The Study of Physiological Factors and Performance in Welterweight Taekwondo Athletes

Abstract

The purpose of this research was to investigate the variation in heart rate, oxygen consumption and blood lactic acid for taekwondo athletes during training and competition. Ten taekwondo athletes from a Division I university volunteered for the research. The average age of the subjects was 19.5±0.5 .4 yr, the height was 174.6±2.8 cm, the weight was 63.6±1.4 kg, the black belt rank was 2.5±0.5, and the average training period was 6.4±1.0 years. The competition was of university class. During the experiment, each subject rode the bicycle ergometer until complete exhaustion at a speed of 60 RPM and power of 120W that increased by 30W every two minutes. The investigation focused mainly on the variations during the rest period and the three recovery periods after exercise (5th, 30th and 60th minute). Wireless heart recorder (POLAR), Vmax29 gas analyzer, YSI2300 lactic acid analyzer and DAIICHI analyzer were used to analyze heart rate, oxygen consumption, blood lactic acid and urobilinogen. According to the statistical analysis on one-way ANOVA with Repeated Measures and a Scheffe Post Hoc test, the results showed that:

1.There was no difference at the cardiac respiratory functioning between training and competition period. The players can’t recovery quickly for sixty minutes.

2. There was a significant difference at the BLA on the competition period higher than training period (7.0±1.3 vs. 6.3±1.2 mmol/l, p<.05).

3.There was no difference at the URO between training and competition period in the post-exercise 60 minute and rest.4. There was a difference on the output power at training period higher than competition period (232.7±14.5 vs. 226.5±14.7 watt, p< .05).

To recover the rest state more time and improve intensive training in the blood lactic acid system and power output. It’s a benefit and helpful for the players and coaches to investigate the reference during the contest and sport science training.

I. Introduction

According to the theory of Periodization of Strength, gains in muscular strength (M*S) during the M*S phase should be transformed into either muscular endurance (M-E) or P during the conversion phase so athletes acquire the best possible sport-specific strength and are equipped with the physiological capabilities necessary for good performance during the competitive phase. To maintain good performance throughout the competitive phase, this physiological base must be maintained (Bompa, 1999). The determination of physiological variables such as the anaerobic threshold (AT) and maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) through incremental exercise testing, and relevance of these variables to endurance performance, is a major requirement for coaches and athletes (Bentley, Mcnaughton, Thompson, & Batterhan, 2001).

According to the theory of Periodization of Strength, gains in muscular strength (M*S) during the M*S phase should be transformed into either muscular endurance (M-E) or P during the conversion phase so athletes acquire the best possible sport-specific strength and are equipped with the physiological capabilities necessary for good performance during the competitive phase. To maintain good performance throughout the competitive phase, this physiological base must be maintained (Bompa, 1999). The determination of physiological variables such as the anaerobic threshold (AT) and maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) through incremental exercise testing, and relevance of these variables to endurance performance, is a major requirement for coaches and athletes (Bentley, Mcnaughton, Thompson, & Batterhan, 2001).

Heller, et al. (1998) pointed out that Taekwondo could not only improve human cardio respiratory endurance but also enhance practitioners’ martial arts spirit, and form good exercise and self-defense exercise. It also is classified as a high-strength anaerobic capacity exercise. Shin (1993) reported that excellent international Taekwondo athletes must have high speed and power for them to win the international games. The energy system of anaerobic power and anaerobic capacity mainly comes from ATP and Glycolsis system. Taekwondo practice had positive impact on the improvement of human cardio respiratory and physical ability (Pieter et al., 1990).

Heller et al (1998) found that the maximum oxygen consumption volume was 57.0 ml/kg/min in Spanish international Taekwondo athletes and 53.8 ml/kg/min in Czech international athletes. The maximum oxygen uptake in Taekwondo black-belt athletes is 44.0 ml/kg/min (Drobni et al., 1995). Bompa (1999) investigated boxing and martial arts, a quick and powerful start of an offensive skill prevents an opponent from using an effective action. The elastic, reactive component of muscle is of vital important for delivering quick action and powerful starts.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the change of heart rate, oxygen consumption, blood lactate, and urine urobilinogen in resting phase, and in post exercise recovering phase at 5 min, 30 min and 60 min after a total 10-week period including training and competition phases.

