Authors: Paula Murray(a), Rhiannon Lord(b), & Ross Lorimer(b)

(a) Loughborough College, UK

(b) Abertay University, UK

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Ross Lorimer

Abertay University

Dundee, UK, DD1 1RG

Ross.Lorimer@Abertay.ac.uk

+44 (0)1382 308426

The influence of gender on perceptions of coaches’ relationships with their athletes: A novel video-based methodology

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of coach and athlete gender on perceptions of a coach through the use of a novel video-based method. Forty-one participants (16 males, 25 females, Mage=32.76 SD= ± 11.57) watched four videos depicting a coach and an athlete having a conversation about the athlete’s de-selection from a squad. Each video featuring different gender combinations of the coach and athlete. Participants rated the coach on perceived relationship quality and perceived empathy. Analysis showed a main effect for coach gender with female coaches being rated higher than male coaches for relationship quality and empathy, and a main effect for athlete gender with all coaches perceived as displaying a greater level of affective empathy when paired with a female athlete. Coaches need to be aware that their actions may be interpreted differently based on their gender and that of the athletes they are working with. This could potentially impact on coach effectiveness and the outcomes of their behaviours.

Keywords: Coaching, Perceptions, Empathy, Relationship quality

INTRODUCTION

Coaches play a fundamental function in sport, working closely with athletes to develop physical, technical and psychological improvements through the application of their own knowledge and expertise (Lyle, 2002). The coach’s role is to enable an athlete to develop higher levels of performance that the athlete may not otherwise be able to achieve. Yet, the knowledge and expertise of the coach is not the sole determining factor in the success of an athlete. Sport is a shared experience, a complex social environment constructed from subjective interpersonal perceptions (Wylleman, 2000). As such, how the coach’s actions are interpreted may impact on the effectiveness and ultimately success of the coach. The interaction between coaches and athletes is in part influenced by subjective interpersonal perception.

Individuals rely on a series of mental schema regarding roles and situations on which to base their perceptions of others (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). While these schemas contain information that individuals can use in order to increase the accuracy of perceptions, these schemas can also contain biases and stereotypes such as expectations of individuals due to them being assigned to a particular group (Augostinos & Walker, 1999). Stereotypes or biases become widely accepted when a disproportionate number of a specific social group (e.g., gender, race, nationality) are perceived to be involved with a particular role, for example sports coaching (Wood & Eagly, 2012). The behaviours which are associated with this role can then come to influence subjective beliefs about the perceived characteristics of those within that group, essentially creating a stereotype or bias regarding a specific group (Gawronski, 2003).

Effective coaching takes place when an athlete’s autonomy is supported (Becker, 2009). However, traditionally, coach-athlete interactions have been described as a situation in which the coach’s control is absolute (Burke, 2001). The coach’s role, in which they impart their knowledge and technical expertise to the athlete, creates a situation in which the athlete is conditioned to submit to the direction of the coach. Essentially, the role of the coach is perceived to be that of a leader and of authority, conversely the role of the athlete is seen to be that of a follower (Burke, 2001). Further, Tomlinson and Yorganci (1997) suggest that the traditional roles of the coach and the athlete as leader and follower are particularly pronounced where a male coach is working with a female athlete.

Eagly and Karau (2002) have demonstrated that women in leadership positions, such as sports coaching, tend to be rated as less effective in comparison to men in the same position. This may be in part a result of the fact that many women in leadership roles place greater emphasis on sensitivity, opposed to men who tend to be more likely to focus on power (Epitropaki & Martin, 2004). As such, woman will often violate the traditional roles of the leader/sports coach and in turn be seen as less effective. Conversely, when women are in positions of leadership and demonstrate agentic traits, more in line with the traditional role of a coach, they are often viewed as less likable (Rudman et al., 2011), likely as a result of them violating their traditional gender role.

Another widely held stereotype is often that women possess a greater insight and sensitivity into the feelings of others than men (Ickes, Gesn, & Graham, 2000). This suggests that people as a whole believe that there is a differential ability between genders; and so women as a group possess some inherent ability/skill that makes them more empathic than men. However, Ickes, Gesn and Graham (2000) have argued that this only occurs when the gender-role is made salient. As such, in situations where the gender-role is violated (e.g., a female coach working with a male athlete) this perception would be expected to be less prominent (Kamphoff, 2010).

