Quality Control Procedure for Kinematic Analysis of Elite Seated Shot-Putters During World-Class Events

ABSTRACT

Kinematic analyses of elite shot-put throwers commonly involve shot-trajectory parameters determined under experimental conditions with an accuracy-based procedure. This can be only partially implemented within an event-constrained procedure (as opposed to experimental conditions). Event-constrained procedures, while they provide realistic information collected in an open environment, introduce several constraints that can potentially compromise accuracy measures. This study concerns a quality control procedure intended to address such constraints. The quality control procedure relies on 5 key elements aimed at reducing and reporting error and validating measures of the shot trajectory. The performance of 7 world-class shot-putters during international events was calculated using video data recorded at 50 Hz with a camera located to the side of the athlete. Accuracy was above 75% for all the attempts and above 94% during 4 attempts. This study demonstrated (a) the need to systematically implement this procedure for kinematic analyses based on event-driven recordings; (b) the value of quality indicators in making decisions concerning the instant of release; and (c) the importance of reporting this procedure’s outcomes in terms of error and percentage error.

INTRODUCTION

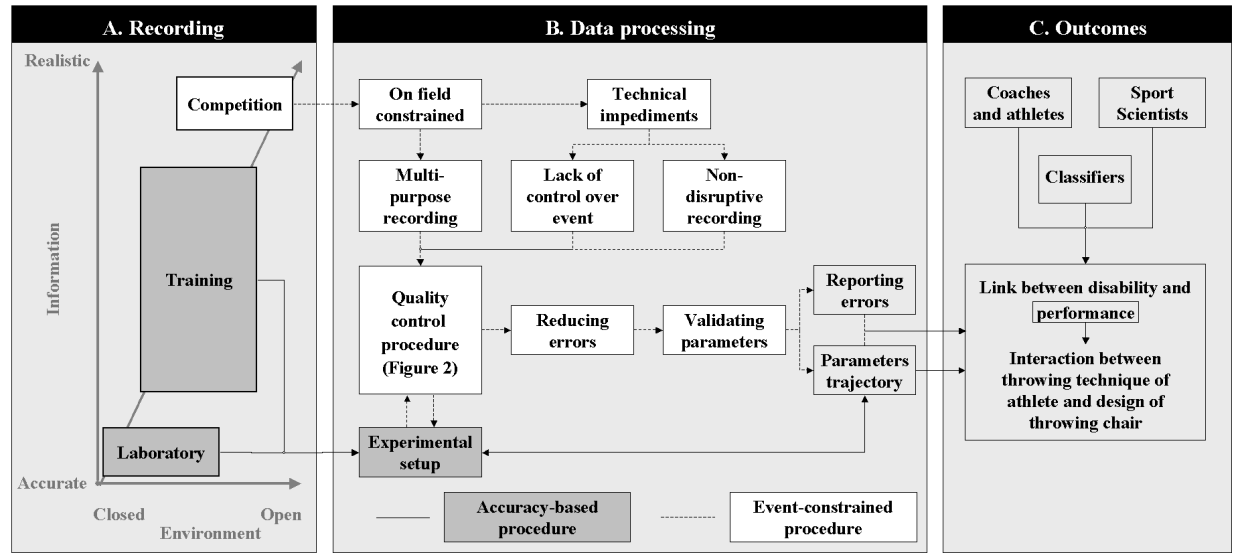

The performance of world elites in the shot put, measured as the distance the shot is thrown, results from the interaction between throwing technique and the design of the throwing chairs (O’Riordan & Frossard, 2006). That interaction shapes the parameters of the shot trajectory, which depends on the position, the velocity, and the angle of the shot at the instant of release ( Ariel, 1979; Dessureault, 1978; Chow, Chae, & Crawford, 2000; Linthome, 2001; Lichtenburg & Wills, 1978; McCoy, Gregor, Whiting, & Rich, 1984; Sušanka & Štepánek, 1988; Tsirakos, Bartlett, & Kollias, 1995; Zatsiorsky, Lanka, & Shalmanov, 1981). Sport scientists, classifiers, coaches, and athletes use the parameters of the shot trajectory to better understand the link between disability and performance (Higgs, Babstock, Buck, Parsons, & Brewer, 1990; McCann, 1993; Vanlandewijck & Chappel, 1996; Williamson, 1997; Chow & Mindock, 1999; Chow et al., 2000; Laveborn, 2000; Tweedy, 2002). Video recording allows for estimation of parameters, using primarily an accuracy-based procedure or event-constrained procedure, as illustrated in Figure 1.

