Competitive Balance in Men’s and Women’s Basketball: The Cast of the Missouri Valley Conference

Abstract:

Competitive balance typically fosters fan interest. Since revenue associated with men’s sports is typically greater than with women’s, one might expect to find greater levels of competitive balance in men’s sport than women’s sport. The purpose of this research was to test this hypothesis by comparing the competitive balance in a high revenue intercollegiate sport, basketball, for both men and women over a 10-year period in the Missouri Valley Conference. Three measures of competitive balance were employed. In each case, competitive balance was found to be greater among the men’s teams than the women’s. The findings support the hypothesis that where there is greater revenue potential, there should be greater competitive balance.

Introduction:

One of the important differences between sports organizations and other industrial organizations is the issue of competitive balance. Whereas most industrial enterprises attempt to keep competition to a minimum, a lack of competition in the case of sport teams makes for boring games and ultimately fans lose interest (Depken & Wilson, 2006; El Hodiri & Quirk, 1971; Kesenne, 2006; Quirk & Fort, 1992; Sanderson & Siegfried, 2003). This lack of interest would lead to a loss of revenue, as fewer fans would attend games or listen to or watch media presentations. While fans certainly prefer to see their teams win, they want them to at least have a chance of losing. Economists refer to this as the uncertainty of outcome hypothesis (Leeds & Von Allmen, 2005).

In professional sports some teams, frequently those in large markets, normally receive more revenue than their competitors. Those teams are in a position to sign better players and win more frequently, leading to the problem of competitive imbalance. Efforts to alleviate this problem have included salary caps, luxury taxes, revenue sharing, and reverse order of finish drafts. In intercollegiate athletics, attempts to alleviate competitive imbalance are undertaken by the NCAA through its various rules and regulations (National Collegiate Athletics Association, 2006). Likewise, various intercollegiate athletic conferences do this through budgeting and scheduling requirements and the selection of institutional membership (Rhoads, 2004).

In order to maintain fan interest, competitive balance is important in all sports. From the viewpoint of program administrators, it would appear to be particularly important in sports such as basketball and football, in which there are potentially large sources of revenue involved. Similarly, because revenue is typically so much greater for men’s than for women’s sports, one might expect to find greater efforts being made to bring about competitive balance in men’s sports than in sports for women. This might be singularly true where there was a post-season tournament, thus a need to keep fan interest intense throughout the season to help insure interest for post-season play.

The purpose of this study is to test the hypothesis that one would expect to find more competitive balance in men’s than in women’s basketball. More specifically, the researchers compared the degree of competitive balance in both men’s and women’s basketball in the Missouri Valley Conference (MVC) for the 10-year period 1996-97 through 2005-06. The MVC was selected because it annually holds a post-season tournament, and the authors had access to financial data indicating that there was significantly larger revenue associated with men’s basketball than women’s basketball (Missouri Valley Conference, 2006a). The particular time frame was selected as a period of stable membership within the conference.

The Missouri Valley Conference

Established in 1907 as the Missouri Valley Intercollegiate Athletic Association, the MVC is the oldest collegiate athletic conference west of the Mississippi River and the fourth oldest league in the nation (Markus, 1982). The league has been comprised of 32 member institutions at varying times through its history, and it has seen members win national titles on 25 occasions (Missouri Valley Conference, 2006b).

The MVC now features 10 league members: Bradley University, Creighton University, Drake University, the University of Evansville, Illinois State University (ILSU), Indiana State University (INSU), Missouri State University (MSU), the University of Northern Iowa (UNI), Southern Illinois University (SIU), and Wichita State University (WSU).

While the conference’s membership has changed on several occasions since its founding, the most recent changes occurred in the early and mid 1990s. The MVC and the Gateway Collegiate Athletic Conference merged in 1992 (Benson, 2006; Markus, 1982; Missouri Valley Conference, 2006b; Richardson, 2006). The merger resulted in the addition of UNI to bring total league membership to 10 institutions (Carter, 1991; Richardson, 2006). It also resulted in the establishment of MVC championship programs in women’s sports for the first time in conference history.

