Submitted by: Josef Fahlén

Abstract

This paper reports on an analysis of individual perceptions of organizational structures in Swedish elite ice hockey with the purpose of studying the relationship with organizational position. Findings are based on structured interviews with 8 individuals who work or are volunteers in 4 different organizational positions in 2 elite ice hockey clubs. Organizational position is defined by hierarchical level, line or staff position, and by paid or volunteer position. Perceptions are studied in relation to the structural dimensions specialization, standardization, and centralization. Results show that perceptions are related to the organizational position occupied and that the various perceptions result in tensions between the different organizational positions. The results are discussed in relation to findings concerning organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

Increasing difficulties in attracting and retaining coaches, administrators and volunteers within Swedish sport (Peterson, 2002) has generated a growing interest in the management and design of sport organizations. Increasing demands for effectiveness have increased the need for more sophisticated organizational structures which in turn have resulted in new, changed, and unknown circumstances for the people involved in sport organizations (Amis, Slack & Berrett, 1995). During these circumstances individual perceptions of organizational structures becomes important to explore.

In the study of organizations, the concept of organizational structure and the structural dimensions specialization, standardization and centralization has long been utilized to describe organizational features and configurations (Hage & Aiken, 1967; Lawrence & Lorch, 1967, Pugh et al., 1968; and Thompson, 1967). The concept of organizational structure has also been studied in relationship to individual variables such as organizational commitment, job satisfaction, job performance, employee turnover etc (see Porter & Lawler; 1964 and Cumming & Berger, 1976 for early reviews).

This text takes its departure in Fahlén (n.d.) where perceptions of organizational structure in two structurally different ice hockey clubs were compared. That study showed, amongst other things, that high levels of the three structural dimensions -specialization, standardization and centralization- were perceived more positively than low levels. The study did however not distinguish between different positions in each organization and as e.g. Payne and Mansfield (1973) point out, representing organizational climate in terms of mean values can be misleading. Payne and Mansfield (1973) showed that people in different positions in an organization have different views about the organizational climate. Rice and Mitchell (1973) have also shown that an individual’s perceptions are related to his or her position within an organization. Thus, studying individual perceptions related to organizational position becomes interesting.

Studying individual perceptions of organizational structure will not only help us to understand some of the mechanisms behind attracting and retaining individuals in a voluntary sport organization but will also contribute to the broader literature on both organizational structure and organizational commitment, organizational climate, job satisfaction, job performance, employee turnover etc.. Since organizations are much too complex for any given variable to have a consistent unidirectional effect across a wide variety of types of conditions (Porter & Lawler, 1965) extending the analysis to the study of variation in perceptions between different positions within an organization will help us broaden our understanding of how organizational structure affects individuals. If voluntary sport organizations are to succeed in delivering programs and events, the reasons behind individual perceptions and behaviors need to be explored. Organizations which fail to attract and retain a voluntary or paid workforce are more likely to spend more time and effort recruiting and training new personnel than furthering the goals of the organization (Cuskelly, 1995).

The purpose of this paper is to examine the relationship between the positions of individuals in an organization and their perceptions of organizational structures. The aim is not to seek incontrovertible proof of cause and effect relationships between organizational structure and individual perceptions but to, in an explorative manor, throw light upon some mechanisms behind mentioned perceptions. The analysis is based on interview data from two elite ice hockey clubs in Sweden.

Theoretical background

In the literature pertaining to the study of organizations it has long been emphasized that research needs to bridge the traditional gap between macro and micro, between the total organization, the group, and the individual (Brass, 1981). While considerable effort has been devoted to both the structures of organizations and to individual attitudes to work less attention has been given the relationship between the two. The relationship has indeed been investigated but, with a few exceptions (e.g. Oldham & Hackman, 1981; Pheysey, Payne & Pugh, 1971), exactly how it functions remains unexplored. What we do know about attitudes towards and perceptions of structural features is based mainly on results taken from industrial and government enterprises and we do not yet know whether that knowledge would hold in a sport organization context (Chang & Chelladurai, 2003).

Research roughly speaking has studied either individual or organizational factors as possible sources of individual perceptions such as e.g. job satisfaction or organizational commitment. Both perspectives have produced results to support their case even if some comparative studies have found perceptions, attitudes and behaviors to be related more to the structural context within which the job occurs than to individual characteristics (e.g. Glisson & Durick, 1988; Oldham & Hackman, 1981).

