CEOs in Headphones

Submitted by Martin J. Greenberg and Thom Park, Ph.D.

INTRODUCTION

A “coach” is dictionary defined as one who trains intensively by instruction, demonstration, and practice. That dictionary definition may have defined the coach of old, but does not recognize the current job environment and employment conditions of the modern-day college coach. The college coach of today is required not only to be an instructor, but also act as a fund raiser, recruiter, academic adviser, public figure, budget director, television, radio and internet personality, alumni glad-handler, and any other role that the university’s athletic director or president may direct him to do. Sports sociologists would opine that college coaches suffer from a condition known in the social science discipline as ‘role strain;’ that is, they have far too many roles to fill at very high levels of performance.

Coaching is a high-profile and high-risk position where every move and moment is surrounded by stress, and every decision, whether on or off the field, is subject to second-guessing and scrutiny and may often be the subject of a vicious public debate. Job security is as fleeting as the last seconds of a basketball victory in an environment where employment contracts are broken as easily as made.

Twenty-five years ago the average tenure of a Division 1A Head Football Coach was about 2.8 years. Nothing has changed. The first day on the job must often be spent planning for the last day, as the back end of the contract, i.e. termination provisions, may be more important than the compensation package. Job continuance is often conditioned on winning because wins are the equivalent of the bottom line — putting fans in the stands, selling enhanced seating, bolstering alumni contributions, generating lucrative TV and cable contracts, qualifying for Bowl competition, and persuading recruits to accept scholarships.

It is no wonder why big time college coaches are compensated the way they are — the job environment dictates the high compensation level.

CEOs IN HEADPHONES

Today’s major college coaches are CEOs in Headphones. Components of their compensation in some ways equate to the CEOs of private or publicly held companies. Compensation packages can include a signing bonus, base pay and supplemental payments, loans, supplemental insurance, deferred compensation, annuities, memberships, company car, tuition, and golden parachute provisions, to name a few. It has been reported that during the period 2007 through 2011, CEO pay rose 23%, while in the same period college coaches’ pay increased 44%.

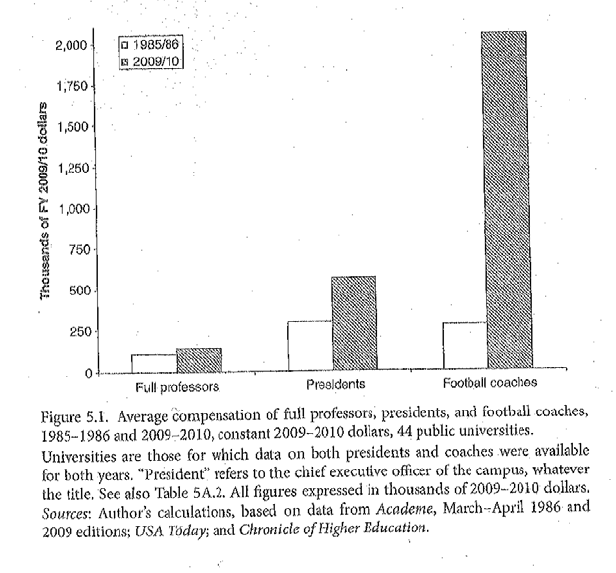

Coaches’ salary inflation is part of the athletics arms race and has run rampant. In a recent study, college coaching salaries rose more than 750% during the 24-year period between 1985 and 2010, while during the same period, pay for full professors increased 32%, and the pay for college presidents increased 90%.

In a survey conducted by the Knight Commission in 2009, 85% of university presidents believed that college football coaches’ compensation is excessive and identified escalating coaching salaries as the single largest contributing factor to the unsustainable growth of athletic spending.

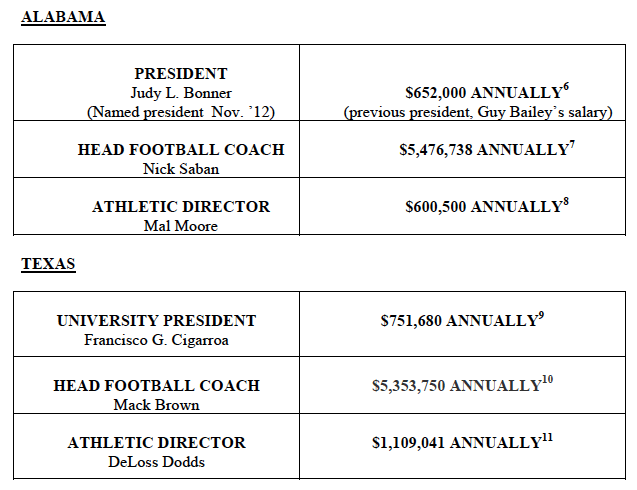

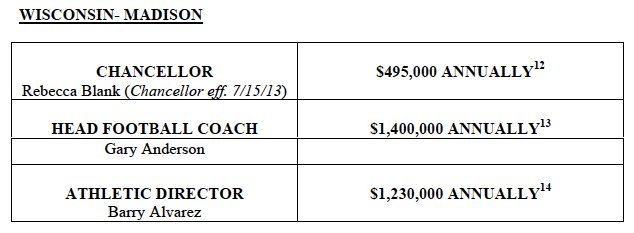

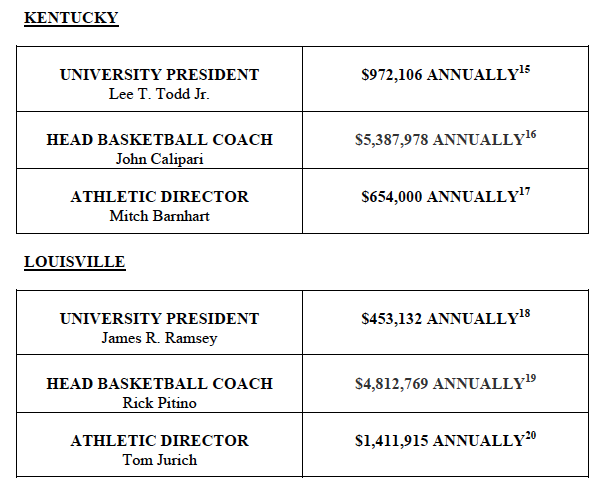

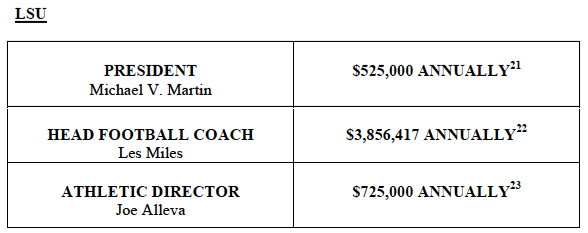

In most instances the college coach is the highest paid state employee of a public institution, and the compensation package can be five to ten times the amount paid university presidents and athletic directors. What follows is a comparison of reported, but unverified, compensation packages of presidents, head football coaches, and athletic directors at several major state schools:

