Authors: Kevin Smith1, Con Burns1, Cian O’Neill1, Nick Winkelman2, Matthew Wilkie2, Edward K. Coughlan1

1Department of Sport, Leisure & Childhood Studies, Munster Technological University, Cork, Ireland

2Irish Rugby Football Union, 10 Lansdowne Rd, Dublin 4, Ireland

Corresponding Author:

Kevin Smith

Department of Sport, Leisure & Childhood Studies, Munster Technological University, Cork, Ireland

+353 85 73 29 326

Kevin Smith is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sport, Leisure & Childhood Studies at Munster Technological University, Cork, Ireland. His area of research focuses on the evaluation of a coach education framework in school and club settings in rugby union.

Dr. Con Burns is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Sport, Leisure and Childhood Studies at Munster Technological University, Cork, Ireland. His areas of research include coaching science, sport science and physical activity promotion.

Dr. Cian O’Neill is Head of the Department of Sport, Leisure & Childhood Studies at Munster Technological University, Cork, Ireland. His areas of research include coaching science, sports performance analysis, human performance evaluation and the broad sports science domain.

Dr. Nick Winkelman is the head of athletic performance & science for the Irish Rugby Football Union. His primary role is to oversee the delivery and development of strength & conditioning and sports science across all national (Men and Women) and provincial teams (Leinster, Munster, Connacht, and Ulster).

Matthew Wilkie is the national high performance coach development manager for Rugby Australia. He previously worked as the head of coach development for the Irish Rugby Football Union.

Dr. Edward K. Coughlan is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Sport, Leisure & Childhood Studies at Munster Technological University, Cork, Ireland. His areas of research include skill acquisition, practice-transfer, deliberate practice, sport science and coaching science.

COVID-19 Challenges and Associated Impact on the Design of a Coach Education Research Study in Rugby Union: A Research Report

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic posed challenges to many conventional aspects of sport and research with government lockdowns, social-distancing and sanitisation protocols significantly impacting everyday life. The purpose of this report is to outline how a coach education research study in rugby union was adapted, methodologically and procedurally, in response to government health guidelines due to COVID-19, while striving to stay true to the original research design. This design sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a coach education intervention in a practical setting by recording and examining coach’s (n = 5) behaviours, inclusive of their perceptions of relationships with the athletes (n = 68) they coach, and vice-versa, pre- and post-intervention. Prior to lockdown, participants had completed the pre-intervention phase and education intervention, leaving the post-intervention observation phase incomplete. To ensure study completion, this phase transferred online to comply with health regulations. Coaches received video footage and behavioural data from their previously recorded sessions as a surrogate for the planned live observations and were instructed to self-assess their performance using a bespoke mobile application designed by the research team. Numerous challenges were faced in continuing the research study, however, the technology-based methodological adaptations highlighted could provide future researchers with agile solutions, should similar unforeseen pandemic-type restrictions return.

Key Words: Health & Safety, Coaching Intervention, Coaching Framework, Coach-Athlete Relationship.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to widespread disruption to all facets of society on a global scale. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO) at the time of completion of this report, the virus has infected more than 515 million people and claimed the lives of over 6.2 million worldwide (27). The ‘new norm’ is a term frequently used to describe many of the health and safety measures imposed on the general public at local, national and international level in an effort to reduce the spread of the virus (28). The restriction of people’s movements, travel-distance limits, protective face coverings, social distancing, and strict personal sanitisation protocols are just some of the measures that became common place in response to the pandemic (11). Sports science research, and in particular the coach education domain, has required significant adaptation and innovation from researchers and coach educators to provide agile solutions in order to continue functioning effectively and safely during such unprecedented times.

The original purpose of the current research study was to investigate the effectiveness of a coach education framework (CEF) on the behaviours of coaches in an applied rugby union setting. This research process was interrupted prior to completion due to a government mandated lockdown, and subsequently required substantial procedural modifications to comply with various health restrictions, while concurrently maintaining the integrity of the research. The aim of this report is to present the obligated methodological and procedural modifications used that facilitated the continuation of the research, thereby providing coaching scientists with context-specific recommendations for future research. It is now understood that COVID-19 and its many variants may be a challenge for some years to come, and this report provides recommendations and practical solutions with regard to pivoting coaching science research in spite of pandemic regulations.

