Submitted by: Scott J. Callan, Ph.D. & Janet M. Thomas, Ph.D.

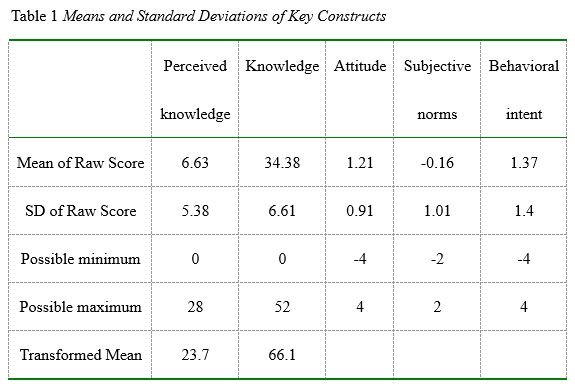

Abstract

In a previous study, it was found that male amateur golfers must possess a variety of shot-making skills to be successful and that relative to driving ability, putting skills and reaching greens in regulation contribute more to explaining tournament success. This present research extends these findings by expanding the investigation to analyze the performance determinants of both female and male amateur golfers. In so doing, we are able to test for the presence of gender-based differences in skill levels and in the relationship between skills and tournament performance. Using a sample of NCAA Division I male and female golfers who participated in tournament play during 2004-2005, our research offers two interesting observations. First, on average, male and female amateur golfers possess different levels of shot-making skills. Second, these disparate skills influence tournament performance differently across genders. Although the causality of these gender-based disparities cannot be identified with certainty, several plausible explanations are considered.

Introduction

In an earlier research study of amateur golfers, we empirically examine the relationship between a male golfer’s tournament performance and a set of shot-making skills (Callan and Thomas, 2004). This initial investigation was the first of its kind to focus on a sample of NCAA Division I male golfers. Statistically, those findings validate analogous research on the performance of professional golfers. What we discovered is that male amateur golfers, like their professional counterparts, must possess a wide variety of shot-making skills to be successful. Moreover, we found that, relative to driving ability, putting skills and reaching greens in regulation contribute more to explaining the variability in a player’s success. This present study extends that research to study both men and women amateur golfers and, in so doing, allows us to test for the presence of gender-based differences in skill levels or in any skill-to-performance relationship.

That gender-specific skill differences exist in the game of golf is explicitly recognized by the United States Golf Association (USGA), which is the governing body for the rules of golf. For example, in its rating system of golf courses, the USGA specifically defines a bogey golfer and a scratch golfer according to the golfer’s gender, as noted below (United States Golf Association, 2005).

Bogey Golfer:

“A male bogey golfer is a player who has a Course Handicap© of approximately 20 on a course of standard difficulty. He can hit tee shots an average of 200 yards and can reach a 370-yard hole in two shots at sea level.

A female bogey golfer is a player who has a Course Handicap© of approximately 24 on a course of standard difficulty. She can hit tee shots an average of 150 yards and can reach a 280-yard hole in two shots at sea level.”

Scratch Golfer:

“A male scratch golfer is a player who can play to a Course Handicap© of zero on any and all rated golf courses. A male scratch golfer, for rating purposes, can hit tee shots an average of 250 yards and can reach a 470-yard hole in two shots at sea level.

A female scratch golfer is a player who can play to a Course Handicap© of zero on any and all rated golf courses. A female scratch golfer, for rating purposes, can hit tee shots an average of 210 yards and can reach a 400-yard hole in two shots at sea level.”

Following these and other gender-specific distinctions made by the USGA, it is reasonable to expect that on average, male golfers are able to drive the ball longer distances off the tee, and female golfers have shorter approach shots to each green. Similar assertions, some with supporting data, are found in the literature, for example, Shmanske (2000) and Wiseman, Chatterjee, Wiseman, and Chatterjee (1994). Such observations motivate the need to learn how such gender-based skill differences translate into scoring performances under actual tournament conditions.

While no existing research papers examine this skill-to-performance relationship across male and female amateur golfers, there are studies that investigate the existence and degree of gender differences among professional golfers. Generally in such investigations, two questions are examined:

- Do the data support the hypothesis that there are statistically different shot-making skills across male and female golfers?

- How do shot-making skills influence a golfer’s tournament performance, and is this set of relationships gender specific?

To illustrate, we offer a few salient examples of this research and an overview of the approach used in each case.

