Authors: Adem Solakumur1, Ahmet, N. Dilek2, Yilmaz Unlu3 and Murat Kul4

1Department of Sports Physical Education, Faculty of Sport Sciences, The University of Bolu Abant İzzet Baysal, Bolu, Turkey

2Department of Sports Recreation, Faculty of Sport Sciences, The University of Bartin, Bartin, Turkey

3Department of Physical Education, Faculty of Sport Sciences, The University of Bartin, Bartin, Turkey

4Department of Sports Management, Faculty of Sport Sciences, The University of Bayburt, Bayburt, Turkey

Corresponding Author:

Adem Solakumur, Ph.D

Department of Physical Education, School of Physical Education and Sports,

University of Abant Izzet Baysal, Golkoy Kampusu, 14030, Bolu/TURKEY

orcid.org/0000-0001-8377-7912

Office Phone: +903742534571

mobile phone: +90 505 933 1502

Fax: +90 374 2534636

Email: adem.solakumur@ibu.edu.tr

(1) Adem Solakumur, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Department of Physical Education at the University of Abant Izzet Baysal, His research interests focus on sports management and psycho-social issues.

(2) Ahmet Naci Dilek, Ph.D., is a researcher in the field of social relations and recreational activities.

(3)Yılmaz Ünlü, Ph.D., is a researcher in the field of Social Relations and Sport Management.

(4) Murat Kul is associate professor in Sports Management and Physical Education at the Bayburt University.

The Effect of Coaches’ Leadership Behaviors on Athletes’ Emotion Regulation Strategies

Abstract

Purpose: There are various studies that show that the attitudes and behaviours of sports stakeholders (e.g., coaches, supporters, managers, etc.) have positive and negative consequences on the emotion regulation strategies of athletes. In these studies, there is not enough evidence to reveal the effect of the leadership behaviors of the coaches who interact and direct the athlete, who is the subject of the sport, Specifically, there is not enough evidence to indicate the impact of leadership behaviors on the emotional states of the athletes. Therefore, this research examines the effect of four dimensions of coaches’ leadership behaviors (e.g., educational and supportive, democratic, explanatory and rewarding, and autocratic) on athletes’ emotional regulation strategies (e.g., suppression and cognitive reappraisal).

Theoretical background: The research is supported by the theory of “Multidimensional Sports Leadership.”

Methods: In order to collect data in the research, the “Leadership Scale for Sports” and “Emotion Regulation Scale” were used together with a personal information form. Correlation and multiple regression analysis were applied to determine the relationships between variables. The data were obtained from a total of 378 athletes including 168 women and 210 men. A survey was used as part of a field study on participating athletes.

Findings: “Autocratic” leadership behaviors of the coaches positively predicted the “Suppression” strategy of the athletes. Additionally, explanatory and autocratic leadership behaviors of coaches predict the “Cognitive Reappraisal ” strategy of the athletes in a positive way. “Autocratic” leadership behaviors of coaches positively predicted the “Suppression” strategy of the athletes. Additionally, “Explanatory and Autocratic” leadership behaviors of coaches predict the “Cognitive Reappraisal ” strategy of the athletes in a positive way.

Results: Trainers, by considering how leadership behaviors can positively affect the emotion regulation strategies of the athletes can create a healthy sports environment that will support sportive performance and success.

Keywords: Suppression, Cognitive Reappraisal, leadership

Introduction

Today, besides its individual effects, sport is a social institution that significantly influences, directs, and builds social dynamics and has a strong organizational structure. This social institution has a wide sports circle that includes many individuals, institutions, and organizations represented by athletes, fans, managers, trainers, material suppliers, owners, legal committees, etc.

There are interactions at various levels between these stakeholders who make up the environment of sports that on prioritizes the athletes. It is argued that the interaction between the coaches and athletes as well as among the many stakeholders of the sporting environment, has various effects on the sportive performance and success of the athlete (15, 19, 38, 40, 43,47).