The Original Study

How a coach learns and develops as a practitioner can be described as a complex non-linear process (26). McCullick et al. (19) conducted an analysis of coach education research and concluded that CEFs were grossly underrepresented in the scientific literature, and even in the available research, there were limited quantitative data-based studies, thus making it difficult to draw more objective generalisable conclusions. This substantiates the findings of previous research that highlighted limited collaboration between skilled researchers and formal CEFs, in addition to evidence of deficits in assessing the effectiveness of said CEFs through interaction with participant alumnae (9, 19). Little has changed today as many of these shortcomings within the coach education domain still permeate the current coaching landscape (25).

Aside from empirically justified content for a CEF, the delivery medium for the recipient cohort requires careful consideration. Maclean and Lorimer (18) highlighted that coaches from multi-sport settings found informal learning (i.e. interaction with others and ‘learning by doing’) was the coaches’ preferred method to develop their craft. The same coaching cohort also supported the need for participation in coach education to be a mandatory process for any prospective coach regardless of the sport. A systematic review of coach development programmes concluded that education workshops are an effective method of disseminating coach education content as they can accurately reflect the interpersonal practical nature of coaching (17). It is here the ‘how’ of the coaching process can be addressed as opposed to simply supplying new coaching content/methods that are devoid of any contextual applications for practitioners (8). Summarising the deficit of present-day coach education processes, any CEF should be (i) empirically valid, (ii) applicable to positively impact coach behaviour, and (iii) capable of being objectively assessed (25).

The original research design in the current study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a novel CEF on coach behaviour in an applied practice setting, in this case rugby union. This CEF comprises three principle theoretical constructs applied to coaching: Self-Determination Theory (SDT), Explicit Learning Theories (ELT), and Implicit Learning Theories (ILT). SDT is a meta-theory that provides a broad framework for the study of motivation and well-being (7). ELT focus on verbal knowledge of performance that involve cognitive stages in the learning process and are reliant on working memory engagement (15), with verbal instruction, cues, and feedback the primary types of performance-related communication used by a coach (1). ILT relate to learning that occurs through practice that accentuates task involvement and reduces explicit information (20). The CEF under review in the current study aims to support a coaches’ ability to construct purposeful, game/player-centred practices that challenge the athletes to develop core sporting skills and game-understanding in an engaging learning environment. The purpose of the current research report is to (i) outline how the original study was adapted, methodologically and procedurally, in response to government and public health guidelines due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and (ii) to investigate the effect that these modifications had on the participant cohort’s coach education experience.

METHODS

Original Experimental Design

A mixed methods assessment approach was adopted to evaluate the effectiveness of the novel CEF, with coaches’ objective behaviours analysed in conjunction with perceptions of their relationship with their athletes and the athletes’ perceptions of their coaches. Coaches (n = 5) and athletes (n = 68) from two separate amateur rugby union teams were purposefully sampled. Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the Host Institution’s Research Ethics Committee.

Procedure

Coach Behaviour

The coaches’ behaviours during their practice sessions were analysed using the Coach Analysis and Intervention System (CAIS) tool (5). Coaches wore a lapel microphone (Sennheiser ME 2-II EW-Series) that was synchronised with their respective video camera (Sony Handycam 4.0 Series) to provide clear audio of their speech during their practice session. The video of each session was then coded retrospectively using the CAIS tool via the SportsCodeTM software package (Agile Sports Technologies, USA).

Questionnaires

Coach self-perceptions of their relationship with their athletes were measured using the Coach–Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART-Q) (13). Athletes from both teams completed the Coaching Behaviour Scale for Sport (CBS-S) questionnaire (16), which examined their perceptions of their coaches’ behaviours in both training and competition environments.

Intervention: Coach Education Framework Workshop

The CEF intervention was delivered via a formal facilitated workshop on location at one of the participant clubs. The workshop was delivered by a selection of experienced Coach Education staff from the proposing national governing sports body, via three separate modules, each of four hours duration across a single weekend (Saturday and Sunday). Each module focused on one of the three principle components of the framework as its central theme (SDT/ ELT/ILT). Coaches were provided with an evidence-based foundation of each component, supported by practical examples on how to apply them. The workshop was both interactive and dynamic in nature, providing the attending cohort with multiple opportunities to debate and discuss the thematic areas, whilst also drawing on every attendee’s individual coaching experiences.