Using performance measures for the 1992 season, Wiseman, Chatterjee, Wiseman, and Chatterjee (1994) investigate the influence of gender differences across golfers in the Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA), Senior PGA (SPGA), and Ladies PGA (LPGA). Overall performance is measured in their study by the average score per round of golf, and the shot-making skills considered are driving distance, driving accuracy, hitting greens in regulation, and putting. What these researchers find is that, on average, male PGA golfers drive the ball farther and hit a larger percentage of greens in regulation than female professionals. Driving accuracy was approximately the same across genders. Because the PGA and LPGA do not collect putting data in the same manner, no gender comparisons could be made about putting ability. However, using multiple regression analysis, Wiseman, et al. (1994) discover that the two most influential skills for female golfers are putting and hitting greens in regulations. These two skills explained 88 percent of the variability in an LPGA member’s average score per round. However, male PGA golfers need a more well-rounded game, as indicated by the importance of all shot-making skills in determining their tournament performance.

In a more recent study, Moy and Liaw (1998) examine golfers’ shot-making skills and tournament performance during the 1993 tournament season for the same professional tours used by Wiseman, et al. (1994). For the most part, Moy and Liaw’s findings agree with those of Wiseman, et al. (1994) regarding PGA golfers’ skills at driving the ball and reaching greens in regulation relative to LPGA golfers. However, they add a variable that captures sand saves, measured as the percentage of time a player gets out of a greenside bunker and scores par or better on the hole. They find that, on average, PGA golfers achieve a higher proportion of sand saves relative to their female counterparts in the LPGA. Given that no comparable putting statistic was available across the two tours, Moy and Liaw were unable to test for gender differences with respect to putting skills.

Shmanske (2000) statistically compares the skill-to-performance relationship for a sample of PGA golfers and LPGA golfers for the 1998 tournament season. In addition to the conventional shot-making skills, Shmanske constructed a comparable putting skill measure for each set of tour professionals. Overall, his results on gender differences are consistent with those of previous researchers. Specifically, he finds that male professional golfers drive the ball farther off the tee, have a higher sand save percentage, and demonstrate a higher putting proficiency. For the other key shot-making skills, namely driving accuracy and hitting greens in regulation, Shmanske observes no meaningful difference across genders.

While these studies have contributed to our understanding of gender differences in professional golf, no analogous investigations have been done for amateur golf. Recognizing the importance of this issue, we extend our previous study of amateur golfers (Callan and Thomas, 2004) to an analysis of skills and performance across male and female amateurs. Using the fundamental framework suggested by Wiseman, et al. (1994) and others, we use a two-pronged approach to our investigation. First, we statistically test for gender-specific skill differences at the amateur level. Second, we use regression analysis to assess the influence of a player’s shot-making skills on tournament performance and statistically determine if these skill-to-performance relationships are affected by gender.

Method

Sample

To conduct our investigation, we use a subset of NCAA Division I male and female golfers who participated in at least one tournament during the 2004–2005 season. Data on members of all Division I teams are not available. The colleges and universities represented in this study are identified in Table 1 along with the number of players on each team, the number of tournaments played during the season, and the average length in yards of the typical course on which the teams played. Most of these data are obtained from Golfstat, Inc. (2005), which is accessible on the Internet at www.golfstat.com.

Notice that the data presented in Table 1 suggest some important distinctions across genders. At a fundamental level, we observe that male golf teams, on average, comprise between 8 and 9 players, while female teams are smaller, averaging between 7 and 8 players. We also note that males play in slightly more tournaments than females, averaging 10.8 for males and 9.7 for females. Consistent with the USGA’s rating system, we also observe that the average male golfer plays courses that are almost 1,000 yards longer than those played by females, specifically 7,042 yards for men versus 6,104 for women. As a consequence, one might infer that male golfers place a higher premium on driving distance, while female golfers might focus more on developing their short game skills.

Measures

For each of the universities included in this research, Golfstat, Inc. collects and reports statistics for player skills and tournament performance. In this study, we use data for the 2004–2005 NCAA Division I tournament season for men and women teams from the same group of institutions. Just as we argue in our 2004 study, AVERAGE SCORE per round is a viable measure of tournament performance, since earnings are not relevant at the amateur level. Moreover, Wiseman et al. (1994) assert that correlation results are actually stronger when scoring average, as opposed to earnings, is used. As for the shot-making skills, we use a set of variables that collectively capture each player’s golf game from tee to green. Among these are measures of driving ability, fairways hit, greens in regulation, sand saves, and putting, which follows the approach used in Callan and Thomas (2004). We briefly discuss each measure in turn, starting with those capturing a player’s long game.