II. Study Methods and Procedures

Selection of the Subjects

Ten male TaekwonDo athletes were recruited as volunteer subjects in this study. The mean age, body height, weight, rank, and training experience of these subjects were 19.3±0.5 years, 174.6±2.8 cm, 63.6±1.4 kg, 2.5±0.5, and 6.4±1.0 years, respectively.

Time and Venue

The whole study was completed in the Sports Physiology Lab of Chinese Culture

University, Taiwan. The research of training phase was done from May 11 to 12, 2002. The research of peak phase was done from May 25 to 26, 2002.

Study Methods and Procedures

According to the training content completely controlled by the coach, the training duration is 10 weeks, once every morning for 1.5 hours and every afternoon for 2 hours. The research method was to arrange the subjects to pedal on a bicycle to exhaustion at cycling rate 60 RPM and initial workload 120 W with 30 W increase every 2 minutes. The post-exercise physical changes (heart rate, oxygen consumption, blood lactate, and urine urobilinogen value) were measured in baseline phase, training phase and competition phase, collecting 3 samples in each phase.

(1) Informed consent forms were obtained after the study procedures and potential effects were explained to the subjects, and were understood by the subjects. The status of subjects’ general health was also recorded.

(2) Subjects who were in a bad mood and not in good physical condition were not allowed to perform the test, and were scheduled to return at another time.

(3) 30 minutes before the experiment, the experimental equipment started to warm up, and experimental material was prepared. The subjects were arranged on a bicycle to start pedaling to exhaustion at cycling rate 60 RPM and initial workload 120 W with 30 W increase every 2 minutes. The physical changes (heart rate, oxygen uptake, blood lactate, urine urobilinogen value)were measured at 1. Resting phase 2. First minute of post exercise recovering phase 3. 5th minute of post exercise recovering phase 4. 30th minute of post exercise recovering phase 5. 60th minute of post exercise recovering phase.

(4) During the experiment, the research staff recorded the information obtained from the instruments. When the first experiment ended, the subject would be informed of the time of next experiment.

(5) Study Equipment and Instruments: The following items were utilized in this research:

- SENSOR MEDICS Vmax29 Gas Meter

- YSI2300 PLUS Lactate Analyzer

- DAIICHI 701 Analyzer

- 586 PIII computer and Laser printer

- (POLAR) Mobile heart rate recorder

- Stopwatch

- Hygrometer

Data Management

(1) All data collected from the study were analyzed using 3 statistical software programs: Microsoft Excel 8.0, SPSS/PC 10.0, and SPSS for Windows.

(2) Multiple variants were analyzed by ONE-WAY ANOVA and subsequent Scheffe’ way for post-hoc analysis.

(3) Significant difference was set at α=. 05.

III. Results and Discussion

1.Assessment of Cardio respiratory function

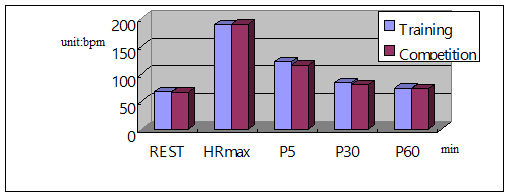

(1)The result of heart rate measurements. There were no statistically significant differences for heart rate between training and competition period(188.7±2.8 vs. 189..6±1.6 bpm , p>.05) (Table 3-1)(Figure3-1). The results showed no overstraining of the heart rate between training and competition period. Arja & Uustitalo(2001) reported overstraining syndrome as a serious problem marked by decreased performance, increased fatigue, persistent muscle soreness, mood disturbances, and feeling ‘burn out ‘ or stale.