COACH’S COMPENSATION

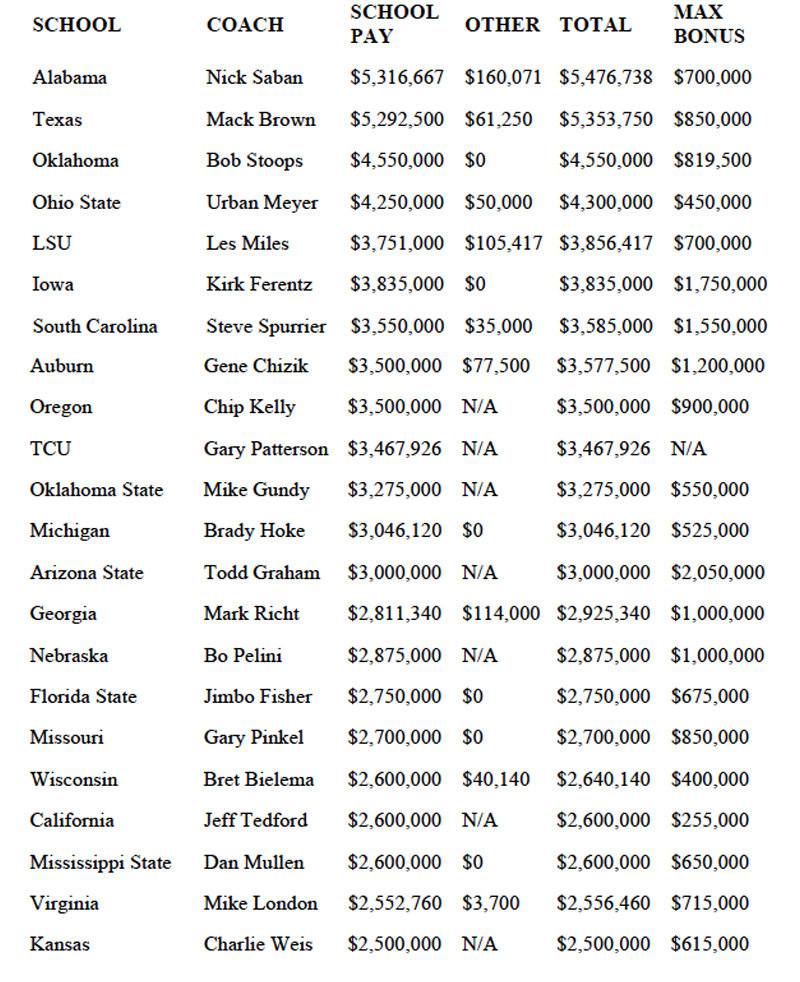

It was reported by USA Today that the average 2012 annual compensation for major college football head coaches is $1.64 million, up nearly 12% over the 2011 season, and more than 70% since 2006. Alabama’s Nick Saban and Texas’ Mack Brown are the highest paid football coaches.

The conference with the highest average compensation for its head football coaches is the Big 12, whose ten coaches are earning slightly less than $3 million a year. What follows, according to USA Today, are football coaches who earned at least $2.5 million for the 2012 football season:

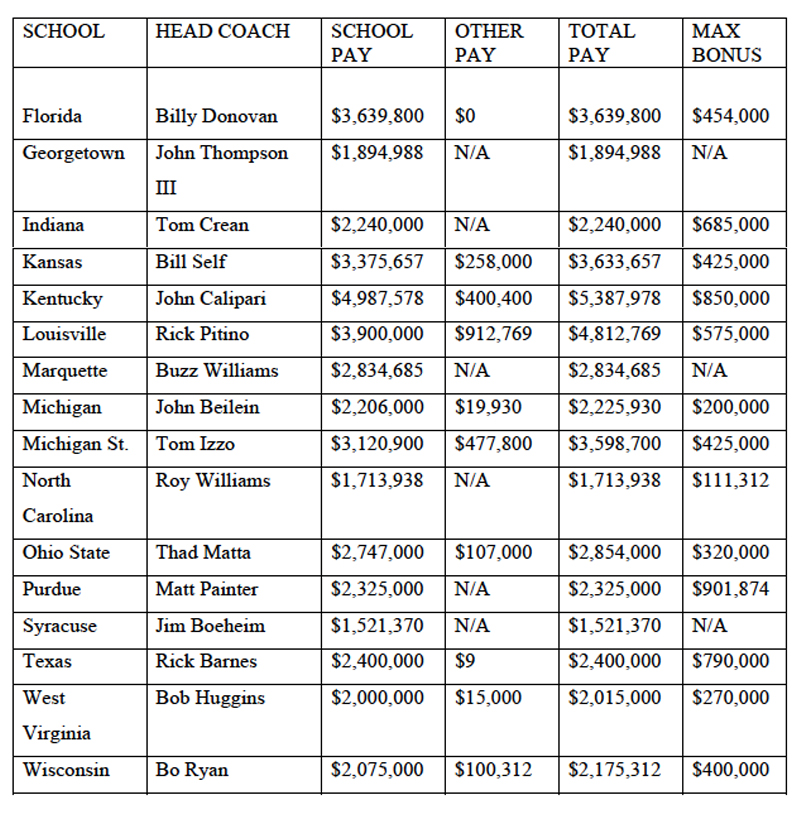

Similarly, the reported compensation packages, according to USA Today, of coaches for

major basketball programs are also healthy:

NCAA College Basketball Coaches’ Salary Database

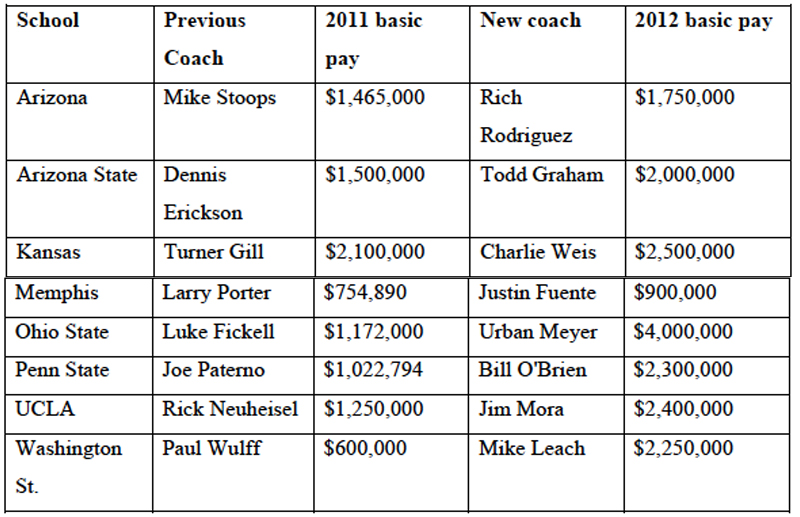

Among the 120 Bowl Division schools, 25 had made coaching changes for the 2012 season. Many of those universities who have made changes have had to dramatically increase their compensation packages in order to obtain their newly appointed coach.