The basic assumption in this paper is drawn from the Job-Modification Framework where an understanding of the relationship between organizational structure and individuals’ perceptions is sought by looking at structural context and more precisely the characteristics of the job. Organizational structure is seen to affect job characteristics which in turn affect individual perceptions of the work and the organization. The Job-Modification Framework is based on findings concerning the relationship between organizational structure and job characteristics (e.g. Pheysey, Payne & Pugh, 1971) and on the relationship between job characteristics and individual perceptions (e.g. Pierce & Dunham, 1978). Theoretical and empirical work using the Job-Modification Framework offer some understanding of how organizational structure is perceived by individuals in an organization (e.g. Rousseau, 1977; and Oldham & Hackman, 1981).

One significant characteristic of a job is its position within an organization (Rice & Mitchell, 1973). Both hierarchical position and line or staff position have been explored in the literature. In the study of sport organizations the distinction between paid staff and volunteer personnel has also been analyzed. Research into organizational position with regard to the distinction hierarchical level and line or staff function has, broadly speaking, shown that people at higher levels and in line positions are to a greater extent associated with more positive attitudes, such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and with more positive behaviors such as high performance and low absenteeism (Cummings & Berger, 1976; and Porter & Lawler, 1964). No uniform findings regarding the differences between people in paid and volunteer positions are available but some related research shows that the two groups have different perceptions of e.g. organizational commitment and influence in decision making (Cuskelly, Boag & McIntyre, 1999; Auld & Godbey, 1998; and Cuskelly, McIntyre & Boag, 1998).

Using the framework proposed above and supporting empirical findings on the job characteristics mentioned will allow an exploration of and explanations for possible differences in individual perceptions of organizational structure in this study. No causal interpretations of possible relationships will be made since neither sample nor method is appropriate for testing. Nevertheless the findings may be useful in pointing out where further research on sport organizations is needed, how knowledge of these issues can be achieved, and why this knowledge is important for the management of sport organizations in Sweden and elsewhere.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected in two Swedish elite ice hockey clubs, clubs organized along lines similar to those in many industrialized countries today. The sporting individual is a member of a sport club, which in turn is affiliated to a regional sport federation, which in turn is affiliated to a national sport federation under the Swedish sports confederation (RF). The Swedish elite ice hockey league is the highest division in a system comprising a maximum of seven divisions. The system is hierarchical based on sports merits and the teams are run by membership-based non-profit clubs.

One way of moving away from calculated means and closer to actual perceptions is to analyze interview data from individuals in a variety of positions within an organization. The definition of organizational position, inspired by the Aston Paradigm, comprises the distinction between hierarchical levels (Pugh et al., 1968), the distinction between line and staff personnel as proposed by Porter and Lawler (1965), and the distinction between paid staff and volunteer personnel. No distinction is made between the two clubs.

The lowest hierarchical level (0) according to Pugh, et al. (1968) is the operating level, the direct worker, in this case assumed to be the ice hockey player or the Youth volunteer. Line personnel are the people involved in the organization’s primary output (playing ice hockey) while staff personnel are involved in the coordination, control, and support of those in line positions. Paid staff derive their main income from the organization. Volunteer personnel, while not excluded if paid smaller amounts, are not salaried in the sense that they make their living from their involvement.

