Physical Activities and Their Relation to Physical Education: A 200-Year Perspective and Future Challenges

Submitted by Suzanne Lundvall and Peter Schantz.

The Sport Journal normally doesn’t publish articles that have appeared in other publications previously, but the entry below is an exception to this rule. We at The Sport Journal feel the views expressed in this article are important enough to republish for our valued readers.

Abstract

In this macrolevel overview, a model of the multiplicity of the field of bodily movement cultures is initially presented. The model is then used to illuminate how different bodily movement practices emerged over time, became embedded, remained, faded, or disappeared in the world’s oldest physical education teacher education (PETE) program. Through this continuity and discontinuity of practices, five distinct phases are identified, although sometimes intertwined, and their contextual background is described. The first phase is characterized by the establishment of Ling gymnastics from the early 19th century and by its fall in the 20th century. The next phase started in the late 19th century and dealt with the introduction of sports and outdoor life. During a third phase, sports became the dominating movement practice. The fourth phase is related to the rise and fall of a separate female gymnastics culture during the 20th century. The fifth phase is characterized by the introduction of everyday life physical activities at the beginning of the new millennium. The overview is followed by reflections on the future content of bodily movement practices and sought-after values in PETE and physical education in the school system.

Introduction

The content of physical education (PE) programs in schools for children and young people is under debate globally. This is not new. PE has had an ongoing battle concerning how to gain the greatest and longest benefits for mind and body since it was established at the beginning of the 19th century (Pfister, 2003). These conflicts have been noted between cultures and nations, representing different points of view about the legitimate agenda of physical education, but conflicts have also been noted within nations and educational institutions (Kirk, 2010; Korsgaard, 1989; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003; Morgan, 2006; Pfister, 2003; Schantz, 2009; Schantz & Nilsson, 1990). In the authors’ view, good reasons exist to continue this debate in our time. For this purpose, a model of the multiplicity of the field of physical activity cultures is presented. It is offered as a supportive and clarifying structure for identifying, discussing, and making future PE content decisions.

To illuminate these issues, the model is used in a macrolevel overview, illustrating changes in values and practices within the oldest still existing physical education teacher education (PETE) program in the world, that is, The Royal Gymnastic Central Institute (GCI), now named The Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences (GIH). Apart from studies based on empirical data from this PETE institution, the overview also makes use of international literature on physical culture and health.

Thus, this article focuses on PETE, a less examined area when it comes to how new concepts of bodily movement practices have emerged, become embedded in programs and local

practices, remained, faded, or disappeared because they were not “legitimate” or were of less value or for other reasons (e.g., Annerstedt, 1991; Fernandez, 2009; Kirk & Macdonald, 2001; Kirk, Macdonald, & Tinning, 1997; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003). Proceeding from these basic concepts, the final aim of this article is to reflect and discuss the present-day situation in relation to principles for bodily movement practices and sought-after values for PETE. This discussion will include tensions and disagreements on content issues and future challenges for PETE and school PE.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical departure point is inspired by the work of Bourdieu. The analytical focus has been placed on how deliberate forms of bodily movement practices in the studied PETE program came to be defined and regulated through meaning-making principles or the logic of practices (Bourdieu, 1984, 1990; Engström, 2008). Over time, the chosen bodily movement practices have created tensions in terms of power and control over what has been seen as legitimate in the educational sector of physical activity and body culture. This departure point also makes it possible to study how aspects of investment and intrinsic values have been put forward and have been related to views on body and health.

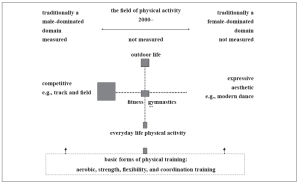

The Educational Field of Physical Activity Practices: A Model

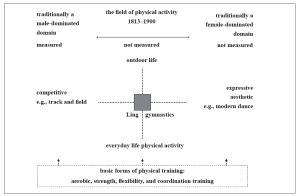

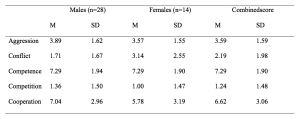

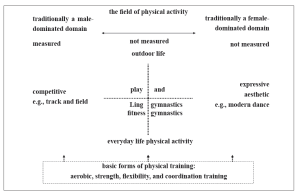

A model has been developed to illustrate the multiplicity of different forms of deliberate bodily movement practices with distinctly different meaning-making principles (logic of practices; Figure 1). It also considers the construction of gender. It is based on a similar model first described by Schantz and Nilsson (1990) and relates to an educational context in Sweden. However, it can also be easily adjusted to conditions in other countries. The different principles for bodily movement practices are spatially oriented in the model in relation to the rationality underpinning each practice. Sport activities, based on the logic of competition, are placed in the traditionally male-dominated domain. Aesthetic and expressive forms of physical activities, such as artistic forms of dance, are placed in the traditionally female-dominated domain. Ling gymnastics, fitness gymnastics, play, outdoor life, and everyday life physical activities are placed in a traditionally gender-neutral position in the middle of the model. None of these forms of movement practices are underpinned by measurement/competition or driven by aesthetics and expressiveness. Enhancement of different physical qualities through physical training can support the conduct of all movement practices in the model. Basic forms of physical training are therefore placed at the bottom of the model, with arrows signaling their possible supportive nature for all other movement practices. Physical activities that are related to different types of professions are not given a place in this model.