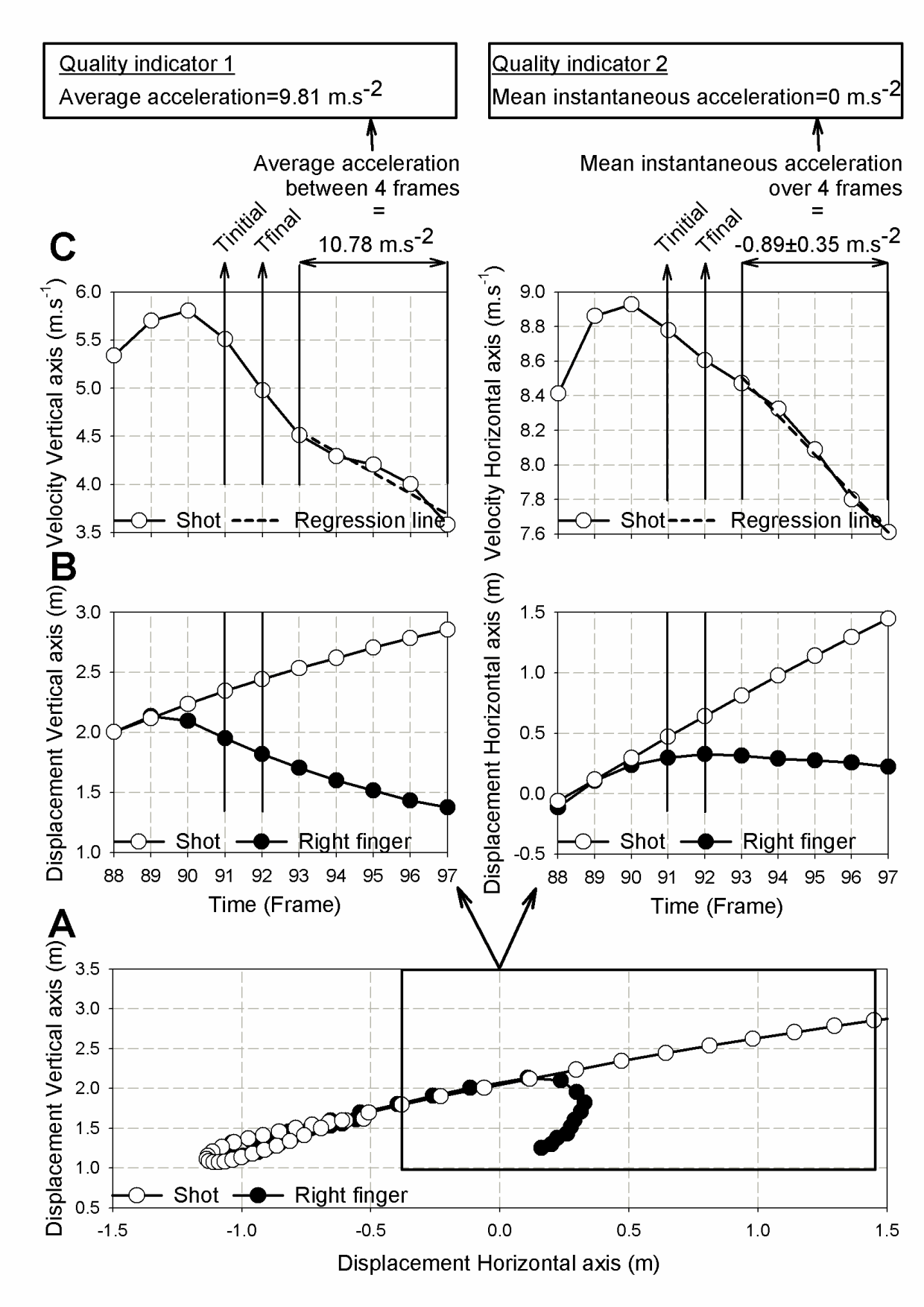

Figure 1. Overview of the video recording (A), the data processing (B) and the outcomes (C) of the parameters of the shot’s trajectory of elite seated shot-putters. The parameters determined using an accuracy-based procedure rely on data collected during training and in laboratory,which presents the advantage of accommodating the typical experimental requirements but it provides only partially realistic information regarding the performance. The event-constrained procedure provides realistic information collected in the open environment presenting several constraints. Thus, a quality control is needed to reduce, validate, and report the errors. This will ensure that sport scientists, classifiers, coaches, and athletes have a better appreciation of the limitations of the data presented about the performance.

Accuracy-based procedure

Video recordings made during training or as part of laboratory motion analysis, whether for routine observation or for research, must accommodate typical experimental requirements for three-dimensional reconstruction, including suitable calibration volume, appropriate number of cameras, precise positioning of cameras, use of active or passive markers, and an unrestricted number of attempts. A flexible set-up of this sort enables an experimental approach employing trial and error, wherein quality control is achieved through repeat recording until the desired kinematic parameters (i.e., shot trajectories) are satisfactorily accurate. The accuracy and validity of parameters reported in research may be taken for granted, even though authors seldom report key indicators like number of frames tracked after release, or calculation of performance using parameters or using tape measure, or the difference between these two performances (Chow & Mindock, 1999; Chow et al., 2000).

Unfortunately, trajectory information obtained from non-competitive environments only partially represents the throwing technique an athlete uses while competing. Participants in a study by Chow et al. (2000) performed, on average, 15±9% below their personal best, leading the researchers to conclude that, in order to develop a data base of ideal performance characteristics, numerous quantitative data needed to be obtained, particularly those collected during leading competitions.

Event-constrained procedure

Video recordings of elite shot-putters’ throwing techniques were made on the field of play during the 2000 Paralympic Games, 2002 International Paralympic Committee World Championships, and select Australian national events (Frossard, O’Riordan, & Goodman, 2005; Frossard, O’Riordan, Goodman, & Smeathers, 2005; Frossard, Schramm, & Goodman, July 2003; O’Riordan, Goodman, & Frossard, 2004). Recording in these open environments entailed certain constraints (Frossard, O’Riordan, Goodman, & Smeathers, 2005; Frossard, Stolp, & Andrews, 2006), presented in Figure 1. Multi-purpose recording becomes necessary for capitalizing on an event’s uniqueness and for securing the distinct kinematic data sets of interest to distinct parties. Classifiers, for instance, may be interested in assessing the full range of upper-body movement (Chow et al., 2000; Tweedy, 2002). Engineers, in turn, may seek to study the deformation of the pole. Coaches’ main interest may be something as specific as hip-movement pathways during forward thrusting, or the exact position of the feet (O’Riordan, Goodman, & Frossard, 2004). Finally, the biomechanist’s interest may well be the parameters of the shot trajectory (Chow et al., 2000). Under experimental conditions, optimal accuracy often results from a focus on one data set at a time, that set obtained using optimal field of view and calibration volume. During competitive events, a compromise must be made as all parameters are observed using a single field of view. Furthermore, various technical barriers are presented on the playing field, including lack of control over the event and inevitable need to make recordings in a non-disruptive fashion. There is, in short, a one-off chance to record any attempt, with space only for one to two cameras, and despite likely obstructions of the field of view by equipment, referees, officials, TV crew, or the like.