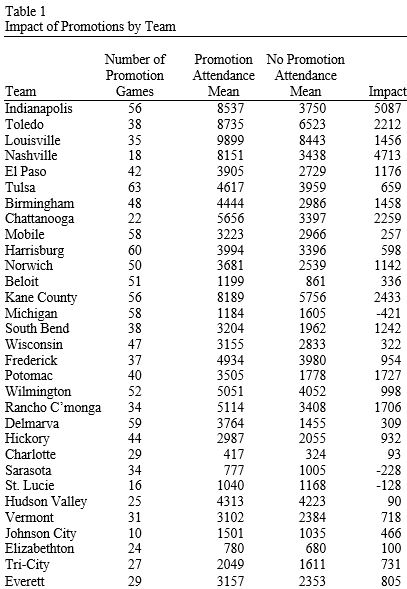

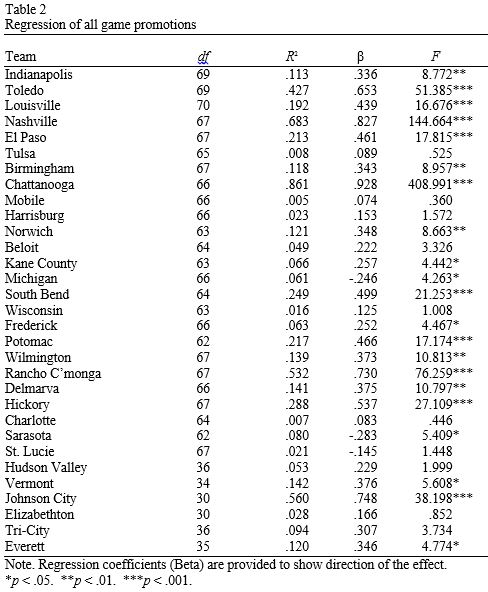

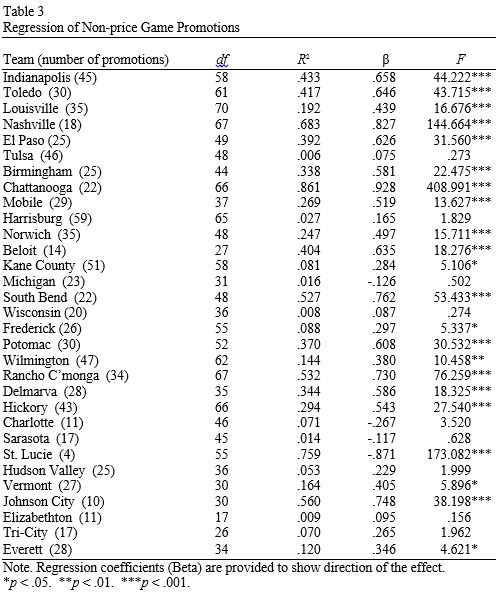

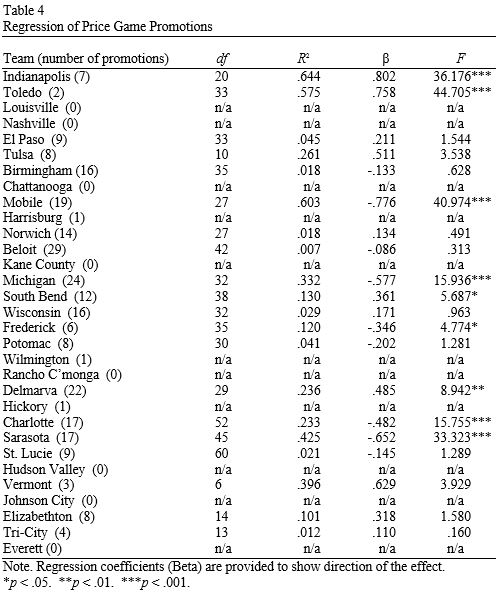

Respondents were picked based on organizational position. My aim was to reach individuals on all levels, in both line and staff positions, and both paid staff and volunteer personnel. For those positions where there was more than one individual to choose from interviewees were selected in consultation with the general manager based on accessibility. The selection resulted in 4 interviewees from each club as shown in Table 1: member of the board, coach of the first team, sales manager, and volunteer in the youth program.

Table 1

Organizational Position

| Rank Above Lowest Level |

Staff Positions |

Line Positions |

| Voluntary Position |

Paid Position |

Paid Position |

Voluntary Position |

| 3 |

Board Member |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

Sales Manager |

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

Coach First Team |

|

| 0 |

|

|

|

Youth Volunteer |

Measures

Inspired by the constructs created by Kikulis, Slack, Hinings and Zimmerman (1989) and Slack and Hinings (1987) a list of interview questions was created that were considered to reflect the three structural dimensions of organizational structure. With a minor modification to the Interview Questions, Organization Design Index (Slack, n.d.) it was possible to adjust the constructs and the questions to fit this particular study.

The concept of specialization was operationalized using questions regarding the extent of the administrative and operative roles together with the division between these. The operationalization of specialization involved questions regarding the number of paid staff versus volunteers and the division of tasks between the two groups (Slack & Hinings, 1992).

The operationalization of standardization involved questions about efforts made to reduce variations in procedures and to promote coordination. These questions were intended to examine how and to what extent activities are governed and regulated by rules, policies and other formal procedures (Slack & Hinings, 1992).

The centralization concept was operationalized through questions regarding where decisions are made and how the decision making is distributed. Centralization was examined in three ways; at which hierarchical level the decisions were made, the extent of participation in decision making on other hierarchical levels, and the involvement of volunteers in the decision-making process (Slack & Hinings, 1992).

No measure of organizational structure other than each interviewee’s perception was used. Contrary to e.g. Oldman and Hackman (1981) where the president or someone similar provided data on organizational structures for the employees to relate to, the present study assumes organizational structure to be partly a function of the perceptions of the organizational members in question. Inherent in the notion of organizational position, as presented earlier, is an assumption that perceptions of organizational structure are affected by an individual’s place in the organizational hierarchy, distance from the core activities, and function as either paid staff or volunteer personnel. It follows with this line of argument that organizational structure is not seen as a constant variable for the interviewees to relate to but as a perceptual concept constructed by each interviewee.

