Submitted by JoAnne Barbieri Bullard

ABSTRACT

Goal setting is found to be effective in improving group performance (20, 29). The extent to which athletes engage in goal setting and the effectiveness on mental training elements is beneficial to examine. The purpose of this study was to determine if Division III female student-athletes differed in comparison with each other regarding their previous utilization of goal setting use, to determine if goal setting type was related to intrinsic motivation based on the Sports Motivation Scale (Pelletier, Fortier, Vallerand, Tuson, Briere, & Blais, 1995), to examine if goal setting type was related to group cohesion based on the Group Environment Questionnaire (Brawley, Carron, & Widmeyer, 1987), and to examine if goal setting type was related to goal achievement orientation based on the Task Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (Duda, 1989). The methodology included an informed consent form, demographics questionnaire, goal setting type measurement questionnaire, and data collection from the Sports Motivation Scale, the Group Environment Questionnaire, and the Task Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire. Analyses were completed utilizing bivariate correlations, Chi-square tests, and regression analysis. The results of this study supported group-focused individual goal setting was most primarily used among respondents and also resulted in significant correlations with intrinsic motivation, group cohesion, and goal achievement orientation. Athletic departments and coaching staffs can utilize these findings to coach their student-athletes most effectively.

INTRODUCTION

College athletes continually strive to enhance performance levels through numerous aspects of training. One element that has been deemed effective in enhancing performance and competitive cognitions is that of mental skills training (21, 25, 31). Goal setting is a component of mental skills training found to be effective for enhancing commitment, effort, self-confidence, and perseverance and motivation of athletes (4, 20, 26, 27) although its origins lie in organization settings (12, 15, 16, 28).

Effective goal setting is defined by who sets the goals. Self-set goals initiated by an athlete may be preferred as compared to goals set by others, including coaches and sport psychologists (33). Accepting the goals that are set is necessary for an athlete to be committed to his or her goals and positively affect performance (7, 13).

In a group setting the principles of goal setting have been shown to enhance cooperation, improve morale, and elevate collective efficacy (12). Participation in establishing group goals is correlated with improved group commitment and cohesion (28) and improved group performance with Division I student-athletes (5, 20, 24, 26, 29, 32). Individuals establishing high personal goals compatible with the goals of the group resulted in improved group performance, as compared to individual goals incompatible with the goals of the group, which diminished group performance (15).

Athletes’ intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation affect performance levels through enhancing motivation to accomplish activities, experience stimulation, and to understand a new task (8); through the use of rewards or external constraints and performing behaviors to become socially accepted and avoid negativity (8) and by experiencing feelings of incompetence and an inability to control their actions and consequences (8).

Four variables are responsible for individuals being attracted to groups including group goals, benefits of being a group member, attraction to the group due to affiliation and recognition, and comparison with other groups (17). Cohesion enhances productivity in team sports due to communication and teamwork improvement (34). Reducing the amount of motivation loss in teams enhances commitment, goal contribution, and productivity (34).

Individuals are identified according to two orientations based on their achievement abilities (18). Task orientation involves an individual establishing goals with the intention to master a skill, whereas ego orientation involves an individual feeling successful after outperforming others (18). Male and female Division III athletes with elevated levels of task orientation were more likely to have a greater sense of awareness resulting in increased performance and ability to master tasks as compared to those with elevated ego orientations (18). Ego orientated individuals had elevated levels of aggression and anxiety and lower levels of satisfaction (18). Although intrinsic motivation was related to having higher levels of task orientation, inclusion of goal setting was not found (18). It was therefore necessary to examine if Division III female athletes’ goal setting type was related to intrinsic motivation levels.

One aspect of research led to the belief that utilizing group-focused goals results in improved individual and group motivation and enhanced group performance in industrial-organizational settings (12). However, the use of group-focused individual goals within an athletic setting had not been assessed. The need to determine if goal setting type was related to student-athletes’ intrinsic motivation levels through examining the effects of previous use of goal setting is apparent.