Such constraints can be assumed to affect the accuracy of the kinematic data. Even the implementation of an accuracy-based approach within an event-constrained procedure will only partially guarantee sufficient accuracy. Nevertheless, a formal quality control procedure limited to determining shot trajectory parameters and occurring after the video recording stage could offer help to achieve highest possible accuracy.

PURPOSE

The authors’ ultimate aim is to propose a quality control procedure able to reduce error in the measurement of shot trajectory parameters and validate measured parameters, as well as to refine and standardize the format used to report measurement error. The proposed procedure relies on five key quality indicators that should influence decisions about when the moment of release occurs. The paper also has four secondary purposes. First, it comprises a detailed example of the entire procedure as it was deployed with the Class F55 male athlete who won the gold medal at the 2002 International Paralympic Committee (IPC) World Championships. Second, it tracks the procedure’s outcomes in terms of 7 elite shot-putters participating in 2 world-class events. Third, it presents possible sources of error inherent in the proposed videotaping setup. Fourth, it makes several recommendations for future on-field studies.

METHODS

Events

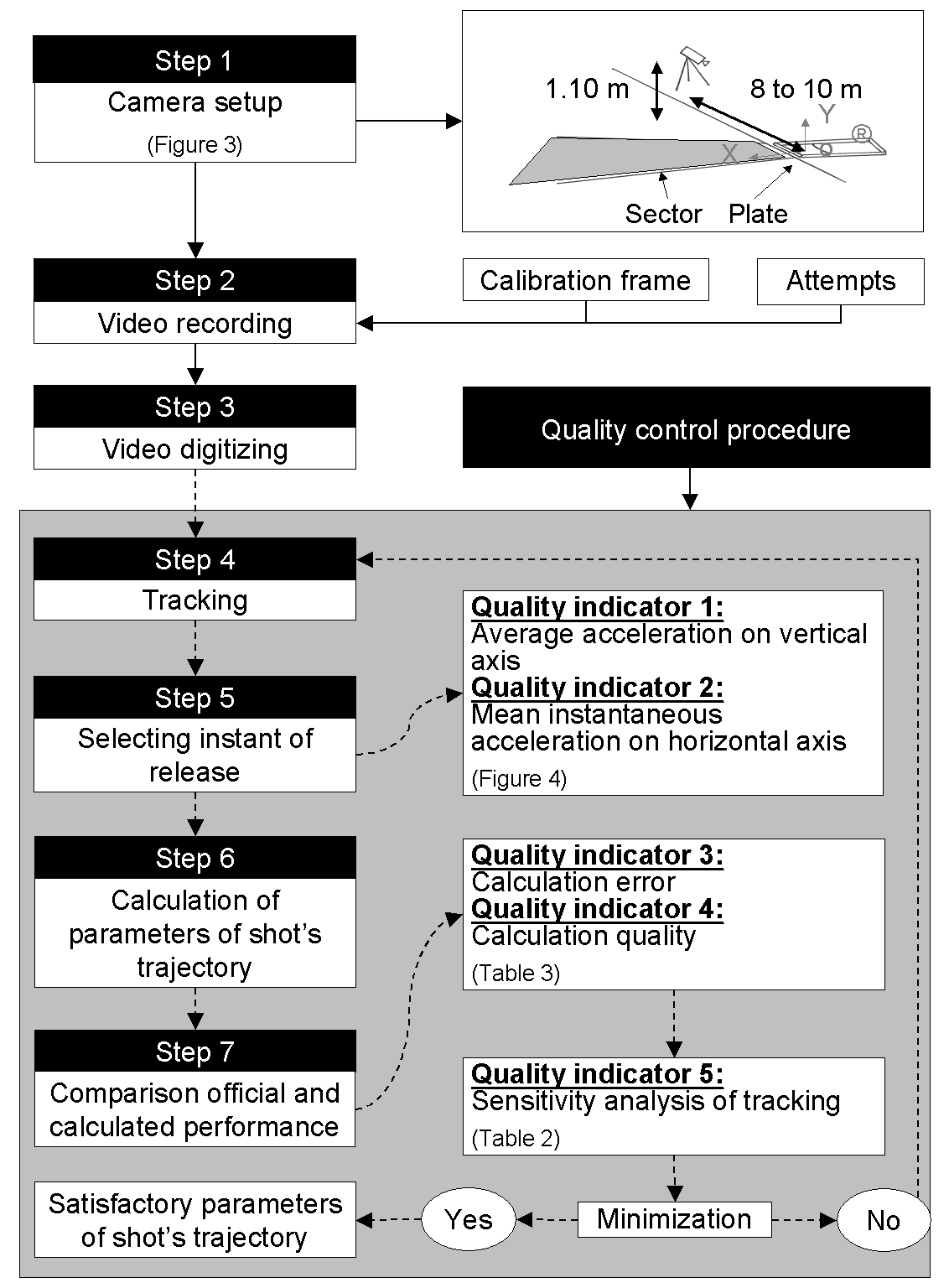

Video recordings were made during two world-class events, the 2000 Paralympic Games held in Sydney, Australia (4 classes of competition), and the 2002 IPC World Championships held in Lille, France (3 classes of competition), as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1

Event and total number of athletes competing in each class included in this study (PG: Sydney 2000 Paralympic Games, WC: Lille 2002 International Paralympic Committee World Championships).

Participants

A total of 51 shot-putters were part of the present study, including 39 males and 12 females. For the competitions, each athlete had been classified according to the latest International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation classification system (Laveborn, 2000). Table 1 illustrates total numbers of these athletes competing in each class, although the present analysis was limited to those who became gold medalists in four select classes (F52, F53, F54, and F55). Though not all-inclusive, the sample was deemed sufficient for illustrating the principles of the quality control procedure. (Gold medalists also typically generate greatest interest among sport scientists, coaches, and athletes.) Female athletes assigned to the F52 and F54 classes had competed jointly at the Sydney Paralympic Games, due to the small numbers of athletes in these classes, and a single gold medal was awarded. For our research, however, the performance of the event’s top competitor in each of these classes was considered. The female Class F53 shot-put event was canceled for lack of athletes.

