Latest Articles

Watchdogs of the Fourth Estate or Homer Journalists? Newspaper Coverage of Local BCS College Football Programs

Submitted by Edward M. Kian, Ph.D., Stan Ketterer, Ph.D., Cynthia Nichols, Ph.D. and James Poling

ABSTRACT

Sport newspaper departments are regularly mocked for employing hometown journalism deemed too partial in favor of local teams. However, national media are increasingly criticizing affluent, major college football programs for scheduling games against smaller schools from the Football Championship Subdivision, most of which end in lopsided blowouts. Whereas media and sport teams have long formed a symbiotic relationship, major college athletics programs need local media less now due to the ability to post content on their own Web sites. A textual analysis was used to examine hometown media framing of these mismatches by community newspapers that cover football programs in the Big 12 Conference. Results showed newspapers rarely criticized near-by, powerhouse college football teams, but framed FCS teams as inferior. The larger the newspaper examined and the further they were away from the team covered in distance, the more likely they were to criticize hometown coaches and athletic directors. This topic has practical applications for sport mangers who face potential media criticism for scheduling contests against inferior opponents, especially in major college football.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the prevalence and popularity of sports, sports writers have long been denigrated as part of the “toy department” at newspapers due to a perceived lack of objectivity and an unwillingness to engage in critical journalism (Rowe, 2007). A common critique of local sports reporters is they accept gifts from the teams they cover (19). However, the most poignant insults are they engage in “homer” journalism by openly cheering for local squads and becoming too close to athletes. As a result, some reporters fail to fulfill their watchdog roles (2, 16).

In an effort to address questionable industry practices, the Associated Press Sports Editors adopted a code of ethics in 1974, later enhanced in 1991 (21). Sports reporters, however, may be merely acquiescing to the majority of their readers’ desires by providing more coverage of area teams, while generally framing stories about hometown stars more positively.

Further, newspapers usually sell more copies when their local sport teams are successful (50). Coverage of area winning teams could lead to an increase in advertising due to greater readership, which could lead to conflicting interests for newspapers. “Media outlets cover sports with a clear conflict of interest: Their very enterprise is deeply invested in the continued success of commodified sport,” (37, p. 338).

Teams and athletes, in turn, must attribute much of their “staggering popularity” to media coverage that promotes their games and their exploits to readers (McChesney, 1989). Without media coverage, commodified sports struggle to exist. Therefore, sports and media form a “symbiotic economic relationship” (65, p. 38).

Historically, this relationship was strongest with the closest daily newspaper to those college campuses. In many cases, hometown college football reporters are “expected to withhold information that coaches, athletic administrations and athletes perceive as harmful to the program” (43, p. 9). They also occasionally help promote the college’s athletic events that officials believe need more coverage, such as non-revenue sports. In return, reporters may receive access to practices, games, and private contact numbers for coaches and administrators, as well as insider information (43).

However, the need for this symbiotic relationship has diminished for college athletics programs due to huge revenue increases from new television deals with conferences. These deals have increased national exposure for marquee programs in college football (60). Moreover, independent fan websites, such as those affiliated with networks like Rivals.com, have the potential to reach far greater audiences of fans and alumni than local newspapers (26). Finally, more colleges are attempting to disseminate and frame the news on their teams, athletes, and coaches through their official websites and other social media, such as Twitter and Facebook (18, 49).

Meanwhile, the print newspaper industry has suffered setbacks in recent years, highlighted by constant layoffs since the late 1990s, corporate consolidation, decreased circulation, and a loss of advertising revenue (1). Some of the most prominent sports writers have left the newspaper industry to work for online sites (27). In efforts to survive, many newspapers shifted resources to their online sites, while refocusing content on local coverage (59). Whereas circulation figures have declined sharply at nearly every major U.S. newspaper since the late 1990s, most of those publications actually increased their total readership due to traffic on their websites (25). Smaller papers located close to university towns often generate much of their online readership from coverage of college athletics, partly because alumni often move there for professional careers.

However, national media are increasingly criticizing the most famous college athletics programs for many of their practices, particularly the inequities within college sports between the “halves” and “have-nots” (13). During the last two years many national sports journalists have condemned large universities in the National Collegiate Athletics Association for playing smaller ones outside their division. Specifically, they have criticized Football Bowl Subdivision schools that have played games against teams in the Football Championship Subdivision.

The 120 FBS programs in 2012 included all the big-name football programs like Texas, Michigan, Notre Dame, and Louisiana State. Forbes magazine calculated each of those football programs generated at least $100 million in value for their institutions in 2012 (54). In contrast, the 122 FCS schools included Alabama A&M, Monmouth, and Old Dominion. The median 2010 revenue for all FCS athletics programs was just $3 million (48). Therefore, many FCS athletic departments need the guaranteed lump sum payment of generally between $200,000 and $800,000 for playing a road game versus an FBS football team just to stay afloat (61).

But how do hometown newspapers frame such David vs. Goliath mismatches, particularly since the coaches and athletics directors who scheduled those contests provide them access to their programs? Local newspapers risk irritating some of their readers with critical commentary. Moreover, businesses that advertise in these papers may not appreciate negative comments about these games because they want as many visitors as possible on game days, regardless of the opponents. Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory study is to examine how objective hometown newspapers are in framing these college football “paycheck” games.

Historic Connection Between Newspapers And Organizations They Cover

Newspapers have always had a symbiotic relationship with the communities they serve. They provide news and information that residents need for a better understanding of their world, tools for daily living, and entertainment. In return, newspapers depend on local communities for readers and area businesses to help generate advertising revenue.

Journalistic independence is sometimes threatened because of this relationship. Rouner et al. (45) pointed out newspapers are businesses “with profit making taking priority over news reporting,” making it difficult for journalists in most newspapers to remain autonomous of advertising “because large advertisers are a major source of revenue” (p. 106). A survey found nearly 90% of editors at both large and small newspapers reported advertisers had tried to influence the content of stories and what is published (55). More than 70% percent indicated advertisers had attempted to kill stories, and 97% reported they had threatened to withdraw their advertising because of story content, with 90% actually doing so (55). The advertisers were most successful in influencing content of stories at smaller newspapers.

Demers (10) also found editors at larger circulation newspapers had a greater sense of autonomy in decision making than editors at smaller newspapers. Northington (36) suggested editors at smaller newspapers might have more difficulty balancing editorial independence with community involvement. In a study of editors selected to represent the range of newspapers by circulation, Reader (42) found more small-paper editors cited pressure from advertisers attempting to influence content than large-paper editors. But the biggest difference between the types of editors was a perception of direct accountability to the community, which was much stronger at smaller newspapers.

Benefits For Sports Programs Maintaining Public Relations with Local Newspapers

Public relations also plays a role in the symbiotic relationship between sports organizations and newspapers as it helps maintain a tentative but necessary bond. Although some negative stereotypes exist about sports public relations, the value added by maintaining the relationship between sports organizations and local newspapers is essential to fostering the organization’s credibility in local communities, while also lowering its costs for publicity (22). By developing relationships between athletes and journalists, the ability to reach specific groups (i.e., local fans, newspaper subscribers, etc.) is enhanced via free media coverage.

Due to the types of stories that community newspapers can offer to specific publics on a local level, it is logical to develop positive relationships between the various publics involved. Scholars have noted some sports organizations are hesitant to engage in public relations, mainly because they do not understand how to use it properly (23). The assumption exists, however, that regardless of how effectively public relations is used, people will continue to support community sport teams regardless of what transpires (23). But that could change when scandals engulf sport teams or the quality of their performances diminishes over time. Therefore, it is especially important for sport organizations to maintain a positive relationship with local newspapers (52).

Newspaper Framing

Journalists select and organize facts and quotes before embedding them in storylines, a process commonly called framing (11). When writing articles, newspaper reporters emphasize specific points over others through inclusion, exclusion, repetition, and emphasis (44). Media framing helps determine the public’s understanding of issues (28). Moreover, once opinions are formed through framing, they often become more difficult to change (3, 62).

College Football “Paycheck” Games Between FBS and FCS Universities

In1973, NCAA football split into three divisions (I, II, and III), and Division I further divided into three subdivisions in 1978 (9). Division I-A was later re-named the FBS, while Division I-AA is now called FCS (9). FBS schools are allowed to have 85 players on football scholarship, whereas FCS programs can have 63. FBS athletic departments also have higher requirements for the minimum number of men’s and women’s intercollegiate sports they must offer, as well as the annual football home game attendance they must average to remain in the FBS.

Entering the 2012 season, FCS universities defeated ranked FBS teams just three times in 2,252 meetings dating back to the 19th century (34). The most famous was Appalachian State’s 34-32 victory in 2007 at then fifth-ranked Michigan. Whereas two of these upsets occurred since 2007, the average margin of victory by FBS teams was 25.9 points for all inter-division games from 2000 to 2011 (61).

NCAA rules previously limited FBS schools to counting no more than one win against a FCS team every four years toward post-season bowl eligibility. These rules made it counterproductive to play FBS opponents more than once every four seasons. However, due to the advent of 12-game regular-season schedules in 2006, the NCAA now allows one victory against an FCS program to count toward bowl eligibility each season, which has made these mismatches commonplace (61).