Figure 1. A Model of the Field of Physical Activity Practices (modified from Schantz &

Nilsson, 1990)

Continuity and Discontinuity of Bodily Movement Practices Over Time

A general description is given below of how the model can be used to illuminate the relative amount of time devoted to different movement practices during different time periods. In this way, a flow of continuity and discontinuity emerges. Different distinct phases are noted. This primarily visual description is followed by a text elaborating contextual factors of importance for understanding the changes described.

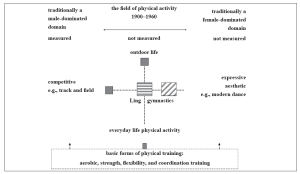

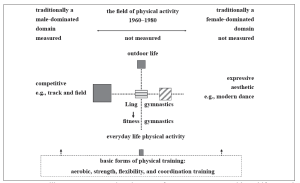

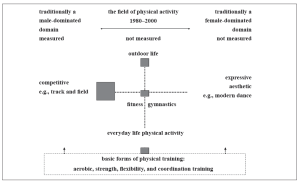

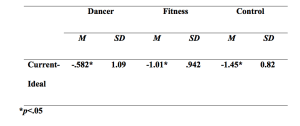

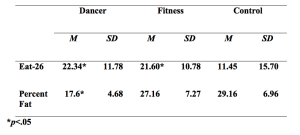

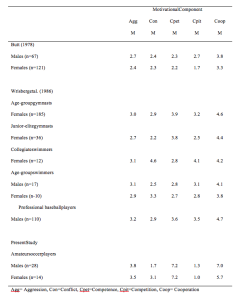

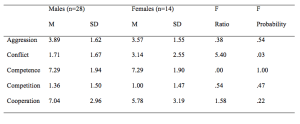

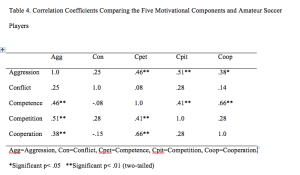

From 1813 to 1900, Ling gymnastics was developed and dominated the movement practices, and a fundamental principle was the schooling of body and character (Figure 2). From 1900 to 1960, sports were gradually introduced and thereby the logic of competition. PETE also started to involve outdoor life with the main goal of experiencing nature. For this purpose, physical activities such as orienteering and skiing became part of the educational program. Female PETE education developed a gymnastics discourse of its own, with influences from dance, rhythmic, and aesthetics. Thus, different and gender-related dimensions of movement practices became represented. Alongside this, new forms of physical training, particularly circuit training and aerobic conditioning, were brought in and signaled a logic of training solely for an investment value (Figure 3). During the period from 1960 to 1980, the elements of Ling gymnastics generally faded away but left a space for fitness gymnastics, and at the beginning, this was divided for men and women. Sport dominated as a movement practice, and fitness training within the area of gymnastics increased. The position for outdoor life activities remained stable (Figure 4). From 1980 to 2000 the separate female gymnastic discourse ended as an unintended consequence of a coeducational reform. Sport as a movement practice dominated and became the primary rationale for PETE. Fitness gymnastics was available for male and female students.Outdoor life held its position (Figure 5). From 2000 and onward, everyday life physical activity

emerged with its fundamental principle of an investment value in health. In other ways, there was no fundamental change compared to the previous period (Figure 6).

Figure 2. Bodily movement practice in PETE from 1813 to 1900. Ling gymnastics was developed and established. It represented the content in male and female PETE (where female PETE was established in 1864; cf. Drakenberg et al., 1913). This is indicated by the gray field, which signifies teaching time allocation to this specific bodily movement practice.

Figure 3. Bodily movement practices in PETE from 1900 to 1960. Male and female gymnastics, indicated as boxes with horizontal and diagonal lines, respectively, developed in different directions. In the 1950s, new forms of physical training appeared. The sizes of the gray fields represent an approximate relative balance between time allocated to different physical activity practices at the latter part of the time period (cf. Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003; Tolgfors, 1979). The years indicated as the beginning and end of the period should be read as approximate indications of time.

Figure 4. Bodily movement practices in PETE from 1960 to 1980, with a shift toward more time being allocated for sports and a gradual shift away from Ling gymnastics toward fitness gymnastics (cf. Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003; Tolgfors, 1979). For general comments on the construction of the figure, see Figure 3.

Figure 5. Bodily movement practices in PETE from 1980 to 2000 differ from the previous practices (see Figure 4) in that the coeducational reform led to the termination of the separate female gymnastics culture (cf. Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003; Schantz & Nilsson, 1990). For general comments on the construction of the figure, s ee Figure 3.

Figure 6. Bodily movement practices in PETE in the 21st century. A dimension of “everyday life physical activity” was introduced during this period (Idrottshögskolan, 2002, 2003). The other movement practices remained the same compared to the previous phase, with one exception: The time alotted to “basic forms of physical training” was reduced; see Figure 5 (cf. Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003, 2012). For general comments on the construction of the figure, see Figure 3.

