The Impact of Hip Rotator Strength Training on Agility in Male High School Soccer Players

Submitted by Jesse Obed Nelson and Mark DeBeliso

ABSTRACT

The strength of the muscles surrounding a joint contributes to the stability of the joint. The stability of a joint provides the foundation for large muscle groups to perform high speed forceful actions. The purpose of this study was to examine if strengthening of the hip rotator muscles could improve measures of agility. Twenty-nine male high school soccer players were recruited to participate in a 9-week matched pair study. The control and the experimental group participated in regular weight training and soccer practice. Additionally, the experimental group performed three sets of the hip rotator exercises using latex chords (medial and lateral rotation) twice per week with both legs. The dependent variables were the T-Test, the Hexagon Test, and the 20-Yard Shuttle Run. All athletes were pre- and post-tested on each of the agility drills. A gain score was then calculated as the difference between pre- and post-test agility scores. An independent t-test was used to determine if there were any differences (p < 0.05) between the experimental and control groups. Statistical analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups for T-test (p=0.12), Hexagon test (p=0.35), and 20-yard shuttle run (p=0.18). The research hypothesis, which stated that adding hip strengthening exercises for the experimental group would produce faster times on the agility tests, was rejected. Possibly the volume of training, which often included three hours of exercise and practice per day, rendered the additional hip strengthening exercises insignificant. Repeating the experiment in the off-season with lower training volume might produce different results.

INTRODUCTION

In sport and physical therapy there is not much time spent in training the medial and lateral rotators of the hip, while medial and lateral rotators of the arm (rotator cuff) are regularly exercised (15, 17). The deep inner muscles of the hip are often neglected and overlooked in the development of training programs for all types of sport.

Field sports which might benefit from strengthening of the hip rotators are those which require movements of agility (e.g. soccer, football, lacrosse, rugby, and basketball). Agility requires rapid change of direction. This is where stronger hip rotator muscles may help athletes. An increase in performance might be experienced as a result of stronger hip rotator muscles.

Injury rate reduction might also be a benefit of improving the strength of the hip rotator muscles. Sports that include running, dancing, and hockey are at increased risk of hip injuries (2, 7). Recent investigations suggest that 23% of athletes (e.g. divers, weightlifters, wrestlers, orienteers and ice-hockey players) have experienced a hip injury in the previous year (12). Muscle weakness is an intrinsic risk factor to joint injuries in sport (18). Strengthening of the hip rotator muscles is prehabilitative in nature, much the same as training the internal and external rotator cuff muscles (17). Prehabilitation is a concept where muscle groups are exposed to various exercise protocols with the hope of reducing the occurrence and severity of sport injuries (16, 17). A prehabilitative program for Rugby Union players identified the lower body including the hip as a specific target, however, isolated training of the hip rotator muscles was not included (16).

Internal and external hip rotator muscles include the adductor longus, adductor magnus, biceps femoris, gemellus inferior, gemellus superior, gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, gracillis, illiacus, obturator externus, obturator internus, piriformus, psoas, quadratus femoris, sartorius, semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and tensor fascia latae (11). There is a paucity of research examining the role of the hip rotator muscles in sport and prehabilitation. As such, this research effort focused on the impact of incorporating exercises that target the hip rotator muscles on sport-specific agility tests.

The research hypothesis is that, after training, the experimental group will show significant improvements versus the control group on the T-test, Hexagon test, and the 20-yd shuttle run. These tests are indicators of speed and agility (23), and are considered sport performance characteristics of the “best soccer” players (23). Hence, the purpose of adding the hip rotation exercises was to determine if there would be a positive influence on speed and agility. Conversely, the null hypothesis was that the addition of hip rotation exercises to the training program for the experimental group would not yield better performance on the agility drills than the control group.

If the research hypothesis is supported, coaches and athletes might incorporate hip rotator exercises to strength and conditioning regimens leading to improved agility. This research could also provide the foundation for future experiments regarding medial and lateral hip rotator muscles and the relation to sport performance.

METHODS

A convenience sample of male high school soccer players (n=29) was recruited to participate in a 9-week matched pair study. The participants were experienced in weight training, and trained and experienced at the competitive level in the sport of soccer. As such, participant fitness levels were likely above average for those of the same age and gender.