Playing a FCS school assures these prominent football programs revenues from an extra home game and adds a probable victory toward bowl eligibility. The often cash-strapped FCS athletics programs use such contests as a recruitment tool for prospective athletes. However, their primary impetus is financial, such as Georgia Southern getting $475,000 to play at Georgia in 2012 (63).

METHODS

Rationale and Research Questions

Although some national media have criticized major college football programs for scheduling FCS opponents, it is unclear how hometown newspapers – who rely heavily on access from the coaches and athletic directors who scheduled these games – frame such mismatches. Therefore, two broad research questions guided this exploratory study:

RQ1: How did hometown newspapers frame FBS-member games vs. FCS opponents?

RQ2: How did hometown newspapers frame the visiting FCS-member programs and their athletes?

Textual Analysis

A textual analysis was conducted of local newspaper stories about Big 12 Conference football programs during the week before and after their 2012 games against FCS opponents. Textual analyses are non-reactive tools that uncover both explicit and subtle underlying meanings within mass media content (33). They are both interpretative and subjective (64).

Sampling Selection

The goal of this project is to examine local newspaper framing of marquee college football programs’ games against teams from the FCS. The Big 12 Conference was selected from the FBS because its schools played the highest percentage (30%) of their non-conference games against FCS teams in 2012 of any conference in the Bowl Championship Series.

Despite its name, the Big 12 Conference had just 10 universities in 2012. Colorado and Nebraska left the Big 12 before the 2011 college football season and were not replaced. Missouri and Texas A&M also left in 2012, but they were replaced by Texas Christian and West Virginia.

Nine of the 10 schools in the Big 12 scheduled a single game against a FCS opponent in 2012, with Texas the exception. The Longhorns had a home game against New Mexico, arguably the worst FBS program. New Mexico was the only FBS team to win one or fewer games in each of the three preceding seasons. In an attempt to study hometown newspaper framing of all Big 12 football programs, Texas’ home date with New Mexico was included in the analysis.

Online versions of stories about these games written by the closest instate newspaper with a daily circulation of at least 30,000 according to the Audit Bureau of Circulations were examined, so long as articles mentioned the FCS opponents. Articles published from the Sunday before each game through the Sunday after each game were included. The story and any accompanying text were examined, including headlines, photo captions, and breakout boxes.

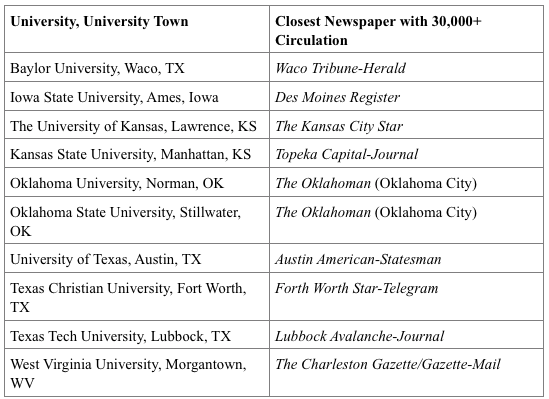

Table 1 shows each university, its location, and its hometown newspaper for this study. Only four of the 10 newspapers were located within the same city as the university: Austin American-Statesman (Texas), Fort Worth Star-Telegram (Texas Christian), Lubbock Avalanche-Journal (Texas Tech), Waco Tribune-Herald (Baylor).

Coding Procedures, Data Analysis, and Trustworthiness

Working independently, three coders each read and wrote notes about how the FCS programs and these games were framed in the 79 stories published in the 10 newspapers. The authors then used the constant comparative method to decipher and define key concepts by unifying their supporting data (17). Specific themes related to how the FCS opponents were framed were given greater importance.

Through its design, this methodology did not aim to reproduce the primary themes from the overall articles. Rather, it sought to uncover the textual constructions related to how the FCS teams and these games were framed within narratives in the FBS schools’ local papers (56). This process is highly interpretive (8). However, our analytical methods were designed to ensure consistent data collection. Moreover, the analysis by multiple researchers (first working independently and then collectively) resulted in a dynamic and layered analytical framework.

RESULTS

Four primary themes emerged from the analysis. Direct passages from newspaper articles will be used to support and contrast these themes.

Successful or Not, These Are FCS Programs!

The most frequent theme was a constant reminder these opponents were from the FCS, and/or they competed in a lower-level division. Moreover, the articles often implied FCS opponents are incapable of competing with FBS schools. For example, The Oklahoman reporter Anthony Slater (53) began his post-game analysis by writing:

Oklahoma beat Florida A&M 69-13 on Saturday night in Norman. The Sooners are now 2-0.

It was over when…

OU scheduled an FCS team. The expected blowout was just that, with OU scoring 14 in the first quarter and never looking back (¶ 1-3).

That same sidebar noted “Florida A&M’s overmatched interior” and a “superior

OU defense,” while concluding that little could be gauged from Oklahoma’s overwhelming victory because “…it was an FCS opponent, so it’s tough to take much” away from such an outclassed opponent (53).

This subtle mockery of the caliber of FCS opponents was paramount in many of the post-game-analyses. For example, in recapping Iowa State’s 37-3 blowout win over Western Illinois, the Des Moines Register wrote, “The Cyclones success Saturday should be tempered by the fact Western Illinois was 2-9 last season and has not beaten an NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision opponent in nine years (31, ¶ 23).

This condescending tone toward FCS programs was also apparent in stories leading up to these games, with the hometown newspapers of FBS programs largely treating these contests as scrimmages. In projecting the effectiveness of the 2012 Kansas State offensive line before its season-opening 51-9 win over Missouri State, an article in the Topeka Capital-Journal surmised, “It’s hard to evaluate offensive-line play in one game – especially against a Division I-AA opponent” (12, ¶ 4).

Even when framing FCS opponents positively, articles still regularly noted these universities compete at a lower level than the FBS programs. For example, Baylor’s hometown paper, the Waco Tribune-Herald, wrote of Sam Houston State: “The Bearkats are a Football Championship Subdivision powerhouse that won 14 straight games before losing to North Dakota State in the national championship game last year, and Baylor knows it can’t take them lightly” (66, ¶ 4).

Further, some of the positive framing of FCS opponents could be viewed as half-hearted compliments, such as the Fort Worth Star-Telegram emphasizing that Grambling State – which Texas Christian defeated, 56-0 – was a superior opponent than fellow FCS member Savannah State, a school pummeled by Oklahoma State, 84-0, a week before. “Don’t hate the dominator either. This wasn’t Savannah State that TCU played. Grambling has a rich football legacy and won eight games a year ago” (29, ¶ 19-20).

However, for most FCS schools – many of which hoped for greater national media exposure from these games– being marginalized was still probably more desirable than being ignored entirely.

FCS Opponents Are Not Worthy of Coverage

This study only analyzed newspaper articles that specifically mentioned FCS opponents. Nevertheless, much content leading up to these games only mentioned the opponent in passing, with very few providing in-depth analyses of the FCS teams or their players. Most stories focused on FCS players who attended high school within the coverage area of the newspaper.

For example, in the only Waco Tribune-Herald article largely focusing on Baylor’s opponent, all four Sam Houston State players mentioned attended high school in the greater Waco area (66). Similarly, an advance of the Kansas-South Dakota State game in The Kansas City Star noted seven South Dakota State players attended high school in the Kansas City area, highlighting the relationship between former teammates at Olathe North High who would square off as opponents in this game (38).

Indicative of the lack of respect for the FCS programs was no player from a FCS school was quoted before these games unless that player was from an area high school. Further, no articles were published with a dateline from the town/city where the FCS university was located, indicating the papers likely never sent any reporter or even hired a freelance writer to interview athletes or coaches from the FCS schools prior to these games. The common narrative for local players from FCS programs was they were honored to play against an FBS school and coming home to do so. For example, a game preview before Iowa State hosted Western Illinois in the Des Moines Register quoted an area resident who suited up for the visitors:

I’ve been watching Iowa and Iowa State play my entire life,” said Nick Eversmeyer, an offensive lineman for the Leathernecks from Wapello. “I actually grew up a pretty big Hawkeye fan. So I’ve always kind of been toward that side. Just to play a team like (Iowa State) will be a pleasure. It’ll pretty much be a dream come true (31, ¶ 10-11).

The Waco Tribune-Herald was the only paper to publish a feature story on an FCS athlete. However, that player – Sam Houston State quarterback Brian Bell – was a graduate of Waco area high school, China Spring, where his father Mark was the head football coach. Moreover, Brian Bell is the younger brother of former Baylor star quarterback Shawn Bell. In other words, those two local ties were prominently mentioned in the feature and seemingly served as the impetus for it (39).

The few post-game articles focusing on FCS teams always tied back to their experiences playing road games against a FBS team. Following a 44-6 rout by hometown program Texas Tech, the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal noted how beneficial this game would be for the loser, Northwestern State. The headline was “Facing Tech will aid Demons down the road.”

