Submitted by Lorraine Killion, Ed.D. & Dean Culpepper, Ph.D.

ABSTRACT

Body image is a complex synthesis of psychophysical elements that are perpetual, emotional, cognitive, and kinesthetic (1). The desire to achieve and maintain an ideal weight is a prevalent goal among females. The purpose of this study was to examine a female population of competitive dancers, control, and fitness cohorts’ body image and eating characteristics. A total of 51 (29 dancers, 12 control, and 10 fitness) subjects completed the MBSRQ-AS, EAT-26, a Physical Activity Questionnaire, Stunkard Figural Silhouettes, and body fat measurements. A MANOVA was conducted to determine group differences and showed a significant relation (Wilk’s Lambda = .106, F=8.735, p<001). Post hoc tests were conducted to determine directionality and showed that the dancers scored significantly higher on the Appearance Orientation subscale (p=.034) with no difference between the control and fitness cohort. Dancers also significantly perceived themselves to be overweight (p=.048) with no difference between the other two groups. Both the dancers (p<.001) and the fitness cohort (p<.001) scored as exhibiting disordered eating patterns as rated by the EAT-26. Even though the dancers had a low percent body fat (M=17.6), they tended to place more importance on how they look. The dancers perceived themselves to be overweight and engaged in disordered eating patterns. These types of perceptions and behaviors are disturbing, but not surprising since dancers have a drive for thinness to compete (2). To fully understand the scope of the issue and the psychological factors that accompany the quest for achieving a certain appearance, future research should include other female cohorts such as elite athletes, obligatory exercisers, and sedentary females to determine any similarities and differences in the groups.

INTRODUCTION

Research has documented and quantified a shift towards a thinner ideal shape for females in the Western culture for the past 20 years (3). Body image has been shown in numerous studies to be a key issue for females. Body image has been described as a multidimensional construct that describes internal, subjective representations of physical and bodily appearance (4). The internal representations of one’s own body include both cognitive and perceptual elements (5). In addition, eating disorders have been shown to be prevalent in females with more than 90 percent of those with eating disorders are women between the ages of 12 and 25 years of age (6, 7, 8). Research indicates that both of these factors (body image and eating disorders) are present among elite performers of certain sports or physical activities, ballet dancers, and professional dancers (8). Yet little has been reported on dance team participants (9, 10, 11).

Dance team is difficult to research due to the paucity of literature available and the complexity of terminology. Also, dance team is a nebulous term to define. Research demonstrates common referrals to spirit teams, spirit squads, dance teams, as well as pom squads. While the confusion in labeling and current argument as to whether this is an activity or a sport still looms, one fact that remains constant is competitive spirit teams is one of the fastest growing areas of participation for females (12).

Among high school participants, over 96,718 females were accounted for in the 2010-2011 high school athletics participation survey conducted by the National Federation of State High School Associations, ranking competitive spirit teams ninth for female participation. At the college level, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) reported that spirit squad has experienced the most growth for women’s sport (13, 14). A nationwide Division I study conducted during the 2001-02 academic school year investigated the prevalence of dance and cheerleading programs and reported 89% of the institutions contacted indicated they sponsored competitive dance (12).

The current emerging phenomenon of dance teams has witnessed the rise in visibility of participants at sporting events and are known for their pre-game and half-time routines. Dance teams are comprised of competitive dancers who are required to practice for long hours in movements, choreography, and synchronicity among dancers. Participants are also required to incorporate specific choreography (i.e., contemporary, hip-hop, or jazz) and technical skills (jumps, kicks, and other gymnastic-type skills) into the routine. It is highly competitive and requires hours of rehearsal to master precise movements in harmony with other members of the team.

The increasing number of females participating in dance team competition is prevalent. Long rehearsal hours, use of mirrors, and dance outfits, place dance team participants at risk of body image concerns (15, 16, 17, 18). Of additional concern is the presence of wearing dance outfits which possibly place them as subjects of objectification, or being evaluated by gazing or being observed or “checked out” on the basis of their appearance (17, 19, 10).

With the growing number of females participating in dance team competition, a further examination of the psychosocial factors that accompany this new sport warrants investigation including the importance of assessing potential body image disturbance. This study was designed to examine the perceptions of dance team participants, fitness participants, and non-dancers in a college population.