In addition to the athletic abilities and field knowledge of trainers, human relations and leadership characteristics also play a critical role in their interactions with athletes (10, 34). A coach with effective leadership behavior should be able to see the multi-factor structures that affect the success and performance of the athlete while also guiding the athlete in a timely manner and enabling him or her to deal with difficulties and problems effectively. The coach should cooperate with the family and other stakeholders to manage the various emotions experienced by the athlete during the sports processes. In addition to that expectation and knowing the psycho-social characteristics of the athlete, the coach should create the right approach and communication channels to correctly direct the emotional fluctuations, excitement levels, and anxiety of the athlete (4, 42). To cope with these complex tasks, coaches must identify the needs of the athletes, understand their motivational styles, and use appropriate strategies in a conducive, honest, and collaborative environment. For this reason, coaches should exhibit leadership behaviors appropriate to the process and have the right leadership knowledge and attitude toward various personal and environmental situations (58).

Relationship between leadership behaviors and emotion regulation strategies

According to the leader-member exchange theory, leadership is an emotional and social interaction process that focuses on interactions between leaders and subordinates (21). Leadership, the principle of which is to arouse emotion in followers (14), is a process in which everything a leader says or does affects his followers (59). The “Multidimensional Sport Leadership Model” also attributes the effectiveness of the leader in sports to the harmonious interaction between the leader and the situational characteristics of the group members (12). Leaders are those who can manage their own emotions as well as manage the emotional states of others effectively (29, 44). These approaches show that leadership depends on effective leader-member interaction by addressing the positive and negative relationships that leaders have with their followers (45). The healthy communication that the coaches will establish with the athletes in the sportive process is of great importance as it affects the attempts of the athletes to regulate their emotions (6,52).

If a coach’s leadership behavior is consistent with the athletes’ perceptions of their coach (for example, preferred, necessary, and real), positive sports performance and satisfaction are likely to occur (36). This situation affects the emotions and performance of the athletes, revealing cognitive, motivational, and physical results (34). The inability of an athlete with a high level of anxiety to perform at an optimum level indicates the effect of emotions on the sportive process (56). A mistake made during the competition, a lost or won point, and interactions with teammates, coaches, or spectators can cause rapid emotional transitions in athletes.

Emotion regulation refers to the process of which emotions individuals have, and when and how they experience these emotions (22). Individuals generally reduce negative emotional experiences and increase positive emotions with regulation techniques (33). In other words, an individual’s ability to cope with negative emotions and reduce the negative consequences of these emotions is achieved through the emotion regulation process (7, 13, 28, 55). Emotion regulation strategy has two sub-dimensions including “cognitive reappraisal and suppression.” Cognitive emotion regulation is the ability to control, evaluate, and find solutions to problematic emotions through cognitive processes (37) cognitive responses to emotional stimuli (1), and through cognitive coping ability (18).

Another regulation strategy is “suppression” which is to prevent the expression of emotions. Suppression, which is one of the response-oriented emotion regulation strategies, is about reducing or changing the emotion after the emotion occurs. A person either hides or reduces his/her positive and negative feelings while struggling with the difficulties he/she experiences, or he/she reacts to these feelings at a lower level (31). Frequent use of the suppression strategy causes the person to feel bad, have negative emotions and depression, weaken their social interaction, cause a negative reaction to the interacted environment, and cool down interpersonal relationships (20, 31).

Emotion regulation is a key competence associated with effective and good leadership. Leaders who use the emotion regulation process effectively on themselves and their subordinates contribute more to organizational efficiency by being more successful in communication (8, 28, 32, 55). Emotional images of trainers (2), emotional content of conversations (57), and emotional intelligence (53) affect the emotion regulation strategies of athletes.

When the literature is examined, it is seen that studies on emotion regulation in sports focus on athletes’ emotional expressions, their emotion regulation strategies, and health and performance (27, 39). Various studies involving a coach, supporter, manager, etc. show that the attitudes and behaviors of sports stakeholders have positive and negative consequences on the emotion regulation strategies of athletes. In these studies, there is not enough evidence to reveal the effect of the leadership behaviors of the coaches who interact with and direct the athlete. Nor does evidence indicate the impact of the leader behavior on the emotional states of athletes. Therefore, this research examines the effect of coaches’ leadership behaviors (e.g., educational and supportive, democratic, explanatory and rewarding, or autocratic) on the emotional regulation strategies of athletes (e.g., suppression and Cognitive reappraisal).

It is thought that the results of the research will guide sports managers, trainers, and those working in the field to better serve athletes.

