Eating Disorders Among Female College Athletes

Jon Lim, Minnesota State University, United States Sports Academy Doctoral Graduate

Abstract

The study examined attitudes about eating in relation to eating disorders, among undergraduate female student-athletes and non-athletes at a mid-size Midwestern NCAA Division II university. It furthermore examined prevalence of eating disorders among female athletes in certain sports and determined relationships between eating disorders and several variables (self-esteem, body image, social pressures, body mass index) thought to contribute to eating disorders. A total of 125 students participated in the research, 60 athletes and 65 non-athletes. The athletes played softball (n = 11), soccer (n = 12), track (n = 8), cross-country (n = 5), basketball (n = 9), and volleyball (n = 15). The Eating Attitudes Test (EAT–26) was used to determine the presence of or risk of developing eating disorders. Results showed no significant difference between the athletes and non-athletes in terms of attitudes about eating as they relate to eating disorders, nor were significant sport-based differences in likelihood of eating disorders found. Additionally, no significant relationships were found between eating disorders and self-esteem, social pressures, body image, and body mass index. Findings inconsistent with earlier research may indicate that at Division II schools, athletes experience less pressure from coaches and teammates, but further research is needed in this area. Future studies should also look at the degree of impact coaches make on the development of eating disorders in athletes.

Eating Disorders Among Female College Athletes

Eating disorders (e.g., bulimia, anorexia nervosa) are a significant public health problem and increasingly common among young women in today’s westernized countries (Griffin & Berry, 2003; Levenkron, 2000; Hsu, 1990). According to the National Eating Disorder Association (2003), 5–10% of all women have some form of eating disorder. Moreover, research suggests that 19–30% of female college students could be diagnosed with an eating disorder (Fisher, Golden, Katzman, & Kreipe, 1995). A growing body of research indicates that there is a link between exposure to media images representing sociocultural ideals of attractiveness and dissatisfaction with one’s body along with eating disorders (Levine & Smolak, 1996; Striegel-Moore, Silberstein, & Rodin, 1986). The media’s portrayal of thinness as a measure of ideal female beauty promotes body dissatisfaction and thus contributes to the development of eating disorders in many women (Levine & Smolak, 1996). Cultural and societal pressure on women to be thin in order to be attractive (Worsnop, 1992; Irving, 1990) can lead to obsession with thinness, body-image distortion, and unhealthy eating behaviors.

Like other women, women athletes experience this pressure to be thin. In addition, they often experience added pressure from within their sport to attain and maintain a certain body weight or shape. Indeed, some studies have reported that the prevalence of eating disorders is much higher in female athletes than in females in general (Berry & Howe, 2000; Johnson, Powers, & Dick; 1999; McNulty, Adams, Anderson, & Affenito, 2001; Sundgot-Borgen & Torstveit, 2004; Picard, 1999). Furthermore, the prevalence of eating disorders among female athletes competing in aesthetic sports such as dance, gymnastics, cheerleading, swimming, and figure skating is significantly higher than among female athletes in non-aesthetic or non-weight-dependent sports (Berry & Howe, 2000; O’Connor & Lewis, 1997; Perriello, 2001; Sundgot-Borgen, 1994; Sundgot-Borgen & Torstveit, 2004). For instance, Sundgot-Borgen and Torstveit found that female athletes competing in aesthetic sports show higher rates of eating disorder symptoms (42%) than are observed in endurance sports (24%), technical sports (17%), or ball game sports (16%).

Female athletes and those who coach them usually think that the thinner the athletes are, the better they will perform—and the better they will look in uniform (Hawes, 1999; Thompson & Sherman, 1999). In sports in which the uniforms are relatively revealing, the human body is often highlighted. For example, track athletes usually wear a uniform consisting of form-fitting shorts and a midriff-baring tank top. Dance and gymnastics uniforms are usually a one-piece bodysuit sometimes worn with tights. Athletes who must wear the body-hugging uniforms and compete before large crowds of people are likely very self-conscious about their physiques.

However, as is the case in most areas of study, not all research agrees. Some recent studies show that athletes are no more at risk for the development of eating disorders than non-athletes (Carter, 2002; Davis & Strachen, 2001; Guthrie, 1985; Junaid, 1998; Rhea, 1995; Reinking & Alexander, 2005). In addition, the majority of prior studies of eating disorders have restricted their samples to female athletes (and non-athletes) at National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I universities.