OVERCOMPENSATED

So is a major college football coach overcompensated? There is no business like show business except $portsBiz. One in a million deserves more than a million. Compensation packages are market driven, and today the market is overly aggressive. The coaches’ market may not even be based on Moneyball Metrics, i.e. wins, tournament appearances and wins, revenue, attendance, rankings, or donations. A successful collegiate football program has many economic as well as non-economic benefits to the University, including driving alumni contributions and student enrollment, creating revenue streams that support non-revenue sports, and the psychic income of being “Big Time.” In many instances these escalating compensation packages are paid for through multi-million dollar paydays from conference broadcast and multi-media contracts, rabid fans willing to pay the price for enhanced seating, marketing deals with companies willing to sponsor the athletic initiative, apparel companies desirous of having their logo on athletes’ uniforms, and semi-autonomous booster clubs.

No comparative faculty member vs. athletic coach compensation analysis has ever taken into consideration the many other variables in the job life of the coach versus the job life of a faculty member. Some of these considerations and mitigating factors are job tenures, hours worked, stress endured, measured job pressure, frequency of termination versus tenured jobs, fractured unvested pension plans, lateral moves to advance, and the list goes on. By any measure, such compensation analyses versus the public perception of the coaches’ compensation are gravely misunderstood. College coaches earn absolutely every penny they make.

Universities are tasked with education, academic research, and public service to their communities. Coaches’ compensation packages that so dramatically dwarf the compensation packages of administrators and our best professors seems out of proportion. Even presidents and trustees of major universities can fall prey to the glamour of a winning season or a BCS bowl bid. In the context of amateurism, college athletes are not paid and big money can be targeted for a big name coach. The compensation packages of today’s college coaches are indicative of the high premium American society puts on the athletic enterprise. A successful college coach is a limited commodity, and the compensation packages are simply a function of supply and demand.

PACKAGE

For years we have negotiated the components of coaches’ compensation in reference to “The Package.” The Package included:

I. Institutional Pay + Fringe Benefits

1. Salary

2. Life and health insurance

3. Vacation with pay

4. TIAA I CREF

6. Tuition waivers

6. Complimentary tickets

7. Annuity — longevity bonus

8. Contractual Bonuses

II. Outside income

1. Shoe, apparel, and equipment endorsements

2. Television, radio, and Internet shows

3. Speaking engagements

4. Personal or public appearances

5. Summer camps

III. Perquisites

1. Housing allowances

2. Membership in clubs

3. Business opportunities

4. Automobile usage

5. Dependent travel

6. Moving allowances

7. Additional insurance

8. Interest-free loans

The coach in most instances was permitted to separately contract for outside income sources. Today this is mostly university controlled and the coach receives institutional pay, plus fringe benefits, plus a talent fee or personal service fee that encompasses what previously was outside income but now is under institutional control, plus the perquisites as part of a total compensation package.

FINANCIAL ENGINEERING

The modern day coach financial structuring looks more like a CEO of a publicly traded or private company, with many new financial instruments and packages coming to the negotiation table including:

1. Signing bonuses

2. Retention, continuation, longevity bonuses

3. Up step life insurance provisions

4. Deferred compensation

5. Buyout of previous employer

6. Post-coaching employment

7. Interest free or forgivable loans

8. Retirement plans

9. Annuity

10. Expense account

11. Relocation payment

12. Disability payment

13. Entrepreneurial sharing

1. SIGNING BONUSES

BROWN – University of Texas-Austin: Special One Time Payment. Within 30 days of his execution of this agreement, Brown will receive a Special One Time Payment of $100,000.

JOHNSON – Georgia Tech: Signing Bonus. The Association agrees to pay Coach a onetime bonus of Two Hundred Thousand dollars ($200,000.00) within thirty (30) days of the signing of this employment contract.

MILLER – University of Arizona: Signing payment. As a consideration for the execution of this Contract, University will pay Coach one Million and 00/100 Dollars ($1,000,000) upon execution hereof.

MUSCHAMP – University of Florida: Signing Incentive. The Association shall pay to the Coach a Seven Hundred Fifty Thousand dollars ($750,000.00) signing incentive to be paid, subject to applicable taxes and withholding, upon execution and delivery of this Agreement by both parties.

O’LEARY – University of Central Florida: The coach shall be entitled to a signing bonus of $150,000 effective July 1, 2006, payable on next regularly scheduled Association pay period.

DYKES – University of California-Berkeley: Coach shall receive a one-time signing bonus of $594,000 on or before February 15, 2013.

2. RETENTION, CONTINUATION, LONGEVITY BONUSES

BARNES – University of Texas/Austin: If Barnes is head coach on March 31, 2010, a special payment of $1,000,000 will be made to Barnes. If Barnes is head coach on March 31, 2013, a second special payment of $1,000,000 will be made to Barnes.

CALIPARI – University of Kentucky: Retention Incentive. In addition to the above stated competitive and academic-based incentives, a retention incentive to encourage Coach to remain with the University shall be provided. University agrees to pay Coach a retention incentive if Coach remains in the employment of the University on each of the following dates:

March 31, 2014 (Bonus = $750,000), March 31, 2015 (Bonus = $1,000,000) and March 31, 2016 (Bonus + $1,250,000). Said bonuses to be paid within ten (10) days of the achievement of the applicable bonus.

DANTONIO – Michigan State University: 3.10. Contingent Annual Bonus. The University shall pay to Coach an annual bonus of Two Hundred Thousand Dollars ($200,000), provided that the Coach has served continuously as the Program Head Coach for the twelve consecutive months immediately preceding July 1st of the year in which the bonus will be paid. Such bonus will vest on the first business day following the conclusion of the twelve-month period and will be paid to Coach on or before the end of the month in which the bonus vests.

3.11 Contingent Bonus: In the event the Coach continuously serves as the Program Head Coach through January 15, 2014, the University shall pay the Coach, on or before March 9, 2014, the amount of Two Million Dollars ($2,000,000).

HOKE – University of Michigan: Stay Bonus. The Head Coach shall earn a bonus of $500,000 for each full Contract Year he remains employed as head football coach by the University. The first three years of the stay bonus will not be vested and payable to the Head Coach unless he remains continuously employed as the head football coach by the University through the conclusion of Contract Year Three (December 31, 2013), at which time the first three years of the stay bonus shall vest and be payable to the Head Coach within thirty (30) days. The second three Contract Years of the stay bonus will not be vested and payable to the Head Coach unless he remains continuously employed as the head football coach by the University through the conclusion of Contract Year Six (December 31, 2016), at which time the second three Contract Years of the bonus shall vest and be payable to the Head Coach. The University shall pay any vested stay bonus within thirty (30) days of vesting date.