Research Design

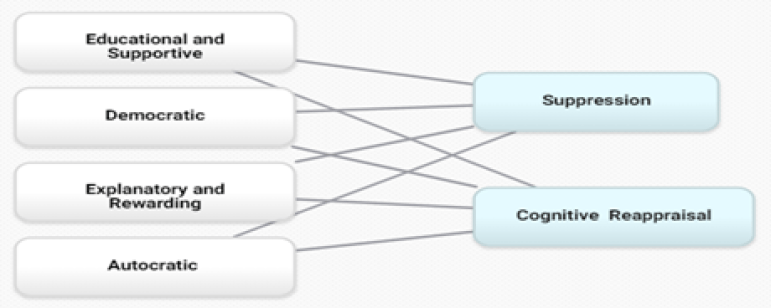

In this study, the collection and analysis of the data were made using quantitative methods Survey method was applied to obtain primary data in the empirical study. The survey model was used to obtain primary data which was conducted as a field study. The conceptual model of the research is presented in Figure 1.

The following hypotheses have been proposed for this model.

H1a: Coaches’ educative and supportive leadership style has an impact on suppression strategy.

H1b: Coaches’ democratic leadership style has an impact on suppression strategy.

H1c: The explanatory and rewarding leadership style of the coaches has an effect on the suppression strategy.

H1d: Coaches’ autocratic leadership style has an impact on suppression strategy.

H2a: Coaches’ educative and supportive leadership style has an effect on cognitive reappraisal strategy.

H2b: Coaches’ democratic leadership style has an effect on cognitive reappraisal strategy.

H2c: The explanatory and rewarding leadership style of the coaches has an effect on the cognitive reappraisal strategy.

H2d: Coaches’ autocratic leadership style has an impact on the cognitive reappraisal strategy.

Methods

Participants

The research was carried out in the provinces of Sakarya, Bolu and in the western black sea region of Turkey. Adequate sample selection from the universe was determined as ten participants per item were included to the study. The data were obtained by convenience sampling technique. 185 individual and 193 team athletes participated in the research. A total of 378 athletes, 168 women and 210 men, over the age of 15, who trained with coaches for at least one season as licensed, participated in the research.

Ethical Approval

Written approval (Ref No: 12.08.2022-83231/176-09) was obtained from Bayburt University Ethics Committee for this study.

Procedures

The “Leadership for Sports Scale” developed by 1980 Chelladurai and Saleh (9) and adapted into Turkish by 2008 Güngörmüş et al., (26) was used to measure the athlete’s perceptions of coaches’ leadership behaviors. The scale, which explains 38% of the total variance, consists of 34 items and 4 dimensions (12 items for educational and supportive behavior, 10 items for democratic behavior, 7 items for explanatory and rewarding behavior, and 5 items for autocratic behavior).

The Cronbach Alpha reliability value of the scale used in this study; The educational and supportive behavior was determined as “0.93”, the democratic behavior as “0.92”, the explanatory and rewarding behavior as “0.87”, the autocratic behavior as “0.85” and the total scale was determined as “0.94”.

In addition, the “Emotion Regulation Scale” developed by 2003 Gross and John (24) to determine the emotion regulation strategies of athletes and whose psychometric properties were examined in Turkish by 2021 Tingaz et al., (54), was used. The scale, which explains 53.66% of the total variance, consists of 8 items and two dimensions (Cognitive rearrangement, Suppression).The Cronbach’s Alpha reliability values of the scale used in study were determined as “0.67” for the “Cognitive Reappraisal” sub-dimension and “0.72” for the “Suppress

ion sub-dimension”.

Data Collection and Data Analysis

Some of the data were obtained through Google form and some were obtained through face-to-face survey applications. Among the data obtained from 390 athletes, the data of 12 athletes were decided to be excluded as they did not meet sampling suitability criteria, contained incomplete information, created extreme value, and did not meet Mahalanobis multiple normality criteria. The data of the remaining 378 participants were analyzed using the SPSS 24 statistical program.

In the study, the distribution of the data on the demographic characteristics of the athletes is shown with frequency and percentage. Interaction situations between dependent and independent variables were tested with multiple regression analysis. The linear relationship between the dependent and ındependent variables was tested with the correlation test. Statistical significance value (p<0.05) was interpreted based on the criterion (see Table 1 and 2).