This study’s purpose differed in that it involved an NCAA Division II university, where attitudes about eating were studied in relation to eating disorders in undergraduate female student-athletes and non-athletes. Relationships between eating disorders and a number of variables thought to contribute to eating disorders—self-esteem, body image, social pressures, and body mass index—were furthermore examined. The student-athletes at the mid-size institution in the Midwest were also queried to assess the prevalence of eating disorders among them based on sport played. Findings of the study can assist in developing and implementing appropriate eating-disorder prevention and intervention programs for female collegiate athletes.

Methods

Participants

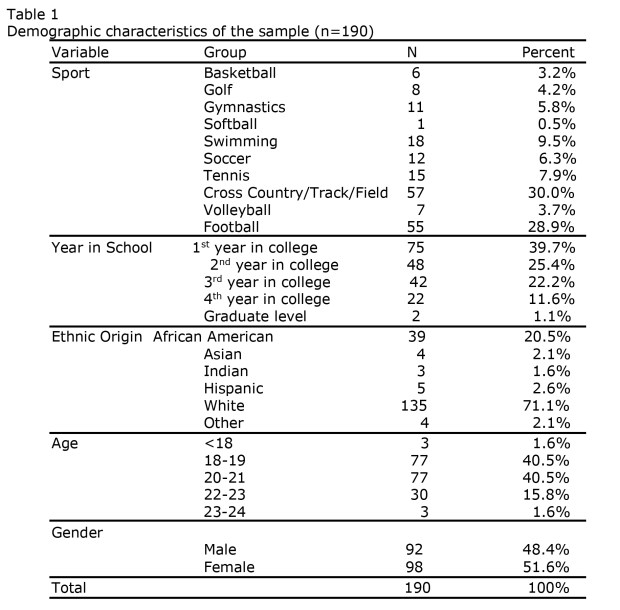

The participants (N = 125) in our study consisted of 60 female varsity student-athletes and 65 non-athlete students at a mid-size NCAA Division II Midwestern university. The mean age of participants was 20 years (SD = 4.3 years). The majority of participants, 93%, were Caucasian; 1% were African American; 1% were Native American; 3% were Asian American; and 2% were other. Of the student-athletes, 18.3% participated in softball (n = 11), 20% in soccer (n = 12), 13.3% in track (n = 8), 8.3% in cross-country (n = 5), 15% in basketball (n = 9), and 25% in volleyball (n = 15). Non-athlete participants were recruited from general psychology and wellness classes at the university. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and in accordance with university and federal guidelines for human subjects.

Instruments

Eating-disorder behaviors were assessed using the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT–26), which consists of 26 items and includes three factors: dieting; bulimia and food preoccupation; and oral control (Garner & Garfinkel, 1979; Garner, Olmsted, Bohr & Garfinkel, 1982). Respondents rate each item using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). This instrument has been used to study eating disorders in both a clinical and non-clinical population (Picard, 1999; Stephens, Schumaker, & Sibiya, 1999; Virnig & McLeod, 1996). It is a screening test that looks for actual or initiatory cases of anorexia and bulimia in both populations (Picard, 1999). The EAT–26 has demonstrated a high degree of internal reliability (Garner et al., 1982; Ginger & Kusum, 2001; Koslowsky et al., 1992). An individual’s EAT score is equal to the sum of all the coded responses. While scores can range from 0 to 78, individuals who score above 20 are strongly encouraged to take the results to a counselor, as it is possible they could be diagnosed with an eating disorder.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (1965) was modified and used to assess self-esteem in this study. Responses were chosen from a 4-point scale (1=strongly agree, 4=strongly disagree). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is a widely used measure of self-esteem that continues to be one of the best (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991). The scale has shown high reliability and validity (Furnham, Badmin, & Sneade, 2002).

