Intelligence and Football: Testing for Differentials in Collegiate Quarterback Passing Performance and NFL Compensation

Abstract

This article presents an empirical analysis of the relationships between intelligence and both passing performance in college and compensation in the National Football League (NFL). A group of 84 drafted and signed quarterbacks from 1989 to 2004 was selected for the study. The author hypothesizes that intelligence is the most important and perhaps most rewarded at this position, and a wide variety of passing performance statistics are available to separate the effects of intelligence and ability. The OLS-estimated models reveal no statistically significant relationship between intelligence and collegiate passing performance. Likewise, the author finds no evidence of higher compensation in the NFL for players with higher intelligence as measured by the Wonderlic Personnel Test administered at the NFL Scouting Combine.

Introduction

Every February hundreds of collegiate football players gather in Indianapolis at the NFL’s scouting Combine, a four-day event designed for NFL scouts to evaluate the talent of the year’s draft eligible players. Many players likely to be drafted in the first round of the NFL draft will refrain from taking the skills and agility tests in Indianapolis, and will schedule “pro days” at their university where they are more comfortable with the atmosphere and expected results of their workouts. All prospects at the Combine undergo X-rays and physicals to address current and past injuries. All players will also take a 12-minute test designed to measure intelligence, the Wonderlic Personnel Test.

First used by a handful of teams in the 1970s, the Wonderlic is a 50-question test designed to be taken in 12 minutes to measure the athlete’s general intelligence (ESPN, 2002; FairTest Examiner, 1995). The score is calculated as the number of questions correctly answered in the allotted time. As a matter of practice, most players do not answer all 50 questions in the time allotted. Wonderlic scores vary by position, though NFL draftees have averaged a score of 19 over the last 20 years. A Wonderlic score of 20 indicates the test taker has an IQ of 100, which is the average intelligence (Wonderlic.com). The Wonderlic website states that higher scores mean higher intelligence, and intelligence has an impact on playing style and leadership, especially for quarterbacks. The accuracy of this contention will be empirically tested in this article.

This article will also examine the intelligence in two additional models to determine relationship between intelligence and a player’s rookie year compensation and the relationship between intelligence and where an athlete is selected in the NFL draft. This article is particularly relevant in the modern draft era because the millions of dollars spent scouting and signing draftees represent a significant investment by NFL franchises. To the extent that intelligence has an effect on passing ability, NFL franchises may be willing to reward players with such mental abilities. However, if no relationship exists between tested intelligence and performance, then NFL franchises can better utilize resources by focusing on other aspects of player evaluation.

Methodology and Data Sources

The player data for this study were collected from ESPN.com, various NFL draft prospect websites and official university athletics sites. The data include information on 84 drafted NFL quarterbacks who received rookie year salaries between 1989 and 2004. 1 However, due to the limited public availability of Wonderlic scores prior to 1999, most of the quarterbacks used in this study were drafted in the last six years. Although the test results are not officially released, in recent years the Wonderlic scores have been available on the Internet at NFL.com for many players at the Combine. Salary data were obtained from ESPN.com and USAToday.com between 2001 and 2004 and from USA Today newspaper clippings prior to 2001.

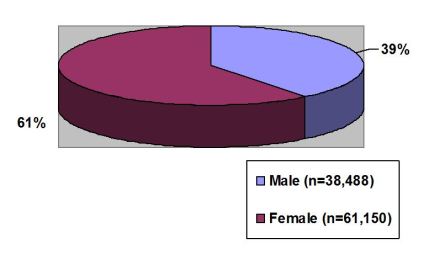

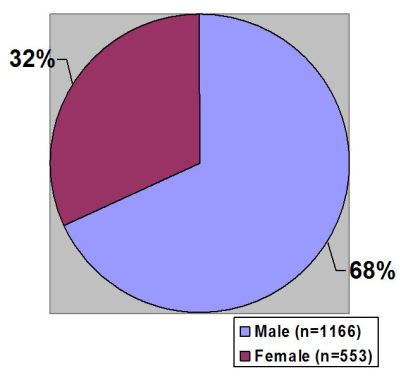

Comparing the distribution of the data used in this study to the total current population of NFL quarterbacks, the author finds a similar proportion of non-white quarterbacks (about 20 percent in each), but a slightly higher proportion of Division 1A quarterbacks in the data (89 percent compared to 80 percent). Such comparisons are important as intelligence tests are frequently found to generate sizable ethnic differences, and such biases could affect the results and interpretation of the model if the sample data is not a representative subset of the true population of NFL quarterbacks (FairTest Examiner, 1995).