Table 1. “CLB” and “AERS” Skewness and Kurtosis Values

| Leadership scale sub-dimensions | Number of Items | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| Educational and supportive | 12 | 378 | 2.50 | 5.00 | 4.47 | -1.060 | 0.497 |

| Democratic behavior | 10 | 378 | 1.30 | 5.00 | 4.03 | -0.804 | 0.142 |

| Descriptive and rewarding 7 | 7 | 378 | 2.29 | 5.00 | 4.48 | -1.207 | 1.362 |

| Autocratic behavior | 5 | 378 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.56 | 0.536 | -0.612 |

| Emotion regulation Scale sub-dimensions | Number of Items | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| Cognitive reappraisal | 4 | 378 | 2.00 | 7.00 | 5.35 | -0.694 | 0.669 |

| Repression | 4 | 378 | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.21 | -0.152 | -0.720 |

According to Table 1, the skewness and kurtosis values of the sub-dimensions are between (+1.5 and -1.5). It can be said that the data provides the normality distribution (51).

Table 2. Correlation Test Results Between Variables

| Repression | Cognitive Reappraisal | Supportive | Democratic | Explanatory | Autocratic | ||

| Pearson Correlation | Repression | 1.000 | ,232*** | -,146 | -,057 | -,099 | ,417 |

| Cognitive Reappraisal | ,232** | 1,000 | ,131 | ,157 | ,205 | ,110 | |

| P | Repression | . | ,000 | ,002 | ,133 | ,027 | ,000 |

| Cognitive Reappraisal | ,000 | . | ,005 | ,001 | ,000 | ,017 |

In Table 2, “democratic leadership” was excluded from the model since there was no statistically significant relationship between democratic leadership and suppression strategy (11). Since the correlation coefficients of the independent variables are below 0.9, it can be said that there is no multicollinearity between the independent variables. It has been determined that the VIF (between 1.035 and 3.114) and Tolerance (between .321 and .966) values are in the appropriate range, that is, they do not show multiple co-linearity problems. Also, Normality of differences/residues; The histogram distribution was evaluated according to the Normal P-P Chart and the scatter plot, and it was found that it showed a distribution close to the normal distribution.

Findings

Findings regarding the descriptive statistics of the data obtained in this part of the study are presented with tables (see Table 3 and 4).

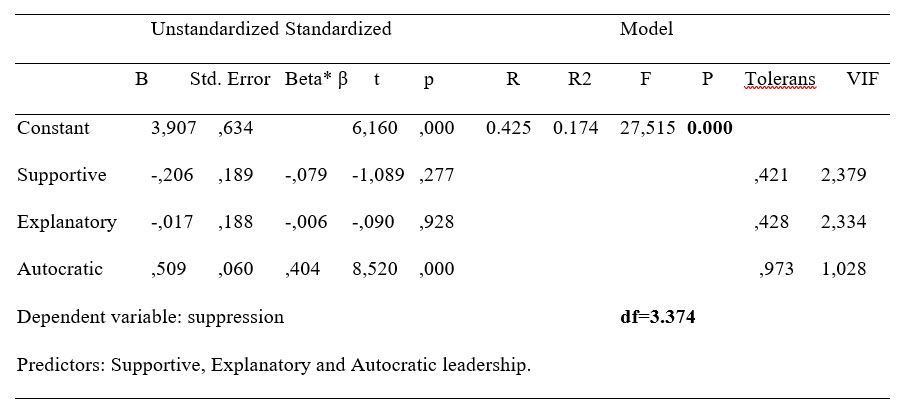

Table 3. The Effects of Leadership Behavior Dimensions on Athletes’ Suppression Strategy – Multiple Regression Analysis

According to Table 3, the relationship model between the leadership behaviors of the coaches and the suppression level of the emotion regulation dimensions of the athletes is statistically significant (F (3,374) = 27,515 p<0.00). Leadership behaviors of their coaches is explaining the suppression strategy by 17% (R= .425; R2=0.174). When the table is examined, it is seen that only the effect of autocratic leadership behavior on the suppression strategy is positive and statistically significant (β = .404; p<0.000), while the effect of other dimensions is meaningless (β = -.079; -.006 p>0.000). Therefore, the H1d hypothesis was accepted.