METHODS

Upon Internal Review Board (IRB) approval, fifty one subjects were recruited from two university campuses. Informed consent was obtained prior to the study through an information letter that was administered to participants in dance and physical fitness classes.

Participants

Participants were female students enrolled in university classes and dance teams. Two university campuses were involved in the study and yielded a total of 51 participants. The study was comprised of 29 dancers, 10 fitness students, and 12 control subjects. The mean age and standard deviation for the participants were: dancers (M = 20.69, SD = 2.25), fitness (M = 25.40, SD = 8.67), and control (M = 20.42, SD = 0.996). The dancers were from university dance teams, the fitness participants were enrolled in fitness classes, and the participants in the control group were randomly selected from general university courses.

Instruments

Each subject completed questionnaires assessing participant demographics, physical activity involvement using the NASA Physical Activity Scale and body image perceptions using the Stunkard Figural Rating Silhouettes. Eating behavior patterns were assessed utilizing the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) and attitudes concerning body image were assessed with the Multi- dimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ). Anthropometric measurements (height and weight) were then taken. Weight was taken using a Tanita WB-110A Digital Scale and height was taken using a using a Seca 420 measuring stadiometer. Body fat measurements were taken on each participant using an Omron Fat Loss Monitor, Model HBF-306C. The Fat Loss Monitor (Omron Fat Loss Monitor, Model HBF-306C) displays the estimated value of body fat percentage by bioelectrical impedance method and indicates the Body Mass Index (BMI). The bioelectrical impedance, skinfold, and hydrostatic weighing methods have all been shown to be reliable measures of body composition (r = .957-.987). (23)

Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26)

The Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) was used to differentiate participants with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating, and those without disordered eating characteristics. It is a 26-item measurement consisting of three subscales: 1) dieting, 2) bulimia and food perception, and 3) oral control. Scoring for this instrument was a Likert scale of six possible answers (always, usually, often, sometimes, rarely, never). Scores ranged from zero to three for each question and a total score greater than 20 indicates excessive body image concern that may identify an eating disorder (20, 21). The EAT-26 has been proven to be a reliable (r =.88) measurement. (7)

Figural Rating Silhouettes

Body size judgments were obtained using the Stunkard Figure Rating Scale (see figure 1). This scale consists of a nine-figure scale of numbered silhouettes that increase gradually in size from very thin (a value of 1) to very obese (a value of 9). (22) Two body size perception variables were included in the current study. “Self-perceived body size” is the number of the figure selected by participants in response to the prompt “Choose the figure that reflects how you think you currently look.” “Ideal body size” is the number of the figure chosen in response to the prompt “Choose your ideal figure.” This scale has good test-retest reliability and adequate validity (23, 24). Following the methods of other investigators, we defined body size satisfaction as the difference between self-perceived body size and ideal body size (25, 26, 27, 28). A body size discrepancy index variable was created for each participant by subtracting the number of the figure selected as the ideal body size from the number of the figure selected as the self-perceived current body size (28). A high body size discrepancy value signifies low satisfaction with body size, and a low value signifies greater satisfaction with body size.

Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire

The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) is a 69 item self-report inventory for the assessment of self-attitudinal aspects of the body image construct. The MBSRQ measures satisfaction and orientation with body appearance, fitness, and health. In addition to seven subscales (Appearance Evaluation and Orientation, Fitness Evaluation and Orientation, Health Evaluation and Orientation, and Illness Orientation), the MBSRQ has three special multi-item subscales: (1) The Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS) approaches body image evaluation as dissatisfaction-satisfaction with body areas and attributes; 2) The Overweight Preoccupation Scale assesses fat anxiety, weight vigilance, dieting, and eating restraint; and 3) The Self-Classified Weight Scale assesses self-appraisals of weight from “very underweight” to “very overweight.” Internal consistency for MBSRQ subscales range from .74 -.91. This questionnaire has been studied and used extensively in the college population. Internal consistency for the subscales of the MBSRQ ranged from .67 to .85 for males and .71 to .86 for females (9).

Physical Activity Scale

Level of physical activity was obtained by self-report with the NASA Activity Scale (NAS) (29, 30). The scale enables subjects to rate their general activity behavior over the previous 30 days. The scale range is from 0 to 10, which is based on the total weekly minutes spent in exercise or the total weekly miles run or walked. A NAS of 0-1 represents very low activity. A rating of 2-3 represents regular recreation or work of modest effort in such activities as golf or yard work for a weekly total of between 30 min to 2 h. Ratings of 4-10 represent regular participation in aerobic exercise ranging from light to heavy exercise.