Of course, the Big 12 schools easily won all nine games, outscoring the FCS programs by an average score of 51.3 to 9.2. Throw in Texas’ 45-0 win over New Mexico, and the hometown teams outscored their smaller opponents by a combined score of 507 to 83. Nine games were decided by a margin of at least 25 points, with Kansas’ 31-17 win over South Dakota State the lone exception. Therefore, it would have been misleading to frame these contests as competitive afterward.

Scant Criticism of Hometown Teams For Scheduling These Games

Even though these contests resulted in the blowouts projected by many national analysts, largely missing from the hometown newspapers’ coverage were criticisms of the FBS teams for scheduling them. The exception was a series of articles published in The Oklahoman before and after Oklahoma State’s 84-0 annihilation of hapless Savannah State. Jenni Carlson, who already had garnered a reputation for criticizing Oklahoma State, wrote the most critical of these commentaries. It was Carlson’s column about the Cowboys’ quarterback situation in 2007 that resulted in Oklahoma State coach Mike Gundy’s now infamous “I’m a man. I’m 40!” tirade directed at her during a press conference. It is No. 1 on ESPN SportsCenter‘s list of the top 10 all-time most heated exchanges between athletes/coaches and sports media.

In a notes column five days before the game, Carlson (7) included a ranking of Oklahoma State’s all-time “Five Worst Nonconference matchups,” placing the 2012 Savannah State squad atop the list. “The Cowboys will be the first major-college opponent that the Tigers have ever played,” she wrote. “It’s a dubious distinction considering the FCS program hasn’t had a winning season this century” (¶ 6-8).

In an article focusing on the performance of then-Oklahoma State freshman quarterback Wes Lunt, Carlson (4) wrote, “On a night that OSU throttled Savannah State 84-0 and left you wondering if it should be illegal for major-college teams to schedule lower-level teams” (¶ 5). She made her strongest condemnations in a column calling for the end of FBS-FCS matchups: “This madness needs to stop. The NCAA or the BCS or whoever’s in charge of college football these days should ban games against lower-division teams. End the insanity. Bring back the civility” (5, ¶ 5).

No newspaper was close to as negative about these contests as The Oklahoman. Interestingly, The Oklahoman was much less critical of Oklahoma hosting Florida A&M. Carlson (6) wrote that game was only scheduled because Oklahoma had a vacancy on its non-conference schedule after Texas Christian joined the Big 12, “so when OU got desperate, it went looking just about anywhere for an opponent. Its search ultimately landed in Tallahassee with Florida A&M” (¶ 3).

Let’s Let Others Do the Criticizing of These Games, Like Players and Coaches

Whereas reporters from hometown newspapers rarely directly criticized university athletics directors or football coaches for scheduling these matchups, several stories included negative quotes from hometown coaches and players after they were played. Fort Worth Star-Telegram writer Stefan Stevenson (58) quoted TCU Coach Gary Patterson downplaying any significance of his team’s 56-0 win over Grambling State. “They beat an FCS team,” Patterson said of his Frogs. “Simple as that” (¶ 6). Gina Mizell, an OSU beat writer for The Oklahoman, seemingly took advantage of one athlete’s verbal slip-up to form the lead of her game story after Oklahoma State’s 84-0 win over Savannah State: “Joseph Randle immediately caught himself after he said he wished Oklahoma State could have played a ‘real’ opponent in its first game, quickly following with a ‘no comment’ ” (35, ¶ 1).

However, most of these player/coach criticisms were subtle or indirect. For example, in discussing San Houston State outscoring Baylor 20-10 in the first half of an eventual 48-23 Baylor blowout, the Waco Tribune-Herald’s Will Parchman included a quote blaming Baylor’s mental acumen, instead of praising its opponent for its play:

The root of the trouble? Perhaps a pinch of overconfidence.

“We were saying (we’ve got to take them seriously), but the first drive we go out and get a three-and-out, we were like, ‘This is going to be an easy game.’ ” nickelback Ahmad Dixon said (40, ¶ 7-8).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine objectivity of hometown newspapers in framing college football “paycheck” games. Results suggest Big 12 hometown newspapers generally failed to perform their watchdog function by not criticizing the hometown FBS schools for scheduling patsies from the FCS. Others found similar failures of sports journalists to perform this role (e.g., 2, 43). Only The Oklahoman criticized a university, Oklahoma State, before the game for such scheduling, and the newspaper was not located in the same city as the university. But the newspaper did not criticize a university located much closer, Oklahoma, for doing the same thing in a pinch.

Indeed, coverage of FBS programs from smaller newspapers located in the same city as the universities was generally less critical than content published in larger newspapers located further from the college towns. This type of “homer journalism” has long been common in media sports departments (47).

As a result of sports journalists failing to perform their watchdog role, the FBS schools in the Big 12 have little incentive to change such scheduling because they are mainly getting a free ride from these newspapers. These teams nearly always get their extra win over FCS schools to pad their record and enhance their chances for a bowl game. But the readers and fans must endure a boring, lopsided game at high ticket prices, unless the tickets do not sell well and they can get a discount.

The main criticism of these games was indirect and in post-game content, providing further evidence of the local newspapers failing to perform their watchdog role. Moreover, the few critiques mainly appeared in game stories instead of commentaries. Such indirect criticism suggests the sports reporters are heavily concerned about their future access to the teams and/or are concerned with upsetting readers who do not want to read anything negative on the local team.

The hometown papers chiefly framed FCS programs as athletically inferior, particularly through the use of post-game quotes. Tuchman (62) argued reporters use quotes to frame stories as they desire, while claiming they distance themselves from events and people they cover. Even when writing about a historically successful FCS team like Grambling or one that won 14 consecutive games the previous season in Sam Houston State, the hometown FBS newspapers still trivialized FCS successes as coming in a lower division and/or versus lesser competition.

Further, the hometown newspapers in the Big 12 wrote few advances about FCS teams, indicating they felt the other team was unworthy of such coverage. When they did write such stories, they primarily focused on the local angle of players who attended high school in the area. The only advance feature story written about an FCS athlete was about a former local prep star. Thus, readers were largely deprived of in-depth coverage of these teams.

In addition, the lack of datelines from FCS cities indicated the hometown newspapers did not send their reporters there to cover the opposing team. They are apparently unwilling to expend precious resources to do so. Consequently, readers usually received one-sided coverage of the home team.

CONCLUSION

The backlash against scheduling these types of contests by national media is already having effects. In early 2013 athletic directors in the Big Ten agreed to stop scheduling games against FCS opponents (41). Around the same time, Big 12 Conference Commissioner Bob Bowlsby opposed passing legislation to prohibit these games, but said he would discourage his league’s schools from scheduling them. Bowlsby said these games do not make Big 12 teams better and typically resulted in blowouts (24).

Our study showed scheduling of these games was generally not framed negatively by hometown newspapers of the Big 12 schools. Results from this exploratory study, however, cannot be generalized for games with FCS schools beyond Big 12 games during this year. Future research can examine these games over a longer period of time and with hometown newspapers in other conferences.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

It is unknown how the implementation of a four-team college football playoff in 2014 will affect scheduling philosophies of the most powerful programs, such as Big 12 Conference members Oklahoma and Texas. Strength of schedule is supposed to be considered when selecting teams. However, several high-profile coaches, such as Oklahoma’s Bob Stoops, have already expressed skepticism. Stoops pointed out strength of schedule was also supposed to be a key criteria in BCS bowl game selections, but its track record shows win-loss records generally were given more credence, encouraging powerful teams to schedule easy non-conference teams (57).

Future research must examine how FCS teams are framed after major college football implements a playoff system for the first time in its history, starting in 2014. Moreover, scholars can analyze how local and national media frame the powerful and affluent FBS programs that continue to schedule outmatched FCS opponents.

Regardless, hometown media framing was evident in these newspapers, showing that “homer” journalism remains commonplace in at least the smaller- and mid-sized daily newspapers that cover major college football programs in Big 12 conference areas.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

REFERENCES

1. Alterman, E. (2008, March 31). Out of print: The death and life of the American

newspaper. The New Yorker online version. Retrieved from http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2008/03/31/080331fa_fact_alterman

2. Banagan, R. (2011). The decision, a case study: LeBron James, ESPN and

questions about US sports journalism losing its way. Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture & Policy, 140, 157-167.

3. Bronstein, C. (2005). Representing the third wave: Mainstream print media framing of

a new feminist movement. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(4), 783-803.