Gender can impact on the perception of leadership roles such as sports coaching. For example, Manley et al. (2010) showed that based upon only initial impressions, athletes typically will perceive female coaches to be less competent than male coaches. However, it is important not to overlook that coaching is a social interaction involving both the coach and the athlete. As such it would seem sensible to suggest that the interaction of both the coach’s and the athlete’s gender needs to be investigated.

Magnusen and Rhea (2009) used a hypothetical male and female strength and conditioning coach this demonstrated that male athletes were more comfortable with a male coach and exhibited negative attitudes towards female coaches, while Blom et al. (2011) infers that female coaches report that male athletes continually test them as they feel they have to constantly portray a strong persona. Conversely, Magnusen and Rhea (2009) showed that female athletes had no preference or difference in attitudes regarding the gender of their coach. However, Lorimer and Jowett (2010) have shown that a male coach working with a female athlete, a situation that reinforces both the traditional gender and sport-roles (male leader, female follower), was more effective than other gender mixes such as a male coach working with a male athlete, which both supports (male leader) and violates (male follower) traditional gender-roles.

The current study investigated how the gendered interactions of coaches and athletes influences perceptions of a coach and the quality of the coach-athlete relationship using a novel video-based methodology. It was hypothesized that gender mixes that reinforce traditional roles (e.g., male coach working with a female athlete) would be perceived as demonstrating higher relationship quality. Additionally, it was hypothesized that although female coaches would be perceived as having greater empathy than male coaches, this would be significantly lower when the gender mix violated traditional roles (i.e., the female coach is working with a male athlete).

METHODS

Participants

Forty-one participants (16 males, 25 females, Mage=32.76 SD= ± 11.57) were recruited from a range of team and individual sports. Participants had been involved in their sport for an average of 10.5 years (SD= ± 7.3) and covered a range of performance levels (recreational = 40%, regional = 30%, national = 18%, and international = 12%). Participants were approached using a variety of means including telephone, letter and email, and were invited to take part in an investigation examining how coaches and athletes interact.

Creation of Videotape stimulus

Two male and two female actors were recruited to depict a male and female coach, and, a male and female athlete. Actors were supplied with standardised clothing (tracksuits) to wear, followed the same script, and their facial expression, body language and position were monitored and kept consistent. Footage was used to edit create ‘identical’ 3-minute long videos. These included an opening scene, main conversation and an ending that depicted a coach and an athlete having a private conversation about the athlete’s de-selection from a sports squad for an upcoming competition. Each video differed in that they depicted one of four possible combinations of the genders of the coach and the athlete (i.e., male/male, female/female, male/female, female/male).

Measures

Perceived relationship-quality. Participants perceptions of the quality of the relationship between the coach and the athlete depicted in each video were measured using an adapted version of the Coach-Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART-Q; Jowett & Ntoumanis, 2004). The questionnaire is made up of eleven statements which are divided into three subscales Closeness (4), Commitment (3) and Complementarity (4). The scale range is from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This scale measures the meta-perspective of the participant regarding the coach (i.e., how an individual believes the coach perceives the athletic relationship). Normally this questionnaire is completed by an athlete working with a coach regarding their own relationship; in this case the questionnaire was modified to reflect an inference about the coach’s beliefs about the athlete depicted in the video. Three subscales were assessed: Closeness; the coach’s liking, trust and respect for the athlete (e.g., ‘The coach likes the athlete’). Commitment; the coach’s dedication to the athlete and intent to continue working with them (e.g., ‘The coach believes that the athlete’s career is promising with him/her’). Complementarity; the coach’s co-operative behaviors, responsiveness and friendliness towards the athlete (e.g., ‘The coach is ready to do his/her best’). For this sample, the Cronbach alpha for closeness, commitment, and complementarity was 0.94, 0.57, and 0.94 respectively, with an acceptable threshold set at 0.70 (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

Perceived empathy. Participants perceptions of the empathy of the coach towards the athlete depicted in each video were measured using an adapted version of Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE; Reniers et al., 2011). Normally this scale is used to measure an individual’s beliefs about their own affective and cognitive empathy abilities; in this case the questionnaire was modified to reflect an inference about the coach depicted in the videos empathy ability. Two subscales were assessed: Perspective taking; a measure of cognitive empathy that captures how well an individual understands what others are thinking and feeling (e.g., The coach can easily tell if someone else wants to enter a conversation”). Proximal responsitivity; a measure of affective empathy that captures how an individual’s emotions mirror those of others they interact with (e.g. “The coach often gets emotionally involved with his/her athletes problems”). The two subscales are made up of statements perspective taking (10) and proximal responsitivity (4). The scale range is from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). For this sample, Cronbachs alpha was 0.93, and 0.89 respectively.