Procedures

The participants were instructed by a trained individual to fill out the information packets provided on clipboards. First, the participants completed a personal identification and demographic sheet that contained general information such as age and dance or sport category. The participants then completed the MBSRQ-AS, the EAT-26, Physical Activity Questionnaire, and the Stunkard Figural Rating Scale (31, 20, 29, 22). As the participants completed the written component of the study, another trained individual took height and weight measures of the participants and recorded the body mass index (BMI) from a hand-held BIA analyzer. Weight was taken using a Tanita WB-110A Digital Scale and height was taken using a using a Seca 420 measuring stadiometer. A test/retest method was utilized for both measures to offset measurement error. In the measure of weight, the individual’s weight was recorded, the participant stepped off the digital scale and the scale was returned to “zero”. The measure was then taken again and recorded. In the measure of height, the same procedure of test/retest was used. When all measures were taken, the average of the two measures was then recorded. The measures were then taken by the researchers and converted using the formula (BMI = weight/height M2). BMI was then calculated and recorded for all participants. When the information was completed, the participants returned the packets to the trained administrator. Data sheets were collected and kept in a locked file cabinet for confidentiality.

A total of 51 participants completed the MBSRQ-AS, EAT-26, a Physical Activity Questionnaire, Stunkard Figural Silhouettes, and body fat measurements. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The Dancers and the Fitness group were significantly lower in body fat and higher in physical activity and the on the EAT-26. A MANOVA was conducted to determine group differences among the different measures and the subscales.

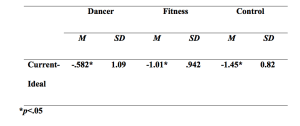

Table 1 – Figure Rating Means for each Group (dancer, fitness, & control)

RESULTS

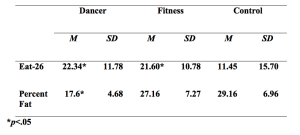

The MANOVA indicated a significant relation (Wilk’s Lambda = .106, F = 8.735, p<.001). Post hoc tests were conducted and analyses were examined to determine directionality. Results showed that the dancers scored significantly higher on the Appearance Orientation subscale (p=.034) with no difference between the control and fitness cohort. Dancers also significantly perceived themselves to be overweight (p=.048) with no difference between the other two groups. Both the dancers (p<.001) and the fitness cohort (p<.001) scored as exhibiting disordered eating patterns as rated by the EAT-26 (see Table 2).

Even though the dancers had a low percent body fat (M=17.6), they tended to place more importance on how they look. Body dissatisfaction measures often focus on body build and are operationalized as the difference between ideal and self-perceived current figure as selected from a group of drawings (32, 33, 34). Measures of body dissatisfaction were computed by subtracting participants’ ratings of their Current Body Size (CBS) from their Ideal Body Size (IBS) to create a discrepancy index (DI). (28) The DI’s for each group were calculated with means and standard deviations recorded: Dancers (-.59/1.11), Fitness Group (-1.04/.966), and Control (-1.55/.85). The dancers in this study were dissatisfied with their bodies and wanted a thinner body as described in the discrepancy index, indicating a higher level of importance on their appearance (p=.045).

Table 2-Percent Fat and Eat-26 Totals for Subjects

DISCUSSION

The primary focus of this investigation was to examine collegiate dance team participants to see if they exhibited body image distortions and disordered eating habits as exhibited in other female performers. Even though the dancers had a low percent body fat (M = 17.6), they tended to place more importance on how they look. The dancers perceived themselves to be overweight and engaged in disordered eating patterns. These types of perceptions and behaviors are disturbing, but not surprising since dancers have exhibited a drive for thinness to compete (2).

The findings of the data for this study are consistent with previous studies regarding body image in females (6, 35, 36). The females in this study perceived their current figure as heavier than their ideal figure. Although literature available on dancers exists, many of the studies have focused on ballet dancers and other professional dancer types. Future research should examine dance team participants to see if the pressures are similar (i.e., rehearsing with mirrors and being viewed during their performance by an audience). To fully understand the scope of the issue and the psychological factors that accompany the quest for achieving a certain appearance, future research should include other female cohorts such as elite athletes, obligatory exercisers, and sedentary females to determine any similarities and differences in the groups.