Contexts of Emergence, Continuity, and Discontinuity of Bodily Movement Practices

Emergence of PETE in Sweden

The early 19th century was a time open for new concepts about the training of the body. This process, which was connected to the Enlightenment and the growing importance of rational and acting, as well as the faith in scientific thinking, made it possible for new concepts and ideals to develop, including a specific exercise culture of physical education (Pfister, 2003). The institutional setting for Swedish gymnastics came about when Per Henrik Ling was given permission to establish the Royal Gymnastic Central Institute (GCI, today GIH) in 1813. This was also the starting point for the emergence of PETE in Sweden. Ling wanted to provide a system on a theoretical basis and resting on philanthropical ideas, “the philosophy of nature,” inspired by Rousseau and GutsMuths, where the intellect could be developed through the senses and action. The other basis for his system was that it was intended to rest on the “laws of the human organism” and on knowledge gained from studies of the human body. His thinking resulted in certain ideas about the execution of movements and schooling of the body, which were tightly linked to Lings’ ethical and aesthetic ideals and to perspectives of health regarded as a wholeness.

Ling aimed to develop a gymnastics system with four subdisciplines: pedagogical, medical, military, and aesthetic gymnastics. Hence, Swedish gymnastics came to be seen not only as a system for the purpose of educating the whole body, but also as a cure for the sick. Aesthetic gymnastics “whereby one expresses the inner self: thoughts and emotions” (Ling, 1840/1979, p.50) was subjected to only minor developmental attempts.

This article focuses on pedagogical gymnastics, which was defined as the means “whereby one learns to master one’s own body” (Ling, 1840/1979, p. 52). To correctly cultivate the human body, according to Ling (1840/1979, p. 54), required an elaborate system of different to promote the ability for movement control and competence. These movements were determined in detail with regard to starting and final positions, as well as the trajectory and rhythm of such movements. The system included a well-reasoned progression from easy to more complicated movements. The movements could be executed as freestanding exercises, without support, or as exercises supported by gymnastics apparatus, but all movements are based on the above-mentioned central aspects. This form of pedagogical gymnastics also had a statuesque aim (i.e., to develop a harmonious and symmetric body with good posture). Competition was not the aim or the medium of this specific movement practice, and it was not included in the praxeology (Lindroth, 1993/1994, 2004; Ling, 1840/1979; Ljunggren, 2000; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003).

From early on, Ling stated that women should be included in this form of bodily exercise, in a feminine type of gymnastics. However, this type of gymnastics was never developed by Per Henrik Ling himself, but rather was developed later through the work of his son, Hjalmar Ling, who gave examples of simple forms of gymnastics for female students (Lindroth, 2004; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003). Throughout the first 100 years at GCI, the teacher training of male and female students, in both theory and practice, was focused on gymnastics, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Tensions and Conflicts Around Ling Gymnastics

In the early 1900s, the scientific basis of the Ling gymnastic system was strongly questioned. This critique was primarily based on scientific studies of a specific movement that was claimed by the Ling gymnasts to enlarge the vital capacity and thereby improve oxygen uptake (Lindhard, 1926; Schantz, 2009; Söderberg, 1996). At GCI there had been, until the early 20th century, surprisingly small-scale efforts to increase the scientific understanding of Ling gymnastics in terms of their own knowledge production (cf. Lindroth, 2004). From the early 20th century there was, however, a clear ambition in this respect. A proposal to establish professorships in physiology, anatomy, histology, psychology, and pedagogics, as well as three in pedagogical gymnastics, was put forward in 1910. However, in those days the national government and parliament made such decisions, and not until 1938 was a decision made to establish a professorship in the physiology of bodily movements and hygiene (Schantz, 2009). In spite of this tension created by the accusation of a nonscientific bodily movement practice, Ling gymnastics kept its position as the main body exercise system into about the middle of the 20th century in combined 9-year elementary and junior high schools in Sweden (Lundquist Wanneberg, 2004) as well as in other countries (Kirk, 2010). One explanation for this long survival was its strong institutionalization, represented by the GCI, and its existing views on body, health, and physical culture, which constituted a strong health and hygiene discourse aimed at defeating, for example, infectious diseases and crooked bodily postures, and at strengthening character through education (Bonde, 2006; Palmblad & Eriksson, 1995). This health and hygiene discourse and the tight relationship between pedagogic and physiotherapeutic gymnastics gave legitimacy to Swedish gymnastics. Furthermore, this type of bodily exercise also encompassed PE for girls, which, over the years, led to a strong female PETE culture. From a societal perspective, this suited the task of PE well. The alternatives for bodily exercise and the training of girls’ bodies were few in number at that time (Carli, 2004; Kirk, 2010; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003). Furthermore, from the point of view of scientific legitimacy, there were no alternatives to Ling gymnastics. Thus, sports, for example, could not compete with Ling gymnastics in this respect.

From Gymnastics to Sports: The Process of Sportification of PETE

During the first half of the 20th century, sport with its logic of competition was introduced as part of the bodily movement culture at GCI and expanded gradually to become an equal part of the PETE training practice as compared to Ling gymnastics. When Ling gymnastics rapidly lost its dominating position from the 1950s to 1960s, sports overtook that role (cf. Figures 3 and 4). From the mid-1960s, the study hours for courses in sport disciplines started to outnumber those for gymnastics (Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003). To understand these changes in physical practices in PETE, it is important to understand how sport as a physical culture spread during the 19th and 20th centuries in Sweden and globally. A vast amount of literature has described how the rise of organized sports took off in such an emphatic way. Undoubtedly, there is, as Pfister (2003) notes, “a connection between the rise of sport and the adoption of values, standards and structures of industrialization—including rationality, technological progress, the abstract organization of time and an economy aimed at accumulation of capital” (p. 71). Linked to these societal processes was also the reformation of the public school systems, which required a system for the changing ideals of manliness, where the idealization of fair play, together with an appreciation of individual achievement, competitive in character, represented values to be sought after (Mangan, 1981a, 1981b). The average man was considered superior to the average woman, with women being seen as weaker and lacking potential (Pfister, 2003; Wright, 1996). Darwinism also played an important role in forming the sports ideology: the application of Darwin’s theory of natural selection as an argument for maintaining a strong defense for the survival of the fittest, which was to be achieved by means of persistent athletic exercises and competitions (Sandblad, 1985).