Procedure

Full approval was granted by the institution’s Research Ethics Committee before commencing the study. All participants were fully briefed and completed an informed consent before progressing. Data was collected in a range of private locations with the participants being shown the videos on a laptop with headphones. Videos were presented to the participants in a random order. At the conclusion of each individual video the participants were asked to rate the coach using the two instruments (CART-Q and QCAE). After watching all four videos participants were fully debriefed.

RESULTS

The means and standard deviations for each subscale are shown in table 1 and 2 while table 3 shows the effect sizes between each pairing of videos across all variables. Each dependent variable was analysed using a 2×2 between-subjects ANOVA (coach gender/athlete gender).

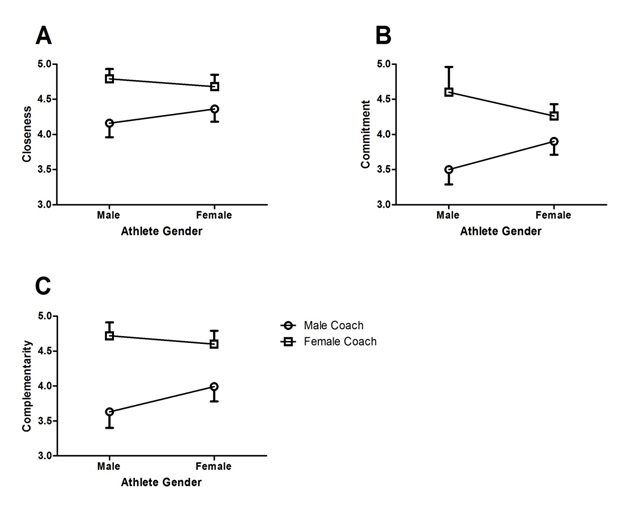

Relationship Quality (see figure 1). For closeness the analysis revealed a significant main effect for coach gender, F (1, 40) = 8.5, p < 0.05, with female coaches being perceived as displaying a greater level of closeness than male coaches (see figure 1-A). There were no other significant main effects. The results revealed that the female coach with male athlete video was scored significantly higher than the male coach with female athlete video (d=0.42) and male coach with male athlete (d=0.58). The female coach with female athlete video was significantly higher than the male coach with male athlete video (d=0.44) and with female athlete video (d=0.29). For commitment the analysis revealed a significant main effect for coach gender, F (1, 40) = 9.97, p < 0.05, with female coaches being perceived as displaying a greater level of commitment than male coaches (see figure 1-B). There were no other significant main effects. The results revealed that the female coach with male athlete video was scored significantly higher than the male coach with female athlete video (d=0.41) and male coach with male athlete (d=0.58). The female coach with female athlete video was significantly higher than the male coach with male athlete video (d=0.61) and with female athlete video (d=0.36). For complementarity the analysis revealed a significant main effect for coach gender, F (1, 40) = 14.77, p < 0.05, with female coaches being perceived as displaying a greater level of complementarity than male coaches. The results revealed that the female coach with male athlete video was scored significantly higher than the male coach with female athlete video (d=0.56) and male coach with male athlete (d=0.86). The female coach with female athlete video was significantly higher than the male coach with male athlete video (d=0.72) and with female athlete video (d=0.47). Additionally, there was a significant interaction effect, F (1, 40) = 4.32, p < 0.05, with male coaches being perceived as displaying a greater level of complementarity when working with female athletes (see figure 1-C). There were no other significant main effects. The results revealed that the male coach with male athlete video was scored significantly lower than the male coach with female athlete video (d=0.25).

