnaire. The questionnaires were received over a twelve week period, with a reminder after the first three weeks stating that the questionnaire had not been received and encouraging the completion of the second questionnaire. The questionnaires that were received after the end of the twelfth week were not included in the research.

The data was collected and coded according to the division. The statistical analyses of the data were completed using one-way ANOVA, t-tests, and Tukey’s Post Hoc procedures. The one-way ANOVA was used to determine the differences among Divisions I, II, and III athletic directors and commissioners. The t-test was used to determine the differences for the athletic directors and for the commissioners across each division. The Tukey’s Post Hoc procedures were used to determine where differences existed. The level of significance was set at p<.05.

RESULTS

The return rate for the questionnaires was 68% for the athletic directors and 66% for the commissioners. Based on the perceptions of athletic administrators, the reason (s) Black females were not applying for head women’s collegiate basketball vacancies; include the lack of experience, the lack of qualifications, the lack of interest, being unaware of job openings, and the unwillingness to relocate.

For the athletic directors (Table 1) across the divisions there was a significant difference (p<.02) in being unaware of job openings across the divisions. Division III indicated being unaware of openings as a 3.50, while Division II indicated a 3.09, and Division I indicated a 2.48. Division III indicated this factor to be more of a reason than Division I or II. Across the divisions it was felt that lack of experience was a major factor for Black Females not applying for job openings. For the commissioners (Table 2) being unaware of job openings (p<.08) and being Black (p<.08) were major factor that had some influence on the reasons for not applying for job openings but they were not significant. Lack of interest (p< .10) also had some influence in the decision but it was not significant. Table 3 indicated qualifications perceive necessary for Black Females by the athletic directors across the divisions, there were several significant factors each division felt experience at that level was crucial. Experience across the divisions was a significant reason, Division I felt experience (p<.00) at this level was significant, while Division II indicated experience at the Division I level as a 3.13, and Division III indicated it as a 2.05. Division II felt experience (p<.00) at this level was crucial, Division I indicated experience at the Division II level as a 2.93, and Division III indicated it as a 2.23. Division III indicated that experience (p<.00) at this level was important but Division I and II did not feel as strongly about experience at the Division III level. Division I indicated experience at the Division III level as a 2.21, and Division II indicated it as a 3.47. Across the divisions education (p<.00) was significant, Division III indicated education as a 4.31, while Division II indicated it as a 4.24, and Division I indicated it as a 3.36. Across the divisions for the athletic directors qualifications (p<.00) was a significant factor, Division I indicated qualifications as a 2.58, while Division II indicated it as a 3.44, and Division III indicated it as a 3.89. For the athletic directors being single (p<.00) was significant, Division I indicated being single as a 1.13, while Division II indicated it as a 1.44, and Division III indicated a 1.00. As indicated by the athletic directors’ (Table 3) strong communication skills, ability to travel/recruit and personality were highly ranked as qualifications perceived necessary. For the commissions (Table 4) Division I experience (p< .01) was significant in the qualifications perceived necessary for Black Females applying for head collegiate basketball positions. Strong communication skills, ability to recruit/travel, and education were essential skills that are necessary for all people to succeed and advance at any level, but they were not significant across the divisions.

DISCUSSION, IMPLICATIONS RECOMMENDATIONS AND APPLICATIONS

Houzer (14) indicated that Black women seem to be becoming less interested and less involved in sports and athletics. On the contrary to what Houzer (14) believed there was no evidence to support the claim. Findings by McGrath (18) noted that sex discrimination was still a major reason for not considering an individual for employment. Baskerville & Tucker (8) felt that racism was used to faze Black women out of leadership positions by imposing the “glass ceiling effect”, which excludes people from the formal settings where careers are made or broken as mentioned previously. Contrary to the research of Houzer (14), McGrath (18) and Baskerville and Tucker (8), race and gender were not indicated as significant factors relating to the qualification perceived necessary by the athletic director across the divisions. Munnings (19) felt that black women are tentative, afraid of rejection, not aggressive, and fearful of the competitive atmosphere of athletics. Hart, Hasbrook & Mathes (1986) indicates that young members of society must have the opportunity to observe a significant number of women in positions of power and status within the sporting world if society is to ever view sports, participation in sports, and sporting careers as unrelated to one’s gender. Throughout the research race, gender, marital status were not significant factors as to why Black females were not applying for open positions. The qualifications the athletic administrators perceived necessary for Black females seeking a head women’s basketball coaching position in Divisions I, II, and/or III were strong communication skills, divisional level experience, education, the ability to recruit/travel and personality. Delano (10) addressed three approaches that can be utilized as means toward solving the lack of representation of Black females in the coaching ranks and addressing many of the underlining preconceived attitudes still present in society. The approaches are the individual level, the micro-structural, and the macro-structural/ideological. The individual level approach includes increasing women’s participation at workshops, increasing their attendance at coaching clinics, and gaining memberships in professional organizations (10). The individual level approach is geared at helping aspiring women become better prepared or more qualified (4) Hart et al. (12). The micro-structural approach suggests strategies aimed at changing established relationships among various people in leadership positions. Examples of the changes include having the same expectations for the women as they do for the men. The approach of embracing change by hiring qualified Black women for coaching positions. Also there must be opportunities to encourage the female athlete to aspire to athletic leadership positions, empowering the Black female athlete as an assistant coach by giving them responsibilities and autonomy (10). Acosta and Carpenter (4) felt that taking the initiative to change administrative structure to make room for Black females in leadership positions was also crucial for their success. The macro-structural ideological analyses approach examined the roots of sexism, racism, classism, and heterosexism all of which underlie the low representation of the Black female in athletic leadership positions. Only when strategies reflect situational differences, the complexities and the depth of the problem will there be an increase in the number of women with diverse backgrounds in athletic leadership positions (10). Recent research by (LaVoi, 2014) indicated several strategies that could be implemented in an attempt to get more females in coaching. One, policy creation such as the concepts of Title IX and the NFL’s Rooney Rule. Strategies as these would involve gender-based approaches when it comes to interviewing, hiring and retaining coaches. Two, another aspect would involve getting more decision-makers, stockholders and other key people in the mix by educating, motivating and exposing them on the trends/issues of women in the coaching profession by highlighting those key aspects associated with the declining numbers (17).