In Sweden, the breakthrough for the establishment of the sports movement occurred when the first sports organization became government financed (1913) and a part of the nation’s social and moral program (cf. Lindroth, 2004). As support grew during the first decades of the 20th century, sport was taken on by PETE as well as in PE in schools. The fundamental principle of Ling gymnastics thereby became less exclusive, appeared to be of less value, and was less sought after. The representatives of Ling gymnastics were surprised that sport, which had earlier been for the upper classes, was suddenly available to the wider masses (Lindroth, 2004).

The spread of sport after World War II was also accompanied by influences of a type of physical training—circuit training—originally emerging from military training. These influences brought in new principles concerning how the training of the body was to be planned and executed (Morgan & Adamson, 1961). Effective training during short periods of time, possible to be executed in small spaces, was in many ways revolutionary compared to the more complicated exercise programs in gymnastics. The emergence of exercise science (cf. Åstrand & Rodahl, 1970), not the least with regard to aerobic conditioning, gave sport and fitness training further legitimacy at GCI (Schantz, 2009). At first, the principles of training represented by circuit training were implemented as part of male gymnastic training (Figure 3).

Alongside the sportification process, the female branch of Ling gymnastics challenged its traditional practice from the beginning of the 20th century and was influenced by an elaborated theory of body and rhythm and the concept of effort saving (Laine, 1989). Initially, these influences, involving breaking with the stiff traditional floor-standing gymnastics, met opposition and resistance (Forsman & Moberg, 1990; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003). But it was not possible to stop this development and changing of “logic” to aesthetics because it could be justified as being in line with Ling’s intentions concerning the aesthetic branch of his system (see Figure 3). Another process that demonstrated elasticity in the application of the principles of Ling was the development of PE and children’s gymnastics toward a more natural and child centered way of moving, away from drill and command (Falk, 1903, 1913).

The nature of female gymnastics embodied values of emotions and how to put one’s soul into the movements, to liberate the body, and to provide space for self-education (Carli, 2004; Laine, 1989; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003). The performing of movements was characterized by sensitiveness, adaptability, body awareness, and expression—the feeling of the movement. This type of body training, based on what today is called a subjective experiencing of the body (body-as-subject), provided cultural, physical, and symbolic capital that did not challenge the existing ideals of the female body at that time. Both of the above-mentioned processes must be acknowledged as mechanisms for understanding the long survival of Swedish gymnastics in the PETE programs and in school PE. The corresponding development of the male Ling gymnastics was not the case (Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003).

The popularity and success of the spread of sports is both easy and not easy to understand. With regard to former principles for the education of body and mind, it is interesting how sport, with its meaning-making principles of competition and specialization of skills, with the training of the body as an objective, could fit in so easily and replace the old virtues of the training of the body, regarding health as wholeness, without the dualism of body and soul.

The introduction of outdoor life in PETE from 1900 to 1960 (Figure 3) can be understood in relation to the organization phase of outdoor life in the late 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. It reflects a need for new identities due to both the great demographic changes with the strong urbanization processes during this period and also the concomitant nationalism and strong surge for new national identities. In this identification process, love of nature as well as skiing emerged as strong parts of the identity profile for Swedes (cf. Sandell & Sörlin, 2008).

From Two-Gender Specific PETE Cultures to One: A Merging With Consequences

During the 1970s political striving for equal rights and employment in Sweden led to questioning of the organization of gender-separated PETE programs. Suddenly old ideals stood beside new ones. The process of integration of the male and female PETE cultures as well as the sportification process of bodily movement practices led not only to a new gender order and a loss of the female gymnastics culture, but also to a marginalization of the female PE pedagogical culture (Carli, 2004; Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003; Schantz & Nilsson, 1990; cf. Figures 4 and 5). For corresponding changes in other countries, see Kirk (2010), Wright (1996), and O’Sullivan, Bush, and Gehring (2002). Furthermore, the time allotted to courses in gymnastics decreased substantially after the coeducation reform in 1977 (Lundvall & Meckbach, 2003). The long tradition of female PETE culture, together with school PE steering documents, prevented a total termination. Courses in dance, music, and movement remained as minor parts of the coeducational PETE study program, but were aimed more at fitness gymnastics, such as workouts and aerobics (Figure 5). Former practices with their fundamental principles of aesthetics became simplified.

At GCI–GIH, the total amount of practical courses went from being the major portion of the study programs during the early 20th century to becoming more peripheral, from taking up 80% of the total study time in the 1920s to less than 15% about 90 years later (Lundvall & Meckbach, 2012; Tolgfors, 1979). A parallel academization process of PETE took place in general, and globally, after the 1970s (e.g., see Kirk, 2010; Kirk et al., 1997; Tinning, 2010).