JONES – University of Cincinnati (Terminated): Retention Bonus. Coach shall earn a retention bonus in the amounts set forth below provided he is still employed as Head football Coach on the date indicated:

January 15, 2012 – $100,000

January 15, 2013 – $0

January 15, 2014 – $0

January 15, 2015 – $300,000

January 15, 2016 – $300,000

January 16, 2017 – $300,000

MEYER – Ohio State University: 3.11. Ohio State shall pay Coach the following sums if he is employed as Head Football Coach on the following dates:

a) Four Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($450,000) — January 31, 2014, payable within thirty (30) days following such date;

b) Seven Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($750,000) — January 31, 2016, payable

within thirty (30) days following such date;

c) One Million Two Hundred Thousand Dollars ($1,200,000) — January 31, 2018,

payable within thirty (30) days following such date.

MILLER – University of Arizona: Retention Fund. At the end of each Contract Year, University will credit Three Hundred Thousand and 00/100 ($300,000) Dollars to a Retention Fund.

SABAN – University of Alabama: Contract Year Completion Benefit. If Employee is then employed as Head Football Coach of the University as of the dates set out below, Employee (or a corporate entity designated by the Employee) shall receive on that date the Contract Year Completion Benefit set out next to said dates:

January 15, 2012 $1,600,000 (upon completion of 5th year)

January 15, 2015 $1,700,000 (upon completion of 8th year)

January 15, 2018 $1,700,000 (upon completion of 11th year)

SELF – University of Kansas — Retention Payment Agreement:

Retention Payment. If Head Coach serves continuously as head basketball coach through March 31, 2013, or sooner as provided for herein, in addition to all other payments as found in the Employment Agreement dated April 1, 2008, Athletics shall pay to Head Coach on March 31, 2013, an after-tax sum of $2,114,575 (Initial Payment). That is, taking in account all state and federal tax liabilities Head Coach will owe with respect to the Initial Payment, Head Coach shall receive the net amount of $2,114,575. Athletics shall credit a separate account in favor of Head Coach with such annual amounts so that if Head Coach serves continuously as head men’s basketball coach through March 31, 2013, or sooner as provided for herein, Head Coach shall receive, $2,114,575 on March 31, 2013 (being the sum of $371,525 + $371,525 + $371, 525 + $500,000 + $500,000). Beginning on April 1, 2013, for each full year thereafter that Head Coach serves continuously as head men’s basketball coach through March 31, 2018, Head Coach shall be entitled to receive the after-tax sum of $500,000 per annum through March 31, 2018. Athletics shall credit a separate account in favor of Head Coach with such annual amounts so that if Head Coach serves continuously as head men’s basketball coach through March 31, 2018, Head Coach shall be entitled to receive $2,500,000 (second payment) on March 31, 2018 (being $500,000 multiplied by five years). That is taking into account all State and Federal tax

liabilities Head Coach will owe with respect to the second payment, Head Coach shall receive the net amount of $2,500,000 for the period April 1, 2013, through March 31, 2018. Vesting. Except as specifically described elsewhere in this Agreement, so long as Head Coach is serving as head basketball coach, these payments to Head Coach will vest on an annual basis so that the after-tax sum of $371,525 shall vest for the benefit of Head Coach on March 31, 2009, 2010 and 2011, and the after-tax sum of $500,000 shall vest for the benefit of Head Coach on March 31, 2012, and each year thereafter through March 31, 2018, during the term of this Agreement and Head Coach’s employment. This amount, although vesting on an annual basis, will not be paid to Head Coach, except as otherwise provided for herein until March 31, 2013 (Initial Payment due) and March 31, 2018 (Second Payment due).

STOOPS – University of Oklahoma: Annual Stay Benefit. On October 1, 2009 and on July 1 of each contract year thereafter (“Annual Date”) the University shall pay Coach within 30 days of that date the annual sum of Seven Hundred Thousand Dollars ($700,000) (“Annual Sum”) subject to the following provisions. Coach will be entitled to each Annual Sum if Coach remains employed at the University as Head Football Coach through each Annual Date outlined above subject to the following provisions. If Coach is no longer employed with the University on or prior to each Annual Date, then Coach shall be entitled to a pro rata portion of the Annual Sum (the “Pro Rata Portion”) based on Coach’s completed months of service with the University for that specific contract year. However if Coach voluntarily terminates employment on or prior to any Annual Date and assumes another coaching position, then Coach shall forfeit all of his right to the Annual Sum whether accrued or unaccrued. Notwithstanding the foregoing, if Coach voluntarily terminates due to David L. Boren no longer serving as the University’s President, then Coach may voluntarily terminate employment as Head Football Coach and assume another coaching position without forfeiting his Pro Rata Portion of the Annual Sum.

Additional Stay Benefit. If Coach remains employed at the University through January 1, 2011, University will contribute sufficient amounts so that an aggregate sum of Eight Hundred Thousand Dollars ($800,000) (“Stay Benefit”) will be accumulated as of such date in the existing or new tax-qualified or authorized employee retirement programs or plans (the “Plans”) established by the University for the benefit of Coach under IRS Section 401(a), 403(b), 415(m) and 457(b) pursuant to paragraph IV.D of the previous Contract between the parties which had an effective date of January 1, 2007. Coach will be entitled to the Stay Benefit if Coach remains employed at the University as Head football Coach through January 1, 2011, subject to the following provisions. If Coach is no longer employed with the University on or prior to January 1, 2011, then Coach shall be entitled to a pro rata portion of the Stay Benefit (the “Pro Rata Portion”) based on Coach’s completed months of service with the University from January 1, 2009 through January 1, 2011 divided by 24 (number of months in the period from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2011). However, if Coach voluntarily terminates employment on or prior to January 1, 2011 and assumes another coaching position, then Coach shall forfeit all of his right to the Stay Benefit whether accrued or unaccrued. Notwithstanding the foregoing, if Coach voluntarily terminates due to David L. Boren no longer serving as the University’s president, then Coach may voluntarily terminate employment as Head Football Coach and assume another coaching position without forfeiting his Pro Rata Portion of the Stay Benefit.

CHRISTIAN – Ohio University: At the conclusion of each season, Head Coach shall receive a longevity bonus of $100,000.

3. UP STEP LIFE INSURANCE PROVISIONS

DANTONIO – Michigan State University: 3.4.6. Insurance benefits consisting of (a) a Two Million Dollar ($2,000,000) term life insurance policy and (b) a disability policy to provide, in the event of the Coach’s disability, a monthly benefit amount of $6,000 for sixty (60) months, including a cost of living annual benefit adjustment and a lump sum distribution at the end of sixty (60) months.