Modeling Intelligence and Collegiate Passing Performance

The first relationship this paper addresses is the relationship between intelligence and quarterback passing performance. Using the same set of independent variables in each model, an equation is estimated for each of the dependent variables to measure a quarterback’s passing performance, career passing efficiency (Model I) and total offense per game (Model II). The quarterback’s best collegiate year in terms of total offense per game is used in this analysis.

NFL scouts and coaches assign draft grades to players based on collegiate production and ability. In particular, scouts highly value attributes such as height, quickness, arm strength, vision, leadership and intelligence (CNN/SI, 1998). As such, we develop a model based on the expected contributions of these characteristics (where quantifiable) to a quarterback’s passing performance.

We expect that height may have a positive relationship with passing performance. Taller players can better read defenses, find receivers and avoid having passes deflected by defensive lineman. We expect that a player’s quickness (lower 40-yard dash times) will have a positive relationship with total offense but no effect on passing efficiency. Likewise, NFL scouts expect the quality of a quarterback’s offensive peers to have a positive effect on his passing performance. The models include a DRAFTCLASS variable to control for the general quality of the quarterback’s senior class. DRAFTCLASS is a count variable of players drafted into the NFL during the quarterback’s senior year.

There are no a priori expectations for the relationship between intelligence (as measured by WONDERLIC) and passing performance. Likewise, there are no a priori expectations for the relationship between passing performance and Division 1A football. There are no a priori expectations for the relationship between a quarterback’s race and his passing performance.

The models developed in this section are estimated by OLS without a constant. All dependent and independent variables have been transformed and are centered on the mean of the observed variable to aid in the interpretation of the marginal effects of each explanatory variable. In particular, all effects are for a quarterback with characteristics at the mean, the values of which are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Summary Statistics of Dependent and Independent Variables

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

| HEIGHT (inches) | 74.80 | 1.45 | 71.38 | 77.63 |

| FORTY (seconds) | 4.84 | 0.18 | 4.36 | 5.37 |

| DRAFTCAST (# of drafted offensive teammates) | 3.08 | 2.20 | 0.00 | 7.00 |

| DRAFTCLASS (# of drafted players from team) | 3.69 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 14.00 |

| WONDERLIC | 25.45 | 7.13 | 10.00 | 42.00 |

| Division 1A, 1=yes | 0.89 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Race, 1=non-white | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| NCAA (career NCAA passing efficiency) | 135.91 | 12.09 | 104.35 | 168.82 |

| TOPGB (total offense per game, best year) | 273.57 | 64.94 | 109.36 | 527.20 |

| DRAFT | 108.76 | 82.77 | 1.00 | 250.00 |

| REALSAL | 769,863 | 808,343 | 30,515 | 2,735,854 |

| NFL ROOKIE RATNG | 69.06 | 27.86 | 8.80 | 140.20 |

As shown in Table 2, the hypothesized model for estimating passing performance does a considerably better job explaining TOPGB than NCAA. In fact, the F Value for the Model I is not statistically significant, suggesting that within the sample of players in this dataset, the model has no explanatory power. This may be the case with a relatively homogenous group of individuals – because all players are similar in ability levels, insignificant variation may exist to accurately estimate the model. This is not the case in Model II where significant variation exists within the TOPGB variable, reflecting not only the quality of the team and the opponents, but also the style of offensive attack.

The expected relationship between a player’s HEIGHT and his passing ability is not found in the passing efficiency model (Model I), suggesting that the collegiate passing performances of this group of NFL-caliber quarterbacks do not vary with height. However, RACE is statistically significant in both models, suggesting that non-white quarterbacks are better than their white peers in terms of passing efficiency and total offense per game. In particular, non-white quarterbacks average 8.9 points higher in passing efficiency and 44.8 more total offensive yards per game than their white peers. DRAFTCAST, the quality of the quarterback’s offensive peers, as measured by the number of offensive teammates drafted during his collegiate career, is statistically significant in the total offense per game model. This effect may reflect the self-selection of better quarterbacks into the top collegiate programs known to produce many NFL-caliber prospects. DRAFTCAST is a count variable with a maximum value of seven. The expected negative relationship is found because in the absence of other offense threats, the team will naturally rely more on the abilities of the quarterback. The estimated coefficient has the interpretation that for each NFL-caliber offensive teammate, a quarterback will average 14 fewer total offensive yards per game.