4. Carlson, J. (2012a, September 1). Oklahoma State football: After blowout, it’s obvious

Wes Lunt is the right guy for the job. The Oklahoman online edition. Retrieved from http://newsok.com/oklahoma-state-football-after-blowout-its-obvious-wes-lunt-is-the-right-guy-for-the-job/article/3706484

5. Carlson, J. (2012b, September 3). Oklahoma State’s 84-point victory should set the

stage for a new scheduling rule. The Oklahoman online edition. Retrieved from http://newsok.com/oklahoma-states-84-point-victory-should-set-the-stage-for-a-new-scheduling-rule/article/3706702

6. Carlson, J. (2012c, August 27). OU chose to play Florida A&M after losing TCU as a

non-conference opponent. The Oklahoman online edition. Retrieved from http://newsok.com/jenni-carlson-ou-chose-to-play-florida-am-after-losing-tcu-as-a-non-conference-opponent/article/3707718

7. Carlson, J. (2012d, August 27). Savannah State coach Steve Davenport talks about

Oklahoma State. The Oklahoman online edition. Retrieved from http://newsok.com/savannah-state-coach-steve-davenport-talks-about-oklahoma-state/article/3704596

8. Creswell, J.W. (2003). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods

approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

9. Crowley, J. (2006). Dividing The House. In the arena: The NCAA’s first century

digital edition. Retrieved from http://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/AB06.pdf

10. Demers, D.P. (1993). Effects of corporate structure on autonomy of top editors at

U.S. dailies. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 70(4), 499-508.

11. Devitt, J. (2002). Framing gender on the campaign trail: Female gubernatorial

candidates and the press. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 79(2), 445-463.

12. Dodd, R. (2012, September 1). KU vs. South Dakota State: Three things to watch.

The Kansas City Star online edition. Retrieved from http://www.kansascity.com/2012/09/01/3791641/ku-vs-south-dakota-state-three.html

13. Doyle, G. (2012, September 7). Pokes, ‘Noles ought to be ashamed of sketchy

scheduling of Savannah State. CBSSports.com. Retrieved from http://www.cbssports.com/collegefootball/story/20088828/pokes-noles-others-ought-to-be-ashamed-of-sketchy-scheduling

14. Duncan, M.C. (2006). Gender warriors in sport: Women and the media. In A.A.

Raney & J. Bryant (Eds.), Handbook of sports and media (pp. 231-252). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

15. Gerbner, G., & Gross, L. (1976). Living with television: The violence profile. Journal

of Communication, 26(2), 172-199.

16. Gisondi, J. (2010). Field guide to covering sports. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

17. Glasser, B.G., & Strauss, F. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for

qualitative research. New York: Aldine De Gruyter.

18. Hambrick, M. (2012). Six degrees of information: Using social network analysis to

explore the spread of information within sport social networks. International Journal of Sport Communication, 5(1), 16-34.

19. Hardin, M. (2005). Survey finds boosterism, freebies remain problems for newspaper

sports departments. Newspaper Research Journal, 26(1), 66-72.

20. Hardin, M., & Shain, S. (2005). Strength in numbers? The experiences and attitudes

of women in sports media careers. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly,

82(4), 804-819.

21. Hardin, M., & Zhong, B. (2010). Sports reporters’ attitudes about ethics vary based

on beat. Newspaper Research Journal, 31(2), 6-19.

22. Hopwood, M.K. (2007). The sports integrated marketing communications mix. In J. Beech & S. Chadwick (Eds.) The Marketing of Sport. London: Prentice Hall.

23. Hopwood, M.K. (2010). Bringing public relations and communication studies to

sport. In M. Hopwood, P. Kitchin, & J. Skinner (Eds.), Sports Public Relations and Communication (pp. 1-11). Elsevier: New York.

24. Hoover, J. (2013, February 21). Bowlsby’s against FCS blowouts, but doesn’t want to

mandate it in Big 12. Tulsa World online edition. Retrieved from http://www.tulsaworld.com/blogs/sportspost.aspx?Bowlsbys_against_FCS_blowouts_but_doesnt_want_to_mandate_it_in_Big_12/54-19159

25. Johnson, K. (2012, October 30). No surprises: Print readership declines, online

audience grows. Sacramento Business Journal online. Retrieved from http://www.bizjournals.com/sacramento/news/2012/10/30/newspaper-audience-report-circulation.html

26. Kian, E.M., Clavio, G., Vincent, J., & Shaw, S.D. (2011). Homophobic and sexist yet

uncontested: Examining football fan postings on Internet message boards. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(5), 680-99.

27. Kian, E.M., & Zimmerman, M.H. (2012). The medium of the future: Top sports

writers discuss transitioning from newspapers to online journalism. International Journal of Sport Communication, 5(3), 285-304.

28. Kuypers, J.A. (2002). Press bias and politics: How the media frame controversial

issues. Westport, CT: Praeger.

29. Leberton, G. (2012, September 9). For Patterson’s Horned Frogs, it was perfect star.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram online edition. Retrieved from http://www.star-telegram.com/2012/09/09/4242903/for-pattersons-frogs-it-was-perfect.html

30. Logue, A. (2012a, September 16). Iowa State football: Cyclones breeze past Western

Illinois 37-3. Des Moines Register online edition. Retrieved from http://www.desmoinesregister.com/

31. Logue, A. (2012b, September 9). Iowa State football: Cyclones seeking comfort zone

after uneven big game performance. Des Moines Register online edition. Retrieved from http://www.desmoinesregister.com/

32. McChesney, R.W. (1989). Media made sport: A history of sports coverage in the U.S.

In L.A. Wenner (Ed.), Media, Sports, & Society (pp. 49–69). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

33. McKee, A. (2001). A beginner’s guide to textual analysis. Metro, 127/128, 138-14.

34. McKillop, A. (2012, August 20). Correcting history: The first time an FCS (I-AA)

team defeated a ranked FBS (I-A) team. Football Geography online edition. Retrieved from http://www.footballgeography.com/?p=2171

35. Mizell, G. (2012, September 2). Oklahoma State football: Savannah State game

didn’t give OSU first-teamers much preparation. The Oklahoman online edition. Retrieved from http://newsok.com/oklahoma-state-football-savannah-state-game-didnt-give-osu-first-teamers-much-preparation/article/3706542

36. Northington, E.K. (1993). Split allegiance: Small-town newspaper community

involvement. Journalism of Mass Media Ethics, 7(4), 220-232.

37. Oates, T.P., & Pauly, J. (2007). Sports journalism as moral and ethical discourse.

Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 22(4), 332-347.

38. Palmer, T. (2012, August 30). Olathe North’s Doug Peete relishes chance to beat KU:

Several players on South Dakota State are from the Kansas City area. The Kansas City Star online edition. Retrieved from http://www.kansascity.com/2012/08/29/3786649/olathe-norths-doug-peete-relishes.html

39.Parchman, W. (2012a, September 14). Ex-China Spring QB Bell back home, football

in hand. Waco Tribune-Herald online edition. Retrieved from http://www.wacotrib.com/sports/baylor/169727246.html

40. Parchman, W. (2012b, September 16). 2nd-half adjustments save Baylor against Sam

Houston. Retrieved from http://www.wacotrib.com/sports/baylor/169937956.html

41. Potrykus, J. (2013, February 12). Barry Alvarez: Big Ten agrees no more FCS

opponents. Milwaukee-Wisconsin Journal Sentinel online edition. Retrieved from http://www.jsonline.com/blogs/sports/190943281.html

42. Reader, B. (2006). Difference that matter: Ethical difference at large and small

newspapers. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(4), 1-10.

43. Reinardy, S. (2005). No cheering in the press box: A study of intergroup bias and

sports writers. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, New York City. Retrieved from http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p13810_index.html

44. Rohlinger, D.A. (2002). Framing the abortion debate: Organizational resources, media strategies, and movement-countermovement dynamics. The Sociological Quarterly, 43(4), 479-507.

45. Rouner, D., Slater, M., Long, M., & Stapel, L (2009). The relationship between

editorial and advertising content about tobacco and alcohol in United States newspapers: An exploratory study. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(1), 103-118.

46. Rowe, D. (2007). Sports journalism: Still the ‘toy department’ of the news media.

Journalism, 8(4), 385-405.

47. Salwen, M., & Garrison, B. (1998). Finding their place in journalism: Newspaper

sports journalists’ professional ‘problems’. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 22(1), 88-102.

48. Sander, L. (2011, June 15). 22 Elite college sports programs turned a profit in 2010,

but gaps remain, NCAA reports says. The Chronicle of Higher of Education online. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/22-Elite-College-Sports/127921/

49. Sanderson, J. (2011). To tweet or not to tweet…: Exploring Division I athletic

department social media policies. International Journal of Sport Communication, 4(4), 492-513.

50. Schudson, M. (2001). The objectivity norm in American journalism. Journalism,

2(2), 149-170.

51. Schultz-Jorgensen, S. (2005). The world’s best advertising agency: The sports press’

International Sports Press Survey 2005. Copenhagen: House of Monday Morning: Play the Game. Retrieved from http://playthegame.org/upload/Sport_Press_Survey_English.pdf

52. Sheffer, M.L., & Schultz, B. (2010). Paradigm shift or passing fad? Twitter and sports

journalism. International Journal of Sport Communication, 3(4), 472-484.