Perceptions of organizational structure were not measured in the way commonly used in the literature on job satisfaction and organizational climate such as job challenge (Payne & Mansfield, 1973), autonomy (Hackman & Oldham, 1975), feedback (Brass, 1981) and similar. Instead, interviewees were asked to speak freely about organizational structures.

Procedure

The interview questions were designed to study (a) the picture each interviewee had of the respective club’s structural arrangements, (b) each interviewee’s opinion about those same structural arrangements, and (c) how each interviewee were affected by those arrangements. This procedure made it possible to explore both links in the Job-Modification Framework, (1) the relationship between organizational structure and job characteristics and (2) the relationship between job characteristics and individual perceptions. It also allowed for organizational structures to having a direct effect on individual perceptions regardless of any relationships they might have with job characteristics (cf. Brass, 1981).

The structured interviews, lasting approximately one hour, were conducted face to face in each interviewee’s workplace, in private. The interviews were recorded, transcribed in full and then coded for anonymity. Interview data were analyzed using the techniques outlined by Stake (1995).

Results

The results are presented according to organizational position with regard to hierarchical position, the distinction of line or staff, paid or volunteer, as shown in Table 1. The quotations should be read as examples and illustrations of the opinions found in the data rather than complete reflections of all opinions. Quotations are taken from both respondents in each position without any given order.

The Board Member Position on Specialization

I have worked to move the daily operations down to the office. The club has gotten to large to for [us] voluntary forces to run the daily and operative business. I want the financial committee to function more as a sounding board for XX and YY [two individuals working in paid staff positions] who need to take the day-to-day responsibility.

The Board Member Position on Standardization

First of all, you need to have your heart in the club and be interested in ice hockey..In my position I think it is good to have [a degree in business administration]. Issues like balancing the books or discussing things with accountants would be difficult otherwise ..The general level of expertise needs to be raised.

Documented routines are important..I do not see them as paper tigers, I see them as documents that are observed..Who should authorize payments, orders, investments..We try to do things in a corporate way even if we are a club.

The Board Member Position on Centralization

There is always some friction between the employees and the board, everywhere and in all kinds of issues..If this were a company it would be easy, but now it is kind of both you could say..Volunteers against professional staff.of course there is friction in between.

The sport committee is the centre of gravity in the club.handles sports-related issues.[which are] the most important issues.decides on new recruitments [players] and lay-offs.

The Sales Manager Position on Specialization

There should be more people [working at the office], so that each one could focus on his task so to say..You might want a board that works closer to the actual operations..They have more of a supervisory role [now]..We need more people working [administrative] with our youth operations..They have grown too big for one person to handle.

Everything has to go through us [the office].the youth teams can not go around selling advertisements on their own.

The Sales Manager Position on Standardization

There are always courses and classes for all kinds of things but here we try to learn from each other instead..Education and those things are important but I would go according to background and personality more than education..You cannot just go for a theorist with so and so many [academic] credits..It is more to do with relations.

The club has produced a handbook for the operations.fairly detailed as to what we can do and can not do.which issues go up to the board and such..All the way from the youngest youth team.not only on the ice but also journeys, cups and such. It is a must in such a large club as this..In that way we can avoid all questions and rumors in the corridors.just look it up in the book.

The Sales Manager Position on Centralization

You might want some more steering and concrete ideas [from the board]..One shortcoming, in my opinion, is that the board is quicker to question our work than to give us directions..It is very seldom we get concrete assignments. Instead it is us generating proposals and ideas. It ought to be the other way around more often.

More things need to go through us.we cannot leave the decisions to the dads and mums.there are a lot of capable people but you feel that you cannot let things go..Same goes for transports as for away games and team uniforms..More control is needed.

The Coach of the First Team Position on Specialization

My opinion is that the sport manager should have both the competence and power to direct the sport issues..Not as it is now with ideas coming from down here and up..It is problematic to have us [head coach and assistant coach] doing everything..We should be let to focus on our jobs.

The Coach of the First Team Position on Standardization

We must keep ourselves updated. The problem is lack of time..Coaching at top-level leaves little time for education..Of course competence is important but I think you need to calculate from case to case whether courses, degrees, or experience is to be preferred..But you have to adhere to the standards [set by the Swedish Ice Hockey Association (SIF)].

Not everything is written down, it is more like the players know these things..As long as they take care of things there are no problems..It is tacit and unspoken..It is often solved within the group..Policies and routines are important but most important is having strong individuals supporting [the policies and the routines].