To capture each amateur’s ability to drive the golf ball, we use the variable EAGLES, defined as the cumulative number of recorded eagles (i.e., two strokes under par on any hole) a player makes each season. This variable serves as a proxy for driving distance, which is a statistic not reported by Golfstat. In support of this proxy measure, Dorsel and Rotunda (2001) report a positive correlation between a player’s driving distance and the number of eagles made. Related to driving distance is accuracy in driving the ball into the fairway. To measure this skill, we use the variable FAIRWAYS HIT, measured as the percentage of time a player drives the golf ball off the tee and into the fairway. We also define a variable called GREENS IN REGULATION (GIR) as the percentage of time a player reaches a green in the requisite number of strokes, specifically one for a par three, two for a par four, and three for a par five. This follows the work of Belkin, Gansneder, Pickens, Rotella, and Striegel (1994), who assert that GIR captures a player’s iron skill and success in reaching a green within the regulation number of strokes.

As for a player’s short game, we employ two skill variables that are commonly used in the literature. The first is SAND SAVES, which measures the percentage of time a player gets out of a greenside bunker and achieves a score of par or better. The second is a player’s ability to putt the ball into the hole once on the green. To capture this shot-making skill, we use the variable PUTTS PER ROUND, which measures the average number of putts a golfer makes per round of golf. This follows Belkin, et al. (1994).

Beyond the effect of shot-making skills, we hypothesize that a golfer’s overall performance is influenced by two other key factors – a player’s experience level and any associated team effects. Recognizing experience as a determinant of a golfer’s performance follows Shmanske (1992) and others. In the professional literature, experience is typically captured by the number of years a player has been a professional player. For this analysis of amateur golfers, we construct two experience variables. One is the variable ROUNDS, which is simply the number of tournament rounds completed by each player during the 2004–2005 season. This variable effectively measures a player’s short-term experience, because it captures the way each additional round played in a season adds to the knowledge a player can call upon in subsequent rounds. The second experience measure controls for longer-term cumulative experience and is modeled through a set of dummy variables that reflect the player’s academic age, specifically FRESHMAN, SOPHOMORE, JUNIOR, or SENIOR. The underlying expectation is that the more advanced is a player’s academic age, the more collegiate golfing experience has been gained and, therefore, the lower the expected average score.

The other theorized non-skill determinant of amateur performance is characterized as team effects. These are expected to arise from various factors, including the expertise and experience of the coach and the relative challenge of the courses played by the team. Coaches can directly affect the success of each player in myriad ways, such as through mentoring, leadership, instruction, and guidance. As a leader, the coach is responsible for setting team strategy and for determining the extent of each player’s tournament participation. As an instructor, the coach guides and motivates the development of each player’s athleticism and skills. Hence, collegiate golfers can achieve varying levels of success in the sport based in part on the expertise and experience of their coach, holding skill levels constant.

Likewise, a player’s amateur performance might be affected by the courses played by their team, because course venues, and hence their relative difficulty, vary across collegiate teams. Therefore, a member of a team that plays on relatively easy courses in a tournament season might enjoy a lower average score for that season, and, of course, the converse is true. To account for such team effects, we construct university-specific dummy variables for each player, whereby each identifies the team to which a player belongs.

Procedures

For this study, two conventional statistical procedures were used to analyze the skill and non-skill determinants of amateur golf performance, controlling for gender. One is the two-sample t-test, which was used to statistically examine the difference between mean values of male and female shot-making skills. The second procedure is the use of a multiple regression model that estimates the influence of skill, experience, and team effects on a player’s tournament score, holding constant all other score determinants. Ordinary least squares (OLS) is used to derive the regression estimates.

Results and Discussion

In Table 2, we present descriptive statistics for the sample of 179 amateur golfers, comprising 94 males and 85 females. At the collegiate level, tournaments generally consist of 3 rounds of golf, and each round comprises 18 holes of play. In our sample, the average NCAA Division I male golfer had an average score per round of approximately 75 strokes during the 2004–2005 season. In comparison, the average female golfer had a higher average score per round of about 79 for the season.

Based on the two experience variables, the average male amateur has more experience than the average female. For short-term experience, we observe that males play slightly more than 24 rounds of golf in the season, while females play fewer rounds, at about 22. As for longer-term experience based on academic age, approximately 61 percent of male team members are juniors and seniors, while the comparable value for females is lower at 47 percent.

Turning our attention to shot-making skills, we observe the following distinctions across genders. The average male golfer hits approximately 64 percent of fairways and reaches greens in the regulation number of strokes 60 percent of the time. Female golfers, on the other hand, hit 70 percent of fairways and reach greens in regulation 50 percent of the time. Over the course of a round, a male golfer makes slightly less than 31 putts, while the female golfer makes slightly more than 32 putts. For sand saves, the data show that the amateur male golfer makes par or better when hitting from a bunker 39 percent of the time, which is notably higher than the amateur female golfer, who has a comparable success rate of 29 percent. Lastly, over the course of the 2004–2005 season, the average male player makes 1.8 eagles, while the average female had 0.34 eagles, suggesting superior driving distance for males.