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated (based on participants’ self-reported height and weight) as the ratio of weight (kg) to height squared (m2). Participants were categorized as underweight (BMI < 20.0), normal weight (20.0 < BMI < 25.0), overweight (25.0 < BMI < 30.0), or obese (30.0 < BMI) (National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 1998). Additionally, demographic information, body image, and social pressures were measured.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the university’s institutional review board, we requested and obtained permission from university athletic administrators, coaches, and class instructors to survey their female students, some of whom were student-athletes. We provided participants with an information sheet detailing the purpose of the study. We informed all the participants of their rights as human subjects prior to their completion of the survey, which took approximately 15 min. Because of the sensitive nature of the questions, participants were also informed that they could leave any questions unanswered and could discontinue participation at any time without penalty. The survey was administrated to non-athlete students during a class meeting. Female student-athletes completed the survey during their team meetings. All participants were assured anonymity because their names were not written on any individual questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS. An independent t test was used to determine if a difference existed in attitudes about eating held by female student-athletes and non-athlete students. To compare the prevalence of eating disorders among the student-athletes based on the sport played, analysis of variance was conducted with the data. Pearson product-moment correlations were computed to examine the relationship between eating disorders and variables that contribute to eating disorders. An alpha level of .05 was used to establish statistical significance.

Results

For each participant, an EAT–26 score was calculated using all 26 items. Using the 4-point clinical scoring, participants’ scores ranged from 0 to 46, with a mean score of 14.7 (SD = 5.9). Garner et al. (1982) have defined an EAT–26 score of 20 or above as indicating a likely clinical profile of an active eating disorder. In this study, the percentage of the participants who scored 20 or above on the EAT–26 was 8.8%. Among the student-athletes, 9.3% scored 20 or above, while the percentage of non-athletes with a 20 or above was 8.3%. An independent t test was conducted to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups. As shown in Table 2, although the average EAT–26 score for the non-athlete group was higher than that of the student-athletes, analysis revealed no significant difference between the groups: t (123) = -.589, p>.05.

Table 1

Participating Female Students’ Average Score on EAT–26

| Athletes (n = 60) M ± SD |

Non-Athletes (n = 65) M ± SD |

|

|---|---|---|

| EAT–26 Score |

15.4 ± 5.8 |

14 ± 5.0 |

Values are means ± SD; n, number of subjects

The second objective of the study was to compare the prevalence of eating disorders among female athletes based on sport played. As shown in Table 2, 18.2% of the surveyed student-athletes who played softball scored 20 or above on the EAT–26; 8.3% of the student-athletes who played soccer had scores of 20 or above. Participants who competed in track scored 20 or above in 12.5 % of cases; 6.7% of those who played volleyball scored 20 or above. None of the surveyed student-athletes who participated in cross-country or basketball scored as high as 20. However, analysis of the data in terms of sport played showed that the differences in average EAT-26 scores were not statistically significant.

Table 2

Results of Female Student-Athletes’ EAT–26 Scores, by Sport Played

| Frequency | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAT–26 Scores | Above 20 | Below 20 | Above 20 | Below 20 |

| Softball (n = 11) |

2918.281.8Soccer (n = 12)1118.391.7Track (n = 81712.587.5Cross-Country (n = 5) 5 100.0Basketball (n = 9) 9 100.0Volleyball (n = 15)1146.793.3

The mean body weight for all participants was 68.1±12.9 kg and mean BMI was 22.9±9.1. The mean desired body weight, in contrast, was 62.1±8.3 kg, while mean desired BMI was 20.9±5.2. On average, participants wanted to lose 6 kg. They reported desired weight changes ranging from a 69-lb loss to a 10-lb gain. The non-athlete group had a higher average current weight (69.1 kg) and a lower average desired weight (60.5 kg) than did the student-athletes, among whom average current weight was 66.6 kg and average desired weight was 63.6 kg. The calculations of BMI for the group as a whole showed 28% of them having a BMI of 25 or more, with 38% of the non-athletes recording a BMI of at least 25 or higher and 16% of student-athletes recording a BMI of 25 or higher.

When the participants were asked how self-conscious they are about their appearance, 30.4% said they were extremely self-conscious. However, when they were asked how they feel about their overall appearance, 3.2% said they were extremely dissatisfied, and only 17.6% said they were somewhat dissatisfied. This study found that 12% of the participants reportedly always feel social pressures from friends or family to maintain a certain body image; 53.6% reported sometimes feeling such pressure concerning body image. The results also showed that 1.6% of all participants rated their overall self-esteem as very low; 24% as low; 48.8% as neutral; 22.4% as high; and 3.2% as very high.