The Coach of the First Team Position on Centralization

When it comes to hockey I have all the authority I want.training, organizing traveling, pre-season, cups etc..Outside hockey, very limited..You can have ideas and, for instance, shopping lists for players but when you don’t know all the financial stuff it is problematic..I would like to know the [players’] salaries so that I could evaluate from that.

The sport committee evaluates [the team] during the season.but they do not have the same basis for making decisions as me and ZZ [the assistant coach] have..If I want to get rid of a player it is often impossible since they are bound by contracts.[then] you just have to put up with it.[but] it is not unusual for us to get the blame for it [a less successful recruitment].

The Volunteer in the Youth Program Position on Specialization

I think all sport clubs with a first team in the premier division would benefit from separating the youth and the elite operations..Run the elite operations on business lines.and let the youth operations lead their own life..It is all business [otherwise]..Making ends meet in the youth operations is no problem.

The Volunteer in the Youth Program Position on Standardization

We generally start with the parents.with some kind of interest and/or know-how. After one year we send them to Step 1 [Basic Youth Leader Course at SIF].which is a requirement [if they want to continue].next year Step 2 and so on..It is important for us to educate both kids and parents..How [else] are we supposed to foster our own elite coaches?

I personally think that it is good that the club has policies.so that everybody pulls together..Do the right thing at different ages, when to send in the best players etc..I think it is really important for the club’s survival..We have rules for how to practice and play.but more importantly we have policies for behavior and what it means to play ice hockey.do you best.

The Volunteer in the Youth Program Position on Centralization

We [the youth operations] apply for money each season [from the board]..They set the budget.and we manage ourselves..The board is 98 percent concerned with issues related to the first team and the juniors [Team 18 and Team 20].they trust us to do the best we can.

This club is based on mutual trust…when it comes to money, education, tasks.I need to trust that he or she is doing their best.I have enough to do doing my own job.

Discussion

This study has examined the relationship between the positions of individuals in an organization and their perceptions of organizational structures. Organizational position was defined by hierarchical level, line or staff position, and by paid or volunteer position. This discussion will show how an individual’s organizational position relates to their perceptions of the structural dimensions specialization, standardization and centralization. On a few occasions, quotations in the Results above overlap into two or more of the analytical paragraphs below.

High vs. low hierarchical positions

Specialization

People in all positions express a feeling of working to capacity and would rather see someone else doing more. The statements from the interviewees indicate that people in high positions transfer responsibility and tasks downwards and people in low positions refer responsibility and tasks upwards in the organization.

Explaining these findings by means of hierarchical position seems to be difficult but a few pointers can be found in Cumming and Berger (1976) where Meta study results show that people in higher positions derive satisfaction, among other things, from smoothness of workflow while people in lower positions derive satisfaction, among other things, from the amount of work they do. It seems that directing tasks elsewhere might help both groups achieve satisfaction, for people in lower positions as it reduces their workload and for people in higher positions as it makes the workflow smoother.

People in higher positions are argued to be more satisfied with their job than people in lower positions are (Herrera & Lim, 2003). The results in present study however provide no indications to support that view.

Standardization

Formal education and formal competence is more important at the top and at the bottom of the organization, and is seen in both places as a requirement for the work. At middle levels background, personality and experience are seen as more valuable than formal qualifications.

Standardization, formal structuring, routines, procedures and management practices are often said to be associated with job satisfaction (e.g. Stevens, Philipsen, & Diederiks, 1992). Educational level is also found to be related to job satisfaction, with high educational levels related to high satisfaction levels (Herrera & Lim, 2003). None of these findings however shed any light on the differing perceptions in this study.

Centralization

People in higher positions express a need to control the activities of people in positions further down in the organization, while the people in lower positions refer to the need for mutual trust. It seems, however, as if the trust mostly works one way – upwards.

The need for control as expressed by people in higher positions can be understood with reference to the findings in Rice and Mitchell (1973) where people in higher positions are found to attach greater importance to external results (turnover, profit, on-ice success and such) than people in lower positions. The reason for this could be found in Inglis (1994) where higher visibility is given as a reason for differences between professionals and volunteers. Likewise, visibility could offer one possible explanation of why people in higher positions are concerned with controlling the activities of people in lower positions. The higher visibility means that the people in higher positions are more strongly associated with the success or failure of the organization, making the need for control understandable.

Another possible explanation could be sought in organizational commitment where Jackson and Williams (1981) have found that higher positions are more positively related to organizational commitment than lower levels are. This commitment in the present study could be illustrated by the greater need for control.

Line vs. staff positions

Specialization

Differences in opinions regarding specialization between line and staff personnel are not easily separated from differences related to the distinctions paid or volunteer positions and high or low positions. There are nevertheless some expressions which indicate that both groups would like to focus on their “own” tasks, even if some people in staff positions would also like to have some supervision over some of the tasks performed by people in line positions.