Differences exist between athletes in their implementation of goal setting practices determining effectiveness (30). In a team atmosphere, individual athletes must work towards achieving their personal goals, as well as their team goals in order to be successful. It was possible that Division III female athletes exhibited varied goal setting type usage compared to each other.

Athletes setting team goals are found to have elevated perceptions of cohesion at the end of their season compared to the athletes who did not establish goals (24). It was thought that through having athletes develop team goals individually; each member’s feelings of involvement with the team would be enhanced (24). It was not identified if group-focused individual goal setting would impact cohesion (24). This is why it was necessary to examine if Division III female athletes’ goal setting type was related to group cohesion.

Methods

Participants

The target population of this study was Division III female student-athletes. The 76 student-athletes were members of the women’s field hockey, softball, basketball, soccer, volleyball, cross country, crew, tennis, and track and field teams. Out of the total sample size, 42 were off-season student-athletes and 34 were in-season student-athletes.

Instrumentation

Demographic information and consent. To conduct this study, each participant received an informed consent form acknowledging their volunteer participation in the study. To avoid collecting information that would identify each individual, participants were asked to report their year of education and year of participation rather than their specific age. The choices for education year included: Freshman, Sophomore, Junior, and Senior. The choices for participation year included: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th. The demographic information included: year of education; year of participation; transfer student status; sport(s) in which they participate; in-season or off-season athlete status; status as a starter or non-starter in most recent season; and individual or team sport athlete status.

Goal setting type measurement questionnaire. The three types of goal setting identified in this study were group goals, individual goals, and group-focused individual goals. In order to identify goal setting type, participants were asked to rate 18 questions (30) regarding goal setting frequency, goal setting effectiveness, goal setting effort, and goal setting barriers using a 7-point Likert scale. Participants were informed that for this study goal setting referred to the use of specific, measurable goals assisting in achieving performance measures. Overall goal frequency, overall goal effectiveness, overall goal effort, and overall ability to reach goals were also observed with this questionnaire.

Overall goal setting frequency, referring to how often participants used goal setting strategies, was assessed on responses to nine questions based on a 7-point Likert scale. Goal setting effectiveness, or the effectiveness of specific goal setting strategies, was assessed based on the responses of a 7-point Likert scale. Three questions examined overall goal setting effort based on the amount of effort participants put forth to achieve goals in specific situations and was assessed by the responses to three statements based on a 7-point Likert scale. The overall ability to reach goals was evaluated based on three questions using a 7-point Likert scale and was measured by interfering factors participants experienced.

For the purpose of this study, the goal setting type category with the highest mean value of responses was identified as the goal setting type for each student-athlete. This measurement illustrated the degree to which participants utilized or did not utilize other types of goal setting. Three questions were developed based on the definition for group goal setting, individual goal setting, and group-focused individual goal setting.

Sport Motivation Scale (SMS) (Pelletier et al., 1995). The SMS measures intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation of athletes through the use of seven subscales (10) including: intrinsic motivation to know, to accomplish things, and to experience satisfaction; extrinsic motivation of external, introjected, and identified regulation; and amotivation in reference towards sport participation (19). The SMS includes four items from each subscale totaling 28 items on the scale (11).

Participants responded to each item on a seven point Likert scale, ranging from not corresponding at all to corresponding exactly (19). An index of self-determined motivation is established after the subscales were combined (8). Athletes with high positive scores have elevated levels of sport self-determined motivation and low scores reflecting low self-determined motivation (8). Internal reliability ranged from .72 to .85 for present motivation and for perceived future motivation from .67 to .86 (19). For the purpose of this study, only intrinsic motivation from this scale was utilized to answer the 12 intrinsic motivation questions.

Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ) (Brawley et al.,1987). The GEQ assessed perceived cohesion through the use of an 18-item, four scale instrument (3). Four components of cohesion are measured identifying a member’s attraction to the group-task (ATG-T), a member’s attraction to the group-social (ATG-S), a member’s integration into the group-task (GI-T); and a member’s integration into the group-social (GI-S) (17). Internal consistency values were r= .75, .64, .71, and .72 respectively (3). Responses for this questionnaire were based on a 9-point Likert scale (24). Nine questions referred to participants’ personal involvement with the team and nine questions referred to participants’ perceptions of their team as a whole. Participants’ scores were tallied based on each of the four variables to assess overall group cohesion. The odd numbered questions referred to the social aspects of cohesiveness, whereas the even numbered questions referred to task aspects of cohesiveness. An average was taken for each component (ATGS, GIS, ATGT, and GIT) after being summed for each participant.