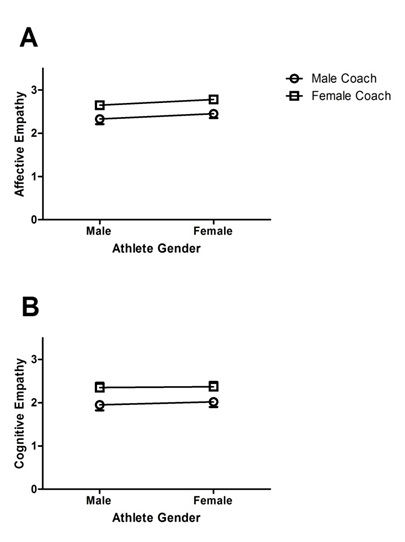

Empathy (see figure 2). For affective empathy the analysis revealed a significant main effect for coach gender, F (1, 38) = 9.4, p < 0.05, with female coaches being perceived as displaying a greater level of affective empathy than male coaches. The results revealed that the female coach with male athlete video was scored significantly higher than the male coach with female athlete video (d=0.37) and male coach with male athlete (d=0.53). The female coach with female athlete video was significantly higher than the male coach with male athlete video (d=0.70) and with female athlete video (d=0.56). Additionally, there was a main effect for athlete gender, F (1, 38) = 5.35, p < 0.05, with coaches paired with female athletes being perceived as displaying a greater level of affective empathy (see figure 2-A). The results revealed that the female coach with female athlete video was scored significantly higher than with the male athlete (d=.028). Similarly, the male coach was scored significantly higher with the female athlete than male athlete (d=0.17). There were no other significant main effects. For cognitive empathy the analysis revealed a significant main effect for coach gender, F (1, 40) = 6.4, p < 0.05, with female coaches being perceived as displaying a greater level of cognitive empathy than male coaches (see figure 2-B). The results revealed that the female coach with male athlete video was scored significantly higher than the male coach with female athlete video (d=0.45) and male coach with male athlete (d=0.53). The female coach with female athlete video was significantly higher than the male coach with male athlete video (d=0.55) and with female athlete video (d=0.47). There were no other significant main effects.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore how the gender mix of a coach-athlete dyad influences how a coach and the quality of their relationship with an athlete was perceived. It was hypothesized that gender mixes that reinforced traditional roles (e.g., male coach working with a female athlete) would be perceived as possessing greater relationship quality. Additionally, it was hypothesized that while female coaches would be perceived as having greater empathy than male coaches, this would be significantly less when the gender mix violated traditional roles (i.e., the female coach is working with a female athlete).

The results showed a significant main effect for coach gender with female coaches being rated consistently higher than male coaches across the three dimensions of relationship quality (closeness, commitment and complementarity). It should be noted that the intra-item reliability for the subscale of commitment was below a normally acceptable threshold. Therefore, the results for this subscale must be treated with caution, however these were consistent with the results for the closeness and complementarity subscales. There was also a significant interaction effect with male coaches being perceived as displaying a greater level of complementarity when working with female athletes. Additionally, while not significant, both male and female coaches were rated higher across all dimensions of relationship quality when working with an athlete of the opposite gender.

It was expected that male coaches would score highest overall when paired with female athletes. However, female coaches were rated consistently higher than male coaches regardless of the athlete gender. This may be due to the focus on relationship quality. Females have been shown to possess greater levels of emotional intelligence and transformational leadership skills (Mandell & Pherwani, 2003). This suggests that females may be seen as possessing greater social skills than males. Also females tend to be perceived as being caring, sociable and understanding whereas men tend to be seen as assertive and aggressive (Eagly & Wood, 1991). The results of this study then may be an artifice of the scenario in which the coach and athlete are discussing the athlete’s deselection. If the scenario had been of a practical coaching scenario with the emphasis placed on pragmatic leadership behaviors such as direction and organisation then is it possible the male coaches would have been rated higher in line with traditional leadership/gender stereotypes (e.g., Tomlinson & Yorganci, 1997).

While it was expected that male coaches would be rated higher when working with female athletes, a relationship that reinforces both traditional coach and gender roles (Eagly & Karau, 2002), it was not predicted that female coaches would also be rated higher when working with opposite gender athletes. Magnusen and Rhea (2009) have previously shown that male athletes tend to be more comfortable with a male coach while Blom et al (2011) reported that male athletes continually test female coaches. This again may be an artifice of the scenario that focuses on the social interaction and discussion between the coach and the athlete. In such a scenario traditional perceptions of gender interaction may be more prominent than the stereotypes of the coach and athlete roles. In same-gender groups, individuals’ behaviours are often more gender stereotyped than behavior in mixed-gender groups (Fitzpatrick, Mulac, & Dindia, 1995). For example, females in same-gender groups display greater emotion. Conversely, in mixed-gender situations, individuals adjust their behaviour to accommodate their partner (e.g., Deaux & LaFrance, 1998). It is possible that despite the dialogue and behaviours being consistent across the videos used in this study that participants were influenced by stereotypes of gender interaction and therefore perceived mixed-gender dyads to be more accommodating and effective than same-gender dyads.