For each variable in the table, we also find the coefficient of variation for each gender group. As a measure of dispersion, this statistic contributes useful information about performance and skills across genders. Notice that for AVERAGE SCORE, the coefficient of variation is smaller for males than females. The same is true for all shot-making skill variables with the single exception of PUTTS PER ROUND. What these results imply is that there is a greater degree of competition among amateur male golfers than among females, an interpretation that follows Moy and Liaw (1998).

By simple observation, these data suggest that there may be statistically significant differences in skill levels across genders. To formally examine this theory, we use two-sample t-tests across the gender-specific skill variables and present our findings in Table 3. Not surprisingly, there are indeed statistically significant differences across genders (i.e., p < 0.0001) for all shot-making skills. Specifically, NCAA Division I male golfers, on average, possess superior shot-making skills relative to their female counterparts for EAGLES, GIR, PUTTS PER ROUND, and SAND SAVES. These findings generally agree with those found in research studies of professional golfers (Wiseman, et al., 1994; Moy and Liaw, 1998; Shmanske, 2000). The opposite relationship holds for FAIRWAYS HIT, the measure of driving accuracy, for which female collegiate golfers are statistically superior to males, on average.

While certainly of interest, the observation of gender-specific skill differences does not ensure that they translate into comparable changes in tournament performances. Investigation of this important issue requires the use of a multiple regression model. To that end, we specify a model to estimate the relationship between an amateur golfer’s average score and each of the determinants identified previously, specifically the set of five shot-making skills, the two experience measures, and the team dummy variables. To identify whether these determinants affect average score differently across males and females, we explicitly control for gender through the use of an interactive binary variable, FEMALE. This variable equals 1 if the golfer is female and 0 if male. It enters the model by itself as well as multiplicatively with each of the other explanatory variables. That way, each score determinant enters the model directly to represent males and multiplicatively with FEMALE to represent any incremental differences for females. In so doing, the estimation results quantify not only how shot-making skills, experience, and team effects influence average score but also whether those effects vary across genders.

The results of this multiple regression analysis are given in Table 4. Based on the adjusted R2 statistic, the regression model explains approximately 95 percent of the variability in a golfer’s tournament performance. Of particular interest are the gender-specific estimates that communicate the relative importance of each shot-making skill on overall performance, holding constant all other skills, team effects, and player experience. We also can assess the influence of all non-skill factors on a player’s average score independent of skill levels, and again, we can do so by gender. The estimated values for male golfers are listed in the first two columns of the table, and the estimates of any incremental differences for females are given in the second pair of columns.

To determine if the gender-based distinctions are collectively relevant, we conducted several F-tests, the results of which are shown at the bottom of Table 4. Other than the test for academic age variables for which gender differences are only marginally significant, all other F-tests indicate that gender differences exist and are statistically significant. These include tests for the overall model, for shot-making skills, and for team effects. These are important findings, which, to the best of our knowledge, have not yet been identified in the literature. They communicate far more than differences in skill levels across males and females. Rather, these results suggest that improvements in skill levels do not translate equivalently to better performance outcomes for both gender groups.

Next consider the individual results for each of the explanatory variables, starting with the set of shot-making skills. With the exception of FAIRWAYS HIT, each shot-making skill has a statistically significant influence on a player’s tournament performance, and each bears the expected algebraic sign. We also find that for several of these shot-making skills, gender differences exist and are statistically significant. Specifically, male golfers gain more tournament success than females from improving SAND SAVES. Conversely, increasing the GIR proportion statistically improves a female golfer’s tournament performance more than it does for a male. An analogous argument is relevant to reducing PUTTS PER ROUND. There are no apparent gender-based differences for EAGLES. Perhaps this outcome is due to the USGA establishing different tee boxes for males and females, which may correctly adjust for any inherent gender-based differences in driving ability.

As for the experience measures, the results suggest that short-term experience measured through ROUNDS does improve tournament performance and does so with no difference between the genders. For cumulative experience, captured through the academic age variables, FRESHMAN, SOPHOMORE, JUNIOR, and SENIOR, only the results for females are reasonable. Specifically, we find that female sophomores achieve higher average scores relative to seniors (the suppressed academic age variable). This makes sense, suggesting that greater collegiate experience improves performance. For males, the parameter on SOPHOMORE is significant, but its algebraic sign is negative. This outcome may be an artifact of the data sample, such as an unusually talented group of male sophomores in the 2004–2005 tournament season. It might also be related to the fact that in this sample, there are about 50 percent more male seniors than male sophomores, while for females there are 12.5 percent fewer seniors than sophomores.