Task Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (TEOSQ) (Duda, 1989). The TEOSQ assessed differences in an individual’s proneness for task or ego goal orientation in athletic settings (14). This questionnaire consisted of 13 sport specific questions, which are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (18). Participants were asked to consider the phrase “I feel most successful in sport when…” prior to answering the questions (18). Overall task orientation and ego orientation resulted by averaging the total responses of each category for all participants. The TEOSQ has an alpha reliability coefficient of .62 for task orientation scale and .85 for ego orientation scale was present (9) and reported internal reliability of .80 for task orientation and .75 for ego orientation (10).

Results and Discussion

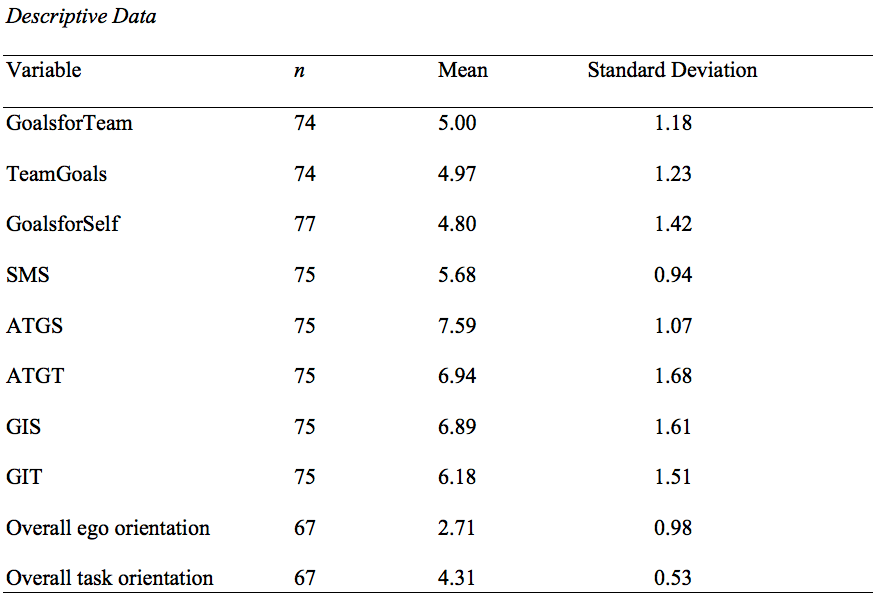

There were 76 participants of the Division III female student-athlete population (n=76). All participants received identical questionnaire packets in which they were asked to volunteer to respond to each questionnaire honestly. Two participants neglected to answer all the questions of the goal setting type measurement questionnaire, resulting in these subjects’ responses being omitted from the analyses involving these assessments. For the both the SMS and the GEQ one participant did not complete all the questions, resulting in exclusion. Four participants skipped a question on the TEOSQ, while five participants answered one question twice, resulting in the omission from this questionnaire in the data analysis (n=67). Table 1 depicts the descriptive data of the variables assessed throughout the questionnaires.

Demographic Questionnaire

Education year and participation year. Of the 76 participants, 27.6% indicated being a freshman, 43.4% indicated being a sophomore, 17.1% indicated being a junior, and 11.8% indicated being a senior. In regard to participation year, 35.5% indicated being in their 1st year of participation, 36.8% indicated being in their 2nd year of participation, 19.7% indicated being in their 3rd year of participation, and 7.9% indicated being in their 4th year of participation.

Transfer. A total of 11 (14.5%) participants identified as being a transfer student, whereas 65 (85.5%) identified as never having transferred.