In line with the widely held stereotype is that women possess a greater insight and sensitivity into the feelings of others than men (Ickes, Gesn, & Graham, 2000), results showed a significant main effect for coach gender with female coaches being rated consistently higher than male coaches in both affective and cognitive empathy. It has been argued that people as a whole believe that there is a differential ability between genders; and so women as a group possess some inherent ability/skill that makes them more empathic than men (Ickes, Gesn, & Graham, 2000). This stereotype may have caused participants to rank the female coaches higher despite the dialogue and behaviours being consistent across the videos.

Additionally, there was a significant main effect for athlete gender, with coaches, regardless of gender, being perceived as displaying a greater level of affective empathy with female athletes. Research has previously shown that female partners tend to be treated in a friendlier manner than male partners are (Guerrero, 1997). As previously, it is possible that participants were influenced by previously formed stereotypes of how different genders interact in social situations. If this is the case, they may have perceived the coaches to be friendlier and more understanding of the female athletes’ situation and therefore inferred a greater level of affective empathy.

While the results of this study offer a greater understanding of how the gender of a coach and an athlete influence how they are perceived they also highlight the importance of the context of that interaction. In this study the videos depicted a discussion about deselection taking place privately outside of the training environment. This may have created a greater emphasis on the social interaction and communication behaviors of the coach and the athlete. Had the scenario depicted a more traditional coaching environment with instruction and training it could be argued that the emphasis would have been more focused on the coaches’ knowledge, practical ability, and directive behaviors. These would have favoured the traditional gender stereotypes of males (Eagly & Wood, 1991). It is important to note that both scenarios are part of a coaches’ role (Gilbert, Cote & Mallet, 2006). It could be argued then that different aspects of the coaches’ role favour different skill sets that fall within gender stereotypes; specific scenarios requiring the coach to demonstrate social ability and understanding (traditional female traits) and in others when the coach must be assertive and directive (traditional male traits; Eagly & Wood, 1991). If this is the case, male and female coaches may be rated as more or less effective depending on the context in which they are acting. It would be useful for future research to investigate how same-sex coaches are perceived when exhibiting masculine and feminine traits.

The scenario depicted in this study was created to be sport-neutral. That is, no references are made to any specific sport or sport-type (e.g., mentioning a sport name, specific skills or equipment). While this controlled for this variable it also meant that the influence of sport-type was not explored. Different sports have a level of perceived masculinity or femininity influenced by the gender of those who traditionally participate in those sports as well as the actual activities involved in the sports (Koivula, 2001). For example, contact sports such as rugby or combat sports tend to be traditionally seen as masculine while artistic sports such as gymnastics are often seen as feminine. There may be a potential interaction of the genders of the coach and athlete with the perceived gender of the sport that influences how a coach and the quality of their relationship with an athlete are perceived. It may be where the coach gender aligns with that of the sport that they are perceived more favourable. For example, in combat or contact sports, traditionally seen as masculine sport, it may be that a coach is perceived more positively when they are assertive and directive. As these are masculine traits the coach is likely to be seen more favourable if they align with their traditional gender roles, i.e., if the coach is also male (Heilman, Wallen, Fuchs, & Tamkins, 2004). It would be useful for future research to investigate how sport-type, particularly highly masculine and feminine sports, influence how coaches.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of the present a novel methodology that highlighted that the gender of a coach and of an athlete play a key role in how their interactions are interpreted. The results highlight that female coaches are perceived more favorably than male coaches when the quality of their relationship with an athlete is judged and in terms of the levels of empathy they display. However, the discussion highlights the probable influence of the setting of the coach-athlete interaction and other contextual factors. Future research needs to address how the focus of the interaction (e.g., training, competition, administration) influences how coaches are perceived as well as exploring the potential impact of gender-association of specific sports (e.g., combat vs. artistic sports).