Post-CEF Intervention

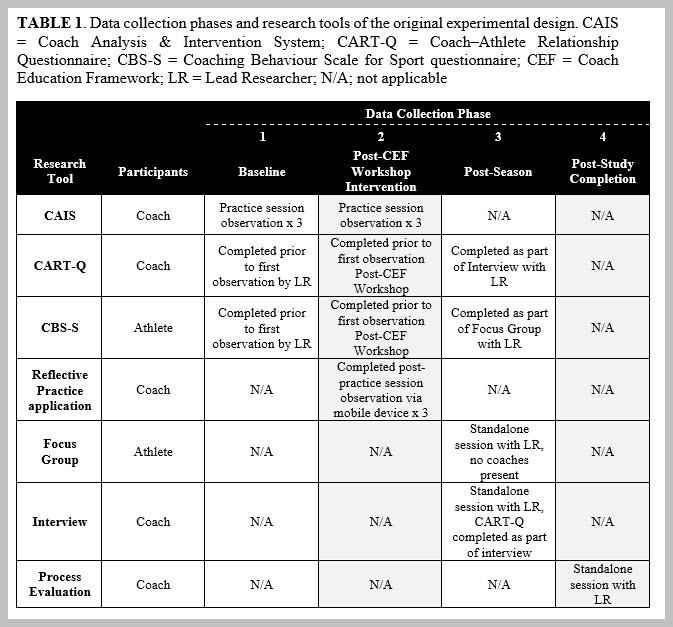

After completion of the CEF workshop, at each subsequent practice observation session coaches were to complete a post-session reflective practice exercise. The reflective exercise was to be completed immediately upon conclusion of the practice session using a bespoke application via their own personal electronic device. The reflective practice exercise was designed to be completed by coaches in less than five minutes. The exercise consisted of five questions using a 5-point Likert scale and four open-ended questions designed to elicit reflective thoughts from the coach on the aspects of their practice that they perceived as being executed well and those needing further improvement. More context-laden data was to be secured at the conclusion of the regular season via individual interviews between each coach and the lead researcher. A focus group discussion with the athletes was also planned by the lead researcher for the same purpose as the coach interviews. Upon completion of all the study’s requirements, a process evaluation was planned with all participant coaches. Table 1 presents an outline of the data collection phases of the original research plan.

RESULTS

Modifications to the Original Experimental Design in Response to Covid-19

The original research plan was thrown into disarray in March 2020 when the government mandated a public ‘lockdown’ on health and safety grounds where, among other restrictions, all sporting activity in the country was suspended indefinitely. This necessitated a re-organisation of the original research design, as it was no longer feasible to collect all of the planned post-CEF intervention data. All coaches had completed their baseline observation practice sessions, respective questionnaires and the CEF intervention workshop itself. However, no post-intervention observation had taken place by the research team at this point in time. This excluded the use of CAIS, CART-Q and CBS-S data as viable options for any post-CEF intervention evaluation of the coaches’ behaviour, coaches’ perceived relationships, and athletes’ perceptions respectively.

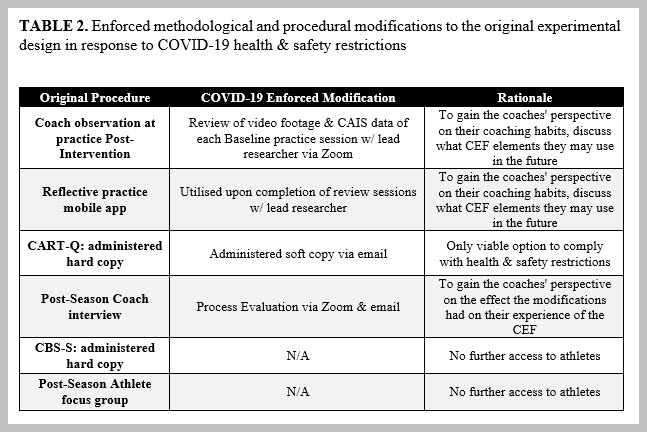

All communication and interaction from the research team with the coaches transitioned to an online platform as it was the only viable option that complied with the newly imposed public health requirements. Procedural modifications are usually implemented with the intention of retaining the original fidelity of the research intervention in question (22). Saunders et al. (21) also suggested the importance of intervention dose (the number of interactions with the research team) to participants as a central factor in any modification. It is worth noting that although the interaction medium shifted from in-person to online between coaches and researchers, the interaction dose between the two was not altered from the original study. Finally, when making modifications to an intervention in a specific context, both format (the medium of the intervention delivery, e.g. education workshop) and setting (the environment of the intervention delivery, e.g. club practice session) require careful consideration (22). The obligated modifications to the study are presented in Table 2 and were made with the aim of preserving as much fidelity, dose, and context of the original research plan as possible.