Sports. Of the student-athletes in this population, 23 identified as softball athletes, followed by 17 soccer athletes, 10 basketball athletes, nine volleyball athletes, five field hockey athletes, and three track and field athletes. Nine of the participants were dual athletes, participating in more than one sport.

Current Season. Out of the 76 participants, 44.7% identified themselves as in-season athletes, whereas 55.3% identified themselves as off-season athletes.

Starter. Out of the 76 participants, 42 (55.3%) identified as being a starter, while 34 (44.7%) identified as being a non-starter.

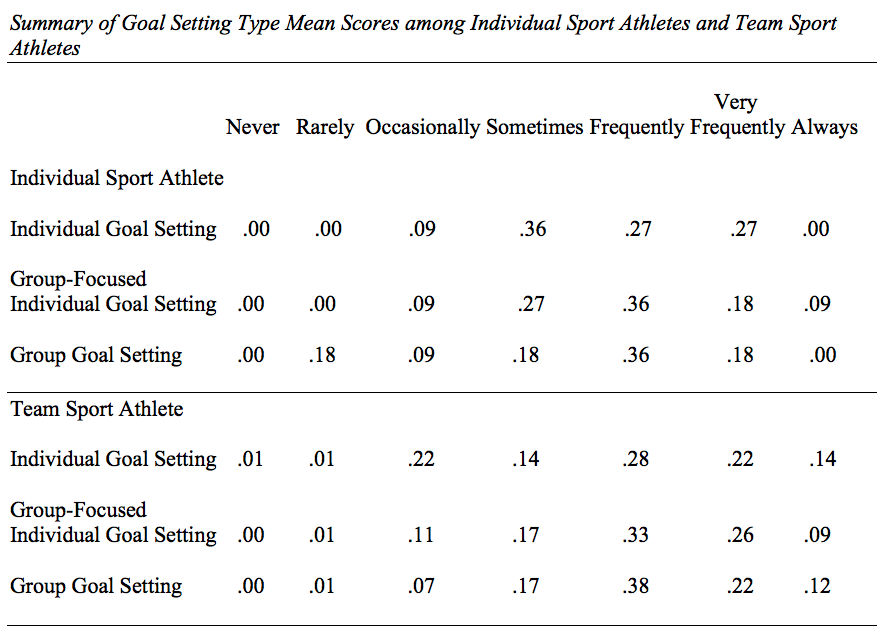

Sport Classification. The majority of the participants (85.5%) identified as being a team-sport athlete, whereas 14.5% identified as being an individual-sport athlete. Differences in goal setting type among individual sport athletes and team sport athletes are depicted in Table 2.

Goal Setting Type Measurement Questionnaire

The results of this questionnaire assisted in answering if participants differed in comparison with each other regarding their previous utilization of goal setting type. Two participants were omitted from this section of the study since they did not completely answer the questionnaire, resulting in a sample of 74. The mean and standard deviation for these questions are shown in Table 1. A repeated measures ANOVA showed there was no statistically significant difference among the three goal setting types. Wilks’ Lambda = .974, F(2,27) = .98, p =.38.

Sport Motivation Scale (SMS)

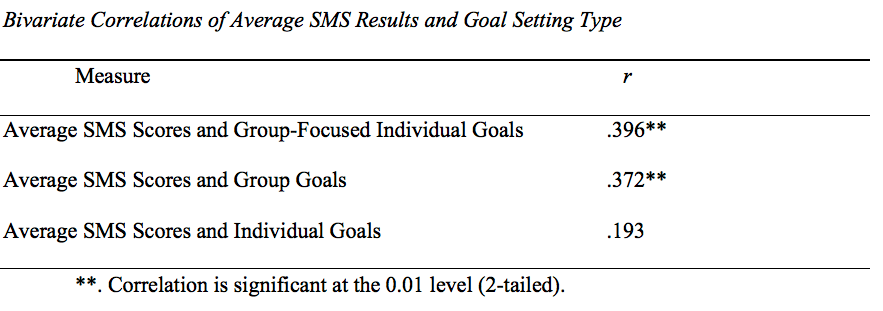

The sample size for the SMS was 75 since one participant did not complete the questionnaire. Table 1 depicts participants’ mean and standard deviation results based on the average SMS scores. The three goal setting types evaluated were individual goal setting, group-focused individual goal setting, and group goal setting. A bivariate correlation analysis, depicted in Table 3, was utilized to compute the Pearson’s correlation coefficient and significance levels to measure relationships among intrinsic motivation scores and levels of each goal setting type. The total number of participants examined was 73 since three participants did not fully complete the goal setting type measurement questionnaire. The Pearson correlation calculation resulted in a positive value and relationship between SMS scores and group-focused individual goals and group goals.

Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ)

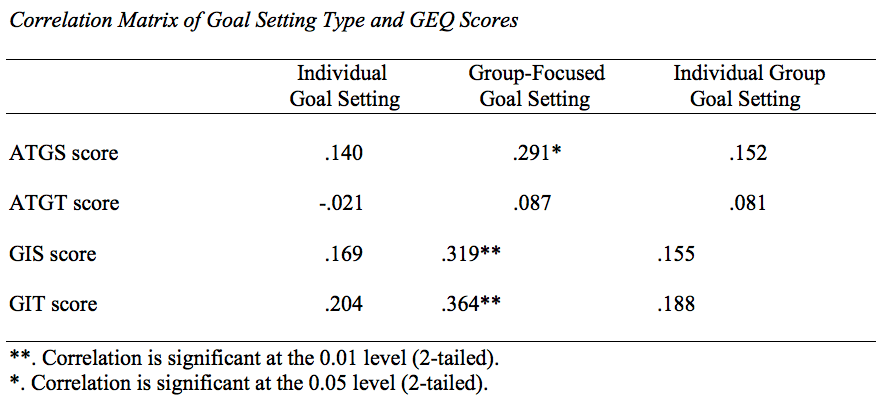

Seventy-five participants completed the GEQ assessing the perceived cohesion of their teams by indicating the level of agreement with each statement. Table 1 provides the participants’ ATGS, ATGT, GIS, and GIT mean and standard deviation scores based on the GEQ. A Bivariate correlation analysis was utilized to determine the relationship among goal setting type and group cohesion variables through the use of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient and significant levels. Significant correlations at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) were found between group-focused individual goal setting and both GIT score and GIS scores. A significant correlation at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) was found between group-focused individual goal setting and ATGS score, shown in Table 4.

Task Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (TEOSQ)

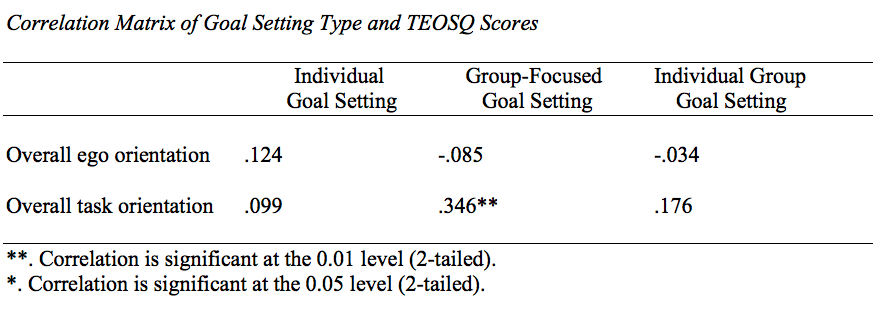

The TEOSQ was utilized to assess goal orientation in an athletic environment. Participant size was limited to 67 since nine participants did not complete the questionnaires. Table 1 presents participants’ average task orientation and ego orientation mean and standard deviation scores based on the TEOSQ. A Bivariate correlation analysis was utilized to determine the relationship among goal setting type and goal orientation achievement. Through the use of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient and significance levels, the relationship was determined based on the 66 participants since one participant did not fully complete this questionnaire. The results of this analysis showed one significant positive correlation between overall task orientation and group-focused individual goal setting on the 0.01 level (2-tailed), depicted in Table 5.