Age, weight, and height were recorded at the pretest. For the experimental group, the average age was 16.3±0.9 years with a range of 15-18 years. The average body mass was 68.1±9.9 kg, with a range of 57-89 kg. The average height was 173.3±8.9 cm, with a range of 165-193 cm. For the control group the average age was 16.6±0.7 years, with a range of 16-18 years. The average body mass was 66.3±8.7 kg, with a range of 54-86 kg. The average height was 173.0±7.7 cm, with a range of 163-188 cm.

Previous exercise history included calisthenics, stretching, running sprints, and weight training (all performed under the supervision of the strength and conditioning coach). The players also played a friendly game (against each other) two times per week before school. The participants were all varsity and junior varsity players, and most had played soccer since elementary school. No players were classified at the beginner level. All had been active and in good physical condition for years before the beginning of the experiment.

Human Subjects Approval was required and obtained. Informed Consent and Parental Consent was also required and obtained before subjects were allowed to participate in the study. Participants were allowed to withdraw at any time. The Informed Consent Document was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

In order to conduct this study an experimental and control group were formed using a matched pair design (5). All of the participants performed the agility T-test, and then ranked from fastest to slowest. The first two highest scoring participants were matched and randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. This process was repeated until the experimental (n=14) and control (n=15) groups were completed. This matched pair design assured that the two groups were essentially equal based on initial T-test scores.

Equipment for the strength and conditioning program was that traditionally found in many high school weight rooms. Iron plates were loaded onto weight bars for the squat, the deadlift, and other exercises. All of the athletes in both the experimental and control groups performed the same weight training exercises with the strength and conditioning coach. The training volume was the same for the experimental and control groups with the exception of the additional volume incurred by the experimental group as a result of performing the supplemental internal and external hip rotation exercises.

Weekly workouts during the intervention included 2-3 strength and conditioning sessions per week. The school had a rotating block class schedule, alternating successive weeks with two and three strength and conditioning classes respectively. The soccer team had practice for 1.5 hours every weekday after school unless there was a “friendly game” in the morning. All team members focused on stretching and recovery, but the experimental group still performed the hip rotator exercises.

Strength and conditioning sessions began in the wrestling room with calisthenics including bear crawls, planks, sit-ups, wall sits, push-ups, and some simple jumping drills. The team would then stretch with a focus on the legs. After stretching, half of the team would work with the track coach in the hall, while the other half would work with the strength and conditioning coach to the weight room. The group in the hall performed dynamic stretching and simple footwork drills such as butt-kicks, high knees, grapevines, 10 yard sprints, and skips. The group in the weight room did differing exercises depending on the day, mostly rotating with upper body, lower body, and total body exercises. The total body exercises included dot drills, deadlifts, hang cleans, and power cleans. The dot drills, hang cleans, and power cleans were exercises where members of both groups were encouraged to move as explosively as possible during the execution of the exercises while maintaining proper technique. Upper body exercises included the flat, incline, and decline bench press, push press, military press, dumbbell shoulder press, dumbbell row, dumbbell biceps curl, dumbbell triceps press, and pull-ups. Leg exercises started with the squat, and included leg extensions, leg curls, and calf raises. The protocol for all weight room exercises was three sets of 8-12 repetitions, and three sets of five repetitions on the total body exercises. Both groups performed the same baseline training regime with the experimental group augmenting the training with hip rotator exercises.

The experimental group completed the hip rotation exercises with the elastic chords during class time. The hip rotation exercises took 5-10 minutes to complete. The athletes began by doing three sets of 5-10 repetitions in each of the four directions (right leg internal and external rotation, left leg internal and external rotation). Each set was performed to exhaustion. The athletes gradually began to perform a greater number of repetitions per set as strength levels increased. Towards the end of the 9-week period, all of the athletes were completing three sets of 20-30 repetitions in each of the four directions.

Workout chords of latex bands were fastened to an inanimate object, such as a weight stack, or to the base of a handrail, with the opposite end looped around the ankle. The participants were seated on a chair with the hip and knee both at 90 degrees of flexion. The chairs used were high enough for the participant to find 90 degrees of flexion at the hip and at the knee. The participant then swung the foot inward or outward, depending on the position relative to the attachment site of the chord. The instruction was to hold the knee joint stationary at a 90-degree angle, and the hip joint at a 90-degree angle while swinging the foot inward. The speed of the movement was set at one second moving inward, followed by a one second return to the starting position for the internal hip rotation sets (with just the opposite for the external hip rotation sets). This was the speed of movement for both inner and outer directions. The movement speed was selected in order to strike a balance between improving the strength and stability of the joint, versus the possibility of injury to the hip rotator muscles from ballistically performing the limits of the range of motion with the hip and knee joints in fixed positions. Range of motion was considered and the players were encouraged to perform the movement “as far as possible, while avoiding any sharp pain”. The exercise movement patterns for the hip rotation exercises were consistent during the study.