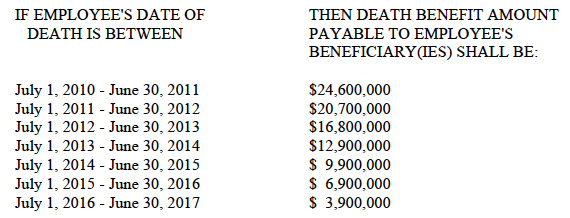

PITINO – University of Louisville: Employer shall, subject to approval for coverage by an appropriate insurance carrier (which approval Employer shall use its best efforts to obtain), be the owner of a term life insurance policy on the life of Employee, having a face amount of $24,600,000. Employer shall pay all premiums needed to keep said policy in force through June 30, 2017. in the event of Employee’s death during the Term of this Contract and amounts are payable pursuant to such policy, a life insurance death benefit in the amount set forth in the following schedule shall be paid to such beneficiary(ies) as Employee or his assignee shall designate to Employer in writing:

insurance policy shall lapse effective July 1, 2017, regardless of whether the policy is surrendered by Employer at that time. Provided, however, in the event that, prior to July 1, 2017, Employee becomes so disabled as not to be capable of performing his duties hereunder for a period of six months or more and Employer has been unable to purchase a policy of long-term disability insurance as provided in Section 6.2 hereof, then Employer shall assign to Employee, and Employee shall have the right to designate the beneficiary(ies) for the death benefit payable on such amount of said policy as is determined pursuant to Section 6.2 hereof. Employee (or his assignee) shall have the right to designate the beneficiary(ies) for the death benefit payable on behalf of Employee as outlined in this Section 3.1.14 above, and Employer shall have the right to designate the beneficiary(ies) for any death benefit proceeds payable from the policy in excess of the amount owed to Employee’s beneficiary(ies). If for any reason Employee (or his assignee) does not designate a beneficiary, such policy shall designate The Richard A. Pitino Revocable Trust u/a September 12, 2000, as beneficiary. Employee shall have the right to assign absolutely his rights, if any, under said life insurance policy until July 1, 2017. Notwithstanding the foregoing, if this Contract is terminated prior to June 30, 2017 (other than on account of Employee’s death or disability) either (i) by Employer for Just Cause, or (ii) by Employee other than by reason of Employer’s continued breach of this Contract (as described in Section 6.5), then the life insurance policy described in this Section 3.1.14 shall terminate.

SPURRIER – University of South Carolina: During the term of this Employment Agreement, the University shall pay the premiums necessary to provide Coach with life insurance benefits totaling Two Million Dollars ($2,000,000). Coach shall have the sole and exclusive right to designate any beneficiary. During the term of this Employment Agreement, the University shall pay the premiums necessary to provide Coach with disability insurance income totaling Two Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($250,000) annually until Coach reaches the age of 65.

CREAN – Indiana University: Supplemental Term Life Insurance. The University shall purchase a supplemental life insurance policy for Employee payable to a designated beneficiary up to a face value of twenty million dollars ($20,000,000) based on an annual premium of up to a maximum of fifteen thousand dollars ($15,000). For income tax purposes, the annual premium shall be grossed up to take in account all applicable Federal income, State income, Social Security, and Medicare withholding taxes. If University determines that this term life insurance cannot be reasonably purchased from a commercial company, the University will pay employee fifteen thousand dollars ($15,000) as a lump-sum at the beginning of each calendar year for Term of the Agreement. This amount shall be net of applicable Federal income, State income, Social Security, and Medicare withholding taxes.

KINGSBURY – Texas Tech University: The University will provide to Coach a term life insurance policy in the amount of $5,000,000 at no cost to Coach during the term of the Agreement.

4. DEFERRED COMPENSATION

HOKE – University of Michigan: Deferred Compensation. In addition to the standard fringe benefits provided pursuant to Section 3.03(a) hereof, effective January 12, 2011, and during the remainder of the Term of this Agreement, the University shall establish and maintain a “Deferred Compensation Account” on its financial record to record the deferred compensation benefit earned by and payable to the Head Coach pursuant to this section. This provision is established as an ineligible nonqualified deferred compensation arrangement for the Head Coach’s benefit in accordance with Section 457(f) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”).

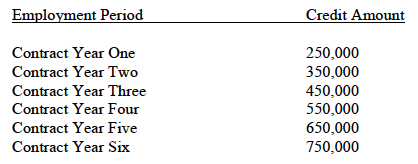

(i) Provided that the Head Coach is employed as head football coach of the University football team during the “Employment Period” indicated below, the University shall credit (add to) the Deferred Compensation Account equal monthly payments of one-twelfth of the year “Credit Amount” as follows (which amounts shall vest pursuant to the vesting and forfeiture provisions of subsections (iii) and (iv) below and be credited at the end of each month on a pro-rata basis:

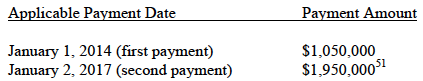

(ii) Subject to the vesting and forfeiture provisions in subsections (iii) and (iv) below, the University shall debit (subtract from) the Deferred Compensation Account and pay the Head Coach (or his beneficiary) the following amounts within thirty (30) days after the “applicable payment dates”:

MARSHALL – Wichita State University: If Mr. Marshall completes the 2011-2012 season, he will receive a one-time payment of Five Hundred Fifty Thousand and no/1.00 Dollars ($550,000.00); provided however, that should Mr. Marshall not complete the 2011-2012 season because of circumstances for any reason, Mr. Marshall will receive a one-time payment of Four Hundred Twenty-Five Thousand and No/1.00 Dollars ($425,000.00).

Beginning on April 16, 2012, a new annuity will be initiated for the remaining term of the contract at One Hundred Twenty-Five Thousand and No/1.00 Dollars ($125,000.00) per year, said amount to vest as of the completion of each successive basketball season. The total vested amount of the annuity will be paid at the conclusion of every fourth season (“Payout Year’) that Mr. Marshall is employed by the ICAA, i.e., paid at the completion of the 2015-16 season, completion of the 2019-20season, etc; provided, however, if Mr. Marshall were to leave the employment of the ICAA for any reason at any time other than a Payout Year, he shall receive the total vested amount at that time.

PINKEL – University of Missouri: Deferred Compensation. The University agrees to annual deposit to a Fund, which Fund shall be owned, maintained and controlled by the University, within fifteen days of January 1 of each year under the term of this contact, the sum of Two Hundred Thousand Dollars ($200,000.00).

PITINO – University of Louisville: Employer will maintain a deferred compensation account in Employee’s name to evidence amounts credited pursuant to Section 3.2.1. Amounts credited to Employee’s account pursuant to Section 3.2.1, adjusted by the amount of any earnings losses, are referred to herein as the “Account.” The Account shall be deemed to be invested by Employer so that the Account will be increased or decreased at least monthly by the earnings or losses on such deemed investment until the Account balance has been fully paid to Employee or Employee’s beneficiaries or is otherwise forfeited pursuant to the Contract. Employee may suggest the deemed investment of the Account from investment options which will be provided for Employee’s review not less frequently than annually by Employer. However, Employer is not required to honor in any way such suggestions by Employee, and Employer shall have sole discretion with respect to any deemed investment decision related to the Account, until such time as the Account is paid to Employee or Employee’s beneficiaries or is otherwise forfeited pursuant to this Contract. Employer shall provide to Employee at least annually (as of December 31 of each year starting with the period ending December 31, 2010) a schedule of the Account reporting the opening balance of the Account and all amounts, including earnings or losses, credited or debited to the Account during the reporting period and any distributions with regard to the Account during the reporting period.