APPLICATIONS IN SPORT

These findings have implications for coaching practice as a coaches’ gender has an effect on how they are perceived, in particular female coaches may be perceived more favorably than male coaches by athletes when dealing with emotional situations. The results also demonstrate that mixed-gender partnerships tend to be perceived more favorably than same-gender partnerships. Male and female coaches need to be aware of how their gender effects athletes’ perceptions of them. In the study female coaches were rated higher in terms of relationship quality and empathy despite the same script, facial expression, body language and position being kept consistent between the videos of the male and female coach. This shows that male coaches in emotional coaching situations need to be aware of how athletes perceive them in relation to their gender, an awareness of this would allow them to attempt to alter their behaviour.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None

REFERENCES

1. Augoustinos, M. & Walker, I. (1995). Social cognition: An integrated introduction. London: Sage Publications.

2. Becker, A. J. 2009. It’s not what they do, It’s how they do it: Athlete experiences of great coaching. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 4 (1), 93-119.

3. Blom, L. C., Abrell, L., Wilson, M. J., Lape, J., Halbrook, M., & Judge, L. W. (2011). Working with male athletes: the experiences of U.S. female head coaches. Journal of Research in Health, Physical Education, Recreation, Sport and Dance, 6(1), 54-61.

4. Burke, M. (2001). Obeying until it hurts: Coach-athlete relationships. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 28, 227-240.

5. Deaux, K. & LaFrance, M. (1998). Gender. In D. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 788-827). New York: Random House.

6. Eagly. A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002) Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573-598.

7. Eagly, A. H., & Wood, F. W. (1991). Explaining sex differences in social behavior. A meta – analytic perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 306-315.

8. Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2004). Implicit leadership theories in applied settings: Factor structure, generalizability, and stability over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 293-310.

9. Fiske, S. T., & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum model of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influence of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 23, pp. 1-74). New York: Academic Press.

10. Fitzpatrick, M. A., Mulac, A., & Dindia, K. (1995). Gender-preferential language use in spouse and stranger interaction. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 14, 18-3.

11. Gawronski, B. (2003). On difficult questions and evident answers: Dispositional inference from role-constrained behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1459-1475.

12. Gilbert, W., Cote, J., & Mallett, C. (2006). Developmental Paths and Activities of Successful Sport Coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 1(1), 69-76.

13. Guerrero, L. K. (1997). Nonverbal involvement across interactions with same-sex friends, opposite-sex friends and romantic partners: Consistency or change? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14, 31-54.

14. Heilman, M. E., Wallen, A. S., Fuchs, D. & Tamkins, M. M. (2004). Penalties for success: Reactions to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 416-427.

15. Ickes, W., Gesn, P. R., & Graham, T. (2000). Gender differences in empathic accuracy: Differential ability or differential motivation? Personal Relationships, 7, 95-109.

16. Jowett, S., & Ntoumanis, N. (2004). The Coach-Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART – Q): Development and initial validation. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 14, 245–257.

17. Kamphoff, C. (2010). Bargaining with patriarchy: former women coaches experiences and their decision to leave collegiate coaching. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 81, 367-379.

18. Koivula, N. (2001). Perceived characteristics of sports categorized as gender-neutral, feminine and masculine. Journal of sport behaviour. 24, 377-393.

19. Lorimer, R., & Jowett, S. (2010). The influence of role and gender in the empathic accuracy of coaches and athletes. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 11, 206-211.

20. Lyle, J. (2002). Sports coaching concepts. London, UK: Routledge.

21. Mandell, B. & Pherwani, S. (2003). Relationship between emotional intelligence and TL style: A gender comparison. Journal of Business & Psychology, 17(3), 387-404.

22. Manley, A. J., Greenlees, I., Graydon, J., Thelwell, R., Filby, W.C.D., & Smith, M.J. (2010). Athletes’ Perceptions of the Sources of Information Used When Forming Initial Impressions and Expectancies of a Coach. The Sport Psychologist, 22, 73-89.

23. Magnusen M. J. & Rhea D. J. (2009). Division I athletes attitudes toward and preferences for male and female strength and condition coaches. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23(4): 1084-1090.

24. Reniers R. L, Corcoran R, Drake R, Shryane N. M, & Völlm B. A. (2011). The QCAE: A Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 84–95.

25. Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Nauts, S. (2011). Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 165-179.

26. Tavakol, M. & Dennick, R. 2011. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education. 2, 53-55.

27. Tomlinson, A., & Yorganci, I. (1997). Male coach/female athlete relations: Gender and power relations in competitive sport. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 21, 134-155.

28. Wood, W., & Eagly, A. H. (2012). Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. In M. P. Zanna & J. M. Olson (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

29. Wylleman, P. (2000). Interpersonal relationships in sport: Uncharted territory in sport psychology research. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 31, 555-572.