Data processing

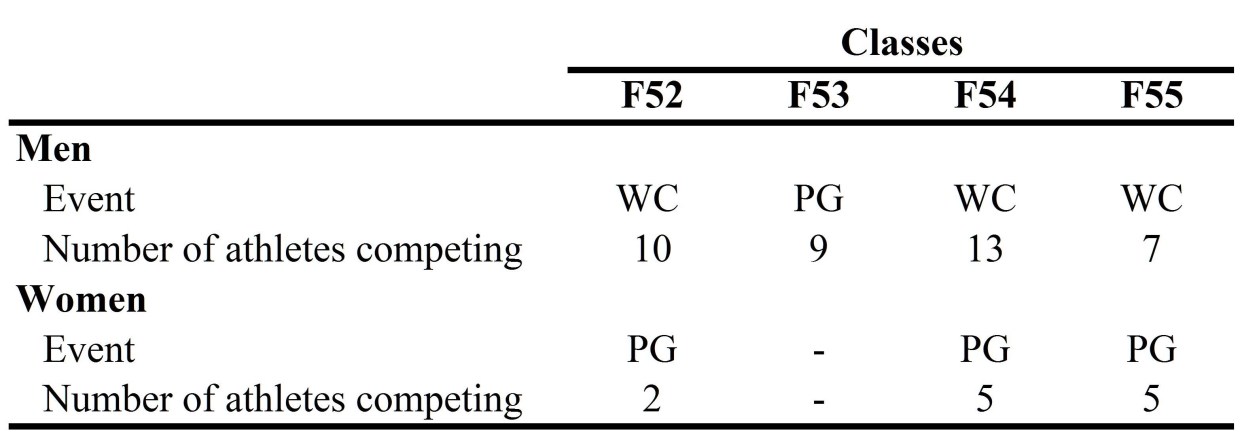

The sequence of the following 7 key steps used to process video data is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Seven key steps of data processing, including the quality control procedure and the five associated quality indicators.

Step 1: Camera set-up

Frossard, Stolp, and Andrews (2003) have previously provided a thorough guide to the practical aspects of video camera set-up during world-class events. Therefore, this paper will limit itself to key elements of that set-up. During the 2 events included in this study, each put was recorded using 1 digital video camera (SONY Digital Handycam DCR-TRV15E), set at a sampling rate of 25 Hz. A “household” camera was chosen because it was affordable, discreet, and readily available. High-resolution cameras, by contrast, require exacting lighting conditions and are expensive and fragile. Some video cameras commercially available at the time of the events would have allowed high-speed filming, but at the cost of compromised resolution.