Lin & Kuo (2000) found Tae-kwon-Do competition with 3 runs (3 min per run), and 1-min break in every game, the score decides who is the winner. During a game, their heart rates would increase to 165 time/min. Some may reach 192 time/min. It shows that Tae-kwon-Do is a high-intensity exercise, which has greater impact on circulation and respiratory systems. Related to this study, the athletes in different grades of technique and body weight have different fitness physical conditions. Guidetti, Musulin, & Baldari (2002) reported eight elite amateur boxers’ HRmax at 195±7 bpm. The measurement of maximum heart rate is important because it is often used to determine the intensity of cardiovascular training zone. In reality, a larger size athlete would tend to have a lower HRmax value than the predicted value (McArdle et al., 2001). Melhim (2001) et al. found that Tae-kwon-Do exercise could improve children’s cardio respiratory function, improve practitioners’ attack and defense skills and enhance self-health adjusting ability. The result shows that the resting heart rate did not have significant difference after aerobic power training; Anaerobic power and anaerobic capacity had a significant difference, 28% and 61.5% increase respectively; Before and after the training, there was no significant difference in resting heart rate (80.0±6.0 vs. 77.0±9.0 time/min, p>. 05) and in maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max ) (36.3±9.2 vs. 38.2±7.8 ml/kg/min, p>.05). In 80-second Tae-kwon-Do competition, VO2max is 68/ml/kg/min. There was no difference at the heart rate in the training period between post-exercise 60 minute and rest (73.6±3.7 vs. 67.6±3.2 bpm , p>.05). There was no difference at the heart rate in the competition period between post-exercise 60 minute and rest (72.9±3.7 vs. 67.0±2 .0 bpm , p>.05).

Table 3-1 Heart rate comparisons between training and competition n=10 (unit: bpm)

| Rest | Hrmax | post-5 | p-30 | p-60 | |

| Training | 67.6±3.2 | 188.7±2.8 | 121.3±7.0 | 84.2±3.2 | 73.6±3.7 |

| Competition | 67.0±2.0 | 189.6±1.6 | 115.7±13.2 | 80.4±5.8 | 72.9±3.7 |

* means significant different between training and competition

The elite athlete can recover quickly to a rest state and have low a heart rate. Heart rates of general athletes at rest, before and after exercise, were 71, 59, 36 time/min, and their maximum heart rates were 185, 183, 174 time/min, respectively(Jack & David, 1999). The results showed the athletes didn’t recover to the rest period for sixty minutes in the post-exercise between training and competition period. Maybe the players need more time to improve the recovery state. It’s important for the coach and players to improve the recovery system on time because the players have to keep peak performance to success. Prevention is still the best treatment, and certain subjective and objective parameters can be taken by athletes and coaches to prevent over training between practice and competition periods.

Figure 3-1 Heart rate comparisons between training and competition

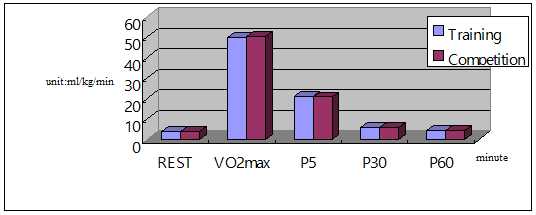

(2)The result of VO2max There was no difference at the VO2max between training and competition period (49.6±3.3 vs. 50.3±3.0 ml/kg/min, p>.05)(Table3-2)(Figure3-2). Drobnic(1995)discussed recreational Tae-kwon-do athletes had a mean VO2max about 44.0 ml/kg/min; however, the VO2max values for elite athletes would be significantly higher than the athletes of recreational level. The National Taekwando Team of China had an average of VO2max of 57.57 ml/kg/min. The mean VO2max value of the Korean National Team, the perennial dominant power of this event, was about 59.56 ml/kg/min (Hong, 1997).Heller et al(1998) reported the average VO2max of the black-belt athletes on the Spanish national squad was 57.0 ml/kg/min, and as for the Czech Republic Team, the value was 53.8 ml/kg/min. Based on the results of previous research, it was suggested that male and female contestants with VO2max of 65 ml/kg/min and 55 ml/kg/min respectively, had a better chance to win Olympic medals. Intensive aerobic training could improve the physiological functions of highly trained sport contestants (Cooke et al., 1997).