CONCLUSION

The information revealed from the Athletic Administrators relating to the qualifications perceived necessary for Black females to obtain a head coaching position in Divisions I, II, and/or III were; divisional level (I,II,III) experience, education and meeting the stated job qualifications. The top reason that Black females were not applying for the open positions was being unaware of the opening.

With the qualifications perceived necessary identified and the top reason for not applying for open positions also stated, now the objectives are to find ways of getting those items addressed through internships, training programs, hosting opportunity workshop, and the NCAA creating mentoring programs within Women’s collegiate basketball. Until the issue is fully understood and addressed by all involved the opportunities will still remain restricted for some. From the research it indicates that there is more flexibility and understanding evolving from the administrative point of view as it focuses on equality for all. There are qualified Black females who can successfully lead programs at the collegiate level but the opportunities are far and few between. The positive attitudes and intervention must remain the focus, for now and for the future. Based on the research there are avenues that can be taken but everyone must being willing and sincere about opening up those windows of opportunity not just to a few but to all who seek that interaction. There has been considerable advancement in this area but there is still the opportunity and the need to do more.

REFERENCES

- Abney, R., & Richey, D. (1991). Barriers encountered by Black female athletic administrators and coaches. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 61(8), 19-21.

- Abney, R., & Richey, D. (1992). Opportunities for minority women in sports–the impact of Title IX. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 63(3), 56-59.

- Acosta, R., & Carpenter, L. J. (1985b). Women in athletics: Status of women in athletics: Changes and causes. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 56(8), 35-37.

- Acosta, R., & Carpenter, L. J. (1988a). Perceived causes of the declining representation of women leadership in intercollegiate sports—1988 update. Unpublished manuscript, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, New York.

- Acosta, R., & Carpenter, L. J. (1992). As the years go by, coaching opportunities in the 1990s. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 63(3), 36-41.

- Acosta, R., & Carpenter, L. J. (2002). Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal study-25 year update-1977-2002. Unpublished Manuscript Brooklyn College, Brooklyn, New York.

- Acosta, R. & Carpenter, L. J. (2012). Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal, national study thirty-five year update. Retrieved from http://www.acostacarpenter.org

- Baskerville, D., & Tucker, H. (1991, November). Success Blueprint. Black Enterprise, pp. 85-92.

- Brown, Gary (2010). Race and Gender Demographics 2003 – 2009. NCAA News (5/19/2010), p. 1.

- Delano, L. (1990). A time to plant strategies to increase the number of women in athletic leadership positions. Journal of Physical Education and Recreation, 63(3), 53-55.

- Green, C. (1987, February). Women at Work. Black Enterprise, pp. 99-110.

- Hart, B., Hasbrook, C., & Mathes, S. (1986). An examination of the reduction of female interscholastic coaches. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 57(1), 68-77.

- Holmen, M., & Parkhouse, B. (1981). Trends in the selection of coaches for female athletes: A demographic inquiry. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 52(1), 9-18.

- Houzer, S. (1974, December). Black women in athletics. Physical Educator, pp. 208-209.

- Irick, E. (2011, February). Race and Gender Demographics Report 2009 – 2010.

- LaVoi, N.M. (2013, December). The decline of women coaches in collegiate athletics. A report on select NCAA Division-1 FBS institutions, 2012-13. Minneapolis: The Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport. Retrieved from http://umn.edu/womencoaches report.

- LaVoi, N.M. (2014, January). Head coaches of women’s collegiate teams: A report on select NCAA Division-1 FBS institutions, 2013-14. Minneapolis: The Tucker Center for Research on Girls and Women in Sport.

- McGrath, S. (1992, February). Here come the women. Educational Leadership, pp. 62-65.

- Munnings, F. (1990, September). Sidelined the percentage of women in coaching is half what it was 20 years ago. Why? Women’s Sports and Fitness, pp. 40-43.

- NCAA 2008 – 2009 Study in Gender Equity in College Coaching and Administration, 2010.

- Thorngren, C. (1990). A time to reach out: Keeping the female coach in coaching. Journal of Physical Education Recreation and Dance, 61(3), 57-60.