These results indicate that dancers had higher incidence of negative body image disturbances as compared with the controls. Dancers are usually expected to be slim, well-proportioned, and toned and are placed under a great deal of pressure to maintain these features. Often, the various aspects of a dance class can potentially lead to a negative body image (37). The pressures of being thin may present negative body images for dance team members (38). A national survey conducted reported that body image concerns continue to be prevalent among American women (39). Levels of body dissatisfaction may also foster negative affect because appearance is a central dimension for women in our culture (40).

While the dangers of distorted body image are present in the dance world, measures to minimize their impact should include coaches who focus on performance rather than personal appearance. Taking an active interest in how their dancers view themselves is critical to a more comprehensive understanding of the causes of body image concern. By further addressing this issue, researchers can also help minimize health risks in female participants as well as reduce body image dissatisfaction.

Limitations & Implications

Limitations to this study include the sample size. In addition, this study investigated indicators of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors rather than clinical diagnoses of eating disorders. Other variables that are contributing factors to the prevalence of disordered eating were not investigated. The results of the EAT-26 test were not intended to diagnose nor suggest an eating or life-threatening disorder; however, the EAT-26 was used because it has proven to be an effective screening tool in identifying eating disorder symptomology and allows for further investigation for treatment.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

Body image has been the subject of much research conducted in recent years. As a result, body image is now recognized a multidimensional construct with complex aspects, particularly perceptual. The majority of the existing data indicates that body image concerns are prevalent among American females. With the recent phenomenal growth of dance team participation and the increasing number of female participants; a closer examination is warranted. Yet, there is a paucity of research available on dance team participants and their perceptions of their body appearance. Because dance team members wear a designated uniform/outfit, dance to a learned synchronized routine, and perform in front of an audience, they are subjected to visual scrutinization of fans/viewers. The uniqueness of the stressors and demands placed on the dancers complicates this issue. Additional knowledge of how dance team members perceive how they look and what the audience thinks of them in regards to abilities and their physical appearance deserves further investigation. Dealing with such information will not only benefit dance team members body image and self-esteem, but assist coaches and directors in ways to assist young women in resulting body image dissatisfaction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None

REFERENCES

1. Thompson, K. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

2. Wood, K. C., Becker, J. A., & Thompson, J. K. (1996). Body image dissatisfaction in preadolescent children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 17, 85-100.

3. Garner, D. M., Garfinkel, P. E., Schwartz, D., and Thompson, M. (1980). Cultural

expectations of thinness in women. Psychological Reports, 47, 483-491.

4. Cash, T. F., & Pruzinsky, T. (1990). Body images: development, deviance, and

change. New York: NY, Guilford Press.

5. Cash, T. F., & Brown, T. A. (1987). Body image in anorexia nervosa and bulimia

nervosa: A review of the literature. Behavioral Modification, 11, 487-521.

6. Fallon, A. E. & Rozin, P. (1985). Sex differences in perceptions of desirable body

shape. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 94, 102-105.

7. Garner, D. M. & Garfinkel, P. E. (1979). The Eating Attitudes Test: An index of

the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 9, 273-279.

8. National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (2003). Fact sheet,

http://www.ncsacw.samhsa.gov/files/

9. Sundgot-Borgen, J. (1993). Prevalence of eating disorders in elite female athletes.

International Journal of Sport Nutrition, 3, 29–40.

10. Tiggemann, M., and Slater, A. (2001). A test of objectivity theory in former

dancers and non-dancers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 1, 57-64.

11. Pierce, E. F., & Daleng, M. L. (1998). Distortion of body image among elite

female dancers. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 87, 3, 769-770.

12. Sowder, K., Hennefer, A., Pemberton, C., & Easterly, D. (2004). Defining

“Sport”. Athletic Management, 16.02, February/March.

13. National Federation of State High School Associations (http://www.nfhs.org/)

14. National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) (http://www.ncaa.org/)

15. Carman, J. (2011). Passing on the Magic. Dance Magazine, 85, 12, 50-54.

16. Radell, S. A., Adame, D.D., & Cole, S.P. (2002). The effect of teaching with

mirrors on body image and locus of control in women college dancers: A pretest-

posttest study. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74, 1, A-3.