Everyday Life Physical Activity as Bodily Movement Practice: Disagreements in Modern Time During the late 20th century, new and other practices of physical activity started to be demanded. Recommended amounts and levels of physical activity were distributed in 1996 by the U.S. Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996). This way of thinking about children’s and young peoples’ needs for physical activity bore some resemblance to former medical arguments for the prevention of disease and for the curing of the sick that started nearly 200 years earlier.

Everyday life physical activity as a way of thinking gradually became established in society around the beginning of the 21st century, originally taken on by stakeholders in public health, actors outside the field of PETE, and academic disciplines related to sports (Ainsworth, 2005; McKenzie, Alcaraz, Sallis, & Faucette, 1998; Morgan, 2000). This thinking signaled that children and adolescents need to learn how to become and stay physically active in everyday life (McKenna & Riddoch, 2003; Smith & Biddle, 2008; Trost, 2006). Changes in society had led to a focus on physical inactivity among the population. This scenario developed even though there had never before been so many opportunities for participation in organized sports. An outspoken fear of to what physically inactive lifestyles could lead among young people (including reports of obesity crises) was strongly communicated (World Health Organization, 2002). Once again, the question of how physical exercise could contribute to the health of a nation’s citizens came up on the political agenda.

The sought-after legitimatizing educational values and logic of practices behind this new way of thinking have not been clearly communicated so far. The rationale behind the emphasis on everyday life physical activity has given rise to criticism. Educational sociologists point out that school PE cannot only be driven by a medical risk discourse, or a pathogenic and/or normative way of thinking of physical activity and health (Gard & Wright, 2001, 2006; Kirk, 2010). Physical education is much more: It is about physical self-esteem, body awareness and abilities, personal and social development, questions of democracy, as well as critical aspects of health and health communication (Evans, 2004; Evans, Davies, & Wright, 2004; Macdonald & Hay, 2010; Siedentop, 2009). This can perhaps explain to some extent why PETE educators have shown a cautious attitude toward how the thinking about everyday life physical activity has been exposed and how it has been attempted to be implemented. It is too early to describe with any certainty how and what the construction of knowledge around everyday life physical activity will represent in terms of new or renewed bodily movement practices in the area of PETE in general and globally.

The first compulsory course in everyday life physical activity at GIH was started in 2004 in two transdisciplinary courses (Idrottshögskolan, 2002, 2003), which were demanded in a teacher education reform (Figure 6). These dimensions of human movement were introduced in a context of physical activity, public health, and sustainable development (Schantz, 2002, 2006; Schantz & Lundvall, forthcoming). Hence, it is possible to state that learning sports as the predominant bodily movement practice in PETE programs and school PE has been challenged.

Post-Overview Reflections

In this article, a model clarifying the multiplicity of fundamental principles and dimensions of bodily movement practices in a specific, but for the development of PETE, central setting in Sweden has been presented. The model has been used to illustrate the continuity and discontinuity of movement practices. Thereafter, mechanisms and contextual backgrounds to these changes over time have been described.

Although national and cultural differences in how countries organize their PETE programs and school PE exist, there are reasons to believe that the similarities of the development described outnumber the differences. The scheme of continuity and discontinuity stimulates a discussion about what values have been gained, what has been lost, and what possible values have not been introduced as part of PETE.

The introduction of new physical activity logics in PETE has sometimes been dependent not only on the meaningfulness of a certain logic but also on power relations. The introduction of sport is such an example. Furthermore, there are also examples of dramatic changes that have taken place without being desired or planned for intentionally. The rapid decline of female gymnastics at the beginning of the 1980s as a result of the introduction of coeducation is an example. Furthermore, Ling gymnastics faded away after World War II and, with that, faded the principles of movement practices aimed at dimensions such as general body awareness, posture, and ability to maintain motor control. Again, these consequences were not foreseen.

Another lesson is that such unforeseen consequences can be difficult to handle in terms of compensatory pedagogic actions. The values of the female gymnastics and the Ling gymnastics were dependent on strong framing cultures that had been developed over long periods of time, and indeed, the creation of new cultures fostering the best values of those previous cultures is difficult to achieve. Therefore, as a memento, it is suggested that, before changing the content of PETE, one should try to create different scenarios to counteract the possibility that that decision may lead to unforeseen effects.

The overview also makes it clear that the dimension of movement practices connected to different forms of artistic dance have been left out in PETE. This exclusion has, with few exceptions (Schantz & Nilsson, 1990), not been an issue that has been discussed. Indeed, most likely, this would not have been the case if it had been a traditionally male-dominated domain of physical activity. Among these gender issues is also that females taking up different forms of traditionally male-dominated sports is appraised positively, whereas attempts in the opposite direction are generally few in number or entirely absent and lack clear support in the currently governing mind-sets within PETE.

The existence of a multiplicity of logic of movement practices in the field of physical activity points to distinct values of each of the fundamental principles underlying these practices. In line with this, the interaction between different kinds of movement practices and the individual enlarges his/her points of reference in relation to body, movement, and mind.