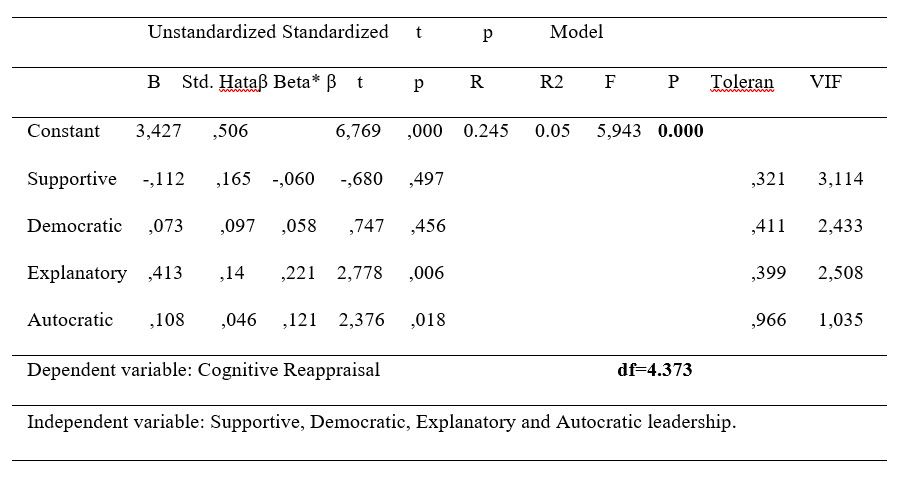

Table 4. The Effect of Coaches’ Leadership Behaviors on Athletes’ Cognitive Reappraisal Strategy – Multiple Regression Analysis

In Table 4, it is seen that the relationship model between the dimensions of the leadership behaviors of the coaches and the cognitive reevaluation level of the athletes, which is one of the emotional regulation dimensions, is statistically significant (F (4,373) = 5,943 p<0.00). The findings show that the descriptive and autocratic leadership behavior, which is one of the dimensions that make up the leadership behaviors of coaches, has a positive and statistically significant effect on the “Cognitive Reappraisal” strategy (β = ,221; β = ,121; p<0,000). Accordingly, the independent variable leadership sub-dimensions explain the cognitive reappraisal strategy of the athletes at a rate of 5% (R=.245, R2=.05). Therefore, H2c and H2d hypothesis was accepted.

Discussion

In the research, the autocratic leadership behavior was exhibited by the coaches while the “suppression” and “cognitive re-evaluation” emotion regulation strategy was apparent among athletes. It was also found that the explanatory/rewarding leadership behavior of the coaches had a positive and significant effect on the “cognitive re-evaluation” strategy of the athletes.

According to these results, the coach’s tendency towards “autocratic” and “explanatory/rewarding” leadership behavior increases the sense of suppression of the athletes. In addition, the coach’s orientation towards “explanatory/rewarding” leadership behavior also increases the cognitive reappraisal of the athletes.

When the reasons for the result related to the first hypothesis of the research are investigated, the behaviors of the coaches and the reactions of the athletes to these behaviors are apparent. Results indicate that athletes may have negative feelings towards the coaches who are in the leading position (25) which leads the athletes to demonstrate suppression behavior due to several reasons. First, coaches use punishment and reward power in accordance with the autocratic leadership behaviors in the sportive process (25). Second, athletes do not have a say in the decision-making process and that they expect unconditional obedience (48). Finally, athletes only have to fulfill the instructions they receive from their trainers (17). The combination of these conditions support the suppressive behavior of athletes and potentially negative feelings towards coaches the (25).

The trainer’s tendency to facilitate negative emotional experiences through autocratic leadership behavior leads athletes to the use of the emotion of suppression as a regulation strategy (35). Younger individuals, especially, are not typically ready to use certain emotion regulation strategies in the early period of athletics due to the intensity of their emotions. For this reason, young people use the suppression strategy until they are ready to use more efficient strategies such as rearrangement or distraction (32). On the other hand, young individuals may suppress their emotions due to the fact that he or she may not ready to express their emotions and do not know how to ask for help from a coach in emotional issues (3).