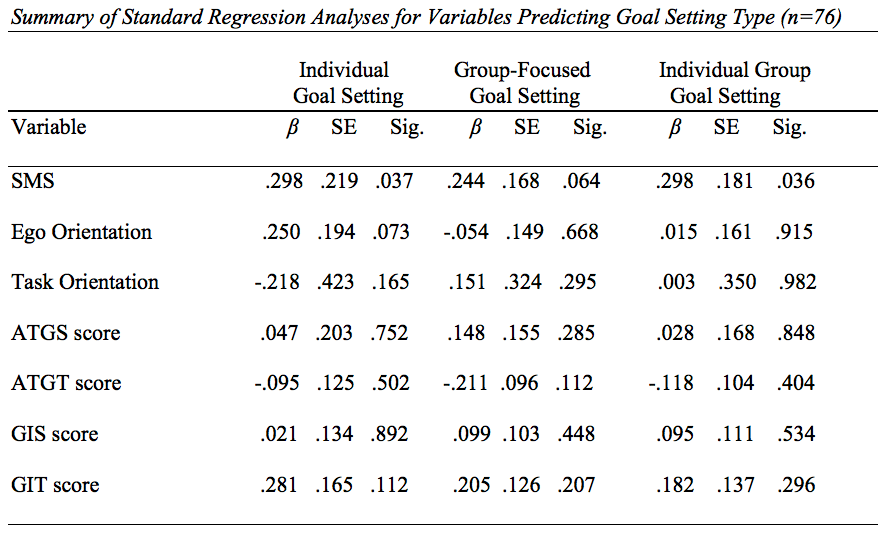

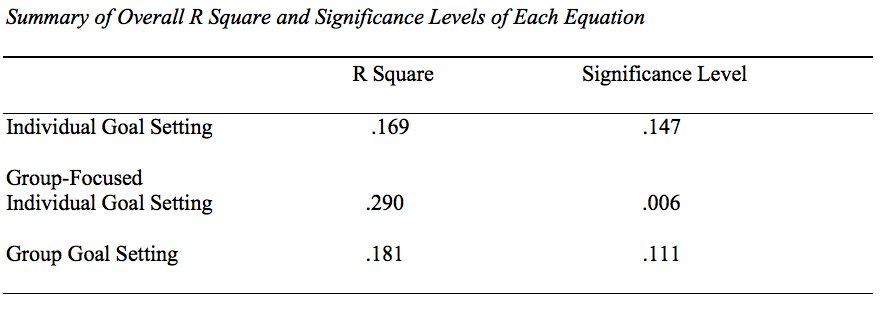

A standard regression analysis was conducted for each of the goal setting types using SMS, ego orientation, task orientation, ATGS score, ATGT score, GIS score, and GIT score as predictors, shown in Table 6. Group-focused individual goal setting was found to have the largest R squared value (.290) with SMS being the most significant predictor. Individual goal setting type was found to have the weakest positive correlation between predictor and criterion variables, shown in Table 7.

CONCLUSIONS

In an attempt to determine if goal setting type usage differed among respondents, the goal setting type measurement questionnaire was utilized. Respondents were found to frequently utilize all three of the goal setting types according to the overall mean scores of goal setting type use. Results indicated no difference in how frequently this sample of student-athletes used the three types of goal setting as indicated by the repeated measures ANOVA. The frequency of goal setting use among Division III female student-athletes showed that goal setting is a common practice among these athletes consistent with previous research (5, 7; 22, 29, 32, 30).

The SMS was utilized to determine if goal setting type was related to the respondents’ intrinsic motivation levels. Approximately 57.3% of the respondents’ levels of intrinsic motivation resulted above the mean score of 5.68 which was related to “corresponding a lot” in regard to intrinsic motivation based on their previous season. This supports findings regarding intrinsic motivation positively influencing participation frequency, commitment, and effort (4) in that 53% of the respondents frequently utilized goal setting practices.

Significant correlations at the 0.01 level resulted among both group-focused individual goal setting and group goal setting, whereas individual goal setting presented a weaker positive value at the 0.05 level. Respondents with elevated levels of intrinsic motivation were most likely to utilize group-focused individual goals, followed by group goals. This supported correlations between female athletes utilizing process goals and increasing motivation (26). Results indicated that goal setting type was related to this sample of athletes’ intrinsic motivation levels based on the SMS.