The Account will be credited in the amount of: (i) Nine Hundred Thousand Dollars ($900,000) on July 1, 2010, (ii) Nine Hundred Thousand Dollars ($900,000) on July 1, 2011, and (iii) Nine Hundred Thousand Dollars ($900,000) on July 1, 2012.

CREAN – Indiana University: Deferred Compensation. Commencing on July 1, 2012,during the remainder of the term, the Employee will be eligible to earn deferred compensation at an annual rate of Five Hundred Sixty-Six Thousand Two Hundred Fifty Dollars ($566,250.00) “Deferred Compensation”). Deferred Compensation will be earned by the Employee on a prorated basis during the calendar year, with payment of such compensation deferred until thirty (30) days after the end of the calendar year. During any period of deferral, any Deferred Compensation will remain part of the University’s general assets, will not be deposited in a separate account, and will not bear interest. If the Employee remains employed with the University through December 31 of a calendar year during which Deferred Compensation accrues, the Employee shall vest in the Deferred Compensation on December 31 and shall be paid the Deferred Compensation, without interest, within thirty (30) days thereafter. In the event of termination of the Employee’s employment with the University for any reason prior to December 31, the Employee shall vest in the Deferred Compensation earned through the date of termination and shall be paid the Deferred Compensation, without interest, within thirty (30) days after the date of termination. By way of example, if the Employee remains employed with the University through December 31, 2012, the Employee will be entitled to $72,914.00 in Deferred Compensation, payable on or by January 30, 2013. For purposes of this Section 5.03, the term “termination” shall be interpreted to comply with the requirements of Internal Revenue Code 409A. In the event the Employee desires to modify the terms of this Section 5.03 for tax or other financial reasons, the parties agree to negotiate such modification in good faith and to use their respective best efforts to arrive at mutually acceptable terms. The Employee has been advised to engage legal and/or financial representatives regarding the tax implications of the Deferred Compensation. The Employee shall be solely responsible for any federal, state and local income taxes incurred by him as a result of the University’s payment of the Deferred Compensation.

5. BUYOUT OF PREVIOUS EMPLOYER

CHIZIK – Auburn University (Terminated): Repayment of Buyout from Previous Employment. Coach acknowledges that Auburn loaned him Seven Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($750,000.00) to satisfy the buyout provision of his contract with his previous employer. During the course of this contract, this debt will be forgiven in the amount of One Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($150,000.00) for each contract year completed under this Agreement such that the debt will be forgiven entirely. If Auburn terminates Coach for cause prior to December 31, 2013, or if Coach terminates his employment with the University for any reason other than disability or death prior to December 31, 2013, Coach will be responsible for paying University the balance remaining on this loan, with the amount owed for a partial year being determined on a pro rata basis (i.e., $12,500 per month). The remaining balance will be paid as follows: 50% within thirty (30) days of termination for cause by Auburn or termination by Coach; and 50% within one (1) year of termination for cause by Auburn or termination by Coach. Coach acknowledges that University also has the discretion to reduce the payments owed to Coach in Paragraph 18 in whole or in part as part of the repayment of this loan. If Auburn terminates Coach without cause prior to December 31, 2013, the balance remaining on loan will be forgiven by Auburn.

DOOLEY – University of Tennessee (Terminated): The University also agrees to pay (i) a total of $500,000, in two equal payments of $250,000 each, to Louisiana Tech University on Dooley’s behalf no later than June 1, 2010 and June 1, 2011; and (ii) a total of $286,782 to be paid to the Internal Revenue Service on Coach Dooley’s behalf as withheld taxes, $143,391 to be submitted to the Internal Revenue Service within thirty (30) days of the date on which each payment is submitted to Louisiana Tech University. The University will report total taxable value of the commitment in this Article II.C in the amount of $786,782. The sum set forth in this Article II.C. represents the total payment the University will make on behalf of Coach Dooley regardless of the amount of taxes actually due.

HOKE – University of Michigan: Buyout Payment. The Head Coach acknowledges that the University has agreed to pay on behalf of the Head Coach the sum of $1,000,000 to San Diego State University (“SDSU”) in order to satisfy the buyout terms of the Head Coach’s employment contract with SDSU. The University considers this payment as taxable wages for tax withholding and reporting purposes. Consistent with that determination, the University has made timely deposits with appropriate taxing authorities of all amounts required to be withheld as taxes with respect to the Head Coach as a result of making the SDSU settlement payment. The University has agreed to neutralize to zero (0) dollars the actual tax impact of the buy-out payment in order that the Head Coach not be unduly burdened or distracted in connection with the performance of his duties hereunder. It is the express intention of the parties that neither party benefit financially to the extent there is a difference between (i) the amount of withheld taxes and (ii) the amount of tax liability incurred by the Head Coach. With respect to this liability which is attributable to the University having made the buyout payment, the Head Coach must claim all deductions allowable under applicable tax laws, including this buyout payment. Therefore, as soon as practicable in 2012, the parties will review the Head Coach’s pertinent tax information, including his signed federal and state income tax returns for 2011, and either the Head Coach or the University will pay the other party, as the case may be, such amount as is necessary to effectuate this mutually desired benefit. The Head Coach represents and warrants to the University that he is not bound by or subject to any contractual or other obligation to SDSU or any other party that would be violated by his execution or performance of this Agreement.

ROBINSON – Oregon State University: Payment Toward Satisfaction of Coach’s Current Contract. University will pay Brown University or its designee the sum of $145,000 toward satisfaction of Coach’s obligations under his current contract with Brown University.

CREAN – Indiana University: Upon receipt of a copy of the terms of the Employee’s present contract with Marquette University that requires the Employee to pay Marquette liquidated damages upon the termination of the Employee’s contract, the University will pay the Employee the stated amount of liquidated damages; however, such amount shall not exceed six hundred fifty thousand dollars ($650,000). In the event this amount is deemed to be income, the Employee will be responsible for any associated tax consequences.

BIELEMA – University of Arkansas: The University will pay (using legally permissible funds) Coach’s former employer a sum not to exceed a total of One Million and No/100 Dollars ($1,000,000.00) if required under the terms of Coach’s employment contract with his previous employer. The University considers this payment to be taxable wages for tax withholding and reporting purposes. Consistent with that determination, the University will make timely deposits with appropriate taxing authorities of all amounts required to be withheld as taxes with respect to Coach as a result of making any such payment. The University will neutralize to zero (o) dollars the actual tax impact of such payment to enable you to avoid any undue burdens or distractions in connection with the performance of your duties as Head Football Coach at the University. With regard to the University’s commitment to undertake this obligation, we expressly agree and intend that the University or you will not benefit financially to the extent there is a difference between (a) the amount of withheld taxes and (b) the amount of tax liability incurred by you. With respect to this liability, which is attributable to the University making any such payment, you agree to claim all deductions allowable under applicable tax laws, including any applicable deductions relating to the amount paid by the University to satisfy any portion of your employment agreement with your previous employer. Depending on the timing of any such payment by the University, you and/or your advisors agree to review your pertinent tax information, including any signed federal and state income tax returns necessary, and either the University or you will pay the other party, as the case may be, such amount as is necessary to effectuate this mutually desired benefit. Coach represents and warrants to the University that his acceptance of the position of Head Football Coach and his performance of the duties of this position will not violate any other contract or obligation to any other party.