DISCUSSION

Implications of Modifications & Recommendations for Future Research

The implications of the procedural modifications altered the initial experimental design and subsequent data collection time frames of the original study without altering the aims or objectives of the research. Some researchers have already published findings regarding potential response frameworks to COVID-19 restrictions in both sport science laboratory research (12), as well as practical coaching settings (14). Although the following sections discuss recommendations as a checklist of possible alternate options for coaching educators, practitioners and researchers for the current COVID-19 pandemic, they may also have some application should similar unforeseen restrictions return in the future.

Alternate Online Options

As all interactions between coaches and the research team shifted to an online platform, most notable was the modification concerning coach practice sessions. In lieu of the planned observation of the coaches’ behaviour during a practice session, the lead researcher conducted online open-ended interviews (n = 3) with each individual coach via the teleconferencing software Zoom (San Jose, USA). In advance of these interviews, all coaches were emailed both the raw video footage of each of their previously recorded practice sessions (n = 3) and the objective CAIS data pertaining to their behaviours exhibited in each of those sessions. Each interview corresponded directly with one practice session, thus each coach completed three interviews in total. All interviews lasted between 50-60 minutes, with the lead researcher encouraging the coach to engage with a detailed discussion surrounding the rationale of their session content and subsequent execution. Coaches were encouraged to reflect upon how they would apply knowledge from the CEF into their execution of future sessions based on what they had learned and observed from reviewing their video footage. The combined use of video and objective data was used to aid coaches to develop their inner self-critic by raising their self-awareness of their own mannerisms, habits, and current practices, both positive and negative (23). All coaches noted the video footage provided an increase in their self-perceived awareness of their behaviours and how it could be a useful learning tool in the future. From a practicality standpoint for future researchers who wish to use a similar methodology, the data collection time frame post-CEF intervention increased two-fold (from 6-weeks to 12-weeks) due to an increase in preparation labour required to conduct individual data collection sessions with coaches online, as opposed to simply observing multiple participants simultaneously at a single practice session.

Interestingly, the coaches also willingly shared their own individual video footage with their fellow peers in order to critically assess and learn from one another. The coaches used this shared process as an opportunity to corroborate the so called ‘strong’ areas of their practice sessions as well as seeking constructive critical feedback on aspects that they felt warranted improvement. All participating coaches were exposed to the same research process of evaluation with regard to their behaviours and perceptions, which may have contributed to this request of feedback from their contemporaries. These organic peer-assessment pods were not included in the original research plan, yet were a strong indicator of the participants’ willingness to continually engage in an ever-evolving research project. Building upon this for the future implementation of the CEF, but also as a fall back strategy for other unprecedented events, it is recommended that coaches are given access to a media-integrated video library of coaching-in-action footage of themselves (if available) or indeed others. This could serve as a viable alternate option to facilitate a coach’s learning outside of a traditional practical setting, in a self-relevant context that ensures convenience and accessibility, regardless of their schedule. Technology-enhanced learning (TEL) is a term used to describe the growing utilisation of digital mediums to aid learning in a coaching/teaching context (6). FlipGridTM is one such example of a multi-media communication TEL tool that integrates a coach’s ability to review video footage and add feedback embedded to the content in either verbal or written form (24). This tool also allows for multiple participants to engage over a single video thus streamlining the process away from multiple one to one interactions like the peer-assessment pods formed by the coaches in this study. However, the ethical and appropriate use of video footage is a potential obstacle that could work against widespread dissemination and is certainly something practitioners need to be explicitly aware of (4).

Reflective Practice

At the conclusion of the video interview review session (n = 3 per coach), each coach completed the reflective practice post-session exercise via the bespoke application as detailed in the previous section. This served as a direct surrogate for the planned reflective practice exercise that the coaches would have completed post-practice session, if the restrictions permitted session-observation by the research team. While all of the coaches acknowledged the utility and benefit that the reflective exercise had in improving their session planning, particularly as they were using their own video footage, they highlighted the limitation of not having an opportunity to action these new learnings in practice environments due to restrictions. The coaches did note the ease of completing the reflection exercise was influenced directly by the convenience of completing it at their leisure on a mobile device. Acting as an adjunct to the previous recommendation for coaches to have access to a video library as a learning resource, it is recommended that coaches have access to a user-friendly application for the purpose of completing reflective practice post-session, be it a video or a practical session review.