Workout chords (UltrafitTM Lateral Toner -Heavy) were acquired through Gopher Sports, Owatonna, MN. The product is a 23 cm long latex chord attached to a 36 cm Velcro ankle wrap (17 kg elastic tension force rating). Similar resistance chords (elastic tubing) have been demonstrated to elicit similar EMG and indicators of muscle damage as that experienced with isotonic training equipment (1, 10). The chords allowed for near ideal positioning of the hip and knee angles in order to isolate the hip rotator muscles for medial and lateral rotation.

For the pre- and post-tests the “stopwatch” application was used on the iPhone (Apple, Inc.) to time the T-test, Hexagon test, and the 20-yard (65.6 m) shuttle run (also known as the pro-agility test). Handheld timing devices are considered acceptable for tests of speed and agility (23). The “notes” iPhone application was used to record the names, height, weight, and scores for each of the participants. Three scorers were used, one for each of the tests, each scorer having an iPhone. When the testing was completed, the scorers emailed the information directly to the researcher using the iPhone. This procedure protected the data against any type of hand transfer error, by keeping the scoring and transfer of data completely electronic. After the data was collected and emailed to the researcher, the other two scorers deleted all information. The same three scorers were used for both the pre-test and post-test, to ensure reliability (23). A meeting was held before each test battery (pre and post-tests). The researcher instructed the scorers how to correctly administer the tests. The researcher and the three scorers practiced setting up the tests and conducted trial runs with each other as a rehearsal.

Three scorers (including the researcher) set up the three agility drills. The reliability of the T-test (r=0.98) (19), the Hexagon test (“excellent reliability”) (6) and the 20-Yard Shuttle Run (r=.96) (21) have been previously reported. Exact procedures for these drills were obtained at http://www.topendsports.com. Participants were allowed one practice trial for each test. Following the practice trials, each test was repeated twice. All data was collected by the scorers and emailed directly to the researcher. The pre- and post-tests took place in the high school hallway. The post-tests took place the Monday following the last training session (72-96 hours).

The entire 9-week study was conducted during the soccer pre-season. Adherence to the program was monitored by the coach and the researcher by taking attendance. Absences were noted by the coach. Absences were rare, and there were no adherence problems.

After the 9 weeks were completed, the post-tests were administered in the same manner as the pre-tests. Scores were recorded in the same manner, using the same recorders. The data was then compared and analyzed, using Microsoft Excel ™. A gain score was calculated for each dependent variable that was equal to the difference between the post and pretest score. The gain score for each dependent variable was then compared between groups via an independent t-test with the significance level at < 0.05..

RESULTS

Two scores were collected at the pre-test and at the post-test for each dependent variable (T-Test, Hexagon Test, and 20-yard Shuttle Run). The “better” of the two scores was considered indicative of the maximum effort performance, and hence were used for analysis. Each dependent variable was measured in seconds.