We further find that team effects exist for certain universities. Golfers from East Tennessee State, on average, have higher average scores for the season than those from Vanderbilt University (the suppressed variable), regardless of gender. The same is true for players at the University of Texas. This implies that Vanderbilt University may have a better coaching staff and/or the Vanderbilt teams may play on less challenging courses. Interestingly, the team effect results also suggest a gender difference for teams at Indiana University and Kent State. In both cases, female teams perform at a lower level (i.e., have higher average scores), than their male counterparts, holding constant all other score determinants, including shot-making skills.

To quantify the effect of these differences, we follow Shmanske (2000) and compare the fitted value of average score for an arbitrarily defined male (e.g., a sophomore at Kent State University), with a predicted value that uses female parameter estimates with mean values of male score determinants. What we find is that the fitted value for average score is 73.88, but the predicted value is 75.38. This helps to underscore how the skill-to-performance relationship for females causes their scores to be higher than males, holding all else constant. Using the same approach for an analogously defined female (i.e., a sophomore at Kent State University) yields a fitted value for average score of 79.51, but a predicted value of 77.35, using mean values of female score determinants with male parameter estimates. Again, the difference indicates that the skill-to-performance relationship for males contributes to their scores being lower than that of females, holding skills, experience, and team effects constant.

That these collective results provide some evidence of gender-specific differences in how various factors affect performance is an interesting set of findings. That is, we now have a better sense of why amateur golf performance varies across gender groups. The commonly discussed observation of different average scores for males versus females seems not to be solely a function of differences in skill levels or years of experience but also a function of how changes in score determinants affect golfer performance.

How might we explain these differences? Although definitive answers are beyond the scope of this research, we offer three possible explanations based on selected analyses and theories that have been explored in the literature. These are based on: (1) differences in the degree of competition; (2) varying opportunities within and across university athletic programs; and (3) dissimilar physiological and psychological factors. We present a brief overview of each, which may encourage further investigation of these and other possible explanations.

First, based on the calculations of the coefficient of variation discussed previously and presented in Table 2, there seems to be a greater degree of competition among male amateurs. This is not unlike what Moy and Liaw (1998) find in their analysis comparing professional male and female golfers. More competition among males might encourage longer practice sessions and greater concentration, which in turn should yield higher skill levels and correspondingly greater improvements in performance as those skills develop. Somewhat related to this issue is that male amateurs might also be more highly motivated to practice and may compete more aggressively because of greater earnings potential at the professional level than females. This reality is based in part on higher purses offered on the PGA tour than on the LPGA tour. In fact, some studies of professional golf suggest that golfer success depends on effort, which in turn is influenced by the skewed distribution of tournament purses, meaning that performance improves when the stakes are higher (Ehrenberg and Bognanno, 1990; Shmanske, 2000).

Second, there may be disparate expertise in the coaching staffs and/or significant differences in course difficulty for male teams relative to female teams. This might be the case across institutions or it may arise within a university’s athletic department. The source of such differences is important, since the provision of unequal opportunities based on gender is a violation of Title IX of the Educational Amendment Act of 1972, in which Section 106.41 pertains specifically to athletic programs. Part C of that section identifies several factors that are to be considered when assessing the provision of equal opportunities to both sexes. These include the provision of equipment and supplies, the scheduling of games and practice time, the opportunity to receive coaching and academic tutoring, and the provision of practice and competitive facilities (U.S. Department of Education, 1972).

Third, it is often argued in both the common press and professional journals that gender differences in golf skills and performance might be attributable to physiological or psychological distinctions between males and females. The nature and validity of such arguments are being studied and intensely debated in the literature, and hence no definitive conclusion can be offered here. However, we can identify some of the more salient elements of these arguments, and suggest that they may help to explain the gender differences observed in our sample of amateur golfers.

Some researchers focus on psychological factors that may have differing effects on the play of male and female golfers. To illustrate, consider that Hassmen, Raglin, and Lundqvist (2004) identify a significant correlation between the variability of amateur male golfers’ somatic (or physiological) anxiety levels and the variability of their golf scores. However, Krane and Williams (1992) find no such relationship for their sample of amateur female golfers.

Others ascribe gender-based performance differences to physiological attributes. A common assertion in the professional golf literature is that men’s larger physical size and greater strength explains their ability to drive the ball further than females, and this may in turn explain the lower mean golf scores achieved by males. See, for example, Moy and Liaw (1998). However, others argue that such an assertion is incorrect, because driving a golf ball requires more skill than brute strength alone would provide (Shmanske, 2000). Indeed, in a sophisticated study of the biomechanics of golf, Hume, Keogh and Reid (2005), analyze the two main movements in golf – the swing and the putt, and show that golfers must possess strength, flexibility, and timing to achieve the distance and accuracy necessary for success. Hence, observed gender differences in shot-making skills might be linked to dissimilarities in any or all of these attributes. Some evidence of this hypothesis is offered by Myers, Gebhardt, Crump, and Fleishman (1993), who find within their tests of male and female physical abilities that males scored higher than females on tests of strength and stamina, while females scored higher on tests of flexibility. These findings might explain why male golfers generally drive the ball farther than women and why females typically achieve greater driving accuracy, results found in our analysis and others.