Macdougall, Wenger & Green(1990)found ranges of VO2max reported for international athletes in male wrestling, soccer, basketball, and untrained. Their result were 50-70 ml/kg/min, 50-70 ml/kg/min, 40-60 ml/kg/min, 38-52 ml/kg/min. Guidetti, Musulin, & Baldari (2002) examined the physiological characteristics of the middleweight class boxers. Their VO2max at the individual anaerobic threshold was about 46.0±4.2ml/kg/min and their VO2max was 57.5±4.7 ml/kg/min. In addition, their hand-grip strengths and wrist girths were measured and compared to other combat-sports athletes.

In a competitive Olympic (non-professional) boxing match, boxers must fight for a total of 11 minutes. The fight is structured for three 3-minute rounds with a 1-min rest interval between each round. An athlete must have a high anaerobic threshold level and aerobic power level to meet the demand of this sport (Guidetti et al., 2002). Zabukovec & Tiidus(1995) investigated the physiological characteristics of kickboxers .Professional male middleweight (73-77 kg) and welterweight (63-67 kg) kickboxers were determined to have relatively higher aerobic capacities (VO2max, 54-69 ml/kg/min) than previously reported for many other power or combat athletes.

Table 3-2 Oxygen consumption comparisons between training and competition n=10 (unit: ml/kg/min)

| Rest | VO2max | post-5 | p-30 | p-60 | |

| Training | 3.9±0.3 | 49.6±3.3 | 20.8±1.1 | 5.9±0.3 | 4.3±0.1 |

| Competition | 3.8±0.4 | 50.3±3.0 | 20.7±0.9 | 5.9±0.3 | 4.2±0.1 |

*means significant different between training and competition

The results showed lower VO2max than elite players. Therefore, to monitor the phenomena of physiological characteristics to improve the efficiency in the sport science, there was no difference at the VO2max in the training period between post-exercise 60 minute and rest (4.3±0.1 vs. 3.9±0.3 bpm, p>.05). There was no difference at the VO2max in the competition period between post-exercise 60 minute and rest (4.2±0.1 vs. 3.8±0.4 ml/kg/min, p>.05). The result showed similarly between post-exercise 60 minute and rest in the training and competition period , but need more time to recovery in the rest period.

Figure 3-2 Oxygen consumption comparisons between training and competition

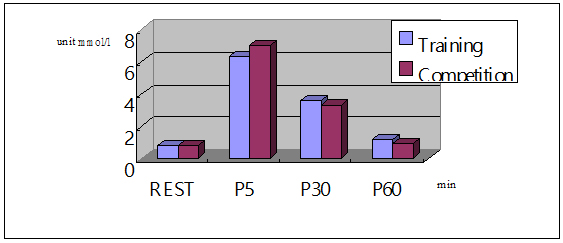

2. The result of blood lactic acid measurement. There was difference at the BLA on the competition period higher than training period (7.0±1.3 vs. 6.3±1.2 mmol/l, p<.05)(Table 3-3)(Figure 3-3). Heller et al (1998) reported that in male and female international TKD competitions, peak blood lactate after 143 seconds could reach the highest, 11.4 mmol/l. The change in the blood lactate has a close relationship with the TKD competition intensity and competition performance (Hultman & Sahlin, 1980). The result showed lowered blood lactic acid than others to improve the intensive training to the player between training and competition period. Hetzler et al (1989) pointed out that excellent martial players should have the characteristics of very good physical ability, high speed and great strength, blood lactate ranging from 1.51-3.23 mol/100 ml, and blood pH value decreasing from 7.39 to 7.34 mg/dl. TKD players not only must have anaerobic metabolism with greater explosive power, but also have very good aerobic endurance; therefore, TKD athletes must have very good anaerobic ability and demand for higher aerobic metabolism capacity (Ho, 1997).