The coefficients in Model I and Model II reveal no statistically significant relationship between a quarterback’s Wonderlic score and his passing performance in college. It should be noted, however, that considerable differences in both terminology and depth exist between collegiate and NFL playbooks, and a quarterback’s intelligence may affect his passing performance in the NFL even if it does not in college. Model V developed in the next section will test if a quarterback’s intelligence affects his NFL passing efficiency during his rookie year.

Table 2: Passing Efficiency and Total Offense models

| (Model I) | (Model II) | |

| NCAA | TOPGB | |

| HEIGHT (inches) | 0.439 | -4.098 |

| (0.44) | (0.84) | |

| FORTY (seconds) | 4.57 | 71.917 |

| (0.52) | (1.68)* | |

| DRAFTCAST (# of drafted offensive teammates) | 0.621 | -14.083 |

| (0.8) | (3.73)*** | |

| DRAFTCLASS (# of drafted players from team) | 0.545 | 0.419 |

| (0.81) | (0.13) | |

| WONDERLIC | 0.043 | 0.366 |

| (0.21) | (0.36) | |

| Division 1A, 1=yes | -1.115 | 4.99 |

| (0.66) | (0.61) | |

| Race, 1=non-white | 8.886 | 44.836 |

| (2.17)** | (2.26)** | |

| Observations | 84 | 84 |

| F Value | 1.37 | 4.58*** |

| R-squared | 0.11 | 0.29 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.03 | 0.23 |

Absolute value of t statistics in parentheses

* significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%

Modeling Intelligence and the NFL draft

This section focuses on the relationship between intelligence and quarterback draft position (Model III) and compensation (Model IV). The player’s rookie year salary (REALSAL) is his first-year compensation in 2004 dollars against the salary cap. Despite the fact that the structuring of contracts varies greatly between first-round picks and all other selections, the player’s rookie year salary reflects the team’s relative willingness to pay for a rookie quarterback given the availability of free agent quarterbacks and the limits of the NFL salary cap and team-specific rookie cap. 2 In recent years, NFL franchises have increasingly used incentive clauses, deferred and option bonuses in addition to traditional signing bonuses to defer the cost of signing first-round draft picks. Such a structuring of contracts also insulates the franchises against the risk inherent in both the evaluation of athlete’s abilities and the likelihood of serious injury. The quarterback’s draft position (DRAFT) is his selection number in the draft (e.g., a quarterback selected with the eighth choice in the second round (40th overall pick) would have a draft position of 40.)

If reality does indeed reflect what the previous models suggest (that intelligence has no affect on passing ability), then it is doubtful that a player’s Wonderlic score will affect the dependent variables – DRAFT and REALSAL – in Model III and Model IV. To the extent that his past performance is indicative of his true ability as a quarterback (and there is great debate on this issue), then the quarterback’s draft position and rookie year salary should primarily be explained by themeasures of his collegiate passing performance and the expected ease of his transition to the professional ranks. The models estimated below reveal that only one of the two measures of collegiate passing performance, TOPGB, is statistically significant in both Models III and IV.

The coefficients of the Models III and IV should be of opposite signs due to the inverse relationship between draft position and a player’s salary. This is indeed observed in the comparison of the two models as shown in Table 3. The signs of the coefficients generally reflect the a priori expectations, with some interesting exceptions. Note that while quarterbacks benefit substantially from the number of collegiate NFL-caliber offensive teammates in Model III and Model IV, Model IV suggest that franchises do make efforts to account for the general quality of the player’s offensive (e.g., offensive cast teammates include wide receivers, running backs, and tight ends, but exclude the offensive line) and defensive teammates as reflected in the negative coefficient of DRAFTCLASS. Both DRAFTCAST and DRAFTCLASS represent competing peer effects in the model. While the estimated DRAFTCAST coefficient is of similar sign and significance in previous literature (Mirabile, 2004), it should be emphasized that the datasets for this and the previous study were considerably different, in particular the latter was composed of both drafted and non-drafted athletes.