53. Slater, A. (2012, September 8). Rapid reaction: A quick look at OU’s domination of

Florida A&M. The Oklahoman online edition. Retrieved from http://blog.newsok.com/ou/2012/09/08/rapid-reaction-a-quick-look-at-ous-domination-of-florida-am/

54. Smith, C. (2012, December 19). College football’s most valuable teams: Texas

Longhorns on top, Notre Dame falls. Forbes online edition. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/chrissmith/2012/12/19/college-footballs-most-valuable-teams-texas-longhorns-still-on-top/

55. Soley, L.C., & Craig, R.L (1992). Advertising pressures on newspapers: A survey.

Journal of Advertising, 21(4), 499-508.

56. Sparkes, A. (1992). Writing and the textual construction of realities: Some challenges

for alternative paradigms research in physical education. In A. Sparkes (Ed.), Research in physical education and sport: Exploring alternative visions (pp. 271-297).

57. Staples, A. (2013, May 14). Analyzing 10 years of committee decisions had playoff

been in pace. Sports Illustrated online. Retrieved from http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/college-football/news/20130514/playoff-selection-committee/

58. Stevenson, S. (2012, September 9). TCU guards against overconfidence after opening

blowout. Fort Worth Star-Telegram online edition. Retrieved from http://www.star-telegram.com/2012/09/09/4244494/tcu-guards-against-overconfidence.html

59. Storch, G. (2010, February 26). The pros and cons of newspapers partnering with

‘citizen’ journalism networks. The Online Journalism Review. Retrieved from http://www.ojr.org/ojr/people/gstorch/201002/1826/

60. Thamel, P. (2012, November 19). Maryland to leave ACC for Big Ten in a move

driven by cable revenue. Sports Illustrated online. Retrieved from http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/2012/writers/pete_thamel/11/19/maryland-big-ten-realignment/index.html

61. Temple, J. (2012, August 30). Money makes FCS-FBS mismatches go round.

FoxSportsWisconsin.com. Retrieved from http://www.foxsportswisconsin.com/08/30/12/Money-makes-FCS-FBS-mismatches-go-round/landing_badgers.html?blockID=782187

62. Tuchman, G. (1978b). Making news: A study in the construction of reality. New

York: Free Press.

63. Tucker, T. (2012, September 13). Money game: UGA-Florida Atlantic pays off for

both sides. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution online. Retrieved from http://blogs.ajc.com/uga-sports-blog/2012/09/13/money-game-uga-florida-atlantic-game-pays-off-for-both-sides/

64. Vincent, J., & Crossman, J. (2008). Champions, a celebrity crossover, and a

capitulator: The construction of gender in broadsheet newspapers’ narratives about selected competitors during “The Championships.” International Journal of Sport Communication, 1(1), 78-102.

65. Wenner, L.A. (1989). Media, sports and society: The research agenda. In L.A.

Wenner (Ed.), Media, Sports and Society (pp. 13-48). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

66. Werner, J. (2012, September 11). Dixon, Baylor players anxious, ready to test Sam

Houston St. Waco Tribune-Herald online edition. Retrieved from http://www.wacotrib.com/sports/baylor/169268766.html

67. West Virginia Press Association (2012). 2012 West Virginia Press Association

newspaper directory online edition. Retrieved from http://www.wvpress.org/images/Directory/2012/2012Directory_small_r.pdf

A Countywide Program to Manage Concussions in High School Sports

Submitted by Gillian Hotz Ph.D, Ashlee Quintero, BSc, Ray Crittenden, MSc, Lauren Baker, David Goldstein and Kester Nedd, DO

ABSTRACT

Background: With the national spotlight on concussions sustained in contact sports, this Countywide Concussion Program addresses the unique challenges presented to public and private high schools in order to increase concussion awareness, identification, and management.

Methods: The Miami Concussion Model (MCM) was developed with a standard protocol that includes; formation of a task force of stakeholders, concussion education and training to coaches, athletic trainers, and athletes; baseline ImPACT™ testing, the facilitation of ‘return to play’ decisions with effective medical treatment, and the development and implementation of a concussion injury surveillance system.

Results: The program has been successfully implemented in about 40 high schools in Miami-Dade County (MDC) over the last two years. The MCM provided baseline testing for 18,357 student-athletes, trained over 100 coaches and 40 athletic trainers, and most recently provided concussion education to high school football athletes. Since 2011, the concussion clinic has treated a total of 216 high school athletes and the surveillance system tracked 198 student athletes.

Conclusion: The MCM aims to assist in the prevention of concussions, improve player safety limiting school liability by providing a countywide concussion management program. The program is funded primarily by private donations and the support of multiple stakeholders. With about 48 States passing concussion legislation, the MCM can be used as a model for other counties to address the need for a concussion management program.

Applications in Sport: Schools with athletic programs need to implement a system to correctly manage and prevent concussive injuries both to protect their athletes and to minimize liability. The development of the MCM and protocol with the support of the leadership of the School Board allows for high schools to take a proactive approach in improving concussion management for their athletes.

INTRODUCTION

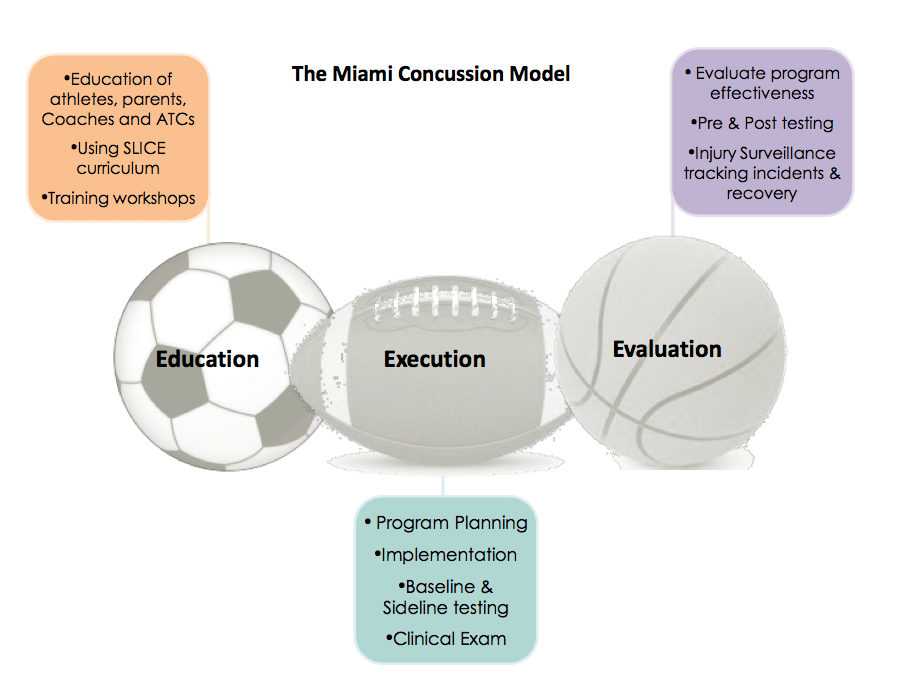

With the national spotlight on concussions in sports, key stakeholders worked together to develop a concussion model, a standard countywide concussion care protocol, and a surveillance system to improve concussion management and to reduce the incidence of sports¬-related concussions at the high school level. In 2011, a student-¬athlete who had sustained multiple concussions playing soccer spearheaded the initiative to create a taskforce to address the management of concussions. A taskforce was implemented consisting of physicians, community leaders, school officials, and concerned parents. The combination of these stakeholders’ backgrounds created a diverse team with unique resources to create a program utilizing a public health approach toward preventing concussions. The Miami Concussion Model (MCM) was designed as a 3-E model (Education, Execution, and Evaluation) outlining phases for program development, implementation, and evaluation (Figure 1).

The program has been successfully implemented in 40 high schools in Miami-Dade County (MDC), baseline testing 18,357 student-athletes over two years. The goals of the MCM are to provide a comprehensive and centralized concussion care program to 1) increase concussion awareness and identification through education and training; 2) facilitate the return to play decision with effective medical treatment which includes baseline neurocognitive testing; and 3) implement a standardized concussion care protocol and concussion injury surveillance system to assist in the prevention of concussions, improve player safety, and limit school liability.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the leading cause of injury¬-related death in children and young adults in the United States and other industrialized countries. A concussion is a type of brain injury caused by a bump or blow to the head that alters cognitive functioning. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated annual sports¬ related concussion incidence is between 1.6 and 3.8 million (Centers for Disease Control, 2010; Coronado et al., 2011; Leibson et al., 2011). Sports is the second leading cause for TBIs after motor vehicle accidents among people aged 15 to 24 years old (Nanda et al., 2012). Studies demonstrate short and long term effects of concussions can be serious and occasionally fatal (Daneshvar et al, 2011; Iverson et al., 2006; Lovell et al, 2003). Most recent public concern has focused on the relationship between Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a progressive degenerative disease of the brain found in an athlete’s brain post-¬mortem, with a history of multiple symptomatic concussions as well as asymptomatic, repeated sub¬-concussive hits to the head (McKee et al., 2009). As a result of high-profile athletes reporting injuries there has been increased media attention emphasizing the effects of mild traumatic brain injury and concussions in athletes. Beginning in 2009, 48 states nationwide have passed youth sports concussion legislation that requires athletes to be immediately removed from play if a head injury is suspected and then cleared by a licensed medical professional before returning to sport after a head injury.