In 1994, Evansville joined the conference, giving the conference an all-time high 11 league members (Richardson, 2006). Conference membership dropped back to 10 institutions in 1996, when the University of Tulsa left the MVC to join the Western Athletic Conference (Bailey, 2005; Richardson, 2006)

Measuring Competitive Balance

There are several ways of measuring competitive balance, and there is some debate as to which approach is best. Each method attempts to measure something different. Which is best often depends on what the parties to the debate find most useful for their purposes (Humphreys, 2002). Among the more popular measures are the standard deviations of winning percentages of the various teams in the conference or league, the Hirfindahl-Hirschman Index, and the range of winning percentages.

Winning Percentage Imbalance

One popular measure of competitive balance calculates each team’s winning percentage in the conference in a given season. Since there will, outside of a tie, always be one winner and one loser for each game, the average winning percentage for the conference will be .500.

In order to get some idea of competitive balance, the researchers needed to measure the dispersion of winning percentages around this average. To do this, they measured the standard deviation. This statistic measures the average distance the observations lie from the mean of the observations in the data set.

_________________

σ = √ Σ (WPCT – .500)2

N

The larger the standard deviation, the greater the dispersion of winning percentages around the mean, and thus the less the competitive balance. (If all teams had a winning percentage of .500, there would be a standard deviation of zero, and there would be perfect competitive balance.)

Championship Imbalance

Whereas the standard deviation as a measure of competitive balance provides a good picture of the variation among the winners, it does not indicate whether it is the same teams winning every season or if there is considerable turnover among the winners from one season to the next.

Therefore, another method economists use to measure competitive imbalance is the Hirfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which was originally used to measure concentration among firms within an industry (Leeds & Von Allmen, 2005). Since the standard deviation is used to measure percentage winning imbalance, the HHI is used to measure championship imbalance – how the championship or first place finish is spread amongst the various teams. Using this method, the greater the number of teams that achieve championship status over a specific time period, the greater the competitive balance.

The HHI can be calculated by measuring the number of times that each team wins the championship, squaring that number, adding the numbers together, and dividing by the number of years under consideration. Using this measure, it can be concluded that the lower the HHI, the more competitive balance among the teams.

Range of Winning Percentage Imbalance

As suggested above, the standard deviation of winning percentages explains variation around the mean, but it does not specifically reveal if it is the same teams winning or losing from season to season. Likewise, the HHI provides perspective on the number of teams which win the championship over a period of time, but it does not indicate what is happening to the other teams in the conference. It is possible that a few teams could always finish first, but that the other teams could be moving up or down in the standings from one year to another.

One way of gaining some insight into the movement in the standings of all teams over time is to get the mean percentage wins for each team over a specific period. The closer each team is to .500, the greater the competitive balance over this period. If several teams had a very high winning percentage and others had a very low winning percentage, it would suggest that there was not strong competitive balance over time, but that the same teams were winning and the same teams losing year after year.

Results:

In order to arrive at conclusions concerning competitive balance in the MVC, the researchers employed each of the above measures and compared the results for men’s and women’s basketball over the selected period.