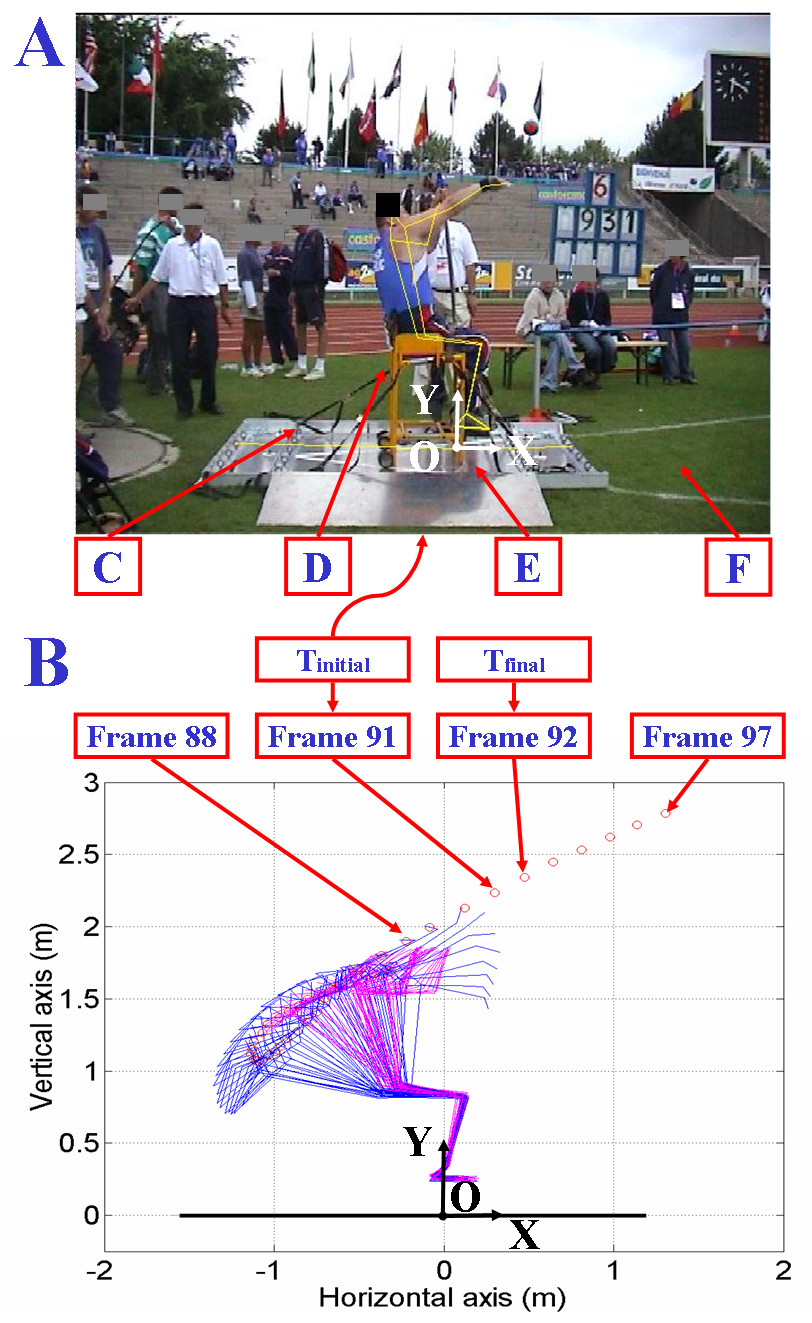

The SONY camera was placed approximately 1.1 m high at a distance between 8.0 m and 10.0 m, perpendicular to the length of the plate. The angle between the optical axis of the camera and the ground was approximately 90 degrees. The field of view included the full length (2.29 m) and full width (1.68 m) of the plate on the ground. The field of view was furthermore enlarged in the direction of the put, to ensure the recording of at least the first 5 frames of the shot’s aerial trajectory (see Figure 3A). Under experimental conditions, this field of view can be obtained by zooming to reduce the perspective error once the camera is positioned with respect to the plate. In this study, the camera was placed relatively close to the plate in an effort to lessen the possibility of intrusion into the field of view by equipment, referees, or TV crews. Nevertheless, the zoom was occasionally used. This camera position resulted in a pixel resolution ranging from 0.95 cm to 1.85 cm, depending on the camera’s position and the zoom setting.

Figure 3.Example of male gold medallist in the class F55 participating in the shot-put event of the 2002 IPC World Championships seated in the throwing frame (D) attached to a plate (E) using ties (C) that is facing the sector (F). Figure A provides an example of field of view of the camera with the body’s segments’ position and the shot at the instant of release (Tfinal – Frame 91). Figure B represents a stick figure of the athlete with the key instants needed to determine the parameters of the shot’s trajectory in the Global Coordinate System (GCS[O, X, Y]).

Step 2: Video recording

A total of 387 attempts, corresponding to nearly every one of the attempts made by each athlete in each class, were recorded and stored on MiniDVs. The duration of the video recording of each attempt was approximately 7 seconds. An attempt began when the referee handed the shot to the athlete and ended shortly after the shot landed on the ground. A customized calibration frame (2 m length x 1.5 m height x 1 m width) containing 43 control points placed on top of the plate was recorded at the beginning and at the end of each event.

Step 3: Video digitizing

The video recording of the calibration frame and of the best attempt in each class (the gold-medal throw) was digitized at 50 Hz using Digitiser 5.0.3.0 software, manufactured by SiliconCOACH Ltd. This sampling rate was achieved by de-interlacing the initial video frames, which affected accuracy only on the horizontal axis.

Step 4: Tracking

The Digitiser software was used to track, frame-by-frame, the center of the shot, the distal end of the middle finger, the position of the wrist, and the origin of the two-dimensional Global Coordinate System (GCS[O, X, Y]). The latter corresponded to the middle of the line of reference located in the front and at the bottom of the throwing frame, used by the referee to measure the performance, as illustrated in Figure 3. The tracking started with the back thrust and ended when the put was no longer within the field of view, which included 5 frames or more after the estimated moment of release. Tracking of the full body was obtained only for the male Class F55 gold medalist (see Figure 3B).

Step 5: Selecting instant of release

The 2 coordinates of the points tracked were imported into a customized Matlab software program (Math Works, Inc.). An operator used the software to select a combination of 2 positions of the shot, allowing calculation of the parameters of the shot’s trajectory (also see Step 6, below). The first position, (Tinitial), corresponding to the instant of release, was indicated by separation between the finger and the shot of a distance larger than the shot’s diameter. The second position, (Tfinal), corresponded to one of the 3 consecutive frames. The two-dimensional coordinates of the displacement were not smoothed or filtered to avoid end point distortions of the limited number of samples after the moment of release.

Step 6: Calculation of parameters of shot trajectory

The Matlab software implemented the classic equations from the literature (Lichtenburg & Wills, 1978; Linthome, 2001) for calculating the trajectory of the shot, allowing the landing distance to be estimated. The performance calculation was determined from the parameters of the shot at the instant of release, including (a) resultant horizontal and vertical components of the translational velocity; (b) resultant horizontal (advancement) and vertical (height) components of the position; and (c) the angle of the trajectory. The performance calculation was also corrected by the radius of the shot, as the official performance was measured from the landing mark on the ground closest to the Global Coordinate System.

Step 7: Comparison of official and measured performance

The performance calculation was compared with the official performance, which was the distance measured by the referee during the event; calculation error indicators and calculation quality indicators were employed as described below. The official performance measure was taken as the value of reference.

Quality control procedure

The quality control procedure relied on two efforts aimed at reducing and reporting error and validating measures of the shot trajectory, as presented in Figure 2. The first included the digitizing of the displacements of the shot and the operator’s subsequent selection of the best combination of Tinitial and Tfinal . Feedback on the quality of the selection was obtained from the 5 key quality indicators, as follows:

Average acceleration after release on vertical axis (Quality Indicator 1—Step 5)

In principle, the vertical velocity of the shot must be constant, and its acceleration must be equal to 9.81 m.s-2. The software therefore calculated the regression line of the vertical velocity between the frame following Tfinal and the last frame available, in order to eliminate random pointing errors. Then, it calculated the average acceleration, as illustrated in Figure 4. The average over four frames was 10.78 m.s-2 in the case of the male in Class F55.

Mean instantaneous acceleration after release on horizontal axis (Quality Indicator 2—Step 5)

In principle, the horizontal velocity of the shot must be constant, and its acceleration must be nil. The software therefore calculated the mean instantaneous acceleration between the frame following Tfinal and the last frame available, as illustrated in Figure 4. The mean over four intervals was -0.89±0.35 m.s-2 in the case of the male in Class F55.

Calculation error (Quality Indicator 3—Step 7)

Expressed in meters and corresponding to the discrepancy between official and calculated performance measures, the calculation error suggests the general quality of the data processing. A positive error indicates a calculated performance measure that overestimates the official performance, while a negative error indicates a calculated performance measure that underestimates it.

Calculation quality (Quality Indicator 4—Step 7)

The calculation quality corresponds to the percentage of the absolute value of the error, in relation to the official performance measure (such as: Calculation quality=[100-(Abs(Error)/Official performance)*100]). This quality indicator provides an understanding of the data processing’s quality in absolute terms, but it cannot indicate the direction of error.