Respondents’ levels of cohesion were measured through the use of the GEQ to assess four variables including ATGS, ATGT, GIS, and GIT. The ATGS score, referring to respondents’ individual attractions to the group, resulted with the highest mean score. These findings support the research regarding higher levels of cohesion and involvement of groups in decision making and satisfaction (3).

ATGS score, GIS score, and GIT score were found to have a significant correlation with group-focused individual goal setting. Results indicated that group-focused individual goal setting type related to this sample of athletes’ group cohesion levels supporting previous research indicating that cohesion is found to be intricate in group goal setting and goal acceptance (3).

Athletes with high task orientation and moderate ego orientation have been found to utilize goal setting more than those with other goal orientation combinations (10). After analyzing the TEOSQ it was concluded that mean task orientation scores (4.31) were larger than mean ego orientation scores (2.71). Overall task orientation was found to have a significant correlation at the 0.01 with group-focused individual goal setting (0.346). These results showed that the respondents with higher task orientation scores had significant relationships with goal setting practices as compared to overall ego orientation scores of the respondents (9). Results indicated that group-focused individual goal setting was related to this sample of athletes’ goal achievement orientation based on the TEOSQ.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

This research study contributes to the field of sport psychology. The information gathered throughout this study will help athletic departments and the coaching staffs by providing information that can be utilized to assist female student-athletes with using goal setting practices beneficial for themselves and their teams. The results of this study provided insight regarding the additional variables such as intrinsic motivation, group cohesion, and goal achievement orientation that impact goal setting and may inspire future research of the impact on Division III male student-athletes and other divisions of female student-athletes. Group-focused individual goal setting was the only goal setting type significantly correlated to all three variables; intrinsic motivation, group cohesion, and goal achievement orientation. These results showed that athletes utilizing group-focused individual goals are more likely to enhance intrinsic motivation levels, group cohesion levels, and goal achievement orientation as compared to athletes utilizing individual goal setting or group goal setting practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None

REFERENCES

1. Alexandris, K., Tsorbatzoudis, C., & Grouios, G. (2002). Perceived constraints on recreational sport participation: Investigating their relationship with intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation. Journal of Leisure Research, 34(3), 233-252.

2. Brawley, L., Carron, A., & Widmeyer, W. (1987). Assessing the cohesion of teams: Validity of the group environment questionnaire. Journal of Sport Psychology, 9(3), 275-294.

3. Brawley, L., Carron, A., & Widmeyer, W. (1993). The influence of the group and its cohesiveness on perceptions of group goal-related variables. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 15(3), 245-260.

4. Burton, D., & Weiss, C. (2008). The fundamental goal concept: The path to process and performance success. In T. S. Horn, T. S. Horn (Eds.), Advances in sport psychology (3rd ed.) (pp. 339-375, 470-474). Champaign, IL US: Human Kinetics.

5. Burton, D., Weinberg, R., Yukelson, D., & Weigand, D. (1998). The goal effectiveness paradox in sport: Examining the goal practices of collegiate athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 12(4), 404-418.

6. Duda, J. L. (1989) The relationship between task and ego orientation and the perceived purpose of sport among high school athletes. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11, 318-335.

7. Fairall, D., & Rodgers, W. (1997). The effects of goal-setting method on goal attributes in athletes: A field experiment. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 19(1), 1-16.

8. Gillet, N., Berjot, S., & Gobance, L. (2009). A motivational model of performance in the sport domain. European Journal of Sport Science, 9(3), 151-158.

9. Hanrahan, S., & Biddle, S. (2002). Measurement of achievement orientations: Psychometric measures, gender, and sport differences. European Journal of Sport Sciences, 2(5), 1-11.

10. Kim, M., Duda, J., & Gano-Overway, L. (2011). Predicting occurrence of and responses to psychological difficulties: The interplay between achievement goals, perceived ability, and motivational climates among Korean athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(1), 31-47.