Table 3-3 Blood lactic Acid comparisons between training and competition n=10 (unit: mmol/l)

| Rest | post-5 | p-30 | p-60 | |

| Training | 0.8±0.0 | 6.3±1.2 | 3.6±1.1 | 1.2±0.2 |

| Competition | 0.8±0.0 | 7.0±1.3 * | 3.3±0.7 | 0.9±0.1 |

* means significant different between training and competition

Jack & David (1999) found that the resting blood lactate are 1.0 mmo/l、1.0 mmol/l、1.0mmol/l respectively for ordinary athletes, and international athletes before and after exercise; maximum blood lactate are 7.5、8.5、9.0 mmo/l respectively.

Ho., Chiang & Tsai(1998) found that in 1998 Asia Games, having 4 TKD athletes participate in the winning competition in the training team, the results showed that their maximum blood lactate was 6.74 mmol/l, and BUN tended to increase gradually after competition. From these results, we know although the time of TKD games is short, it may cause the damage in muscle fiber. To excellent athletes, if the quality and quantity of training intensity, cardio respiratory function, energy consumption, and blood lactate system during training can be well controlled, furthermore to well control their body weight and physical ability, the athletes can elaborate their potential and maintain peak performance. It is very important to coaches and athletes (Hiroyuki et al., 1999).

Figure 3-3. Blood lactic Acid comparisons between training and competition

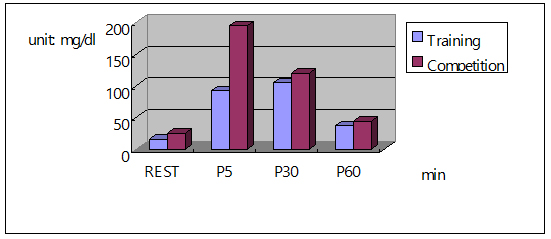

3. The result of URO There was no difference at the URO between training and competition period (92.0±91.1 vs. 195.0±158.4 mg/dl ,p>.05).(Table3-4)(Figure3-4). Urine biochemistry tests can be the evaluation index of nutrition assessment and test exercise intensity (Robert & David, 1993). There was no difference at the URO in the training period between post-exercise 60 minute and rest (36.5±37.2 vs. 15.8±10.4 mg/dl, p>.05).There was no difference at the URO in the training period between post-exercise 60 minute and rest (43.5±35.5 vs. 25.0±12.6 mg/dl , p>.05). The greater the fatigue, the greater the negative training aftereffects such as low rate of recovery, decreased coordination, and diminished power output (Bampa,1999). Related to this study, probably 10-week peak phase of training over-exhausts the physical function and elevates urine protein level that will take longer to recover. Lin(1996)discussed that the factors affecting exercise urine protein included: 1.urine protein and physical function.2.quantity and intensity of training.3.age and environments.4.the effect of emotion on urine protein.

Table 3-4 URO comparisons between training and competition n=10(unit:mg/dl)

| Rest | post-5 | p-30 | p-60\ | |

| Training | 15.8±10.4 | 92.0±91.1 | 105.0±126.1 | 36.5±37.2 |

| Competition | 25.0±12.6 | 195.0±158.4 | 120.0±73.3 | 43.5±35.5 |

* means significant different between training and competition

This finding can be an objective reference factor for contestants in the training and competition. It is possible that nine weeks of training may increase the urine protein level. Urine protein and exercise intensity have strong relationship. Competitive games and high intensity training make urine protein increase. The stronger the exercise intensity, the more the urine protein.