The “suppression” strategy, which is one of the strategies that athletes use consciously or unconsciously to reduce their emotional intensity, is a kind of reaction regulation behavior (23). Trainers should be aware of emotion regulation strategies in this process and should also support the emotion regulation activities of the athletes. When coaches cope with the factors that cause athletes to suppress their emotions, a coach-athlete relationship of trust, communication and support is facilitated. The quality of this relationship positively supports the psychological and physical well-being, performance and motivation of the athlete (30, 50).

The fact that the coaches offer reasons and options to their athletes before and during competition or training, and the acceptance of the emotions of the athletes allows the coaches to avoid a rigid understanding of control. In addition, supporting their own autonomous behaviors and evaluating the performance of athletes without comparing them with other athletes (41, 46) may prove to be more successful in contributing to the emotion regulation of athletes who are using suppression.

According to the second hypothesis of the research, coaches’ autocratic and explanatory/rewarding leadership style positively affects the cognitive reappraisal strategy of athletes.

Explanatory and rewarding leadership is a leadership style in which the coach gives confidence to his athletes, clearly expresses his expectations from the athletes, explains to the athlete what his strengths and weaknesses are, and appreciates the athlete when he performs a good job (26).

The explanatory and rewarding leader exhibit a more motivational, rational leadership behavior that gives insight to the athlete and appeals to his/her feelings. Coaches who adopt autocratic leadership behavior exhibit behaviors that are more task-oriented, ensure the fulfillment of tasks, and give more importance to the result. In autocratic leadership, coaches display a more control-oriented behavior that does not allow athletes to be involved in any decision-making process (5).

Although the explanatory and autocratic leader behaviors mentioned above are two contrasting leadership styles, it is seen that both styles have a positive effect on cognitive reappraisal, which is the emotion regulation sub-dimension. Cognitive reevaluation is the restructuring of a positive or negative event in a way that changes the effect of the emotions aroused in the individual (athlete) (23). In this context, it is understandable that athletes turn to cognitive reappraisal strategy in the face of positive/negative situations (explanatory/autocratic leadership behavior) encountered in the sportive process. In other words, it is expected that athletes tend to direct their emotions and restructure them when they feel extremely happy or frustrated during the sporting process (49).

Conclusions

In this study, it was revealed that explanatory and rewarding leadership and autocratic leadership, which are among the leadership behaviors of the coach, affect the emotion regulation process of the athletes. As a result, as the leadership behaviors of the coaches develop in a positive way, the emotion regulation status of the athletes will be positively affected as well. Results indicate that as the attitudes of the coaches negatively increase, the emotional states of the athletes will also be negatively affected.

Applications in Sport

Since leadership and emotion regulation strategies may have different effects in different genders, conducting studies examining the emotion regulation dynamics between male coaches and male athletes, female coaches and female athletes, and female coaches and male athletes can fill another important gap. In addition, coaches should direct their leadership behaviors in a way that will arouse positive emotions in the athlete and support the well-being of the athlete.

THANKS

Contribution Rate Statement Summary of Researchers

The authors declare that they have contributed equally to the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of the article declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

1. Aldao, A., Hoaksema, S. N. & Scweizer, S. (2010), Emotion-Regulation Strategies Across Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review, Clinical Psychology Review, 30 (2), 217-237.

2. Allan, V. & Cote, J. (2016). A cross-sectional analysis of coaches’ observed emotion-behavior profiles and adolescent athletes’ self-reported developmental outcomes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28, 321-337.

3. Arnold, K. A., Connelly, C. E., Walsh, M. M., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2015). Leadership styles, emotion regulation, and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 481–490.

4. Bandura, C. T., Kavussanu, M., & Ong, C. W. (2019). Authentic leadership and task cohesion: The mediating role of trust and team sacrifice. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 23(3-4), 185–194.

5. Baric R., & Bucik, V. (2009). Motivational differences in athletes trained by different motivational and leadership profiles. Kinesiology, 4(2), 181-194.

6. Boardley, I. D., Jackson, B., & Simmons, A. (2015). Changes in task self-efficacy and emotion across competitive performances in golf. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 37, 393-409.

7. Boss, A. D., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (2008). Everyone fails! Using emotion regulation and self-leadership for recovery. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23, 135-150.