A Pearson product-moment correlation was conducted to look for a significant relationship between eating disorders and self-esteem, social pressures, body image, and participant’s BMI. No statistical significance was found between these variables and eating disorders.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine attitudes about eating in relation to eating disorders among female student-athletes and non-athletes in an NCAA Division II setting, to compare student-athletes’ rates of eating disorders based on sport played, and to examine the relationship between eating disorders and a number of variables believed to contribute to the development of disordered eating. Findings associated with the study’s first objective were not consistent with those of previous studies that found a higher percentage of eating disorders among student-athletes (Picard, 1999; Berry & Howe, 2000; McNulty et al., 2001). As to our second objective, our findings did not support earlier research suggesting that the prevalence of eating disorders among female athletes differs based on the sport played (Perriello, 2001; Picard, 1999). While the institution at which the present research was conducted had no gymnastics, dance, swimming, or cheerleading program, it did sponsor women’s track and cross-country programs. The present results for student-athletes in these two programs were not consistent with Picard’s and Perriello’s determination that track and cross-country athletes are more at risk of eating disorders than some other athletes. Findings related to the study’s third objective showed that any relationships between eating disorders and the variables self-esteem, social pressures, body image, and BMI were not statistically significant, contradicting earlier research on the development of eating disorders (Berry & Howe, 2000; Greenleaf, 2002). Some of the present findings may reflect differential exertion of pressure by coaches and teammates in institutions ranked Division II as opposed to Division I. Picard (1999) found demands to perform well to be stronger within Division I athletics, something that might be linked to a higher prevalence of eating disorders in Division I schools and athletic teams. However, more research needs to be done in this area.

This study was subject to several limitations. For example, it was conducted at the end of the academic year, timing that affected the number of participants available to complete the survey. Moreover, surveys were to be administered during class meetings, but because final examinations loomed, some instructors preferred not to take time from review to devote to the survey. In addition, with teams at or nearing the end of the competitive season, some seniors were no longer sport participants, making it difficult to administer surveys to an entire athletic team. Had the sample been larger, valid comparisons of student-athletes with non-athlete students, and of the student-athletes sport by sport, would have been more readily obtained. Conducting the study on a single Division II campus was a further limitation, related to the small sample size. Collecting data from all colleges in Division II of the NCAA would provide a greater range of individuals, both from the general student population and the population of student-athletes.

Growing numbers of workshops and presentations on eating disorders are being conducted on college campuses. Thanks to growing awareness of eating disorders, student-athletes are encouraged or even required to attend them. They learn what eating disorders are, some factors related to eating disorders, dangers posed by eating disorders, and treatment of eating disorders. Such knowledge better equips female student-athletes to avoid eating disorders.

The findings of the present study, in light of the literature in the field, suggest that future research should involve a larger segment of the NCAA Division II conference. A larger number of schools would not only create larger samples of athletes and non-athletes, it would also provide access to a wider variety of athletic teams. Another recommendation concerns timing of the survey administration. The EAT–26 should initially be completed by the two populations (student athletes, non-athlete students) at the beginning of the freshmen year and should be completed again at the end of that academic year. It would be interesting to know how many students began the freshmen year with no sign of an eating disorder, but, faced with the demands of study and pressures from friends, teammates, and coaches, became vulnerable to disordered eating.

References

Berry, T., & Howe, B. (2000). Risk factors for disordered eating in female university athletes. Journal of Sport Behavior, 23(3), 207–218.

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, K. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. W. Wrightsman (Eds.). Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 115–160). San Diego: Academic Press.

Carter, J. (2002). About 15 percent of major college athletes may have symptoms of eating disorders, study suggests. Retrieved December 21, 2006, from Ohio State University Web site: http://researchnews.osu.edu/archive/athlteat.htm

Davis, C., & Strachan, S. (2001). Elite female athletes with eating disorders: A study of psychopathological characteristics. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 23(3), 245–253.

Furnham, A., Badmin, N, & Sneade, I. (2002). Body image dissatisfaction: Gender differences in eating attitudes, self-esteem, and reasons for exercise. Journal of Psychology, 136(6), 581–596.

Garner, D. M., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1979). The Eating Attitudes Test: An index of symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 9, 273–279.

Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871–878.