Standard Deviation of Winning Percentages

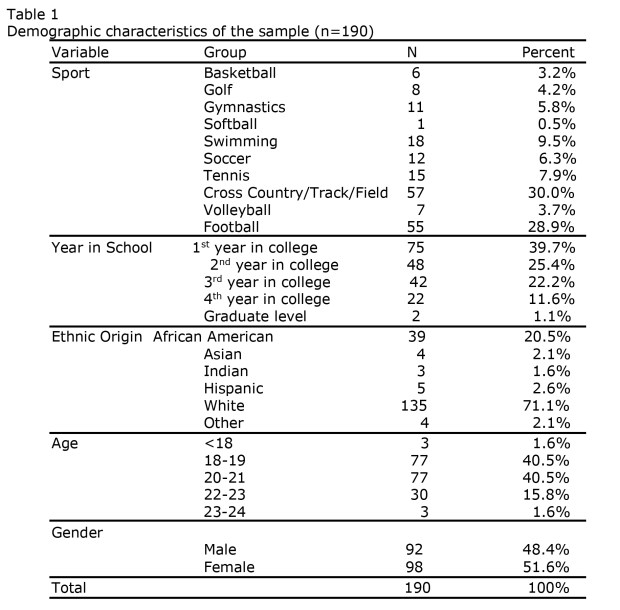

Tables 1 and 2 display the winning percentages for the women’s and men’s basketball teams. Table 3 displays the standard deviations for both the women’s and men’s winning percentages each season. As indicated in Table 3, the men had a mean standard deviation of .2184 compared to a .2404 for the women. This is approximately a 10% difference favoring competitive balance among the men. It can also be noted that the men had a lower standard deviation than the women in seven of the 10 years studied. Likewise, it can be seen that the highest standard deviation for women .2644 (2004-95) exceeded the highest for men, which was .2551 (2002-03). Similarly, the lowest standard deviation for women .2010 (2002-03) was considerably higher than a comparable figure for the men, which was a very low .1527 (1998-99).

Table 1. Winning Percentages- Missouri Valley Conference Women’s Basketball

| Bradley | Creighton | Drake | Evansville | ILSU | INSU | MSU | SIU | UNI | WSU | |

| 1996-97 | 0.5 | 0.389 | 0.778 | 0.111 | 0.722 | 0.5 | 0.722 | 0.5 | 0.278 | 0.5 |

| 1997-98 | 0.222 | 0.611 | 0.944 | 0.056 | 0.5 | 0.556 | 0.778 | 0.389 | 0.444 | 0.5 |

| 1998-99 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.778 | 0.611 | 0.222 | 0.556 | 0.833 | 0.278 | 0.667 | 0.556 |

| 1999-00 | 0.167 | 0.389 | 0.833 | 0.778 | 0.167 | 0.278 | 0.778 | 0.278 | 0.556 | 0.778 |

| 2000-01 | 0.278 | 0.611 | 0.889 | 0.444 | 0.167 | 0.389 | 0.889 | 0.222 | 0.667 | 0.444 |

| 2001-02 | 0.389 | 0.889 | 0.833 | 0.5 | 0.278 | 0.389 | 0.667 | 0.111 | 0.5 | 0.444 |

| 2002-03 | 0.5 | 0.722 | 0.611 | 0.278 | 0.278 | 0.722 | 0.611 | 0.167 | 0.667 | 0.444 |

| 2003-04 | 0.389 | 0.833 | 0.611 | 0.333 | 0.5 | 0.556 | 0.889 | 0.111 | 0.389 | 0.389 |

| 2004-05 | 0.444 | 0.722 | 0.444 | 0.556 | 0.389 | 0.722 | 0.833 | 0.056 | 0.722 | 0.111 |

| 2005-06 | 0.278 | 0.278 | 0.722 | 0.611 | 0.389 | 0.889 | 0.389 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.444 |

| Mean | 0.317 | 0.594 | 0.744 | 0.428 | 0.361 | 0.556 | 0.739 | 0.245 | 0.556 | 0.461 |

Source: Missouri Valley Conference 2005-06 Women’s Basketball Media Guide

Table 2. Winning Percentages- Missouri Valley Conference Men’s Basketball

| Bradley | Creighton | Drake | Evansville | ILSU | INSU | MSU | SIU | UNI | WSU | |

| 1996-97 | 0.667 | 0.556 | 0 | 0.611 | 0.788 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.611 | 0.444 |

| 1997-98 | 0.5 | 0.667 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.888 | 0.556 | 0.611 | 0.444 | 0.222 | 0.611 |

| 1998-99 | 0.611 | 0.611 | 0.278 | 0.722 | 0.389 | 0.556 | 0.611 | 0.556 | 0.333 | 0.333 |

| 1999-00 | 0.556 | 0.611 | 0.222 | 0.5 | 0.278 | 0.788 | 0.722 | 0.667 | 0.389 | 0.278 |