METHODS

In order to prevent and reduce the consequences of injuries, the CDC recommends the public health approach; describing the problem, identifying the risk and protective factors, developing and testing preventative interventions and strategies, and ensuring widespread adoption of the interventions and strategies (Sleet et al., 2003). This model was used to develop the MCM, a 3E model that includes components of Education, Execution, and Evaluation. The model and the protocol presented in this paper are now being implemented across the county.

Education

The issue of sports related concussions was identified within the MDC community by the University of Miami Concussion Program (UMCP) obtaining accurate injury rates. The number of affected individuals was calculated based on the participation in contact sports in the community. In M¬DC there are 36 public high schools with approximately 15,000 students participating in interscholastic sports annually. M¬DC public high schools had an enrollment of 102,582 students for the 2011¬ and 2012 school years; therefore 14.6% of public high school students in MDC participated in sports and were affected/at risk for sports¬ related concussions. This excluded the students that participated in physical education courses who were also at risk (Miami-¬Dade Public Schools Research Services [M-DPSRS], 2011). As perceptions regarding concussion started to change in the county and awareness increased due to media attention, M¬DC school officials became open to discussion to improve their concussion management plan. This allowed for meetings with key personnel involved with high school athletes (athletic directors, coaches, athletic trainers, physical education teachers, etc.). These meetings were very important in that they revealed their knowledge and their experience with sports concussions and their thoughts of how to improve management for their athletes.

Review of existing sports concussion management protocols and resources in the community was conducted to 1) determine if any current concussion management programs or plans existed, 2) obtain information from local emergency rooms and physicians’ offices relevant to concussion planning, and 3) identify how those individuals managed concussion in youth sports and where they were referring their patients for specialized follow-¬up care. That information taken from multiple sources (leagues, parks, schools, state laws, and local medical care centers) was summarized regarding the issue of sports concussions within the community. For example, most high school aged (13-19 years) students in the community participated in interscholastic sports versus park recreational leagues; the majority of injuries occur between the months of August and January during football season because football teams have the largest number of athletes. Being well informed on the issues of concussion management allowed a focused approach toward building a concussion care program for the community via the MCM.

The UMCP was then able to identify the weaknesses in each phase of concussion management and propose resolutions to strengthen each area. A community task force was developed that consisted of key stakeholders from different agencies involved in concussion management. This included school board representatives, first responders to the injury, medical providers, and community leaders.

Most recently UMCP has partnered with the Sports Legacy Institute and joined their community education program through their Sports Legacy Institute Community Educator Program (SLICE). SLICE is a fun, interactive concussion education program that teaches young student-athletes about concussions through discussion, video, and interactive games (Sports Legacy Institute [SLI], 2013). Currently, a modified version of SLICE, which is a 30-minute power point presentation, is being used to educate high school football players.

Support and approval for concussion planning was obtained from the various constituencies for the community task force and was followed up with research of each district, county, and state policy pertaining to sports concussions for high school athletes. Verification of regulations was implemented and continuously updated to allow consistency with the newest management protocols as outlined in the Consensus Statement from the International Committee on Sports Concussions (McCrory et al., 2008). Legislation has passed in 48 states across the country requiring student athletes to receive written medical clearance before returning to the playing field. These state laws include the requirement that athletes, parents, and coaches receive concussion education. Prior to 2011 limited regulations existed in the MDC community, so the UMCP collaborated with school board officials to formulate a plan to involve relevant personnel from the athletic department. In MDC, the school board’s Director of Athletics assisted with the planning and implementation as one of the critical task force members, her cooperation and support ensured feasibility and assistance with the school board approval. The UMCP worked directly with the schools and school board to improve the success of developing a standard program that could reach all athletes. In M¬DC Public Schools, each school has a certified athletic trainer (ATC) that works full-time at his/her school and is an employee of the School Board. The unique qualifications of ATCs made them the most appropriate person to collaborate with upon implementing the program in each school. The Director of Athletics for MDC public schools supported these efforts and began communication between UMCP and the ATCs. Even where certified athletic trainers are not readily available, athletic coaches or the school nurse were trained to implement the program. In March 2011 the ATCs and Coaches were provided with a comprehensive Concussion Management and Training Workshop by UMCP.

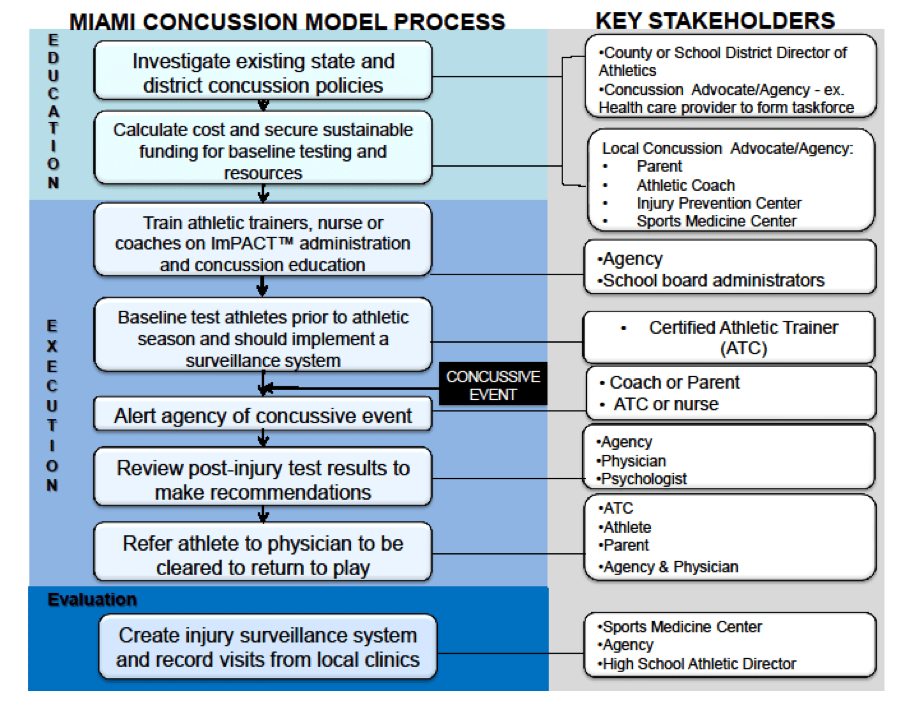

Finally, a plan was developed for funding and sustainability of the program. The first step was to review any existing funding mechanisms and potential new resources to support the implementation of a comprehensive management program. The plan included 1) staff/operations costs and baseline neurocognitive testing for all student athletes; and 2) implementing the centralized concussion care program as an investment in the safety of athletes that improves the prevention of concussions¬¬ by facilitating ongoing training and education which reduces liability when administered properly. However, in most public school systems budgets do not include a plan for concussion prevention/care, and funding can be difficult to find. The cost of operating such a program will vary depending on the size of the school district and the structure of the program. The process described (see Figure 2) demonstrates the development of an infrastructure for operation of the model. In MDC it was feasible for the UM Concussion Program under the KiDZ Neuroscience Center (KNC), which is a center devoted to improving the quality of care and advances in research and prevention of traumatic and acquired brain and spinal cord injury in children to partner with the MDC Public School Board. Additionally, since the MDC school board employs their own ATCs, training was provided for baseline neurocognitive testing of athletes playing contact sports and was added to their existing duties. In M¬DC, ImPACT™ (Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing) is utilized because it is an evidence ¬based assessment that has been widely used and validated (Schatz et al., 2006). ImPACT™ is a 20-minute online computer exam consisting of five sections that assess memory, reaction time, non-verbal and verbal problem solving, and attention span. Baseline ImPACT™ scores are valid for four years for each athlete during their high school years, which reduces the annual cost of purchasing new exams. UMCP receives a charitable donation from a private high school annually that covers the price of purchasing baseline tests by volume for reduced pricing for all 36 public high schools in the county. The private schools buy their own licenses. The Director of the UMCP is also a Credentialed ImPACT™ Consultant with training that coordinates all the baseline testing. If an athlete sustains a concussion then they are retested by the ATC within 48-72 hours and the Director of the UMCP is notified and recommendations made and clinic visits scheduled.