17. Schneider, D. J. (1974). Effects of dress on self-presentation. Psychological

Reports, 35, 1, 167-170.

18. Fredrickson, B. L., Roberts, T., Noll, S. M., Quinn, D.M., & Twenge, J.M.

(1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification,

restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 75, 1, 269-284.

19. Price, B. R., & Pettijohn, T. F. (2006). The effect of ballet dance attire on body

and self-perceptions of female dancers. Social Behavior and Personality, 34,

8, 991-998.

20. Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. (1982). The eating

attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological

Medicine, 12, 871 878.

21. Williamson, D. A., Davis, C. J., Goreczny, A. J., & Blouin, D. C. (1989). Body

image disturbances in bulimia nervosa: Influences of actual body size. Journal of

Abnormal Psychology, 98, 97-99.

22. Stunkard, A., Sorensen, T. & Schulsinger, F. (1983). Use of the Danish adoption

register for the study of obesity and thinness. In S. Kety (Ed.), The genetics of

neurological and psychiatric disorders (pp. 115-120). New York: Raven Press.

23. Thompson, J. K. & Altabe, M. N. (1991). Psychometric qualities of the figure

rating scale. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10, 5, 615-619.

24. Smith, D. E., Thompson, J. K., Raczynski, J.M., and Hilner, J. E. (1999). Body

image among men and women in a biracial cohort: The CARDIA study.

International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25, 1, 71–82.

25. Garner, D. M., Garfinkel, P. E., and O’Shaughnessy, M. (1985). The validity of

the distinction between bulimia with and without anorexia nervosa. American

Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 581-587.

26. Flynn, K., & Fitzgibbon, M. (1996). Body images and obesity risk among Black

females: A review of the literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 20, 1, 13-24.

27. Furnham, A., Badmin, N., & Sneade, I. (2002). Body image dissatisfaction:

Gender differences in eating attitudes, self-esteem, and reasons for exercise. The

Journal of Psychology, 136, 6, 581-596.

28. Thompson, K. (1996). Assessing body image disturbance: Measures,

methodology, and implementation. In J.K. Thompson (Ed.), Body image, eating

disorders, and obesity (pp. 49-81). Washington, DC: American Psychological

Association.

29. Jackson, A.S., et al. (1996). Changes in aerobic power of women, ages 20 to 64

years. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 28: 884-891.

30. Jackson, A.S., et al. (1990). Prediction of functional aerobic capacity without

exercise testing. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 22:863-870.

31. Cash, T. F. (1990). Body images: Development, deviance, and change. Cash,

Thomas F. (Ed.); Pruzinsky, Thomas (Ed.); New York, NY, US: Guilford Press,

1990. pp. 51-79.

32. Thompson, J. K., and Smolak, L. (2001). Body Image, Eating Disorders, and

Obesity in Youth: Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment. 2ndEd., Washington,

DC, US: American Psychological Association, 389. pp. 54-55.

33. Candy, C. M. & Fee, V.E. (1998). Underlying Dimensions and Psychometric

Properties of the Eating Behaviors and Body Image Test for Preadolescent Girls.

Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27, 117-127.

34. Collins, M. (1991). Body figure perceptions and preferences among preadolescent

children. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10, 100-108.

35. Tiggemann, M. (1992). Body-size dissatisfaction: Individual differences in age

and gender, and relationship with self-esteem. Personality and Individual

Differences, 13, 39-43.

36. Demarest, J. & Langer, E. (1996). Perception of body shape by underweight,

average, and overweight men and women. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 83, 569-

570.

37. Oliver, W. (2008). Body image in the dance class. Journal of Physical Education,

Recreation & Dance (JOPERD), 79, 5, 18-25.

38. Irving, L. (1990). Mirror images: Effects of the standard of beauty on the self- and

body-esteem of women exhibiting varying levels of bulimic symptoms. Journal of

Social and Clinical Psychology, 9, 230-242.

39. Cash, F. & Henry, E. (1995). Women’s Body Images: The results of a national

survey in the USA. Sex Roles, 33, 19-28.

40. Thompson, K. & Stice, E. (2001). Thin-Ideal Internalization: Mounting Evidence

for a New Risk Factor for Body-Image Disturbance and Eating Pathology.

Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 5, 181-183.