Conclusions

In our previous study of NCAA Division I male golfers, we identified the relationship between an amateur golfer’s tournament performance and various shot-making skills (Callan and Thomas, 2004). This present investigation advances this work by extending the analysis to both females and males. In so doing, we are able to examine whether the skill levels of amateur female golfers differ from those identified for males. Taking this one step further, we also are able to estimate the relationship between each shot-making skill and overall performance for males and females and specifically test for any statistically significant gender differences. To our knowledge, this is the first such study to examine gender differences in amateur golf.

Using a sample of NCAA Division I male and female golfers who participated in tournament play during 2004-2005, our empirical estimation and subsequent analysis supports two important conclusions. First, male and female amateur golfers, on average, possess dissimilar levels of various shot-making skills, and these differences indeed are statistically significant. Such dissimilarities are consistent with the literature examining gender distinctions among professional golfers. In this case, we find that on average, NCAA Division I male golfers possess superior shot-making skills relative to females for all shot-making skills except FAIRWAYS HIT, for which the opposite is true. Second, the manner in which shot-making skills influence tournament performance is not independent of gender. For example, male golfers achieve greater performance improvements by improving SAND SAVES, while females gain more from increasing the GIR proportion and from reducing PUTTS PER ROUND.

Both sets of results are of interest because they improve our understanding of the complexities of amateur golf tournament play. Moreover, through statistical testing, they validate anecdotal evidence of differing skill levels and performance outcomes across male and female collegiate teams. In so doing, the findings suggest the need for further research to learn more about these distinctions and, if necessary, to suggest changes in tournament play that recognize, and perhaps correct for, these disparities.

Although the root causes of gender-based differences in NCAA Division I golf cannot be identified, we do offer several plausible explanations based on research findings from the economics, sports medicine, and physiology literatures. First, we offer the possibility that the higher degree of competition among male golfers may incite more practice and more intensity of play, which in turn may translate into superior skills and/or tournament scores. Second, we suggest that skill and performance distinctions may be related to differences in facilities, coaching, and/or varying course venues. Further study is needed to identify these differences and to determine if there are associated implications for Title IX. Lastly, we consider the role of physiological and psychological factors in explaining gender-specific skill levels and performance in sports, an area that has been, and likely will continue to be, studied in earnest.

We believe that our study and its associated findings are of interest in their own right and contribute to the literature examining both professional and amateur golf. However, it is our hope that this work will have broader implications by encouraging new research in amateur golf and other sports aimed at learning more about the skill-to-performance relationship and the influence of gender and other factors on this important connection in amateur and professional sports.

REFERENCES

- Belkin, D.S., Gansneder, B., Pickens, M., Rotella, R.J., and Striegel, D. (1994) “Predictability and Stability of Professional Golf Association Tour Statistics.” Perceptual and Motor Skills, 78, 1275-1280.

- Callan, Scott J. and Thomas, Janet M. (2004) “Determinants of Success among Amateur Golfers: An Examination of NCAA Division I Male Golfers.” The Sport Journal, 7 (3). Available at http://www.thesportjournal.org/2004Journal/Vol7-No3/CallanThomas.asp.

- Dorsel, T. N. and Rotunda, R. J. (2001) “Low Scores, Top 10 Finishes, and Big Money: An Analysis of Professional Golf Association Tour Statistics and How These Relate to Overall Performance.” Perceptual and Motor Skills, 92, 575-585.

- Ehrenberg, Ronald G. and Bognanno, Michael L. (1990) “Do Tournaments Have Incentive Effects?” Journal of Political Economy, 96, 1307-1324.

- Golfstat, Inc. (2005) “Customized Team Pages-Men and Women,” (accessed August 16, 2005), various teams.

- Hassmen, Peter; Raglin, John S.; and Lundqvist, Carolina (2004) “Intra-Individual Variability in State Anxiety and Self-Confidence in Elite Golfers.” Journal of Sport Behavior, 27 (3), 277-290.

- Hume, Patria A., Keogh, Justin, and Reid, Duncan. (2005) “The Role of Biomechanics in Maximizing Distance and Accuracy of Golf Shots.” Sports Medicine, 35(5), 429-49.

- Krane, Vikki and Williams, Jean. (1992) “Path Analysis Examining Relationships among Cognitive Anxiety, Somatic Anxiety, State Confidence, Performance Expectations, and Golf Performance. “ Journal of Sports Behavior, December, 15(4), 279-96.