Figure 3-3 URO comparisons between training and competition

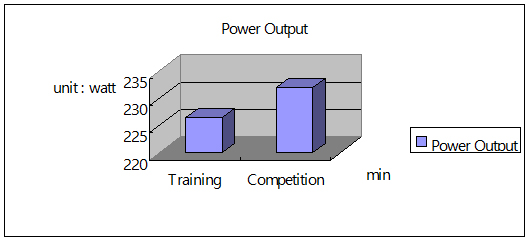

4.The difference of PO(power output) There was difference at the power out at competition period greater than training period (232.7±14.5 vs. 226.5±14.7 watt ,p<.05) (Table3-4) (Figure3-4). It could be training for 10th week to promotion the muscle of power output. Zabukovec & Tiidus (1995) investigated professional male middleweight (73-77 kg) and welterweight (63-67 kg) kickboxers. The results showed relatively anaerobic capacities (8.2-11.2 Watt/Kg) than previously reported for many other power or combat athletes. The results showed lower than Kickboxers’ anaerobic capacities. Hoffman & Kang (2002) investigated a major concern of many of these studies focused on the applicability of a cycle ergo meter test for anaerobic power in athletes that perform primarily sprinting activities. To find the peak power of the football, basketball, wrestlers, male physical education students were 16.8±5.2 w/kg, 21.8±5.0, 18.5±2.7, 18.8±5.6 W/kg. Female group of the soccer and physical education students in peak power is 15.7±4.2 and 12.9±3.0 W/kg. However, the results showed lowered power output than others to improve the athlete’s muscle power to promote the physical state.

Bompa (1999) investigated strength training has become widely accepted as a determinant element in athletic performance. Thus, the main objective of the conversion phase is to synthesize those physiological foundations for advancements in athletic performance during the competitive phase. The determining factors in success of the conversion phase are its duration and the specific methods used to transform M*S gain into sport-specific strength.The power value measured by the simple product of the applied force and the speed developed remains inferior to the real power performed by the subjects since the forces of friction and inertia are not taken into account (Arsac et al.,1996).Thus other factors, such as metabolic and structural properties of taekwon-do players’ muscles, should be considered.

Therefore, martial arts and boxers must be able to react quickly and powerfully to an opponent’s attack. Both aerobic and anaerobic energy is used during a bout. Reactive strength and agility are necessary to respond to an opponent’s strategy. Limiting factors: Power endurance P-E), reactive power, M-E (muscle endurance)medium or long(professional boxer (Bompa,1999).

Taekwon-do exercises the need for stronger power including speed and velocity. Power is the ability of the neuromuscular system to produce the greatest possible force in the shortest amount of time. Power is simply the product of muscle force (F) multiplied by the velocity (v) of movement: P=F*V for athletic purpose, any increase in power must be the result of improvements in either strength, speed, or a combination of the two (Bompa, 1999).

Table 3-4 Power Output comparisons between training and competition n=10 (unit: watt) ; average power: AP

| Power Output | |

| Training | 226.5±14.7 * |

| Competition | 232.7±14.5 |

*means significant different between training and competition

The advantage of explosive, high-velocity power training is that it “trains” the nervous system. Increase in performance can be based on neural changes the help the individual muscles achieve greater performance capability (Scale,1986). This is accomplished by shorting the time of motor unit recruitment, especially FT fibers, and increasing the tolerance of the motor neurons to increased innervations frequencies (Hakkinen, 1986; Hakkinen & Komi,1983). The other way, it’s important technology for the coach and player to improve the starting power because it is an essential and often determinant ability in sports where the initial speed of action dictates the final outcome (boxing, karate, fencing, the start in sprinting, or the beginning of an aggressive acceleration from standing in team sports). The athlete’s ability to recruit the highest possible number of FT fibers to start the motion explosively is the fundamental physiological characteristic necessary for successful performance (Bompa,1999).

Figure 3-4 Power Output comparisons between training and competition

IV. Conclusion

- There was no difference of the cardiac respiratory functioning between training and competition period. The players can’t recovery quickly for sixty minutes.

- There was a difference at the BLA at the competition period higher than training period. To improve the intensive training to the player between training and competition period.

- There was no difference at the URO between the training and competition period in the post-exercise 60 minute and rest.

The competition period was greater than training at the power out, but less than elite athletes in the professional period. Athletes are constantly exposed to various types of training loads, some of which exceed their tolerance threshold. When athletes drive themselves beyond their physiological limits, they risk fatigue (Bompa,1999). Thus, to monitor the physiological characteristics between training and competition period. It’s benefit for the player and coach to manage the peak performance and avoid the over training. To recover quickly and keep a steady state is important for the coach and player.

Reference

- Arja, L.T.,& Uusitalo(2001).Overtraining-Making a Difficult Diagnosis

and Implementing Targeted Treatment. The Physician and Sportmedicine,29(5),1-14. - Bentley, D.J., Mcnaughton, L.R., Thompson, D.,& Batterham, A.M.(2001).