8. Brundin, E., Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2008). Managers’ emotional displays and employees’ willingness to act entrepreneurially. Journal of Business Venturing, 23, 221-243.

9. Chelladurai, P., Saleh, S.D. (1980). Dimensions of Leader Behavior in Sports: Development aLeadership Scale, Journal of Sport Psychology, 2, 34-45.

10. Chelladurai, P., Imamura, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Oinuma, Y., et al. (1988). Sport leadership in a cross-national setting: The case of Japanese and Canadian university athletes. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 10(4), 374–389.

11. Cevahir, E. (2020). SPSS ile nicel veri analizi rehberi. İstanbul Kibele Yayınları.

12. Chelladurai, P. (1990) Leadership in sports: a review. Int J Sport Psychol, 21, 328–354.

13. Cote, S. (2005). A social interaction model of the effects of emotion regulation on work strain. Academy of Management Review, 30, 509-530.

14. Dasborough, M. T., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2002). Emotion and attribution of intentionality in leader – member relationships. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 615 – 634.

15. Dirks, K. T. (2000). Trust in leadership and team performance: Evidence from NCAA basketball. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(6), 1004–1012.

16. Eldeleklioğlu, J. & Eroğlu, Y. (2015). Turkish version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Journal of Human Sciences, 12 (1), 1157–1168.

17. Eren, E. (2001). Management and organization. Istanbul: Beta Publications.

18. Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V. & Spinhoven, P. (2001), Negative Life Events, Cognitive Emotion Regulation and Emotional Problems. Personality and Invdividual Differences, 30 (8), 1311-1327.

19. Gillet, N., Vallerand, R. J., Amoura, S., & Baldes, B. (2010). Influence of coaches’ autonomy support on athletes’ motivation and sport performance: A test of the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(2), 155–161.

20. Gokce, G. (2013). Parent’s Emotional Availability and General Psychological Health: The Role of Emotion Regulation, Interpersonal Relationship Style and Social Support (Unpublished Master’s Thesis). Ankara University, Ankara.

21. Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader – member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multilevel multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6 (2), 219 – 247.

22. Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2, 271- 299.

23. Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281-291.

24. Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348.

25. Guner, S. (2002). Evaluation of Transformational Leadership in Terms of Power Resources and Suitability of the Armed Forces Organization for Transformational Leadership. (Master’s Thesis). Süleyman Demirel University Institute of Social Sciences, Isparta, Turkey.

26. Güngörmüş, H. A., Gürbüz, B. & Yenel, F. (2008). Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the version of the Sports Leadership Scale for the perception of the behavior of the coach by the athletes, Atatürk University Journal of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, 10 (2), 16-22.

27. Hanin, Y. L. (2000). Individual zones of optimal functioning (IZOF) model. In Y. L. Hanin (Ed.), Emotions in sport (pp. 65-89). Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics.

28. Humphrey, H. R. (2002). The many faces of emotional leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 493-504.

29. Humphrey, R. H., Pollack, J. M., & Hawver, T. (2008). Leading with emotional labor. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23, 151–168.

30.Isoard-Gautheur, S., Trouilloud, D., Gustafsson, H., & Guillet-DESCAS, E. (2013). Associations between the perceived quality of the coac- heathlete relationship and athlete burnout: An examination of the mediating role of achievement goals. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 22, 210-217.

31. Işık, A. & Turan, F. (2015). Emotion Regulation in Children with Normal Development and Autism Spectrum Disorder . Hacettepe University Faculty of Health Sciences Journal, 3rd National Congress of Child Development and Education (International Participations) (Congress Book) /7893/103935.

32. John, P. O., & Gross, J. J. (2004). Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. Journal of Personality, 72, 1301- 1333.

33. Jones, M.V. (2003). Controlling emotions in sport. The sport Psychologist. 17,471-486.

34. Jones, M. & Uphill, M. (2012). Emotion in sport: Antecedents and performance consequences. In Thatcher, J., Jones, M., & Lavallee, D. (Eds.), Coping and emotion in sport (pp. 33- 61). New York: Routledge.