With such a view constituting a rationale for different physical activities in PETE, one can ask what balances in time allocation are reasonable for attaining a goal of widening the personal experiences and securing “breadth” as an educative value of its own. This takes into account that most of the PE students of today have a strong personal experience in sports, whereas their experience with other physical activity cultures is meager (Brun Sundblad, Meckbach, Lundvall, & Nilsson, 2010). They have what Bourdieu would call a strongly developed taste for sport, forming part of a strong sport habitus (Bourdieu, 1984; Engström, 2008).

Another dimension of reflection on the PETE content deals with what PE contents in schools may be important for adult behavioral patterns of physical activity. Not much cross-sectional or longitudinal research exists on those issues, but there are indications that socializing into sport activities might not effectively foster physically active lifestyles among adults. Instead, schooling into a broad movement repertoire, as well as experiences of outdoor life, appears to be more effective in this respect (Engström, 2008).

Recent knowledge highlights that, in relation to physical activity, one has to take into account the multiplicity and complexity of young peoples’ lives. Context and social interaction play a central role. Children and adolescents are social actors that navigate in the landscape that surrounds physical movement culture. More attention has to be given to how the “healthy citizen” is constructed. What does it mean to live on the countryside, to live in inner cities, or to have the gym or the sport club as the social place for physical activities? In what ways does the place create meanings and relations? And for whom? Which physical activities are included or excluded (Wright & Macdonald, 2011; Thedin Jakobsson, in press)? According to current reports and research studies on school PE in Sweden, students learn sports but not about health and how to take responsibility for healthy physically active lifestyles (Lundvall & Meckbach, 2008; Quennerstedt, Öhman, & Ericson, 2008; Skolinspektionen, 2010). These issues have also been highlighted globally (Hardman & Green, 2011; Green, 2008; Pühse & Gerber, 2005)

New scenarios concerning health, well-being, and illness, including rising numbers of school students experiencing stress and forms of psychological unhealthiness (Folkhälsoinstitutet, 2011), migration, economic recessions, growing segregation among social classes, and an uneven distribution of access to physical activity and health knowledge, have continued to challenge the stability of health among societies’ citizens. The overview relates the content matter of PETE over time to influences of different societal contexts. From this perspective, the relation of physical activity in PETE to major current societal challenges, such as the obesity and type 2 diabetes epidemics, as well as issues related to sustainable development (cf. Schantz & Lundvall, forthcoming) and globalization, are examples of matters that deserve to be thought through and discussed in much more depth than what appears to be the case in most PETE institutions and countries at present.

References

1. Ainsworth, B. (2005). Movement, mobility and public health. Quest, 57, 12–23.

2. Annerstedt, C. (1991). Idrottslärarna och idrottsämnet [The PE teachers and the subject of PE] (Doctoral dissertation). Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden.

3. Åstrand, P.-O., & Rodahl, K. (1970). Textbook of physiology: Physiological bases of exercise. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

4. Bonde, H. (2006). Gymnastics and politics. Niels Bukh and male esthetics. Copenhagen, Denmark: University of Copenhagen, Museum of Tusculanum.

5. Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of judgement of taste. London, England: Routledge.

6. Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

7. Brun Sundblad, G., Meckbach, J., Lundvall, S., & Nilsson, J. (2010). Orka hela vägen. Upplevd hälsa, idrotts- och träningsbakgrund bland studenter på en fysiskt inriktad yrkesutbildning. Lärarstudenter GIH 2008, delrapport 1: 2009 [Managing all the way. Self-reported health, sports and training background of students in physical activity-related higher education programs. Teacher students, GIH 2008, partial report 1:2009]. Stockholm, Sweden: Gymnastik- och idrottshögskolan.

8. Carli, B. (2004). The making and breaking of the female culture. The history of Swedish physical education ‘in a different voice’ (Doctoral dissertation). Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden.

9. Drakenberg, S., Hjort, C., Nerman, E., Levin, A., & Svalling, E. (1913). Kungliga Gymnastiska Centralinstitutets historia 1813–1913, utgiven av dess lärarkollegium med anledning av institutets 100-års dag [The history of the Royal Gymnastics Central Institute 1813-1913, published by its academic council on the occasion of the Institute’s 100th anniversary]. Stockholm, Sweden: Kungliga Gymnastiska Centralinstitutet.

10. Engström, L.-M. (2008). Who is physically active? Cultural capital and sports participation from adolescence to middle age—A 38-year follow-up study. Sports Pedagogy and Physical Education, 13(4), 319–343.

11. Evans, J. (2004). Making a difference? Education and ‘ability’ in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 10, 95–108.

12. Evans, J., Davies, B., & Wright, J. (2004). Body knowledge and control: Studies in the sociology of physical education and health. London, England: Routledge.

13. Falk, E. (1903). Friskgymnastik I: anteckningar från skilda källor [Pedagogical gymnastics I: notes from different sources]. Stockholm, Sweden: Palmquist AB.

14. Falk, E. (1913). Gymnastikfrågan vid Stockholms folkskolor [The question of pedagogical gymnastics in Stockholm’s elementary schools]. Stockholm, Sweden: Palmquists AB.

15. Fernandez, I. L. (2009). The social, political and economic contetxs to the evolution of Spanish physical educationalists (1874–1992). International Journal of History in Sport, 26(11), 1630–1658.

16. Folkhälsoinsititutet. (2011). Barns och ungas hälsa. Kunskapsunderlag för Folkhälsopolitisk rapport [Health of children and young people: A knowledge base for public health policy report] (Delrapport: R 2011:14). Östersund, Sweden: Folkhälsoinsititutet.