Table 3: Draft, Salary, and NFL passing models

| (Model III) | (Model IV) | (Model V) | |

| DRAFT | REALSAL | NFL ROOKIE RATING | |

| HEIGHT (inches) | -14.55 | 216,192 | -4.19 |

| (2.36)** | (3.99)*** | (1.49) | |

| FORTY (seconds) | 200.83 | -2,304,356 | 22.98 |

| (3.68)*** | (4.81)*** | (0.97) | |

| DRAFTCAST (# of drafted offensive teammates) | -12.04 | 128,819 | -2.41 |

| (2.24)** | (2.73)*** | (0.94) | |

| DRAFTCLASS (# of drafted players from team) | 6.15 | -80,140 | -0.50 |

| (1.50) | (2.22)** | (0.28) | |

| WONDERLIC | -1.08 | -1409 | -0.57 |

| (0.85) | -0.13 | (0.96) | |

| Division 1A, 1=yes | -39.30 | 290396 | 8.16 |

| (3.81)*** | (3.20)*** | (1.64) | |

| Race, 1=non-white | -6.47 | -273,860 | -2.89 |

| (0.25) | -1.21 | (0.26) | |

| TOPGB | -0.53 | 5,155 | -0.04 |

| (3.27)*** | (3.63)*** | (0.48) | |

| NCAA | -0.21 | 12,598 | 0.45 |

| (0.27) | (1.84)* | (1.16) | |

| Observations | 84 | 84 | 61 |

| F Value | 7.42*** | 8.85*** | 0.82 |

| R-squared | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.12 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.41 | 0.46 | -0.03 |

Absolute value of t statistics in parentheses

* significant at 10%; ** significant at 5%; *** significant at 1%

The coefficient on the quarterback’s Wonderlic score is not statistically significant, suggesting that NFL franchises do not select smarter quarterbacks sooner or compensate them better than their peers, ceteris paribus. The regression results show that quarterbacks are compensated not only for than their collegiate passing performance, but for how the quarterback is expected to perform in the NFL. Note these expectations take the form of significant coefficients for a player’s height, time in the 40-yard dash, and level of past competition (Division 1A). Such traits are highly prized for rookie quarterbacks, whose ultimate success is determined by their ability to adjust to the size and the speed of NFL opponents. The conclusion from these coefficients is that either intelligence is not an important factor in drafting and compensating rookie quarterbacks or that concerns about a quarterback’s intelligence raise flags which are consistently investigated and subsequently lowered before the draft. Although the models revealed no compensation for smarter players at the quarterback position, such compensation may indeed exist at other positions where such a wide variety of performance statistics are not readily available.

As suggested previously, a quarterback’s intelligence may affect his passing performance in the NFL even if it does not in college. Model V uses the same group of independent variables utilized in previous models to explain the dependent variable, NFL ROOKIE PASSING, the quarterback’s NFL rookie passing efficiency rating. The formula for passing efficiency in the NFL is different from its NCAA counterpart, with NFL passing efficiency employing different scales and a capped system. Because many rookie quarterbacks receive little or no playing time, this variable is not perfectly observed and could be subject to significant measurement error. Only 61 of the 84 observations have observed passing efficiency statistics during their rookie year. In fact, due to the wide variation in playing time among rookie quarterbacks, the variance in this measure is quite large. The results show a negative but not statistically significant relationship between passing efficiency in the NFL and intelligence as measured by the Wonderlic test.

Discrimination in the NFL Draft

In this section, we will briefly address the literature’s history of NFL discrimination and test whether any evidence of discrimination exists at the quarterback position within the developed models. As has been noted in previous literature (Kahn, 1992), white athletes have historically benefited from a race premium. However, using data from the 1996 season, Gius and Johnson (2000) found evidence of reverse discrimination in the NFL with whites earning 10 percent less than their black peers, results they believe were not previously found because prior investigations used data from the 1970s and 1980s.