11. Kingston, K., Horrocks, C., & Hanton, S. (2006). Do multimensional intrinsic and extrinsic motivation profiles discriminate between athlete scholarship status and gender? European Journal of Sport Science, 6(1), 53-63.

12. Kleingeld, A., Van Mierlo, H., & Arends, L. (2011). The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1289-1304.

13. Kyllo, L., & Landers, D. (1995). Goal setting in sport and exercise: A research synthesis to resolve the controversy. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 17(2), 117-137.

14. Li, F., Harmer, P., Chi, L., & Vongjaturapat, N. (1996). Cross-cultural validation of the task and ego orientation in sport questionnaire. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 18(4), 392-407.

15. Locke, E., & Latham, G. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265-268.

16. Lycette, B., & Herniman, J. (2008). New goal-setting theory. Industrial Management, 50(5), 25-30.

17. Matheson, H., Mathes, S., & Murray, M. (1997). The effect of winning and losing on female interactive and coactive team cohesion. Journal of Sport Behavior, 20(3), 284-298.

18. McCarthy, J. (2011). Exploring the relationship between goal achievement orientation and mindfulness in college athletics. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 5(1), 44-57.

19. Medic, N., Mack, D., Wilson, P., & Starkes, J. (2007). The effects of athletic scholarships on motivation in sport. Journal of Sport Behavior, 30(3), 292-306.

20. Mooney, R., & Mutrie, N. (2000). The effects of goal specificity and goal difficulty on the performance of badminton skills in children. Pediatric Exercise Science, 12(3), 270-283.

21. Myers, A., Whelan, J., & Murphy, S. (1996). Cognitive behavioral strategies in athletic performance enhancement. Progress in Behaviour Modification, 30, 137-164.

22. O’Brien, M., Mellalieu, S., & Hanton, S. (2009). Goal-setting effects in elite and nonelite boxers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21(3), 293-306.

23. Pelletier, L., Fortier, M., Vallerand, R., Tuson, K., Briere, N., & Blais, M. (1995). Toward a new measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation in sports: The sports motivation scale (SMS). Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 17(1), 35-53.

24. Senecal, J., Loughead, T., & Bloom, G. (2008). A season-long team-building intervention: Examining the effect of team goal setting on cohesion. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 30(2), 186-199.

25. Vealey, R. (1994). Current status and prominent issues in sport psychology interventions. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 26(4), 495-502.

26. Vidic, Z., & Burton, D. (2010). The roadmap: Examining the impact of a systematic goal-setting program for collegiate women’s tennis players. The Sport Psychologist, 24(4), 427-447.

27. Vosloo, J., Ostrow, A., & Watson, J. (2009). The relationships between motivational climate, goal orientations, anxiety, and self-confidence among swimmers. Journal of Sport Behavior, 32(3), 376-393.

28. Wegge, J. (2000). Participation in group goal setting: Some novel findings and a comprehensive model as a new ending to an old story. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49(3), 498-516.

29. Weinberg, R., Burton, D., Yukelson, D., & Weigand, D. (1993). Goal setting in competitive sport: An exploratory investigation of practices of collegiate athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 7(3), 275-289.

30. Weinberg, R., Burton, D., Yukelson, D., & Weigand, D. (2000). Perceived goal setting practices of Olympic athletes: An exploratory investigation. The Sport Psychologist, 14(3), 279-295.

31. Weinberg, R., & Comar, W. (1994). The effectiveness of psychological interventions in competitive sport. Sports Medicine, 18(6), 406-418.

32. Weinberg, R., Stitcher, T., & Richardson, P. (1994). Effects of a seasonal goal-setting program on lacrosse performance. The Sport Psychologist, 8(2), 166-175.

33. Weinberg, R., & Weigand, D. (1996). Let the discussions continue: A reaction to Locke’s comments on Weinberg and Weigand. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 18(1), 89-93.

34. Williams, J., & Widmeyer (1991). The cohesion-performance outcome relationship in a coacting sport. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 13(4), 364-371.