- Myers, David C.; Gebhardt, Deborah L.; Crump, Carolyn E.; and Fleishman, Edwin A. (1993) “The Dimensions of Human Physical Performance: Factor Analysis of Strength, Stamina, Flexibility, and Body Composition Measures.” Human Performance, 6 (4), 309-44.

- Moy, R. L. and Liaw, T. (1998) “Determinants of Professional Golf Tournament Earnings.” The American Economist, 42, 65-70.

- Shmanske, Stephen (2000) “Gender, Skill, and Earnings in Professional Golf.” Journal of Sports Economics 1(4), 385-400.

- United States Department of Education. (1972). “Title IX of the Educational Amendment Act.”(Available at http://www.ed.gov/policy/rights/reg/ocr/edlite-34cfr106.html)

- United States Golf Association (USGA) (2005), “Course Rating™ Primer.” (Available at http://www.usga.org/playing/handicaps/course_ratings/course_rating_primer.html, accessed April 25, 2006.)

- Wiseman, F., Chatterjee, S., Wiseman, D., and Chatterjee, N. (1994) “An Analysis of 1992 Performance Statistics for Players on the U.S. PGA, Senior PGA, and LPGA Tours.” In A. J. Cochran and M. R. Farrally (Eds.), Science and Golf: II. Proceedings of the World Scientific Congress of Golf. London: E & FN Spon. 199-204.

TABLE 1

UNIVERSITIES INCLUDED IN THE STUDY |

|

MEN’S GOLF TEAM |

WOMEN’S GOLF TEAM |

| UNIVERSITY |

NUMBER

OF

GOLFERS |

NUMBER OF TOURNAMENTS |

AVERAGE YARDS PER TOURNAMENT (STANDARD DEVIATION |

NUMBER OF GOLFERS |

NUMBER OF TOURNAMENTS |

AVERAGE YARDS PER TOURNAMENT (STANDARD DEVIATION) |

| Coastal Carolina University |

10 |

11 |

6971

(119) |

5 |

10 |

5994

(75) |

| Ea. Tenn. State University |

9 |

10 |

7029

(125) |

7 |

9 |

5978

(106) |

| Fresno State University |

8 |

14 |

6924

(238) |

8 |

11 |

6080

(121) |

Indiana

University |

9 |

11 |

7035

(129) |

8 |

10 |

6120

(111) |

| Kent State University |

8 |

10 |

7017

(156) |

7 |

11 |

6111

(123) |

| University of Kentucky |

7 |

10 |

7091

(227) |

11 |

11 |

6162

(377) |

| University of New Mexico |

8 |

11 |

7128

(330) |

6 |

8 |

6090

(177) |

| University of So. California |

9 |

11 |

6934

(186) |

10 |

9 |

6115

(169) |

| Texas A & M University |

10 |

11 |

7066

(213) |

9 |

10 |

6187

(125) |

University of

Texas |

8 |

10 |

7218

(224) |

8 |

9 |

6169

(186) |

| Vanderbilt University |

8 |

10 |

7045

(215) |

6 |

9 |

6139

(171) |

Average

(std. deviation) |

8.5

(0.93) |

10.8

(1.17) |

7042

(85.34) |

7.7

(1.8) |

9.7

(1.01) |

6104

(66.99) |

Source: Golfstat, Inc. (2005) and individual team Web pages.

TABLE 2

BASIC DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS |

|

MEAN |

STANDARD DEVIATION |

MINIMUM |

MAXIMUM |

COEFFICIENT OF VARIATION |

| VARIABLE |

MALE

(N=94) |

FEMALE

(N=85) |

MALE |

FEMALE |

MALE |

FEMALE |

MALE |

FEMALE |

MALE |

FEMALE |

| Score |

74.97 |

79.23 |

2.22 |

3.53 |

69.95 |

73.50 |

81.33 |

94.45 |

0.030 |

0.045 |

| Eagles |

1.80 |

0.34 |

2.23 |

0.61 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

9.00 |

2.00 |

1.239 |

1.794 |

| Fairways Hit |

0.64 |

0.70 |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.36 |

0.47 |

0.86 |

0.88 |

0.125 |

0.129 |

| Greens in Regulation |

0.60 |

0.50 |

0.08 |

0.10 |

0.33 |

0.16 |

0.81 |

0.65 |

0.133 |

0.200 |

| Putts per Round |

30.83 |

32.31 |

1.42 |

1.29 |

23.00 |

29.84 |

35.33 |

35.71 |

0.046 |

0.040 |

| Sand Saves |

0.39 |

0.29 |

0.15 |

0.13 |

0.00 |

0.06 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

0.385 |

0.448 |

| Rounds |

24.11 |

22.31 |

12.83 |

8.89 |

3.00 |

3.00 |

43.00 |

36.00 |

0.532 |

0.398 |

| Freshman |

0.17 |

0.29 |

0.38 |

0.46 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

2.235 |

1.586 |

| Sophomore |

0.22 |

0.24 |

0.42 |

0.43 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.909 |

1.792 |

| Junior |

0.28 |

0.26 |

0.45 |

0.44 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.607 |

1.692 |

| Senior |

0.33 |

0.21 |

0.47 |

0.41 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

1.424 |

1.952 |

NOTE: Basic statistics for each university dummy variable are available from the authors upon request.