Peak power, the lactate threshold, and time trail performance in cyclists.

Medicine Science Sport Exercise. 33(12),2077-2081. - Bompa, T.O.(1999). Periodization training for sport. Champaign,

IL: Human Kinetics. - Cooke, S.R., Patersen, S.R.,& Quinney ,H.A.(1997). The influence

of maximal aerobic power on recovery of skeletal muscle following aerobic

exercise. European Journal of Physiology, 75, 512-519. - Drobnic, F., Nunez, M., Riera, J. et al.(1995). Profil de condition

fisica del equipo national de Taekwon-Do. In 8th FIMS European Sports

Medicine Congress. Granada, Spain. - Guidetti, L., Musulin, A.,& Baldari, C.(2002). Physiological factors

in middleweight boxing performance. Journal Sport Medicine Physical

Fitness, 42, 309-314. - Hakkinen, K.(1986).Training and detraining adaptations in electromyography.

Muscle fiber and force production characteristics of human leg extensor

muscle with special reference to prolonged heavy resistance and explosive-type

strength training. Studies in Sport, Physical Education and Health.

20. - Hakkinen, K.,& Komi, P.(1983).Electromyographic changes during strength

training and detraining. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise.15,455-460. - Heller, J., Peric, T., Dlouha, R. et al.(1998). Physiological profiles

of male and female taekwon-do (ITF) black belts. Sports Science. 16:243-9. - Hetzler, R. K., Knowlton, R. G., Brown D. D. et al.(1989). The effect

of voluntary ventilation on acid-base responses to a Moo Duk Tkow form.

Research Quality for Exercise and Sports. 60:77-80. - Hiroyuki Imamura, Yoshitaka Yoshimura, Seiji Nishimura et al.(1999).Oxygen

uptake, heart rate, and blood lactate response during and following karate

training. Medicine and Science in Sport and Exercise. 31(2):342-346. - Ho, C.F., Chiang, J.S.,& Tsai, M.J.(1998), The impact of Taekwon-Do

on urine lactate, blood urine nitrogen and serum creatine kinase. The

essay collection of 1998 International Junior College Coach Conference. - Hong, S.L.(1997a), Research in physiologic biochemistry characteristics

of Korean excellent TKD athletes. Beijing: Sports University College

News, 20 (1), 22-27. - Hong, S. L. (1997b). Physiological and biochemical characteristics of

excellent Korean contestants of Taekwondo. The Academic Journal of

Beijing Physical Education University, 20(1), 22-29. - Hultman, E.,& Sahlin, K.(1980). Acid-base balance during exercise.

Exercise and Medicine in Sport Science Reviews. 8,41-128. - Jack, H.,W.,& David, L.C.(1999). Physiology of Sport and Exercise.

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. - Lin, G.Y.,& Kuo, Y.A.(2000), Maximum oxygen uptake, blood lactate

and serum LDH activity of Taekwon-Do athletes before and after competition.

China Sports Technology, 36 (1). - Lin, W.(1996). Biochemistry assessment of Sports Burden. Guang-Dong

Higher Education Publisher. - McArdle, W.D., Katch, F.I.,& Katch, V.L.(2001). Exercise physiology:

Energy, nutrition, and human performance (Fifth Edition). Baltimore,

Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. - Melhim, A.F.(2001). Aerobic and anaerobic power responses to the practice

of taekwon-do. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 35(4):231-234. - Pieter, W., Taaffe, D.,& Heijmans, J.(1990). Heart rate response

to Taekwon-Do forms and technique combinations. Journal of Sports Medicine

and Physical Fitness. 30:97-102. - Sale, D.(1986). Neural adaptation in strength and power training. Human

Muscle Power. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. - Shin, J.K.(1993). Train to be a champion. World Taekwon-Do Federation

Magazine.47,63-66. - Zabukovec, R.,& Tiidus, P.M.(1995). Physiological and anthropometrical

profile of elite kick boxers. Journal of strength and conditioning

research. 9(4).240-242.