TUBERVILLE – University of Cincinnati: The Employment Agreement shall contain a provision which states that upon receipt by the University of satisfactory evidence that Coach has incurred a binding contractual buy-out obligation payable to Texas Tech University by accepting employment as the University’s Head Football Coach, and upon receipt of a copy of the invoice received by Coach from Texas Tech University for the same, the University shall issue a payment to Coach of the buy-out amount not to exceed $931,000. Coach understands and acknowledges that the $931,000 constitutes income to him under applicable State and Federal tax codes and will be subject to withholding.

6. POST – COACHING EMPLOYMENT

DANTONIO – Michigan State University: In the event the Coach continuously serves as the Program Head Coach through March 15, 2014, the Department will offer Coach a two-year contract within the Athletics Department at an annual salary rate of $200,000 following the conclusion of his employment as Program Head Coach. In this position, the Coach will perform duties within the area of University Advancement as assigned by the University President and Athletics Director. The terms of the contract will be consistent with the standard terms for administrative appointments within the Department. Coach will not be eligible for this postcoaching employment if he ceases to be the Program Head Coach in order to take a position coaching a professional football team or an intercollegiate football program other than the Program.

TRESSEL – Ohio State University (Terminated): Upon notice from Coach that he intends to terminate his employment under this agreement, Coach may request from Ohio State the opportunity to have a non-tenure track faculty position at Ohio State. If Coach makes such a request, and if Ohio State does not have “cause” to terminate this agreement under Section 5.1, then Ohio State shall make a non-tenure track faculty position available to Coach. Salary, benefits and other terms of employment for such non-tenure track faculty position shall be mutually agreed upon between Coach, the Department of Athletics and the appropriate academic unit. Upon execution of such an agreement, this agreement shall terminate. The non-tenure track faculty position shall have a term not to exceed five (5) years, and shall be re-evaluated at the conclusion of such term.

7. INTEREST-FREE OR FORGIVABLE LOANS

JONES – University of Cincinnati (Terminated): Loan. Within thirty (30) days of the approval of this Agreement by the Trustees of the University of Cincinnati, the University shall provide Coach with a Seven Hundred Thousand Dollars ($700,000) interest-free loan (the “Loan”). The Loan shall be forgiven by One Hundred Forty Thousand Dollars ($140,000) on January 1, 2011 or after the completion of any University bowl game of the 2010 football season, whichever is later. Commencing on February 1, 2012, the Loan balance shall be forgiven in equal monthly amounts over the remaining months of the Term pursuant to the terms of a promissory between the University and Coach.

The terms of the Loan are set forth in the Promissory Note (“Note”). Coach shall execute the Note within seven days of the approval of this Amendment by the University’s Board of Trustees. Coach understands and agrees that he shall be responsible for the payment of all taxes incurred as a result of the Loan and the monthly forgiveness of the Loan.

8. RETIREMENT PLANS

MEYER – Ohio State: For the period beginning September 1, 2012 and ending on January 31, 2013, Ohio State shall pay Coach Twenty Thousand Eight Hundred Thirty-Three Dollars ($20,833) in substantially equal monthly installments and in accordance with normal Ohio State procedures. In addition, Ohio State shall contribute Seven Hundred Thousand Dollars ($700,000) to the DC Plan on January 31, 2013 (or in more frequent installments as determined by Ohio State in its sole and absolute discretion). Notwithstanding the foregoing: (a) to the extent that the Code limits or prohibits such contributions from being made to the DC Plan, Ohio State shall contribute such amounts to a defined contribution plan that is a nonqualified deferred compensation plan; and (b) if Coach is not employed as Head Football Coach on January 31, 2013, the aggregate contribution to the plans described in this Paragraph 3.2(3) shall be equal to Seven Hundred Thousand Dollars ($700,000), multiplied by a ratio, the numerator of which is the number of days Coach was employed as Head Football Coach for the period beginning on September 1, 2012 and ending on January 31, 2013, and the denominator of which is 153. Coach shall reimburse Ohio State for any fees and/or expenses up to Ten Thousand Dollars ($10,000) relating to the establishment of the defined contribution plans in this Paragraph 3.2.

For the period beginning February 1, 2013 and for each subsequent “contract year” (February 1 through January 31), Ohio State shall pay Coach Eight Hundred Thousand Dollars ($800,000) (plus any additional amounts payable pursuant to Section 3.2(6)) in substantially equal monthly installments and in accordance with normal Ohio State procedures. In addition, for the period beginning February 1, 2013 and for each subsequent contract year, Ohio State shall contribute One Million Dollar ($1,000,000) per contract year to the DC Plan on January 31 of the applicable contract year (or in more frequent installments as determined by Ohio State in its sole and absolute discretion). Notwithstanding the foregoing: (a) to the extent that the Code limits or prohibits such contributions from being made to the DC Plan, Ohio State shall contribute such amounts to a defined contribution plan that is a nonqualified deferred compensation plan; and (b) if Coach is not employed as Head Football Coach on the last day of the applicable contract year, the aggregate contribution to the plans described in this Paragraph 3.2.(4) for that contract year shall be equal to One Million Dollars ($1,000,000), multiplied by a ratio, the numerator of which is the number of days Coach was employed as Head Football Coach that contract year, and the denominator of which is 365.

Subject to any Code limits, Ohio State shall make an annual contribution of Fifty Thousand Dollars ($50,000) to The Ohio State University 403(b) Retirement Plan, as amended from time to time (the “403(b) Plan”), on January 31, 2013 and January 31 of each subsequent contract year (or in more frequent installments as determined by Ohio State in its sole and absolute discretion). Notwithstanding the foregoing, if Coach is not employed as Head Football Coach on the last day of the applicable contract year, the aggregate contribution to the 403(b) Plan for that contract year shall be equal to Fifty Thousand Dollars ($50,000), multiplied by a ratio, the numerator of which is the number of days Coach was employed as Head Football Coach that contract year, and the denominator of which is 365; provided, however, that for the contract year ending January 31, 2013, the radio numerator shall be the number of days Coach was employed as Head Football Coach for the period beginning on September 1, 2012 and ending on January 31, 2013, and the denominator of which is 153.

DANTONIO – Michigan State University: 401(a) Plan. The University shall make an annual contribution (the “Contribution”) for Coach’s benefit to a defined contribution retirement plan that meets the requirements of Internal Revenue Code (“Code”) Section 401(a)(the “Qualified Plan”). The twelve (12) month plan year (“Plan Year’) of the Qualified Plan and the Qualified Plan’s Section 415 limitation year shall begin on January 1 and end on December 31. The amount of the Contribution each Plan Year shall be the maximum employer contribution for the Coach’s benefit to the Qualified Plan that is permitted by Code Section 415(c) for that Plan Year. Each such annual Contribution shall be deposited into the trust or custodial account relating to the Qualified Plan not later than the last day of the Plan Year to which that Contribution relates. This annual Contribution shall be made for each Plan Year to which that ends during the term of this Agreement.