It is argued that people in staff positions derive less satisfaction from their jobs than people in line positions (Porter & Lawler, 1965). The results in this study, however, provide no support for more or less satisfaction in either group.

Standardization

The main difference in perceptions concerning standardization between the people in line and the people in staff positions is how the two groups see the time dimension in formal education and training. The interviewees in line positions talk in terms of continuous training and education during their current appointment while the interviewees in staff positions refer to the level of competence demanded for their respective appointments. In simple terms, line personnel expect training and education on the job while staff personnel expect to have achieved the level of competence required before they take up an appointment.

One possible understanding of this difference is pointed out in Fahlén (n.d.) where historical and cultural reasons are given as explanations of differences in attitudes towards formal education. Sport in Sweden has traditionally, until very recently, been managed solely by volunteers and training and education, where it existed, was delivered by each respective national sport federation with a strict focus on practical coaching (Blom & Lindroth, 1995; Fahlström, 2001). This could have resulted in certain expectations among individuals involved in practical coaching and other expectations with individuals involved in supporting positions.

Centralization

Comparing the opinions on the locus of control between the board member position and the coach position gives us some insight into the power struggle between line and staff personnel. The sport committee, consisting mainly of board members, is seen by the board members as the main decision maker when it comes to the recruitment and laying off of players. The coach position, on the other hand, hints that the true decision lies with him and his assistant coach but admits that decisions in the sport committee which is beyond his influence throw spanners in the works. It is obvious where the coach position thinks the power should be.

One possible explanation for these differing perceptions could be a conflict between two functions stemming from the clash between two different sources of power. People in staff positions might derive their power primarily from the fact that they perceive themselves as being in charge of acquisition and the control of resources and thus important for the success of the organization and thereby powerful. Similarly people in line positions might perceive themselves as being very central to the organization in terms of being the people who know the game and who should therefore be in charge (cf. Slack, Berrett & Mistry, 1994).

Paid vs. volunteer positions

Specialization

Both paid and volunteer personnel are fairly unanimous that the other group should do more. The division of tasks, however, between the two does not seem to be all that simple. The paid personnel, perhaps empowered by their salary and their longer hours, seem to think that keeping and/or moving tasks to the office implies a guarantee of quality. Both groups however agree on the need for more paid staff in order to cope with the heavy workload.

Cuskelly, McIntyre and Boag (1998) found similar results where volunteers feel marginalized by the paid staff and paid staff feel frustrated with the volunteers not meeting their deadlines and not doing their jobs. The two groups seem irreconcilable but Farrell, Johnston and Twynam (1998) argue that it is the responsibility of the management to manage facilities and operations in a way that satisfies volunteers in order to make them stay. However that may be it seems that communication and task definition need to be addressed. The easy way would, of course, be to engage more people for both functions, a solution which, needless to say, is easier said than achieved.

It should however be noted that earlier findings have shown that commitment to an organization decreases inversely with level of remuneration and also inversely with number of working hours (Chang & Chelladurai, 2003).

Standardization

Differences in opinions on standardization between paid and volunteer personnel are not so easy to discern. All positions apart from the coach of the first team position express the importance of routines, guidelines, rules, handbooks etc. The coach position on the other hand refers to traditions, tacit and unspoken knowledge, and group norms. It would take further investigation to reach an understanding of why perceptions within the paid positions differ.

Centralization

Not only is the division of tasks a source of conflict between paid and volunteer personnel but perhaps even more evident is the division in opinions about where decisions should be made. The volunteers in the youth operations want to mind on their own business whereas the people in the office cannot accept decision making being in the hands of parents.

This finding conflicts with some findings in Auld and Godbey (1998) where both professionals and volunteers agree that professionals have more influence over decision-making. Both groups also agree that the relationship should be more balanced, the professionals even more than the volunteers. The commitment to voluntary governance is stronger among professional staff than volunteers. The professionals want the involvement of experienced volunteers with more insight and knowledge about the particular sport. As a comment on these disparities Cuskelly, Boag and McIntyre (1999) argue that it seems that the opinions and behavior of volunteers do not integrate into the explanatory system of organizational behavior as easily as those of employees do.

One possible explanation for the differing perceptions can however be found in the findings of Amis, Slack and Berrett (1995) where the professionals’ need for control is explained by financial dependence. Since professionals are dependent on the success of the organization for their own financial wellbeing their need for control is assumed to be greater.