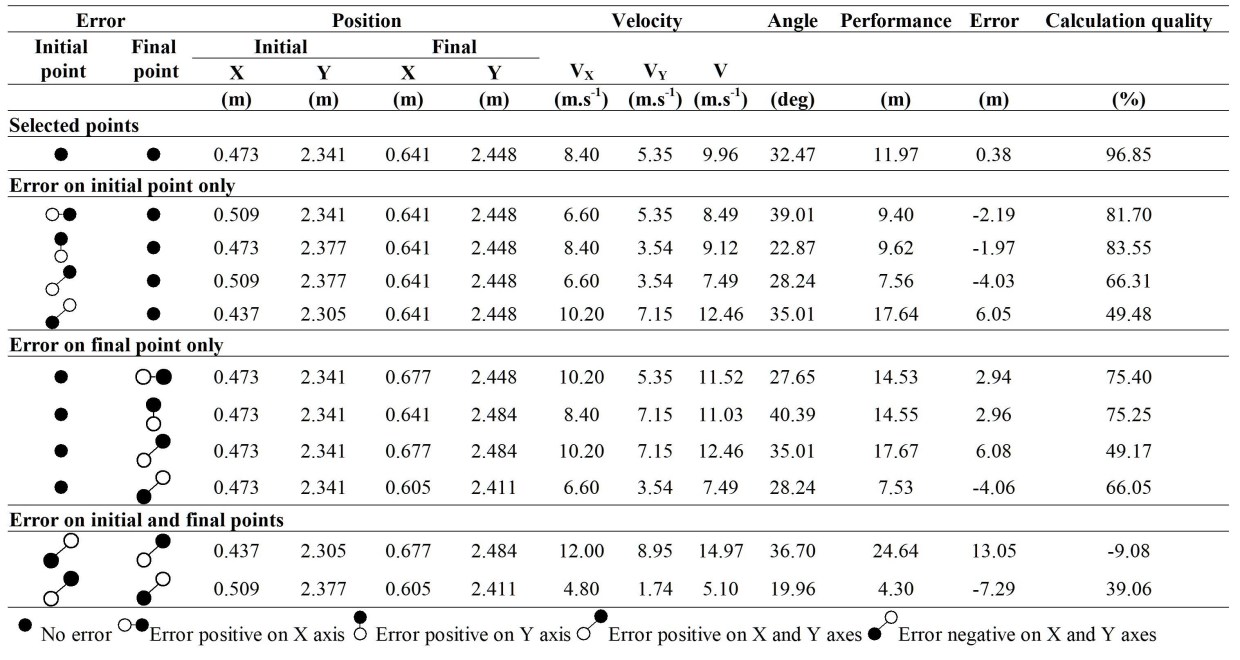

Sensitivity analysis of tracking of Tinitial and Tfinal (Quality Indicator 5—Step 7)

Preliminary studies showed that an error of ±2 pixels could significantly affect calculation of the performance. However, the software was able to provide a succinct sensitivity analysis of the tracking, the outcome of which is reported in Table 2. Sensitivity analysis comprised recalculation of the performance using the combination of positions from Step 6, with 2-pixel positive and negative errors on Tinitial alone, on Tfinal alone, and/or on these two combined. As needed, this feedback guided operator readjustments concerning pointing of the shot (see also Step 4 above).

Table 2

Example of sensitivity analysis of the tracking (Quality Indicator 5) for the male gold medalist in F55 class consisting on recalculating the performance using the combination of positions determined in Step 5 with positive and negative errors of two pixels (3.6 cm) either on Tinitial and Tfinal only or on both combined. The white dot corresponds to the original position; the black dot corresponds to the position with the error. X and Y represent the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively.

Figure 4. Example of feedback provided for the male gold medallist in F55 class to determine the moment of release of the shot (Step 5). Section A represents the vertical position of the shot and the finger during the complete throw until the shot is outside the field of view. The square area corresponds to the zooming on the relevant data to be used to determine the moment of release. Section B presents the selected moment of release (Tinitial = Frame 91), when the separation of the shot and the finger is greater than the diameter of the shot and the second position (Tfinal = Frame 92). Section C provides the velocity of the shot after release as well as the average acceleration (Quality indicator 1) and the mean instantaneous acceleration (Quality indicator 2).

The second of the two efforts to reduce and report error and validate measures of the shot trajectory involved our selection of software that allowed the operator to process the data over an unlimited number of iterations from Step 4 to Step 7, until discrepancies between calculated and official measures had been minimized. Each iteration represented one combination of data points as determined in Step 5.