TABLE 3

MEAN DIFFERENCES IN SHOT–MAKING SKILLS ACROSS GENDERS |

| Variable |

Mean Difference

(Male – Female) |

Standard Error* |

t-statistic |

p-value |

| Eagles |

1.4567 |

0.2501 |

5.82 |

<.0001 |

| Fairways Hit |

–0.0540 |

0.0128 |

–4.24 |

<.0001 |

| Greens in Regulation |

0.0982 |

0.0132 |

7.46 |

<.0001 |

| Putts per Round |

–1.4810 |

0.2036 |

–7.27 |

<.0001 |

| Sand Saves |

0.0984 |

0.0216 |

4.56 |

<.0001 |

*Standard error calculation assumes male and female populations have equal variances.

TABLE 4

REGRESSION MODEL PARAMETER ESTIMATES |

| DETERMINANTS |

PARAMETER ESTIMATE |

INTERACTION TERMS (FOR FEMALES) |

PARAMETER ESTIMATE |

| Intercept |

69.40 *** |

Female Intercept |

–15.24 *** |

|

|

|

|

| Shot-Making Skill Variables |

|

Shot-Making Skill Variables |

|

| Eagles |

–0.10 ** |

(Female)(Eagles) |

0.22 |

| Fairways Hit |

0.05 |

(Female)(Fairways Hit) |

–0.40 |

| Greens in Regulation (GIR) |

–21.86 *** |

(Female)(GIR) |

–4.08 * |

| Putts per round |

0.64 *** |

(Female)(Putts per Round) |

0.53 *** |

| Sand Saves |

–1.32 ** |

(Female)(Sand Saves) |

1.68 ** |

|

|

|

|

| Experience Variables |

|

Academic Age Variables |

|

| Rounds |

–0.03 *** |

(Female)(Rounds) |

0.01 |

| Junior |

0.05 |

(female)(Junior) |

–0.23 |

| Sophomore |

–0.41 * |

(Female)(Sophomore) |

0.68 * |

| Freshman |

0.08 |

(Female)(Freshman) |

0.02 |

|

|

|

|

| Team Variables |

|

Team Variables |

|

| Coastal Carolina |

0.44 |

(Female)(Coastal Carolina) |

0.95 |

| East Tennessee State |

1.11 *** |

(Female)(East Tennessee) |

0.49 |

| Fresno State |

0.58 |

(Female)(Fresno State) |

–0.14 |

| Indiana University |

–0.21 |

(Female)(Indiana University) |

1.77 ** |

| Kent State |

–0.34 |

(Female)(Kent State) |

1.13 * |

| Univ. of Kentucky |

0.56 |

(Female)(Univ. of Kentucky) |

0.35 |

| Univ. of New Mexico |

0.32 |

(Female)(Univ. of New Mexico) |

0.07 |

| Univ. of Southern California |

0.44 |

(Female)(Univ. of Southern California) |

–0.55 |

| Texas A&M University |

0.06 |

(Female)(Texas A&M University) |

1.01 |

| University of Texas |

0.99 ** |

(Female)(University of Texas) |

–0.56 |

|

|

|

|

| F-Statistic |

82.75

(p-value< 0.001) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R-Squared |

95.87 |

|

|

| Adjusted R-Squared |

94.71 |

|

|

| F-Statistic (no gender differences overall) |

2.83

(p-value < 0.001) |

|

|

| F-Statistic (no gender differences with respect to shot-making skills) |

2.84

(p-value = 0.012) |

|

|

| F-Statistic (no gender differences with respect to academic age) |

2.10

(p-value = 0.103) |

|

|

| F-Statistic (no gender differences with respect to team variables) |

2.39

(p-value = 0.012) |

|

|

* significant at the 0.10 level, assuming a one-tailed test of hypothesis for skills and two-tailed test elsewhere

** significant at the 0.05 level, assuming a one-tailed test of hypothesis for skills and two-tailed test elsewhere

*** significant at the 0.01 level, assuming a one-tailed test of hypothesis for skills and two-tailed test elsewhere