| 2000-01 | 0.667 | 0.788 | 0.444 | 0.5 | 0.667 | 0.556 | 0.444 | 0.556 | 0.167 | 0.222 |

| 2001-02 | 0.278 | 0.788 | 0.5 | 0.222 | 0.667 | 0.222 | 0.611 | 0.788 | 0.444 | 0.5 |

| 2002-03 | 0.444 | 0.833 | 0.278 | 0.444 | 0.278 | 0.111 | 0.667 | 0.888 | 0.389 | 0.667 |

| 2003-04 | 0.389 | 0.667 | 0.389 | 0.278 | 0.222 | 0.278 | 0.5 | 0.944 | 0.667 | 0.667 |

| 2004-05 | 0.333 | 0.611 | 0.389 | 0.278 | 0.444 | 0.278 | 0.556 | 0.833 | 0.611 | 0.667 |

| 2005-06 | 0.611 | 0.667 | 0.278 | 0.278 | 0.222 | 0.222 | 0.667 | 0.667 | 0.611 | 0.778 |

| Mean | 0.506 | 0.68 | 0.278 | 0.433 | 0.484 | 0.39 | 0.606 | 0.668 | 0.444 | 0.517 |

Source: Missouri Valley Conference 2005-06 Men’s Basketball Media Guide

Championship Imbalance

Using the HHI to measure competitive balance for men’s and women’s basketball, the researchers found more competitive balance among the various institutions playing men’s basketball than among their counterparts playing women’s basketball.

Using the HHI for men’s basketball, the researchers found that six teams achieved an outright first place finish (SIU 3, ILSU 2, Evansville 1, Creighton 1, INSU 1, and WSU 1) over the 10-year period studied. In one year, there was a tie for first place (SIU and Creighton in 2001-02). If one point for each outright first place finish and .5 point for each two way tie is given:

HHI= 3.52+22+1.52+12+12+12 = 21.50/10 = 2.150

For women, over the 10-year period only four teams achieved an outright first place finish (Drake 3, MSU 3, Creighton 1, and INSU 1). In 2 years, there was a tie for first place 2000-01 MSU and Drake, and 2002-03 Creighton and INSU). Using the same point distribution as above:

HHI= 3.52+3.52+1.52+1.52 = 29/10= 2.9

In this case, the HHI showed considerably more competitive balance among the men’s basketball teams, than among the women’s. Indeed, the HHI is about 33% higher for the women than for the men. As indicated above this competitive balance advantage for the men can also be seen by the fact that over the 10-year period six different men’s teams achieved a first-place finish, while in the case of the women only four teams finished first.

Range of Winning Percentage Imbalance

If one arbitrarily sets .100 plus or minus the perfect balance, i.e., .500 as a range, which would suggest a high degree of competitive balance over the ten-year period, one once again finds more competitive balance among the men’s teams than among the women’s.

Table 2 suggests that, using this approach, five teams (50%) fit this range. Those teams were Bradley, Evansville, ILSU, UNI, and WSU. Among the others, Creighton, MSU, and SIU seemed to be more consistent winners, while Drake and INSU were at the bottom. But even among the latter, INSU had a winning percentage in 4 of the 10 years. Indeed only one team—Creighton had a winning season each of the ten years. When viewing the range from top to bottom, a variation of .680 (Creighton) to .278 (Drake) a range of .402 is found.

Table 1 indicates that among the women’s teams over this 10-year period a similar five teams fit this range. Those teams were Creighton, Evansville, INSU, NIU, and WSU. Drake and Missouri State were consistent winners, each having only one losing season over the period studied. Meanwhile Bradley, ILSU, and SIU were on the lower end, none of which had an actual winning season over the last 9 years.