35.Kalokerinos, E. K., Résibois, M., Verduyn, P., & Kuppens, P. (2016). The temporal deployment of emotion regulation strategies during negative emotional episodes. Emotion. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/emo0000248

36. Kim, H.-D., & Cruz, A. B. (2016). The influence of coaches’ leadership styles on athletes’ satisfaction and team cohesion: A meta-analytic approach. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 11(6), 900–909.

37. Kocabıyık, O., Çelik, O. & Dündar, H. (2017). Investigation of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Styles of Young Adults in Terms of Relational Dependent Self-Construction and Gender, Marmara University Atatürk Faculty of Education Journal of Educational Sciences, 45, 79-92.

38. Konar-Goldband, E., Rice, R. W., & Monkarsh, W. (1979). Time-phased interrelationships of group atmosphere, group performance, and leader style. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(4), 401–409.

39. Lazarus, R. S. (2000). Cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. In Y. L. Hanin (Ed). Emotions in sport (pp. 32-63). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

40. Lemelin, E., Verner-Filion, J., Carpentier, J., Carbonneau, N., & Mageau, G. A. (2022). Autonomy support in sport contexts: The role of parents and coaches in the promotion of athlete well-being and performance. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(3), 305–319.

41. Mageau, G. A., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). The coach–athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(11), 883-904.

42. Malloy, E., Kavussanu, M., & Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M. A. (2022). Changes in authentic leadership over a sport season predict changes in athlete outcomes. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 11(3), 275–289.

43. Matosic, D., Cox, A. E., & Amorose, A. J. (2014). Scholarship status, controlling coaching behavior, and intrinsic motivation in collegiate swimmers: A test of cognitive evaluation theory. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 3(1), 1–12.

44. McColl-Kennedy, J. R., & Andersen, R. D. (2002). Impact of leadership style and emotions on subordinate performance. Leadership Quarterly, 13, 545 – 559.

45. Northouse, P. C. (2004). Leadership: Theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

46. Pope, J. P., & Wilson, P. M. (2015). Testing a sequence of relationships from interpersonal coaching styles to rugby performance, guided by the coach–athlete motivation model. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(3), 258-272.

47. Rocchi, M. A., Guertin, C., Pelletier, L. G., & Sweet, S. N. (2020). Performance trajectories for competitive swimmers: The role of coach interpersonal behaviors and athlete motivation. Motivation Science, 6(3), 285–296.

48. Sarı, I. (2007). Transformational Leadership. (PhD Thesis). Kahramanmaras Sutcu Imam University, Kahramanmaras, Turkey.

49. Schall, M., Martiny, S. E., Goetz, T., & Hall, N. C. (2016). Smiling on the inside: The social benefits of suppressing positive emotions in outperformance situations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(5), 559-571.

50. Staff, H. R., Didymus, F. F., & Backhouse, S. H. (2017). Coping rarely takes place in a social vacuum: Exploring antecedents and outcomes of dyadic coping in coach-athlete relationships. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 30, 91-100.

51. Tabachnick, B. G. And Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics. Boston, Pearson.

52. Tamminen, K. A., & Holt, N. L. (2012). Adolescent athletes’ learning about coping and the roles of parents and coaches. Psychology of sport and exercise, 13(1), 69-79.

53. Thelwell, R. C., Lane, A. M., Weston, N. J., & Greenlees, I. A. (2008). Examining relationships between emotional intelligence and coaching efficacy. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6, 224-235.

54. Tingaz, E, O., & Altun-Ekiz, M. (2021). Adaptation of the emotion regulation scale for athletes and examination of its psychometric properties. Gazi Journal of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, 26(2), 301-313.

55. Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, L. B. (2007). Regulation of positive emotions: Emotion regulation strategies that promote resilience. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 311-333.

56. Vallerand, R. J. ve Blanchard, C. M. (2000). The study of emotion in sport and exercise: Historical, definitional, and conceptual perspectives. In Y. L. Hanin (Ed.), Emotions in sport, Human Kinetics. (s. 3–37).

57. Vargas-Tonsing, T. M. (2009). An exploratory examination of the effects of coaches’ pre-game speeches on athletes’ perceptions of self-efficacy and emotion. Journal of Sport Behavior, 32, 92-111.

58. Weinberg, R, Gould, D. (2015) Foundations of sport and exercise psychology, 6th ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics,

59. Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.