RESULTS

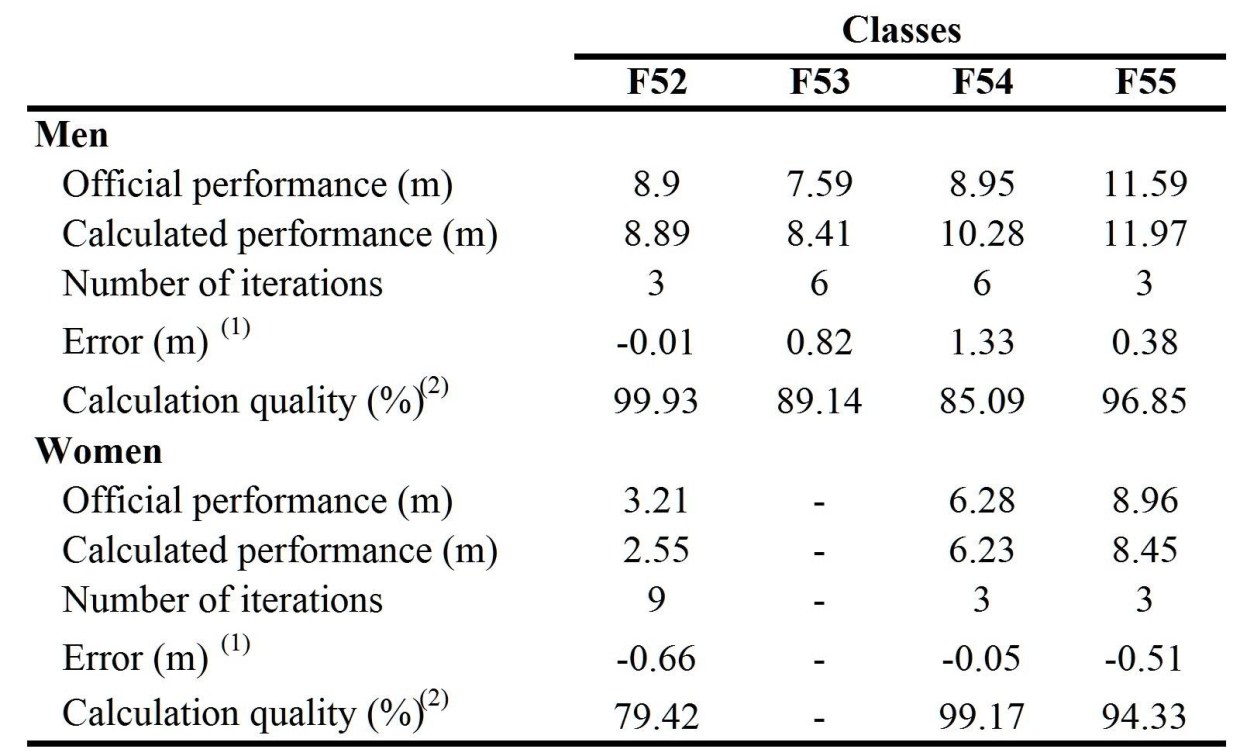

Table 3

Outcome of the quality control procedure. The number of iterations corresponds to the number of attempts made by the operator during the quality control procedure to minimise the difference between the official and calculated performance. The error corresponds to the difference between the official and calculated performance (Quality indicator 3 (1)). The calculation quality corresponds to the percentage of the absolute value of the calculation error in relation to the official performance, such as: Calculation quality=[100-(Abs(Error)/Official performance)*100] (Quality indicator 4 (2)).

Table 3 presents, by competitive class, the quality control procedure’s outcomes, including number of iterations, calculation error, and calculation quality. The smallest difference between a calculated and an official performance measure was obtained from a minimum of 3 (maximum of 9) iterations. Calculation error ranged from 0.01 m to 1.33 m, with a mean of 0.54±0.46 m. The absolute calculation quality ranged from 79% to 100%, with a mean of 92±8 %.

DISCUSSION

These results overall might be considered satisfactory, since athlete performance during 4 out of 7 puts was calculated with accuracy surpassing 94%. However, accuracy surpassed only 79% for three competitive classes (F53 male, F54 male and F52 female), and the number of iterations was high. This finding indicates that, for these puts, the shot trajectory parameters were not determined with sufficient precision, the result primarily of pincushion distortion, sampling frequency, and projection of shot displacements onto the sagittal plane.

Pincushion distortion

Tracking of the shot’s displacement took place at the right top corner of the screen, outside the calibration volume with its maximum 1.5 m on the vertical, 0.5 m on the horizontal, axis. In principle, this zone is the most prone to pincushion distortion, in which straight lines appear to bow in toward the middle. While such distortion must be acknowledged, it is unlikely to have contributed strongly to the lack of accuracy.

Sampling frequency

Despite its sampling frequency of 50 Hz, the shot appears fuzzy at the instant of release because it has traveled significant distances between successive frames. This made it sometimes difficult, during Step 4, to track the exact center of the shot at the instant of release. Sampling frequency could have had impact on the estimation of the position of the shot and on the estimation of the speed of release. However, speed of release and error do not seem to be correlated here. Quality Indicator 5 assisted in determining the most accurate pointing, as illustrated in Table 2.

Projection of the displacements of the shot onto the sagittal plane

In this study, the main source of error was the positioning of the camera to the side of the athlete, which limited calculation of the speed of release to the sagittal plane alone. Visual analysis of the footage, however, showed that the throwing technique of athletes in these classes included more rotation in the transverse plane. The consequent projection of out-of-plane movement onto the sagittal plane tends to result in underestimation of speed of release and overestimation of release angle. This is reflected in our finding of a constant mean instantaneous acceleration after release on horizontal axis (Quality Indicator 2), rather than a nil mean, as was obtained for the Class F55 males. The slope of the curve corresponds, then, to the angle of the shot trajectory in the transverse plane.

In principle, the best way to alleviate these limitations would be to use a three-dimensional motion analysis system with a data acquisition rate ranging up to 100 Hz. Such a system should provide enough samples to accurately determine the shot’s position at the instant of release and to enable further smoothing of the data if required. Furthermore, with such a system the actual trajectory of the shot could be calculated in three, not two, dimensions, which would improve the accuracy of velocity and angular data

Ideally, put-throwing analysis should require at least four cameras, aligned diagonally with each corner of the plate, as well as a preferred fifth camera located above the athlete ( Allard, Stokes, & Blanchi, 1995; Marzan, 1975). Such a camera arrangement, while possible in an experimental framework, would be difficult to implement on the field during a world-class event, its invasive nature perhaps prompting organizing committees to deny researchers access. In addition, some 20 people work in the immediate throwing area alone, making it highly likely that the field of view of cameras on the floor would become obstructed or compromised as the recording of attempts progressed ( Frossard, Schramm, & Goodman, July 2003; Frossard, Stolp, & Andrews, 2003). A more feasible alternative involves using two commercially available high-speed cameras recording at 100 Hz or better, with full resolution. These cameras should be placed, at a distance, to the front and on the side of the thrower, allowing a bi-planar analysis in the sagittal and frontal planes. (Recordings made in this fashion should also accommodate three-dimensional reconstructions.) It would then become possible to estimate the rotation of the throwing upper arm in the transverse plane. Furthermore, the camera in front would provide data allowing one to determine the distance of the shot’s landing position in relation to the sagittal plane. Alternatively, the offset could be obtained from the laser pointer used by officials as they read the 3D coordinates of the shot at the point of landing. The offset could be used to correct for projection onto the sagittal plane.