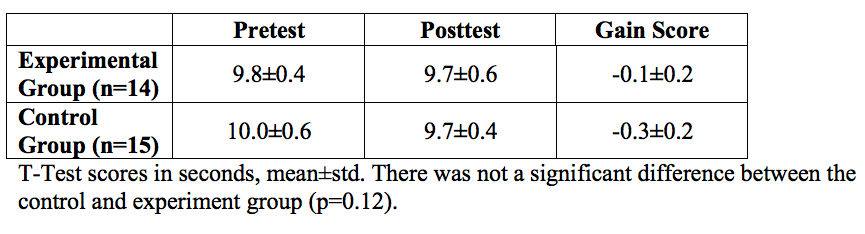

T-Test

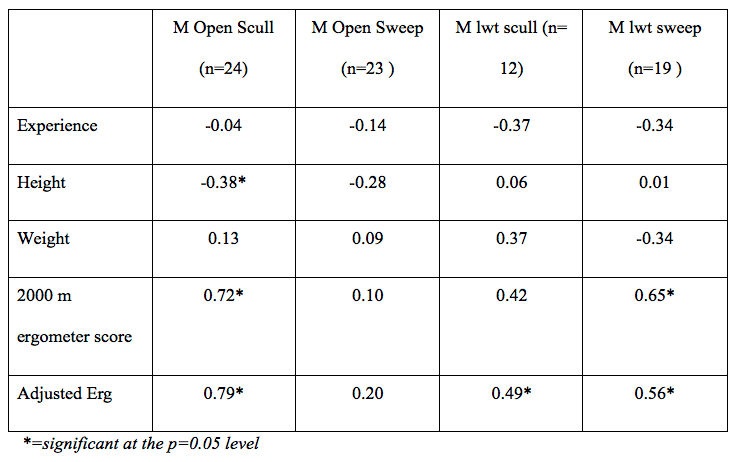

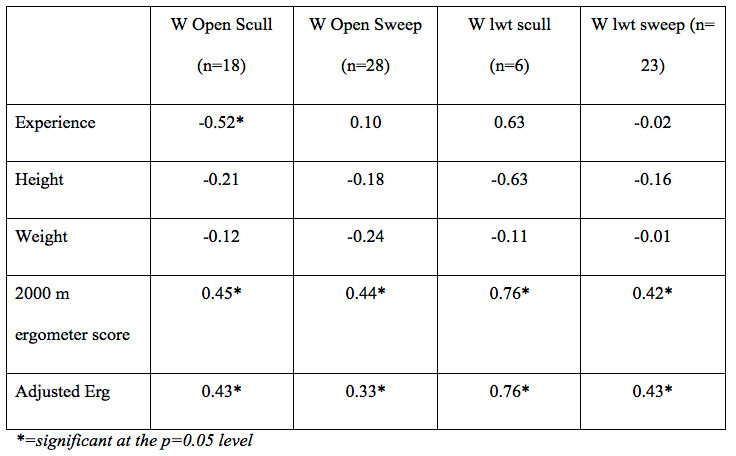

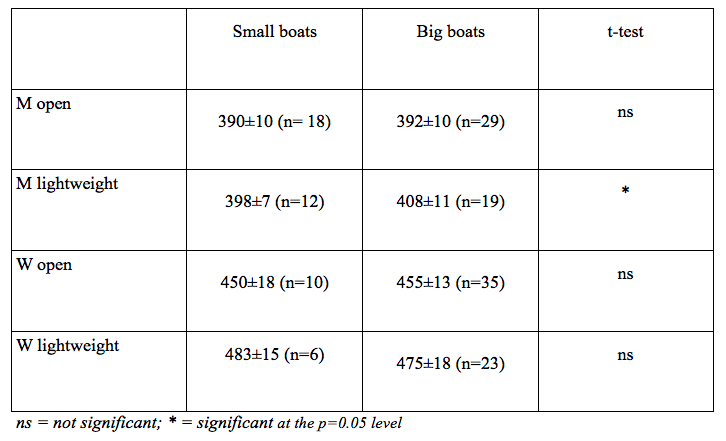

The experimental group scores were (mean±sd) pre=9.8±0.4, post=9.7±0.6, gain=-0.1±0.2. The control group scores were pre=10.0±0.6, post=9.7±0.4, gain=-0.3±0.2. The range of pre to post scores for both the experimental and control group compare favorably with and slightly faster than previously published T-Test scores for Elite U-16 soccer players (23). There was not a significant difference in gain scores between groups (p=0.12). Table 1 provides the details of the pre and posttest measures of the T-Test.

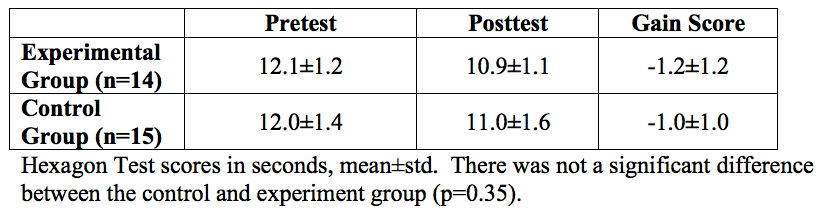

Hexagon Test

The experimental group scores were (mean±sd) pre=12.1±1.2, post=10.9±1.1, gain=-1.2±1.2. The control group scores were pre=12.0±1.4, post=11.0±1.6, gain=-1.0±1.0. The range of pre to post scores for both the experimental and control group compare favorably with and slightly faster than previously published Hexagon test scores for male recreational college athletes (4). There was not a significant difference in gain scores between groups (p=0.35). Table 2 provides the details of the pre and post measures of the Hexagon Test.