17. Forsman, C., & Moberg, K. (1990). Rytmikens inträde i den svenska gymnastiken [The introduction of rhythmics in Swedish gymnastics]. Idrottslärarlinjen 1990:6 [Physical education teacher program 1990:6]. Stockholm, Sweden: Gymnastik- och idrottshögskolan.

18. Gard, M., & Wright, J. (2001). Managing uncertainty. Obesity discourse and physical education in a risk society. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 20(6), 535–549.

19. Gard, M., & Wright, J. (2006). The obesity crises. London, England: Routledge.

20. Green, K. (2008). Understanding physical education. London, England: Sage.

21. Hardman, K., & Green, K. (2011). Contemporary issues in physical education. Maidenhead, England: Meyer & Meyer Sport.

22. Idrottshögskolan, Lärarutbildningsnämnden. (2002). Kursplan för “Hälsa och miljö I, 5 p”, fastställd 2002-06-14 [Curriculum for Health and Environment I, 5 credits, determined in 2002-06-14]. Stockholm, Sweden: Idrottshögskolan.

23. Idrottshögskolan, Lärarutbildningsnämnden. (2003). Kursplan för “Hälsa och miljö II, 5 p”, fastställd 2003-03-26 [Curriculum for Health and Environment II, 5 credits, determined in 2003-03-26]. Stockholm, Sweden: Idrottshögskolan.

24. Kirk, D. (2010). Physical education futures. London, England: Routledge.

25. Kirk, D., & Macdonald, D. (2001). The social construction of PETE in higher education: Towards a research agenda. Quest, 53, 440–556.

26. Kirk, D., Macdonald, D., & Tinning, R. (1997). The social construction of pedagogic discourse in physical education teacher education in Australia. Curriculum Studies, 8(2), 271–298.

27. Korsgaard, O. (1989). Fighting for life: From Ling and Grundtvig to Nordic visions of body culture. Scandinavian Journal of Sports Sciences, 11(1), 3–7.

28. Laine, L. (1989). In search of a physical culture for women – Women’s movement and culture in everyday life; Elli Björstén’s heritage today. Scandinavian Journal of Sports Sciences, 11(1), 15–27.

29. Lindhard, J. (1926). Über den Einfluss einiger gymnastischen Stellungen auf den Brustkast [On the effect of some gymnastic positions on the thorax]. Skandinavische Archiv für Physiologie, 47, 188–261.

30. Lindroth, J. (1993/1994). The history of Ling gymnastics in Sweden. A research study. Stadion, 19/20, 164–177.

31. Lindroth, J. (2004). Ling – från storhet till upplösning i svensk gymnastikhistoria 1800–1950 [Ling – from grandness to decline in Swedish history of gymnastics]. Eslöv, Sweden: Brutus Östlings bokförlag Symposion.

32. Ling, P. H. (1979). Gymnastikens allmänna grunder [The general foundation of gymnastics] (Facsimile ed.). Stockholm, Sweden: Svenska Gymnastikförbundet. (Original work published 1840)

33. Ljunggren, J. (2000). The masculine road through modernity: Ling gymnastics and male socialisation in nineteenth-century Sweden. In A. Mangan (Ed.), Making European masculinities: Sport, Europe, gender. European Sports History Review, 2, 86–111.

34. Lundquist Wanneberg, P. (2004). Kroppens medborgarfostran. Kropp, klass och genus i skolans fysiska fostran 1919–1962 [The schooling of the body. Body, class and gender] (Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm, Sweden, Stockholm University.

35. Lundvall, S., & Meckbach, J. (2003). Ett ämne i rörelse – gymnastik för kvinnor och män i lärarutbildningen vid Gymnastiska Centralinstitutet/Gymnastik- och idrottshögskolan under åren 1944–1992 [A subject in motion – gymnastics in the PETE program at the Royal Central Institute of Gymnastics/GIH during the period 1944–1992] (Doctoral dissertation). Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden.

36. Lundvall, S., & Meckbach, J. (2008). Mind the gap – Physical education and health and the frame factor theory as a tool for analysing educational settings. Physical Education and Sports Pedagogy, 13(4), 345–364.

37. Lundvall, S., & Meckbach, J. (2012). Från gymnastikdirektör till lärare i idrott och hälsa. In H. Larsson & J. Meckbach (Eds), Idrottsdidaktiska utmaningar [Didactic challenges in sports pedagogy] (pp. 250–265). Stockholm, Sweden: Liber Förlag.

38. Macdonald, D., & Hay, P. (2010). Evidence for the social construction of ability in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 15(1), 1–18.

39. Mangan, J. A. (1981a). Athleticism in Victorian and Edwardian public schools. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

40. Mangan, J. A. (1981b). Social Darwinism, sport and English upper class education. Stadion, 7(1), 93–116.

41. McKenna, J., & Riddoch, C. (2003). Perspectives on health and exercise. New York, NY: Palgrave.

42. McKenzie, T. L., Alcaraz, J. E., Sallis, J. F., & Faucette, F. N. (1998). Effects on of a physical education program on childrens’ manipulative skills. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 17, 327–341.

43. Morgan, J. M. (2006). Philosophy and physical education. In D. Kirk, D. Macdonald, & M. O’Sullivan (Eds.), The handbook in physical education (pp. 97–108). London, England: Sage.