Ginger, K., Kusum, S., & Hildy, G. (2001). Risk of eating disorders among female college athletes and nonathletes. Journal of College Counseling, 4(2), 122–32.

Greenleaf, C. (2002). Athletic body image: Exploratory interviews with former competitive female athletes. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 11(1), 63–88.

Griffin, J., & Berry, E. M. (2003). A modern day holy anorexia? Religious language in advertising and anorexia nervosa in the West. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57(1), 43–51.

Guthrie, S. (1985). The prevalence and development of eating disorders within a selected intercollegiate athlete population (anorexia nervosa, eating pathology, bulimia). Unpublished master’s thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus.

Hawes, K. (1999). Experts say eating disorders, diet and nutrition weigh heavy on scale of issues affecting college student-athletes. Retrieved December 12, 2006, from the National Collegiate Athletic Association Web site: http://www.ncaa.org/ news/1999/19991122/ active/3624n01.html

Hsu, G. L. (1990). Eating Disorders. New York: Guilford.

Irving, L. (1990). Mirror images: Effects of the standard of beauty on the self- and body-esteem of women exhibiting varying levels of bulimic symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9, 230–242.

Johnson, C., Powers, P. S., & Dick, R. (1999). Athletes and eating disorders: The National Collegiate Athletic Association study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 26, 179–188.

Junaid, S. (1998). An analysis of eating disorder correlates in female varsity athletes. MAI, 37(1), 63.

Levine, M. P., & Smolak, L. (1996). Media as a context for the development of disordered eating. In L. Smolak, M. P. Levine, & R. Striegel-Moore (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of eating disorders (pp. 183–204). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

McNulty, K., Adams, C., Anderson, J., & Affenito, S. (2001). Identifying eating disorders among athletes. Nutrition Research Newsletter, 20(9), 10.

National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (1998). First federal obesity clinical guidelines released. Retrieved March 22, 2007, from http://www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/bmicalc.htm

O’Connor, P., & Lewis, R. (1997). Physical and emotional problems of elite female gymnasts. New England Journal of Medicine, 336(2), 140–142.

Perriello, V. (2001). Aiming for healthy weight in wrestlers and other athletes. Contemporary Pediatrics. 18 (9), 55.

Picard, C. L. (1999). The level of competition as a factor for the development of eating disorders in female collegiate athletes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 583–594.

Rhea, D. (1995). Risk factors for the development of eating disorders in ethnically diverse high school athlete and non-athlete urban populations (Doctoral dissertation, Texas Christian University, 1995). Dissertation Abstracts International, 56(5A), 133.

Reinking, M. F. & Alexander, R.E. (2005). Prevalence of disordered-eating behaviors in undergraduate female collegiate athletes and non-athletes. Journal of Athletic Training, 40(1), 47–52.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sundgot-Borgen, J. (1994). Risk and trigger factors for the development of eating disorders in female elite athletes. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 26(4), 414–419.

Sundgot-Borgen, J., & Torstveit, M. K. (2004). Prevalence of eating disorders in elite athletes is higher than in the general population. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 14(1), 25–32.

Stephens, N., Schumaker, J., & Sibiya, T. (1999). Eating disorders and dieting behavior among Australian and Swazi university students. Journal of Social Psychology, 139(2), 153–158.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., Silberstein, L.R., & Rodin, J. (1986). Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. American Psychologist, 41, 246–263.

Thompson, R., & Sherman, R. T. (1999). Athletes, athletic performance, and eating disorders: Healthier alternatives. Journal of Social Issues, 55(2), 317–337.

Virnig, A. G., & McLeod, C. R. (1996). Attitudes toward eating and exercise: A comparison of runners and triathletes. Journal of Sport Behavior, 9(1), 82–90.

Worsnop, R. (1992). Eating Disorders, CQ Researcher, 2(47), 1097–1120.

Author Note

Nikki Smiley, Aberdeen (South Dakota) Family YMCA; Jon Lim, Department of Human Performance, Minnesota State University Mankato. Correspondence for this article should be addressed to Jon Lim, Ed.D., Coordinator & Assistant Professor,Sport Management Graduate and Undergraduate Programs, Minnesota State University, Mankato, 1400 Highland Center (HN 176), Mankato, MN 56001, 507-389-5231 Office Phone 507-389-5618. jon.lim@mnsu.edu