CONCLUSION

A quality control procedure for video-recording elite male and female shot-putters during world-class events has been developed whose outcome is the calculation, with reasonable accuracy, of performances at outdoor competitive events. The developers of the quality control procedure acknowledge that diminished accuracy results mainly from limited sampling frequency supplied by the selected SONY video camera and from significant out-of-plane movement. The point is made that kinematic analyses of shot-putters at this level would be more beneficial if they were three-dimensional, rather than two-dimensional, even though most throwing action occurs in the sagittal plane. Because use of a three-dimensional motion analysis system is precluded on the field of play for logistical reasons, practical compromises must be made.

The present study made three majors contributions by demonstrating (a) the need to systematically implement a quality control procedure when conducting kinematic analyses of event-constrained recordings; (b) the benefits of using quality indicators to support decisions about tracking and determining instants of release; and (c) the need to report quality control outcomes in terms of both error and calculation quality. Equipped with data of this type, sport scientists, classifiers, coaches, and athletes will have a better feel for the level of accuracy truly obtainable during competitive events. A better appreciation of such data’s limitations should serve them all well. The quality control procedure that has been proposed can be implemented within an accuracy-based effort.

Recommendations from this study would be particularly important to future studies focusing predominantly on from-the-field data. It is further anticipated that this study will provide key information to sport scientists, coaches, and elite shot-put athletes trying to fully grasp the correlation between shot trajectory parameters and either classification or performance.

REFERENCES

Allard, P., Stokes, I. A. F., & Blanchi, J. P. (Eds.) (1995). Three-dimensional analysis of human movement. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ariel, G. (1979). Biomechanical analysis of shotputting. Track and Field Quarterly Review, 79(4), 27–37.

Chow, J. W., Chae, W., & Crawford, M. J. (2000). Kinematic analysis of shot-putting performed by wheelchair athletes of different medical classes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 18, 321–330.

Chow, J. W., & Mindock, L. A. (1999). Discus throwing performances and medical classification of wheelchair athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 99, 1272–1279.

Dessureault, J. (1978). Kinetic and kinematic factors involved in shotputting. Biomechanics 6B, 51–60.

Frossard, L., O’Riordan, A., & Goodman, S. (2005). Applied biomechanics for evidence-based training of Australian elite seated throwers. International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education “Perspectives” series in Press.

Frossard, L., O’Riordan, A., Goodman, S., & Smeathers, J. (2005). Video recording of seated shot-putters during world-class events. 3rd International Days on Sports Science.

Frossard, L. A., Schramm, A., & Goodman, S. (2003, July). Kinematic analysis of Australian elite seated shot-putters during the 2002 IPC World Championships: Parameters of the shot’s trajectory. XIth Congress of the International Society of Biomechanics, Dunedin, International Society of Biomechanics.

Frossard, L. A., Stolp, S., & Andrews, M. (2003). Systematic video recording of seated athletes during shotput event at the Sydney 2000 Paralympic Games. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport .

Frossard, L. A., Stolp, S., & Andrews, M. (2006). Video recording of elite seated shot putters during world-class events. The Sport Journal, 9(3), [pages]. Retrieved from http://www.thesportjournal.org/2006Journal/Vol9-No3/Frossard.asp.

Higgs, C., Babstock, P., Buck, J., Parsons, C., & Brewer, J. (1990). Wheelchair classification for track and field events: A performance approach. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 7, 22–40.

Laveborn, M. (2000). Wheelchair sports: International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation track and field classification handbook. Aylesbury, UK: International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation.

Lichtenburg, D. B., & Wills , J. G. (1978). Maximizing the range of the shot put. American Journal of Physics, 46(5), 546–549.

Linthome, N. (2001). Optimum release angle in the shotput. Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 359–372.

Marzan, G. T. (1975). Rational design for close-range photogrammetry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

McCann, B. C. (1993). The medical disability–specific classification system in sports. Vista ’93 The Outlook: Proceedings of the International Conference on High Performance Sport for Athletes with Disabilities, Edmonton, Rick Hansen Centre.Vanlandewijck and Chappel.

McCoy, R. W., Gregor, R. J., Whiting, W. C., & Rich, R. G. (1984). Technique analysis: Kinematic analysis of elite shot-putters. Track Technique, 2868–2871

O’Riordan, A., & Frossard, L. (2006). Seated shot-put: What’s it all about? Modern Athlete and Coach, 44(2), 2–8.

O’Riordan, A., Goodman, S., & Frossard, L. (2004). Relationship between the parameters describing the feet position and the performance of elite seated discus throwers in Class F33/34 participating in the 2002 IPC World Championships. AAESS Exercise and Sports Science Conference.

Sušanka, P., & Štepánek, J. (1988). Biomechanical analysis of the shot put. Scientific Report on the Second IAAF World Championship. Monarco, IAAF: 1-77.

Tsirakos, D. M., Bartlett, R. M., & Kollias, I. A. (1995). A comparative study of the release and temporal characteristics of shot put. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 28, 227–242.

Tweedy, S. M. (2002). Taxonomic theory and the ICF: Foundation for the Unified Disability Athletics Classification. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 19, 221–237.

Vanlandewijck, Y. C., & Chappel, R. J. (1996). Integration and classification issues in competitive sports for athletes with disabilities. Sport Science Review, 5, 65–88.

Williamson, D. C. (1997). Principles of classification in competitive sport for participants with disabilities: A proposal. Palaestra, 13(2): 44–48.

Zatsiorsky, V. M., Lanka, G. E., & Shalmanov, A. A. (1981). Biomechanical analysis of shotputting technique. Exercise and Sports Science Review, 9, 353–387.