While both the men and women had five teams fitting our defined range for a high degree of competitive balance, it should be noted that the range from top to bottom was .499 for the women as compared to .402 for the men. This range is almost 25% greater for women, which again suggests less competitive balance among the women’s teams

Table 3. Standard Deviations of Winning Percentages in Women’s and Men’s Basketball

| Year | Women | Men |

| 1996-97 | 0.2078 | 0.2298 |

| 1997-98 | 0.2538 | 0.2442 |

| 1998-99 | 0.2606 | 0.1527 |

| 1999-00 | 0.2746 | 0.201 |

| 2000-01 | 0.258 | 0.1942 |

| 2001-02 | 0.24 | 0.2142 |

| 2002-03 | 0.201 | 0.2551 |

| 2003-04 | 0.2342 | 0.2313 |

| 2004-05 | 0.2644 | 0.1851 |

| 2005-06 | 0.2095 | 0.2208 |

| Mean | 0.2404 | 0.2184 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data in Tables 1 and 2.

Conclusions:

The uncertainty of outcome hypothesis suggests that a lack of competitive balance among teams in a league or conference can lead to a lack of interest in the games outcome and thus a loss of revenue to teams sponsoring the games. If this were indeed the case, it should follow that the greater the potential revenue possible, the more likely there would be an attempt to bring about competitive balance.

The purpose of this research was to test this hypothesis by comparing the competitive balance in a high revenue intercollegiate sport, basketball, for both men and women over a period of time. Expectations were that, because of the greater revenue associated with men’s basketball, there would be greater competitive balance.

Using the standard deviation of winning percentages, the Hirfindahl-Hirschman Index, and the range of winning percentage imbalance to measure competitive balance, the researchers found in each case that there was greater competitive balance among the men’s basketball teams than for the women’s teams. These findings would support the hypothesis that where there is greater revenue potential, there should be greater competitive balance.

In conclusion, the usual caveats are in order. It is possible that if the researchers analyzed a different time frame within the MVC, or if a different intercollegiate conference was chosen for analysis, a different conclusion may have been reached. It may also be that as women’s basketball continues to grow and generate greater amounts of revenue from ticket sales, media rights fees, and corporate sponsorship, levels of competitive balance may also change. These possibilities provide further research opportunities to test the hypothesis.

References :

Bailey, E. (2005, June 26). Hurricane settled. The Tulsa World, B1.

Benson, J. (2006, October 30). Valley holds Centennial celebration. Knight Ridder Business News. Retrieved April 12, 2007 from http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1170880621&Fmt=3&clientId=328&RQT=309&VName=PQD&cfc=1.

Carter, K. (1991, September 23). Schools jump starting future movement. The Sporting News, 212 (13), 57.

Depken, C.A., & Wilson, D. (2006). The Uncertainty of Outcome Hypothesis in Division I-A College Football. Manuscript submitted for publication.

El Hodiri, M. & Quirk, J. (1971). An economic model of a professional sports league. Journal of Political Economy, 79, 1302-19.

Humpreys, B. (2002). Alternative measures of competitive balance. Journal of Sports Economics, 3, (2), 133-148.

Kesenne, S. (2006). Competitive balance in team sports and the impact of revenue sharing. Journal of Sport Management, 20, 39-51.

Leeds, M. & vonAllmen, P. (2005). The Economics of Sports. Boston: Pearson-Addison Wesley.

Markus, D. (1982, February) The best little conference in the country. Sport. 73, 31.

Missouri Valley Conference. (2006a). Finance committee report. St. Louis: Author.

Missouri Valley Conference. (2006b). This is the Missouri Valley Conference. Retrieved April 27, 2007 from http://www.mvc-sports.com/ViewArticle.dbml?DB_OEM_ID=7600&KEY=&ATCLID=271380.

National Collegiate Athletics Association (2006). 2006-07 NCAA Division I manual. Indianapolis, IN: Author.

Quirk, J. & Fort, R.D. (1992). Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Team Sports. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rhoads, T.A. (2004). Competitive Balance and Conference Realignment in the NCAA. Paper presented at the 74th Annual Meeting of Southern Economic Association, New Orleans, LA.

Richardson, S. (2006). A Century of Sports: Missouri Valley Conference. St. Louis: Missouri Valley Publications.

Sanderson, A.R., & Siegfried, J.J. (2003). Thinking about Competitive Balance. Unpublished manuscript. Vanderbilt University.