Execution

Once approval by the different agencies was granted, the execution phase of the MCM was initiated. The Countywide Concussion Care Protocol was developed to create a standard protocol for the concussion management of high school athletes (Figure 2). The first phase involved training and educating appropriate staff about concussions in sports and also how to administer baseline neurocognitive tests. The ATCs and school nurses were educated about concussion management and worked closely with an expert in concussion management to provide accurate information and to respond to questions. Prior to this program the Director of the UMCP taught a mandatory educational and training workshop for ATCs and Coaches that was expanded and continues. Other school professionals like nurses that may be involved in management of care for student athletes are trained annually on the concussion protocols as guidelines and recommendations change. In MDC, sideline assessment requirements include the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 2 (SCAT2) and the King-Devick Test. The SCAT2 represents a standardized method of evaluating athletes aged 10 and older for concussion injuries through a series of cognitive questions and physical assessments (McCrory, 2009). The King-Devick Test is a rapid visual screening tool that is used to confirm suspected concussions, the athlete is asked to read numbers from the cards in sequence without errors as fast as possible. The athlete’s post-injury performance is compared to their pre-season baseline result (Galetta et al., 2011). Both of these assessments are utilized on the sidelines to verify suspected concussion symptoms and provide an objective confirmation of the injury. Protocols and guidelines are reviewed and updated annually to be consistent with national and state requirements and the latest medical research recommendations. During the pre¬-season training workshop by the UMCP, ATCs were trained on evaluating and administering baseline assessments to athletes. Two assessments require baseline results, ImPACT™ and the King-Devick test; athletes are tested prior to the start of contact drills to obtain accurate baseline results. In MDC, a list of testing guidelines was created for the school staff to reference throughout the year. After all athletes are tested, the ATCs, coach, or nurse contact the Director of the UMCP to verify that all baseline tests are valid before athletes are introduced to contact activities.

The MCM incorporates medical evaluation of the concussed athlete. UMCP works in conjunction with local physicians and other psychologists to assess the physical and neurocognitive consequences of the injury. The athletes receive comprehensive medical care, which is mandatory for clearance to play. UMCP provides a comprehensive concussion management program assessing the athlete’s medical, cognitive, and psychological well being during the recovery process. The pressure that athletes have to return to their pre¬-morbid academic and athletic levels can be overwhelming for an adolescent, particularly when their peers cannot understand the extent of their injury. The ImPACT™ neurocognitive computer test results coupled with a thorough clinical assessment aids the medical team in making an accurate prognosis and providing the athlete with confidence when returning to play. The UMCP medical team works directly with the ATCs to communicate the status of the athlete’s recovery.

Evaluation

When evaluating the model UMCP researchers examined individual school compliance as well as overall effect of program implementation on head injury rates in the county. The concussion protocol dictates that a school staff member will document the athlete’s immediate symptoms and details of the injury incident, which can be seen in Figure 2 (Evaluation). The ATC, coach, or nurse is to document each incident and keep accurate records, including: sideline assessment results from the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 2 (SCAT2) or the King¬-Devick test (McCrory et al., 2008). Within 24¬-72 hours of the injury the athletic trainer, coach, or nurse would have administered a post¬-injury test to the injured athlete, reported the incident to the program coordinator and sought medical attention for the athlete.

Various methods to collect data can be utilized including tracking patients in local clinics and emergency departments, integrating an injury reporting system and continued follow-¬up with the school personnel. In MCM the records of concussion patients treated at UMCP are collected and an online concussion injury surveillance tool has been developed. The online injury¬ reporting form collects relevant details of the concussive incident including age, gender, sport, mechanism of injury, history of concussion, equipment that was worn at the time of injury, and geographical region within the county. It is necessary to collect accurate data surrounding each injury to better identify the specific issues occurring whether it is equipment failure, environmental, incorrect coaching, etc. The involved agencies collaborated to evaluate the effectiveness of the program after its implementation.

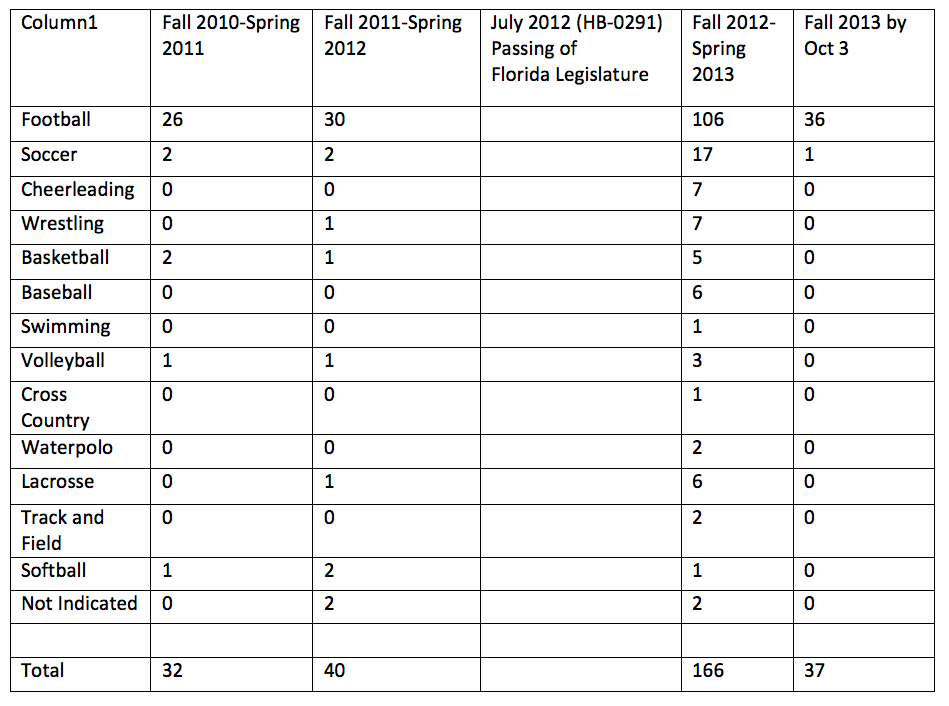

The Florida State Legislature passed House Bill 0291 in July of 2012 to ensure there are policies relating to the nature and risk of concussion and head injury in youth athletes requiring informed consent for participation in practice or competition and removal from practice or competition under certain circumstances, and written medical clearance to return. Pre-Legislation data from concussions reported in High School Sports based on age, sex, and ethnicity were obtained through the surveillance system. The pre-legislation results for all sports at 36 MDC High Schools for the 2010-2011 school year reported 32 concussions. For the following school year 2011-2012, still reported as pre-legislation, 40 concussions were reported. The most significant increase in reporting was for the school year 2012-2013, which was post-legislation data obtained after the passing of HB 0291 in July 2012. The 2012-2013 school year reported 166 concussions, a four-fold increase in concussion reporting. (Table 1)

Table 1. Surveillance Data

Concussion reporting for all sports in 36 Miami-Dade County Public High Schools

The marked increase in reporting after the implementation of HB-0291 is attributed to increased awareness and the addition of a standard management protocol. The program has been successfully implemented in about 40 high schools (36 public and 4 private) in MDC. The MCM provided ImPACT™ baseline testing for 18,357 student-athletes, trained over 100 coaches and 40 athletic trainers, and most recently provided concussion education to high school football athletes. Data obtained from the UMCP clinic reports that in 2010, prior to the implementation of the standard protocol, 44 high school athletes from both public and private schools were treated for sports concussions during the fall athletic season (August-¬January). In 2011, post¬-implementation of the model, 61 athletes sought treatment for concussions. During the 2012 fall season and up to the present time, 155 ¬athletes were treated in the same clinic for a sports-¬related concussion, which included all sports for a total of 216 athletes treated. There are some athletes that return to their pediatricians or family doctors for their care and for clearance for return to play however the ATC at their school still follows the protocol and will enter data in the surveillance system. The chief complaints that athlete’s reported during clinic visits included; headaches, dizziness, fatigue, visual disturbance, and concentration issues. Most of these physiological symptoms were accompanied by cognitive deficits, which affected their academic performance. The clinic has developed a protocol for gradual return to play which includes exertion activities from low to high as tolerated and also return to class and academic work with specific accommodations. The University subjects’ review board approvals were obtained prior to collecting any data. The majority of the concussive injuries occurred in an MDC high school setting or at a school¬ sanctioned athletic event. In 2012, 198 high school concussion injuries were reported through a concussion injury surveillance system that the ATCs have been trained to use, 183 (92.4%) of those reported incidences occurred at a school or at a school sponsored athletic event.

DISCUSSION

The MCM presented here was implemented in MDC in 2011. From this pilot evaluation of the model it was determined to be effective in increasing the number of concussions identified, reported, and also treated at the UMCP clinic. Also a centralized standard protocol was now in place across the county allowing for better communication and compliance for reporting by the high school ATCs. This model, or a modified version, can be implemented to centralize concussion management in other counties and communities across the country. There is a unified need in every community for the development of concussion care protocol with the ever-increasing awareness and liability involved in high school sports.

CONCLUSION

Concussions affect all aspects of the student-¬athlete and therefore management of an injured athlete should be comprehensive and include psychological assessments, neurocognitive testing, academic support, and a physiological examination. A comprehensive program that combines education, baseline neurocognitive testing, clinical care and evaluation is believed to be most beneficial to maximize the effectiveness of such a program. The MCM outlined in this paper is designed to be a guideline that can be adapted to the needs of different communities. Data will continue to be collected and analyzed to evaluate the effectiveness of this program. With limited coordination and low cost for baseline testing it is important to have a concussion management program in place.