Questionnaires

All coaches completed their CART-Q questionnaires at the originally specified time points, albeit via an online digital platform as opposed to in-person with a hard copy. The coaches highlighted no objections or adverse experiences to the new online arrangement, simply citing it as necessary modification given the enforced restrictions. Future research may explore the reduction of in-person contact with participants for health and safety reasons by shifting all ‘soft-copy’ suitable data collection (e.g. questionnaires) to an appropriate online medium.

Process Evaluation

All coaches completed the process evaluation interview via Zoom and questionnaire via email correspondence. A process evaluation could be described metaphorically as ‘the black box’ of how the implementation of a certain programme worked in practice, detailing as comprehensively as possibly the various intervention components relationships (2). This was conducted to gain an insight into participant perceptions of the modifications used and their resultant learning experiences, with all noting the negative effect COVID-19 had on the implementation of the research project. All of the coaches highlighted their satisfaction with the process as a whole (modifications included), but acknowledged that the effectiveness of the CEF was difficult to ascertain as they had no opportunity to apply any of their learnings in practice with their athletes. These coach musings relating to how their habits could be affected by participation in the CEF substantiate wider concern in the research community as the evidence highlighting the effectiveness of formal coach education on changing a practitioner’s behaviour positively is limited at best (3). Consequently, it would be inappropriate to extrapolate the coaches’ self-perceived learning as actual observable learning through behaviour change. However, it could be argued that a change in one’s knowledge could act as a precursor to a change in subsequent behaviour, with raising the coach’s self-awareness of their coaching habits (23), perhaps initiating these behavioural shifts. Similar to questionnaire data collection methods, it is recommended that should it be necessary to minimise person-to-person contact for health and safety reasons in future research, that a process evaluation could be completed through an appropriate online medium.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic caused much disruption to sport and coaching science research and forced practitioners to be adaptable to new health and social restrictions. This paper details how (i) the original study was adapted, methodologically and procedurally, in response to government and public health guidelines due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and (ii) the effect that these modifications had on the participant cohort’s coach education experience. The obligated modifications to the study were made with the aim of preserving as much fidelity, dose, and context of the original research plan as possible, with technology-based modifications providing future researchers and coaches with possible solutions, should similar unforeseen restrictions return.

APPLICATIONS TO SPORT

The use of surrogate video footage, TEL opportunities as coach learning tools, and alternate online data collection procedures are just some of the potential solutions available to coaches and coaching science researchers if faced with future pandemic health and social restrictions. Moreover, while these modifications were received positively by each coach, the strength of the changes were shown in the continuation of the data collection process and subsequent evaluation of the original concepts in spite of government restrictions. Coach education research needs to build on the current literature and find a tangible connection for coaches to best utilise the marriage of policy, education, and practice for coaches and athletes alike (8, 10). The original research plan, along with context appropriate modifications highlighted in this work, could provide future practitioners with agile solutions to continue coaching science research should pandemic-type restrictions make a return in the future.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Benz, A., Winkelman, N., Porter, J.M. & Nimphius, S. (2016). Coaching instruction and cues for enhancing sprint performance. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 38, 1, 1-11, doi: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000185.

- Bouffard, J. A., Taxman, F. S., & Silverman, R. (2003). Improving process evaluations of correctional programs by using a comprehensive evaluation methodology. Evaluation and Program Planning, 26(2), 149-161, doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00010-7.

- Cope, E., Cushion, C.J., Harvey, S. & Partington, M. (2020). Investigating the impact of a Freirean informed coach education programme. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, doi: 10.1080/17408989.2020.1800619.

- Cope, E., Partington, M., & Harvey, S. (2016). A review of the use of a systematic observation method in coaching research between 1997 and 2016. Journal of Sports Sciences, doi: 10.1080/02640414.2016.1252463.

- Cushion, C.J., Harvey, S., Muir, B & Nelson, L (2012). Developing the Coach Analysis and Intervention System (CAIS): Establishing validity and reliability of a computerised systematic observation instrument. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30, 2, 201-216, doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.635310.

- Cushion, C.J & Townsend, R.C. (2018). Technology enhanced learning in coaching: a review of literature. Educational Review, 71:5, 631-649, doi: 10.1080/00131911.2018.1457010.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268, doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

- Dempsey, N.M., Richardson, D.J., Cope, E., & Cronin, C.J. (2020). Creating and disseminating coach education policy: a case of formal coach education in grassroots football. Sport, Education and Society, 26:8, 917-930, doi: 10.1080/13573322.2020.1802711.