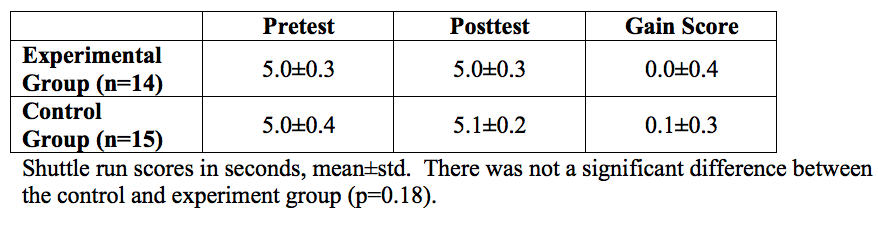

20 Yard Shuttle Run

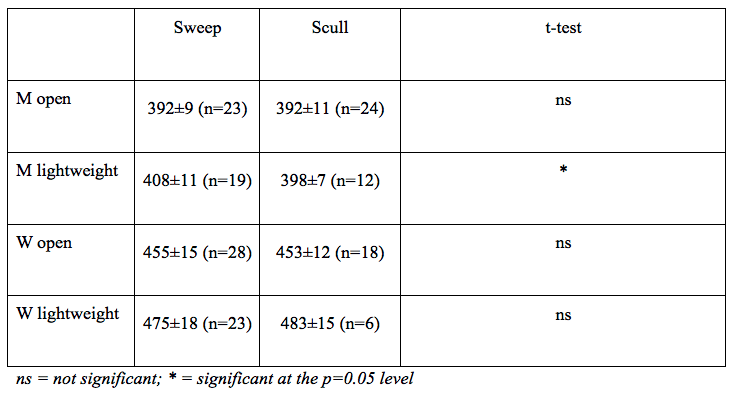

The experimental group scores were (mean±sd) pre=5.0±0.3, post=5.0±0.3, gain=0.0±0.4. The control group scores were pre=5.0±0.4, post=5.1±0.2, gain=0.1±0.3. The range of pre to post scores for both the experimental and control group compare favorably with and slightly slower than previously published 20 yard Shuttle Run Test scores for male NCAA Division III soccer athletes (23). There was not a significant difference in gain scores between groups (p=0.18). Table 3 provides the details of the pre and post measures of the 20-yard shuttle run.

Table 3. 20-Yard Shuttle Run Results

The results from all three tests indicated that there was not a significant difference at the 0.05 level in performance between the experimental and the control group. The researchers failed to reject the null hypothesis. The addition of hip rotation exercises to the training program for the experimental group did not improve performance on the agility drills versus control.

DISCUSSION

Previous research exploring means to improve agility in soccer players has focused on strength training, plyometrics, plyometrics combined with strength training, stretching modalities, and acute exercise protocols (3, 8, 9, 13, 14, 20, 22). Plyometrics, strength training, and plyometrics combined with strength training have been demonstrated to improve performance on agility tests in soccer players (9, 14, 20, 22). However, studies regarding stretching modalities (PNF, static, dynamic) and acute exercise protocols are inconclusive with respect to improving performance on agility tests (3, 8, 13). There are no other published studies investigating training of the hip rotator muscles. This study was a pioneering research experiment to determine if strengthening hip rotator muscles using latex bands could lead to improved athletic performance on agility tests. The importance of this concept brings training of hip rotator muscles into sport performance. These hip rotational exercises could be readily added to a regular strength and conditioning program.

This study introduces the concept of training hip rotator muscles into practice. By using latex chords, soccer players were able to train hip rotator musculature. In retrospect some of the players expressed feeling a difference while doing these exercises over the weeks of time. After the posttests were completed, the elastic chords were given to the Coach. The general sense from the participants was that training the hip rotator muscles was beneficial and could make a positive difference. Hence, the team continued training the hip rotator muscles with the elastic chords following the conclusion of the study. One possible reason that improvements in agility were not observed with augmented training of the hip rotator muscles was due to the large overall volume of training for both groups. The experiment was performed during the preseason transition into the regular season where training volume is high.