BARRIERS TO IPLEMENTATION

Since the MCM was developed with the consensus of key stakeholders, there has been little resistance. The model presented has recently been developed and is going through continual evaluation. While the preliminary data seems promising, we will continue to evaluate this model over the next few years. Since the identification of a concussive event relies on the reporting of injuries by the ATCs at each high school their support and implementation of the program is critical in the success of the program. The staff of the UMCP suspected that the number of concussive injuries was still under¬reported in the first year, however now with the passing of the Concussion Legislation in July 2012, reporting has increased. Also with continued training and education workshops and the centralized system this should improve compliance. Since MDC has ATCs that all work for the school board it is much easier to implement such a program. In other cases where the ATCs work for medical or rehab facilities they need to be compensated for their time in supervising and administering of the baseline ImPACT™ testing. If they are not able to participate a school nurse could be trained. Funding for the MCM will continue through a commitment made by the fundraising efforts of one private school in MDC, however there are other ways to budget for such a program; Parent¬ Teacher Association fundraisers, booster club events, corporate support, local sports teams sponsorship, or a nominal fee inclusive in yearly athletic dues.

APPLICATIONS IN SPORTS

The increased awareness of concussions and their effects on the developing brain have created a culture change in sports. Schools with athletic programs need to be encouraged to implement a system to correctly manage and prevent concussive injuries both to protect their athletes and to minimize liability. The development of the MCM and protocol with the support of the leadership of the School Board allowed for the high schools in MDC to take a proactive approach in improving concussion management for their athletes. The Baseline neurocognitive computerized testing ImPACT™ provided an objective measure that with the clinical exam assisted in determining a beneficial recovery plan for the athlete and providing a plan for the school to limit their liability while better caring for their student-¬athletes while identifying and preventing injuries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kaplan and the UHealth Sports Medicine Clinic and Staff, also Cheryl Golden, Director of Athletics for the Miami-Dade County School Board and all the Miami-Dade County Certified Athletic Trainers. We would also like to thank Ransom Everglades School, David Goldstein and the Goldstein Family for their initial and continued support of the UMCP.

REFERENCES

1. Centers for Disease Control. (2010). National Center for injury prevention & control: Traumatic brain injuries. Heads up: Concussions in high school sports. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/concussion/sports/index. html

2. Coronado, V.G., Xu, L., Basavaraju, S.V., McGuire, L.C., Wald, M.M., Faul, M.D.,…Hemphill, J.D. (2011). Surveillance for traumatic brain injury-¬related deaths–¬¬United States, 1997¬-2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries, 60(5), 1¬-32.

3. Daneshvar, D.H., Riley, D.O., Nowinski, C.J., McKee, A.C., Stern, R.A., & Cantu, R.C. (2011) Long¬term consequences: Effects on normal development profile after concussion. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 22(4), 683-700.

4. Galetta, K.M., Brandes, L.E., Maki, K., Dzuenuabwucz, M.S., Laudano, E., Allen, M.,…Balcer, L.J. (2011). The King¬-Devick test and sports related concussion: Study of a rapid visual screening tool in a collegiate cohort. Journal of Neurological Science, 309(1¬2), 34¬-39

5. Iverson, G.L., Brooks, B.L., Collins, M.W., & Lovell, M.R. (2006). Tracking neuropsychological recovery following concussion in sport. Brain Injury, 20(3), 245-¬252.

6. Leibson, C.L., Brown, A.W., Ransom, J.E., Diehl, N.N., Perkins, P.K., Mandrekar, J., & Malec, J.F. (2011). Incidence of traumatic brain injury across the full disease spectrum. Epidemiology. 22(6), 836-¬844.

7. Lovell, M., Collins, M., Iverson, G., Field, M., Maroon, J., Cantu, R., & Podell, K. (2003). Recovery from mild concussion in high school athletes. Journal of Neurosurgery, 98(2), 296-¬301.

8. McCrory, P. (2009). Sport concussion assessment tool 2. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 19(3),452-452.

9. McCrory, P., Meeuwisse, W., Johnston, K., Dvorak, J., Aubry, M., Molloy, M., & Cantu, R. (2009). Consensus statement on concussion in sport – the 3rd international conference on concussion in sport, held in Zurich, November 2008. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 16(6), 755-¬763.

10. McKee, A., Cantu, R., Nowinski, C., Hedley-Whyte, E.T., Gavett, B.E., Budson, A.E.,…Stern, R.A. (2009). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: Progressive tauopathy following repetitive head injury. Journal Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology, 68(7), 709-735.

11. Miami-¬Dade Public Schools Research Services. (2011) Statistical Highlights, 2010-2011[Data File]. Retrieved from http://home.dadeschools.net/files/Statistical Highlights.pdf.

12. Nanda, A., Kahn, I.S., Goldman, R., & Testa, M. (2012). Sports Related Concussions and the Louisiana Youth Concussion Act. The Journal of the Louisiana State Medical Society, 164(5), 246-250

13. Schatz, P., Pardini, J.E., Lovell, M.R., Collins, M.W., & Podell, K. (2006). Sensitivity and specificity of the ImPACT Test battery for concussion in athletes. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21(1), 91-99.

14. Sleet, D.A., Hopkins, K.N., & Olson, S.J. (2003). From Delivery to Discovery: Injury Prevention at CDC. Health Promotion Practice, 4(2), 98-102.

15. Sports Legacy Institute. SLI Community Educators (2013). Retrieved from http://sportslegacy.org/education/slice.

The Impact of Hip Rotator Strength Training on Agility in Male High School Soccer Players

Submitted by Jesse Obed Nelson and Mark DeBeliso

ABSTRACT

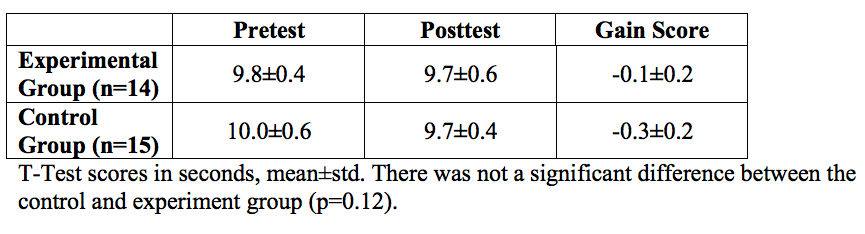

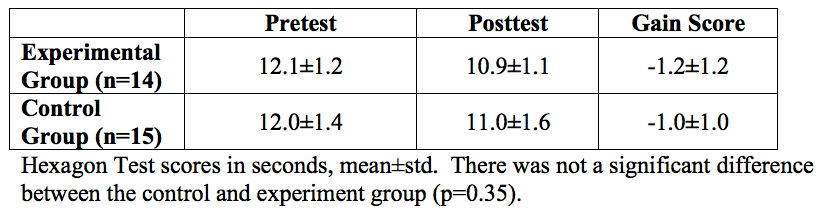

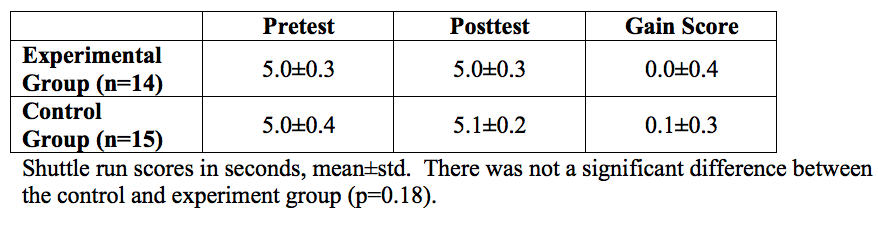

The strength of the muscles surrounding a joint contributes to the stability of the joint. The stability of a joint provides the foundation for large muscle groups to perform high speed forceful actions. The purpose of this study was to examine if strengthening of the hip rotator muscles could improve measures of agility. Twenty-nine male high school soccer players were recruited to participate in a 9-week matched pair study. The control and the experimental group participated in regular weight training and soccer practice. Additionally, the experimental group performed three sets of the hip rotator exercises using latex chords (medial and lateral rotation) twice per week with both legs. The dependent variables were the T-Test, the Hexagon Test, and the 20-Yard Shuttle Run. All athletes were pre- and post-tested on each of the agility drills. A gain score was then calculated as the difference between pre- and post-test agility scores. An independent t-test was used to determine if there were any differences (p < 0.05) between the experimental and control groups. Statistical analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups for T-test (p=0.12), Hexagon test (p=0.35), and 20-yard shuttle run (p=0.18). The research hypothesis, which stated that adding hip strengthening exercises for the experimental group would produce faster times on the agility tests, was rejected. Possibly the volume of training, which often included three hours of exercise and practice per day, rendered the additional hip strengthening exercises insignificant. Repeating the experiment in the off-season with lower training volume might produce different results.

INTRODUCTION

In sport and physical therapy there is not much time spent in training the medial and lateral rotators of the hip, while medial and lateral rotators of the arm (rotator cuff) are regularly exercised (15, 17). The deep inner muscles of the hip are often neglected and overlooked in the development of training programs for all types of sport.

Field sports which might benefit from strengthening of the hip rotators are those which require movements of agility (e.g. soccer, football, lacrosse, rugby, and basketball). Agility requires rapid change of direction. This is where stronger hip rotator muscles may help athletes. An increase in performance might be experienced as a result of stronger hip rotator muscles.