Conclusion

The present analysis can offer a few pointers on how organizational structure is perceived by individuals in a sport organization and how their organizational position is related to these perceptions. In these conclusions I will also try to elaborate on the implications these perceptions may have for the development of these organizations..

Regarding the structural dimension specialization most people would like somebody else to do more, making their own focus narrower. The indications are the same, whether you compare high and low, line and staff, or paid and volunteer positions. The exception is the people in paid staff positions at the upper middle level who would like to keep more tasks in the office, as they put it. It would seem that the organization is perhaps too thin around the middle, needing more people on the upper middle level to carry out managerial and administrative duties.

Perceptions of standardization show that formal education is seen as being more important at the top and at the bottom of the organization and that people in staff positions see formal education as a prerequisite while people in line positions see training and education as a part of their job. It would seem that prospective educational measures should be directed towards the upper middle hierarchical level, or simply that formal education is not needed to the same extent at that level. Another possible implication is that there should be an attempt to raise the requirement for formal education among people in line positions and to extend on-the-job training and education among people in staff positions. Why routines, guidelines, rules, handbooks etc. are considered less important by people in paid line positions at the lower middle level than by the rest of the interviewees remains to be explored. It might be implied, however, that the operations around the first team are dependent on the specific person in the position at the time rather than on the performance of the organization.

Centralization of control and decision making is where the differences in perceptions are most obvious. All groups want to have control over decisions concerning their own tasks but people in high, staff, and paid positions would also like to have control over people in low, line, and volunteer positions. The implications of this seem to be that decision making, control, and power are moving from volunteer board members to paid administrators, away from the actual line operations to the staff positions, and from both high and low levels to the upper middle level of an organization. Auld and Godbey (1998) have however shown that balance, between paid staff and volunteers, regarding control, power, and decision making is not necessarily needed in order for an organization to be successful.

The extension of these findings and their contribution to our knowledge on the interplay between organizations and individuals in general and sport organizations more specifically is primarily that organizational structure affects individuals within an organization and that organizational position is related to the perceptions these individuals express.

Secondly, this study has shown how the distinctions high and low, line and staff, and paid and volunteer can be used to define organizational position and how the concept of organizational position could be used in illustrating how different positions in an organization relate to each other and to internal and external influences, pressures and phenomena.

Finally, these results can be used to gain an understanding of some of the reasons behind personnel (primarily volunteers) turnover in sport organizations and what the organization in question could do about this. While it is already recognized that volunteers are indispensable to both Swedish and international sport not much effort has so far been spent on finding out how they can be attracted and retained.

Even if organizational factors have been found to be more important than individual ones in other studies (Cuskelly, 1995), generalizations from this study should be made with care. Since such a small and specific sample as the one used in this study is sensitive to such variables as age, gender and income and not just to hierarchical position, line or staff function, or paid or volunteer position (cf. Ebeling, King & Rogers, 1979). The linear relationships assumed on a few occasions in this text should also be read critically. Even if earlier findings have shown results at one end of the scale it is not always correct to assume the opposite results at the other end of the scale (cf. Porter & Lawler, 1965). Similarly it is hard to tell separate and combined effects apart. While some perceptions can be the result of one organizational distinction others can certainly be result of two or three.

References

- Amis, J., Slack, T., & Berrett, T., (1995). The structural antecedents of conflict in voluntary sport organizations. Leisure Studies, 14, 1-16.

- Auld, C.J., & Godbey, G. (1998). Influence in Canadian National Sport Organizations: perceptions of professionals and volunteers. Journal of sport management, 12, 20-38.

- Blom, K. A., & Lindroth, J. (1995). Idrottens historia [The history of sport]. Malmö: Utbildningsproduktion AB.

- Brass, D.J. (1981). Structural Relationships, Job Characteristics, and Worker Satisfaction and Performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 331-348.

- Chang, K., & Chelladurai, P. (2003). Comparison of part-time workers and full-time workers: Commitment and citizenship behaviors in Korean sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 17, 394-416.

- Cummings, L.L., & Berger, C.J. (1976). Organization Structure: How Does It Influence Attitudes and Performance? Organizational Dynamics, 5, 34-49.

- Cuskelly, G. (1995). The influence of committee functioning on the organizational commitment of volunteer administrators in sport. Journal of Sport Behavior, 18, 254-270.

- Cuskelly, G., Boag, A., & McIntyre, N. (1999). Differences in organizational commitment between paid and volunteer administrators in sport. European Journal for Sport Management, 6, 39-61.

- Cuskelly, G., McIntyre, N., & Boag, A. (1998). A Longitudinal Study of the Development of Organizational Commitment amongst Volunteer Sport Administrators. Journal of Sport Management, 12, 181-202.