We can utilize a group means t-test to determine whether the observed distributions of REALSAL and DRAFT are statistically different for white and non-white quarterbacks. After employing t-test of each of these variables, we can reject the hypothesis of equal means for DRAFT but not REALSAL. In particular the mean DRAFT position for white quarterbacks was 117.3 (with a standard error of 10.2) and the mean DRAFT position for non-white quarterbacks was 75 (with a standard error of 17.5). Although this result is significant at the five percent level, given the relatively small sample size, we should be hesitant to infer the existence of discrimination. Model III and Model IV are better able to test for evidence of discrimination against non-white quarterbacks by controlling for all other differences between the two groups. In fact, neither model reveals evidence of such discrimination directly, though this result may change if the time period of the study were different.

Summary and Conclusions

The market for NFL rookie quarterbacks was examined between 1989 and 2004. Attempts to model passing performance using player and team characteristics revealed statistically significant relationships between a quarterback’s collegiate passing performance and his race and teammates. Intelligence, as measured by the Wonderlic score, was statistically insignificant. Likewise, while expected relationships were found between collegiate passing performance and NFL rookie year salary, the author found no statistically significant relationship between intelligence and compensation or intelligence and draft number after controlling for passing ability. Although the models revealed no compensation for smarter players at the quarterback position, such compensation may indeed exist at other positions where such a wide variety of performance statistics are not readily available. Future studies may endeavor to control for more of the franchise- and league-specific factors that impact the drafting and compensation of collegiate athletes.

This article presents empirical evidence that within the modern draft era, there exists no statistically significant relationship between intelligence and quarterback performance at either the collegiate or professional level. Likewise, more intelligent quarterbacks are neither selected earlier nor compensated more for their mental abilities. Since no statistically significant relationship exists between tested intelligence and performance within the data examined in this study, NFL franchises might better utilize resources by focusing on other aspects of quarterback evaluation.

Notes

1. This distinction is made because there are groups of quarterbacks who are drafted but not signed, and likewise a group of undrafted free agent quarterbacks who do sign NFL contracts in their rookie years. The group analyzed in this paper is composed only of players who are both drafted and signed.

2. The rookie cap, the amount of salary cap dollars available to sign rookies, is determined by the number and placement of each team’s draft selections in a given draft.

References

- CNN/SI. (1998) “What NFL teams look for in a player,” CNN/Sports Illustrated. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/football/nfl/events/1998/nfldraft/news/1998/04/14/whatscouts/ (accessed March 7, 2005).

- Duberstein, M.J. (2002) NFL Economics Primer 2002 , National Football League Players Association. http://www.nflpa.org/PDFs/Shared/NFL_Economics_Primer_April_2002.pdf (accessed March 7, 2005).

- Duberstein, M.J. (2003) Pipeline to the Pros , National Football League Players Association. http://www.nflpa.org/PDFs/Shared/Pipeline_To_The_Pros_(Revised_June_2003).pdf (accessed March 7, 2005).

- ESPN. (2002) “So, how do you score?” ESPN.com. http://espn.go.com/page2/s/closer/020228test.html (accessed March 7, 2005).

- FairTest. (1995) “Testing Pro Football Players.” FairTest Examiner. http://www.fairtest.org/examarts/spring95/wonderli.htm(accessed April 5, 2005).

- Gius, M. & Johnson, D. (2000) “Race and Compensation in Professional Football.” Applied Economics Letters, 5, 703-705.

- Kahn, L.M. (1991) “Discrimination in Professional Sports: A Survey of the Literature.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review , 44, 395-418.

- Kahn, L.M. (1992) “The Effects of Race on Professional Football Players’ Compensation.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review , 45, 295-310.

- Mirabile, M. (2004) “The Peer Effect in the NFL Draft.” The Sport Supplement, 12(3). (accessed April 5, 2005).

- USA Today. (2005) “USATODAY.com – Football salaries database.” USAToday.com. http://asp.usatoday.com/sports/football/nfl/salaries/default.aspx (accessed March 7, 2005).

- Whittingham, R. (1992) The Meat Market: The Inside Story of the NFL Draft, New York: MacMillan Publishing Company.

- Wonderlic, Inc. (2004) “How Smart is Your First Round Draft Pick?” Wonderlic.com. http://www.wonderlic.com/news/summer04/mm_article1.htm (accessed December 10, 2004).

Author Information

McDonald P. Mirabile

2747 South Glebe #405

Arlington, VA 22206

919.619.6831