The researchers were unable to establish a measurable benefit from the intervention. Possibly, relative effort was related to degree of gain. Those exhibiting the greatest effort during training (from either group) experienced the greatest improvements. Some subjects may have been more motivated to work hard and win a championship, particularly the older players. Possibly, some may have trained or performed harder when influenced by a friend. The level of motivation and social acceptance may relate to work ethic. Although the research hypothesis had to be rejected, hip rotation exercises may have value in strength training programs. There may be other training programs with hip rotation exercises in favor of the research hypothesis.

The preseason workload was formidable. The beneficial expression of hip rotator supplemental exercises was possibly limited due to the large volume of other weekly exercises. If the experiment is to be repeated, one might consider the off-season when many of the variables (including total workload) can be better controlled. For example, the team could weight-train for an hour, three times per week, without the limitations of a class period (summer break). Additionally, a specific time for the experimental group to do the hip rotation exercises could be scheduled after both groups have completed the common portions of the strength training protocols together. For example, half of the players could stay after the hour-long training session for an additional 5 to 10 minutes to perform the hip rotation exercises.

A criticism of this study might focus on the repetitions and intensity in the study protocol for the hip rotator exercises. Strength protocols require higher intensity resistance with fewer repetitions whereas endurance prescribes higher repetitions with lower resistance. Arguably, the wording of the title of the study could be changed to “endurance” or “prehabilitation”. There is a relationship between muscular strength and endurance, and the small rotator muscles of the hip were isolated and exposed to focused resistance training. Nerves command muscles to pull on bones to stabilize and generate movement about joints. In theory, the nerves and motor units commanding these actions should have become stronger in response to the resistance-training stimulus. Considering the lengths, origins, and insertions, these small muscles do not create enormous amounts of torque, however, these muscles do stabilize the joint socket. The larger muscles of the legs and core move the body. The concept is to improve the stability of the joint, in turn, allowing the larger muscles to have a more stable frame to pull on. Providing the larger muscles with a more stable frame should allow for the generation of faster, more powerful movements. Further, as with the rotator cuff muscles, resistance training with high intensity and lower repetitions could be potentially hazardous to the hip rotator muscles.

Both the experimental and control groups performed total body exercises including dot drills, hang cleans, and power cleans. The dot drills, hang cleans, and power cleans were exercises where members of both groups were encouraged to move as explosively and fast as possible during the execution of the exercises while maintaining proper technique. Conversely, the tempo of the execution of the hip rotator exercises was 1:1 (seconds), with one second moving inward, followed by a one second return to the starting position for the internal hip rotation sets (with just the opposite for the external hip rotation sets). The movement speed was selected in order to strike a balance between improving the strength and stability of the joint, versus the possibility of inducing an injury to the hip rotator muscles. Ballistic movements into the limits of the range of motion may affect short or long-term risk of injury while the hip and knee are in fixed positions.

The research hypothesis was that the speed of movement and power developed as a result of performing dot drills, hang cleans, and power cleans would be better exhibited by the experimental group due to the introduction of the hip rotator exercises. The addition of hip rotator exercises was hypothesized to develop speed and power to a greater degree while performing other exercises (dot drills, hang cleans, and power cleans). Future studies might focus on the tempo of performing the hip rotator exercises. From a specificity standpoint, hip rotator exercises may need to be performed at a faster pace in order to better transfer the speed and power developed for agility performance.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, although the research hypothesis was rejected, hip rotation exercises may still prove to be a valuable part of a strength-training program. With additional sport-related studies, the importance of hip rotation exercises augmenting a training program may prove beneficial for the enhancement of sport agility performance. These exercises may help athletes to be stronger, more agile, and less prone to injury.

APPLICATION IN SPORT

Prehabilitation is a concept where muscle groups are exposed to various exercise protocols with the hope of reducing the occurrence and severity of sport injuries (10, 11). This study could be considered prehabilitative in nature. Isolated training of the hip rotator muscles may improve the strength of the exercised muscles and enhance the long-term stability of the hip joint. Joint laxity and muscle weakness are both intrinsic risk factors for joint injury (12). A possible benefit of this study was a subsequent reduction of hip joint injuries and severity. However, the study did not include a follow up period where injury occurrences were monitored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None

REFERENCES

1. Aboodarda, S., Georg, J., Mokhtar, A., & Thompson, M. (2011). Muscle strength and damage following two modes of variable resistance training. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 10(4), 635-642.