- Ebeling, J.S., King, M, & Rogers, M. (1979). Organizational Hierarchy and Work Satisfaction: New Findings Using National Survey Data. Human Relations, 32, 567-589.

- Fahlén, J. (n.d). Organizational Structures – Perceived Consequences for Professionals and Volunteers: A Comparative Study of Two Swedish Elite Ice Hockey Clubs. Unpublished manuscript. Umeå: Umeå Universitet.

- Fahlström, P.G. (2001). Ishockeycoacher: En studie om rekrytering, arbete och ledarstil [Ice hockey coaches: A study on recruiting, work and leadership style}]. Umeå: Umeå Universitet.

- Farrell, J.M., Johnston, M.E., & Twynam, G.D. (1998). Volunteer Motivation, Satisfaction and Management at an Elite Sporting Competition. Journal of Sport Management, 12, 288-300.

- Glisson, C. & Durick, M. (1988). Predictors of Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Human Service Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 61-81.

- Hackman, J.R., & Oldham, G.R. (1975). Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 159-170.

- Hage, J., & Aiken, M. (1967). Program change and organizational properties: a comparative analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 72, 503-519.

- Herrera, R., & Lim, J.Y. (2003). Job satisfaction among athletic trainers in NCAA division Iaa institutions. The Sport Journal, 6.

- Inglis, S. (1994). Exploring volunteer board member and executive director needs: Importance and fulfillment. Journal of Applied Recreation Research, 19, 171-189.

- Jackson, J.J., & Williams, T. (1981). Involvement in a voluntary sport organization. Journal of Sport Behavior, 4, 45-53.

- Kikulis, L., Slack, T., Hinings, B., & Zimmerman, A. (1989). A structural taxonomy of amateur sport organizations. Journal of sport management, 3, 129-150.

- Lawrence, P.R., & Lorch, J.W. (1967). Organization and Environment. Boston: Harvard University, Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration.

- Oldham, G.R., & Hackman, J.R. (1981). Relationships Between Organizational Structure and Employee Reactions: Comparing Alternative Frameworks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 66-83.

- Payne, R.L., & Mansfield, R. (1973). Relationships of Perceptions of Organizational Climate to Organizational Structure, Context, and Hierarchical Position. Administrative Science Quarterly, 18, 515-526.

- Peterson, T. (2002). En allt allvarligare lek. Om idrottsrörelsens partiella kommersialisering 1967-2002 [An ever more serious game. About the partial commercialization of the sports movement 1967-2002]. In Lindroth, J., & Norberg, J. (Eds.), Ett idrottssekel: Riksidrottsförbundet 1903-2003 (pp. 397-410). Stockholm: Informationsförlaget.

- Pheysey, D.C., Payne, R.L., & Pugh, D.S. (1971). Influence of structure at organizational and group levels. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16, 61-73.

- Pierce, J.L., & Dunham, R.B. (1978). An empirical demonstration of the convergence of common macro- and micro-organization measures. Academy of Management Journal, 21, 410-418.

- Porter, L.W., & Lawler, E.E. (1964). The effects of tall vs. flat organization structures on managerial job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 17, 135-148.

- Porter, L.W., & Lawler, E.E. (1965). Properties of organization structure in relation to job attitudes and job behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 64, 23-51.

- Pugh, D.S., Hickson, D.J., Hinings, C.R., & Turner, C. (1968). Dimensions of organizational structure. Administrative Science Quarterly, 13, 65-105.

- Rice, L.E., & Mitchell, T.R. (1973). Structural Determinants of Individual Behavior in Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 18, 56-70.

- Rousseau, D.M. (1977). Technological differences in job characteristics, employee satisfaction and motivation.: A synthesis of job design research and sociotechnical systems theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 19, 18-42.

- Slack, T. (n.d.). Interview questions organization design index. Unpublished manuscript, University of Alberta, Faculty of Education and Recreation.

- Slack, T., Berrett, T, & Mistry, K. (1994). Rational planning systems as a source of organizational conflict. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 29, 317-328.

- Slack, T., & Hinings, B. (1987). Planning and organizational change: A conceptual framework for the analysis of amateur sport organizations. Canadian Journal of Sport Sciences, 12, 185-193.

- Slack, T., & Hinings, C.R. (1992). Understanding change in national sport organizations: An integration of theoretical perspectives. Journal of Sport Management, 6, 114-132.

- Stake, R.E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Stevens, F., Philipsen, H., & Diederiks, J. (1992). Organizational and Professional Prediction of Physician Satisfaction. Organization Studies, 13, 35-49.

- Thompson, J.D. (1967). Organizations in action. New York: McGraw-Hill.