- Gilbert, W., Gaillimore, R. & Trudel (2009). A learning community approach to coach development in youth sport. Journal of Coach Education, 2(2), 3-23, doi: 10.1123/jce.2.2.3.

- Griffo, J.M., Jensen, M., Antony, C.C., Baghurst, T., & Hodges Kulinna, P. (2019). A decade of research literature in sport coaching (2005-2015). International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(2), 205-215, doi: 10.1177/1747954118825058.

- Health Service Executive. (2021). Protect Yourself and Others from COVID-19. Retrieved 03/04/2021 from: https://www2.hse.ie/conditions/coronavirus/protect-yourself-and-others.html

- Jermyn, S., O’Neill, C., & Coughlan, E.K. (2021). The impact and implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on the design of a laboratory-based coaching science experimental study: A research report. The Sport Journal. Online version. Retrieved from https://thesportjournal.org/article/the-impact-and-implications-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-the-design-of-a-laboratory-based-coaching-science-experimental-study-a-research-report/.

- Jowett, S. & Ntoumanis, N. (2004). The Coach-Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART-Q): Development and initial validation. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sport, 14, 245-257, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2003.00338.x.

- Kelly, A.L., Erickson, K., & Turnnidge, J. (2020). Youth sport in the time of COVID-19: Considerations for researchers and practitioners. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27:1-2, 62-72, doi: 10.1080/23750472.2020.1788975.

- Kleynen, M., Braun, S.M., Bleijlevens, M.H., Lexis, M.A., Rasquin, S.M., Halfens, J., Wilson, M.R., Beurskens, A.J., & Masters, R.S. (2014). Using a Delphi technique to seek consensus regarding definitions, descriptions and classifications of terms related to implicit and explicit forms of motor learning. PLoS One, 9(6): e100227, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100227.

- Koh, K. T., Mallett, C., & Wang, C. K. J. (2009). Examining the ecological validity of the Coaching Behavior Scale (Sports) for basketball. International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 4(2), 261–272, doi: 10.1260/174795409788549508.

- Lefebvre, J.S., Evans, M.B., Turnnidge, J., Gainforth, H.L., & Côté, J. (2016). Describing and classifying coach development programmes: A synthesis of empirical research and applied practice. Journal of Sports Sciences & Coaching, 11, 887-899, doi: 10.1177/1747954116676116.

- Maclean, J. & Lorimer, R. (2016). Are coach education programmes the most effective method for coach development? International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10 (2), 71-88, http://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/ArticleDetail/NODE07227554

- McCullick, B., Schempp, P., Mason, I., Foo, C., Vickers, B. & Connolly, G. (2009). A scrutiny of the coaching education program scholarship since 1995. Quest, 61, 322-335, doi: 10.1080/00336297.2009.10483619.

- Renshaw, I. & Moy, B. (2018). A Constraint-Led Approach to coaching and teaching games: Can going back to the future solve the ‘they need the basics before they can play a game’ argument? Ágora para la Educación Física y el Deporte, 20, 1, 1-26, doi: 10.24197/aefd.1.2018.1-26.

- Saunders, R.P., Evans, M.H., & Joshi, P. (2005). Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to-guide. Health Promotion Practice, Vol. 6, No. 2, 134-147, doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387.

- Stirman, S.W., Miller, C.J., Toder, K., & Calloway, A. (2013). Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 2013, 8:65, doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-65.

- Stodter, A. & Cushion, C. (2019). Evidencing the impact of coaches’ learning: Changes in coaching knowledge and practice over time. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37:18, 2086-2093, doi: 10.1080/02640414.2019.1621045.

- Stoszkowski, J., Hodgkinson, A. & Collins, D. (2020). Using Flipgrid to improve reflection: a collaborative online approach to coach development. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26:2, 167-178, doi: 10.1080/17408989.2020.1789575

- Turnnidge, J., & Côté, J. (2017). Transformational coaching workshop: applying a person-centred approach to coach development programs. International Sport Coaching Journal, 4, 314-325, doi: 10.1123/iscj.2017-0046

- Trudel, P., & Gilbert, W. (2006). Coaching and coach education. In Kirk, D., O’Sullivan, M., & McDonald, D. (Eds.) Handbook of Physical Education, 516-539, London: Sage.

- World Health Organisation. (2022). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved 21/04/2022 from https://covid19.who.int/

- World Health Organisation. (2021). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. Retrieved 03/04/2021 from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public