2. Adkins, S. B., & Figler, R. A. (2000). Hip pain in athletes. American Family Physician, 61, 2109-2118.

3. Amiri-Khorasani, M., Sahebozamani, M., Tabrizi, K. G., & Yusof, A. B. (2010). Acute effect of different stretching methods on Illinois agility test in soccer players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2698-2704.

4. Baechle, T. R., & Earle, R. W. (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

5. Baumgartner, T. A, & Hensley, L. D. (2006). Conducting and reading research in health and human performance (4th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

6. Beekhuizen, K. S., Davis, M. D., Kobler, M. J., & Cheng, M. S. (2009). Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change of the hexagon agility test. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(7), 2167-2171.

7. Boyd, K. T., Peirce, N. S., & Batt, M. E. (1997). Common hip injuries in sport. Sports Medicine, 24, 273-288.

8. Bullock, W., Panchuk, D., Broatch, J., Christian, R., & Stepto, N. K. (2012). An integrative test of agility, speed and skill in soccer: Effects of exercise. Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport, 15(5), 431-436.

9. Christou, M., Smilios, I., Sotiropoulos, K., Volaklis, K., Pilianidis, T., & Tokmakidis, S. P. (2006). Effects of resistance training on the physical capacities of adolescent soccer players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 20(4), 783-791.

10. Due Jakobsen, M., Sundstrup, E., Andersen, C. H., Bandholm, T., Thorborg, K., Zebis, M. K., & Andersen, L. L. (2012). Muscle activity during knee-extension strengthening exercise performed with elastic tubing and isotonic resistance. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 7(6), 606-616.

11. Hamil, J., & Knutzen, K. M. (2009). Biomechanical basis of human movement (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

12. Jonasson, P., Halldin, K., Karlsson, J., Thoreson, O., Hvannberg, J., Swärd, L., & Baranto, A. (2011). Prevalence of joint-related pain in the extremities and spine in five groups of top athletes. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, and Arthroscopy, 19(9), 1540-1546.

13. Jordan, J., Korgaokar, A. D., Farley, R. S., & Caputo, J. L. (2012). Acute effects of static and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching on agility performance in elite youth soccer players. International Journal of Exercise Science, 5(2), 97-105.

14. Jullien, H., Bisch, C., Largouët, N., Manouvrier, C., Carling, C. J., & Amiard, V. (2008). Does a short period of lower limb strength training improve performance in field-based tests of running and agility in young professional soccer players? Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(2), 404-411.

15. Kibler, W. B. (2003). Rehabilitation of rotator cuff tendinopathy. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 22(4), 837-847.

16. Meir, R., Diesel, W., & Archer, E. (2007). Developing a prehabilitation program in a collision sport: A model developed within English premiership rugby union football. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 29(3), 50-62.

17. Mullen, G. (2010). How to prevent shoulder pain. Swimming World, 51(8), 30-31.

18. Parkkari, J. J, Kujala, U. M., & Kannus, P. P. (2001). Is it possible to prevent sports injuries? Review of controlled clinical trials and recommendations for future work. Sports Medicine, 31(14), 985-995.

19. Pauole, K. K., Madol, K. K., Garhammer, J. J., Lacourse, M. M, & Rozenek, R. (2000). Reliability and validity of the T-test as a measure of agility, leg power, and leg speed in college-aged men and women. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 14(4), 443-450.

20. Ronnestad, B. R., Kvamme, N. H., Sunde, A., & Raastad, T. (2008). Short-term effects of strength and plyometric training on sprint and jump performance in professional soccer players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(3), 773-780.

21. Thomas, C. C., Plowman, S. A., & Looney, M. A. (2002). Reliability and validity of the anaerobic speed test and the field anaerobic shuttle test for measuring anaerobic work capacity in soccer players. Measurement in Physical Education & Exercise Science, 6(3), 187-205.

22. Thomas, K., French, D., & Hayes, P. R. (2009). The effect of two plyometric training techniques on muscular power and agility in youth soccer players. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(1), 332-335.

23. Triplett, N. T. (2012). Speed and agility. In T. Miller (Eds.), NSCA’s guide to tests and assessments (1st ed., pp. 253-274). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.