44. Morgan, R. E., & Adamson, G. T. (1961). Circuit training (2nd ed.). London, England: Bell.

45. Morgan, W. P. (2000). Prescription of physical activity: A paradigm shift. Quest, 53, 366–382.

46. O’Sullivan, M., Bush, K., & Gehring, M. (2002). Gender equity and physical education: A USA perspective. In D. Penney (Ed.), Gender and physical education: Contemporary issues and future directions (pp. 163–189). London, England: Routledge.

47. Palmblad, E., & Eriksson, B. E. (1995). Kropp och politik: Hälsoupplysningen som samhällspegel från 30-tal till 90-tal [Body and politics: The health enlightenment from the 1930s to the 1990s as a mirror of society]. Stockholm, Sweden: Carlssons.

48. Pfister, G. (2003). Cultural confrontations: German Turnen, Swedish gymnastics and English sport – European diversity in physical activities from a historical perspective. Culture, Sport, Society, 6(1), 61–91.

49. Pühse, U., & Gerber, M. (2005). International comparison of physical education: Concepts, problems, prospects. Aachen, Germany: Mayer & Mayer.

50. Quennerstedt, M., Öhman, M., & Ericson, C. (2008). Physical education in Sweden: A national evaluation. Education-line. Retrieved from htt://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/

51. Sandblad, H. (1985). Olympia och Valhalla: Idéhistoriska aspekter av den moderna idrottsrörelsens framväxt. Stockholm: Almkvist och Wicksell.

52. Sandell, K., & Sörlin, S. (2008). Friluftshistoria: Från ”härdande friluftsliv” till ekoturism och miljöpedagogi [The history of outdoor life: From ‘strengthening outdoor life’ to eco tourism and environmental pedagogy]. Stockholm, Sweden: Carlssons.

53. Schantz, P. (2002, September). Environment, sustainability and the agenda for physical education. International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education (ICSSPE) Bulletin, 36, 8–9.

54. Schantz, P. (2006). Rörelse, hälsa och miljö: Utmaningar i en ny tid [Movement, health and environment – challenges in a new time]. Svensk Idrottsforskning, 3, 4–7.

55. Schantz, P. (2009). Om Lindhardskolan och dess betydelse i ett svensk perspektiv [The Lindhard school and its influence from a Swedish perspective]. In A. Lykke Poulsen, E. Trangbæck,

56. K. Jørgensen, & N. Nordsborg (Eds.), Forskning i bevaegelse: Et nytt forskningsfelt I et 100-årigt perspektiv [Research in human movement: A new research field in a 100-year perspective] (pp. 137–167). Köpenhamn, Denmark: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, Köpenhamns Universitet.

57. Schantz, P., & Lundvall, S. (forthcoming). Changing perspectives on physical education in Sweden: Implementing dimensions of public health and sustainable development. In M.- K. Chin & C. R. Edginton (Eds.), Physical education and health: Global perspectives and best practice. Urbana, IL: Sagamore.

58. Schantz, P. G., & Nilsson, J. (1990). Skolans kroppsövningar i obalans: Tillför en konstnärlig dimension [Imbalance in the school’s physical exercises – add an artistic dimension]. Tidskrift i Gymnastik, 6, 10–17.

59. Siedentop, D. L. (2009). National plan for physical activity: Educational sector. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 6(2), 168–180.

60. Skolinspektionen. (2010). Mycket idrott och lite hälsa. Skolinspektionens rapport från den flygande tillsynen i idrott och hälsa [Lot of sports and little health. Report from the flying inspection of the Swedish Schools Inspectorate] (Report 2010:2037). Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish Schools Inspectorate.

61. Smith, A., & Biddle, S. (2008). Youth physical activity and sedentary behavior challenges and solutions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

62. Söderberg, B. (1996). P.H. Ling i gungning. En strid på 1940-talet om Linggymnastikens förflutna [P.H. Ling under attack. A battle during the 1940s concerning the past of Ling gymnastics]. In J. Lindroth, Idrott, Historia och Samhälle, Svenska Idrottshistoriska föreningens årsskrift [The annual publication of the Swedish Sports History Association]. SVIF-Nytt, 4, 100–117.

63. Thedin Jakobsson, B. (in press). What makes teenagers continue? A salutogenic approach to understanding youth participation in Swedish club sports. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy.

64. Tinning, R. (2010). Pedagogy and human movement: Theory, practice and research. London, England: Routledge.

65. Tolgfors, B. (1979). Historik över GIH-utbildningarnas historia under senaste 50-årsperioden [History of GIH – the Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences’ educational programs during the last 50-year period]. Tidskrift i Gymnastik, 9, 323–330.

66. Trost, S. (2006). Public health and physical education. In D. Kirk, D. Macdonald, & M. O’Sullivan (Eds.), The handbook in physical education. London, England: Sage.

67. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (1996). Physical activity and health. A report of the Surgeon General (Executive summary). Washington, DC: Author.

68. World Health Organization. (2002). How much physical activity needed to improve and maintain health? Retrieved from www.who.int/hpr/physactiv/pa.hoe.much.html/

69. Wright, J. (1996). Mapping discourses of physical education: Articulating a female tradition. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 28(3), 331–351.

70. Wright, J., & Macdonald, D. (2011). Young people, physical activity and the everyday. London, England: Routledge.