STOOPS – University of Oklahoma: Additional Stay Benefit. If Coach remains employed at the University through January 1, 2011, University will contribute sufficient amounts so that an aggregate sum of Eight Hundred Thousand Dollars ($800,000) (“Stay Benefit”) will be accumulated as of such date in the existing or new tax-qualified or authorized employee retirement programs or plans (the “Plans”) established by the University for the benefit of Coach under IRC Sections 401(a), 403(b), 415(m) and 457(b) pursuant to paragraph IV.D of the previous Contract between the parties which had an effective date of January 1, 2007. Coach will be entitled to the Stay Benefit if Coach remains employed at the University as Head Football

Coach through January 1, 2011 subject to the following provisions: If Coach is no longer with the University on or prior to January 1, 2011, then Coach shall be entitled to a pro rata portion of the Stay Benefit (the “Pro Rata Portion”) based on Coach’s completed months of service with the University from January 1, 2009 through January 1, 2011 divided by 24 (number of months in the period from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2011). However, if Coach voluntarily terminates employment on or prior to January 1, 2011 and assumes another coaching position, then Coach shall forfeit all of his right to the Stay Benefit whether accrued or unaccrued. Notwithstanding the foregoing, if Coach voluntarily terminates due to David L. no longer serving as the University’s President, then Coach may voluntarily terminate employment as Head Football Coach and assume another coaching position without forfeiting his Pro Rata Portion of the Stay Benefit.

PAINTER – Purdue: Supplemental Retirement Contributions.

3.1 Supplemental Plans. Purdue will contribute the Supplemental Retirement

Contributions into, and in accordance with the provisions of, the supplemental Plans for the

benefit of the Coach.

3.2 Supplemental Retirement Contributions. The Supplemental Retirement

Contributions for Supplemental Plan year 2011/2012 will be $292,000.00. The Supplemental

Retirement Contributions for each subsequent Supplemental Plan Year during the term will be

$300,000.00, as such amount may be adjusted under Section 3.3 below.

3.3 Plan Expenses. To the extent permitted by law, all costs and expenses for the maintenance and operation of the Supplemental Plans shall be paid from the applicable Trusts. If any Supplemental Plan Year Purdue incurs (i) any cost or expense directly attributable to the maintenance or operation of the Supplemental Plans which are not permitted by applicable law to be paid from the Trusts, including but not limited to the costs or expense (a) of responding to any examination or inquiry by the IRS regarding the tax qualification of the Supplemental Plans or (b) that are normally paid by a plan sponsor rather than from plan assets, such as the costs of redrafting the Supplemental Plans to maintain their tax qualification, or (ii) any costs or expense which a trustee of one or more of the Trusts assesses upon Purdue because Trust assets are not at that time sufficient to cover the trustee’s expenses, Purdue, upon providing written notice to the Coach, may reduce the Supplemental Retirement Contributions for that Supplemental Plan Year by the amount of such costs or expenses reasonably incurred by Purdue, provided always that Purdue shall not have the right to the Supplemental Retirement Contributions on account of any costs that are attributable to or arise out of its failure to timely perform its duties and responsibilities as sponsor of the Supplemental Plans. Further, in no event will costs and expenses of maintaining and operating the Supplemental Plans directly attributable to participation by other eligible employees be borne directly or indirectly by the Coach.

9. ANNUITY

MARSHALL – Wichita State: If Mr. Marshall completes the 2011-2012 season, he will receive a one-time payment of Five Hundred Fifty Thousand and No/1.00 Dollars ($550,000.00); provided, however, that should Mr. Marshall not complete the 2011-2012 season because of circumstances for any reason, Mr. Marshall will receive a one-time payment of Four Hundred Twenty-Five Thousand and No/1.00 Dollars ($425,000.00).

Beginning on April 16, 2012, a new annuity will be initiated for the remaining term of the contract at One Hundred Twenty-Five Thousand and No/1.00 Dollars ($125,000.00) per year, said amount to vest as of the completion of each successive basketball season. The total vested amount of the annuity will be paid at the conclusion of every fourth season (“Payout Year”) that Mr. Marshall is employed by the ICAA, i.e., paid at the completion of the 2015-16 season, completion of the 2019-20 season etc.; provided, however, if Mr. Marshall were to leave the employment of the ICAA for any reason at any time other than a Payout Year, he shall receive the total vested amount at that time.

For example: If Mr. Marshall were to leave the employment of the ICAA after completion of the 2012-2013 season, he would receive a one-time payment of One Hundred Twenty-Five Thousand and No/1.00 Dollars ($125,000.00); If Mr. Marshall were to leave the employment of the ICAA after the completion of the 2013-2014 season, he would receive a onetime payment of Two Hundred Fifty Thousand and No/1.00 Dollars ($250,000.00); if Mr. Marshall were to leave the employment of the ICAA after completion of the 2014-2015 season, he would receive a one-time payment of Three Hundred Seventy-Five thousand and No/1.000 Dollars ($375,000.00); after completion of the 2015-2016 season, he would receive a one-time payment of Five hundred Thousand and No/1.00 dollars ($500,000.00). The payment cycle would then start over and continue for as long as Mr. Marshall is employed by ICAA.

10. EXPENSE ACCOUNT

MUSCHAMP – University of Florida: Coach shall be paid an expense account for personal expenses of Sixty-Eight Thousand Thirty-Eight and 64/100 ($68,038.64) for the First Contract Year. Thereafter, Coach shall be paid an annual expense account for personal expenses of Sixty-One Thousand Dollars ($61,000.00) for each Contract Year this Agreement is in effect (prorated for any Partial Contract Year using the proration process described in paragraph 4 for Partial Contract Years.

This personal expense payment shall be paid in installments at the same time as base salary net of applicable taxes and withholding.

TUBERVILLE – University of Cincinnati: University will provide Coach with an annual Business Entertainment Allowance and Coaches Working Meals budget of $10,000, the expenditure and reporting of which shall be subject to University rules.

PETERSEN – Boise State University: Coach shall have a “public relations” account of $7,000 per year to be used for reimbursement for meals and other acceptable and appropriate activities relating to the furtherance of the business of the University, and such funds shall be expended only in accordance with University and State Board of Education policies.

CRONIN – University of Cincinnati: Coach will have use of an expense account at a level determined by the Athletic Director annually, not to exceed Ten Thousand Dollars ($10,000) per year. All expenses must be accounted for with receipts and other information in accordance with Athletic Department policies.

BOWDEN – University of Akron: As additional supplemental compensation…the University shall: vi. reimburse Coach up to the amount of $12,000 annually, for non-traditional expenditures related to entertainment expenses associated with Coach’s development efforts, in accord with the then-current University policies. All expenses must be pre-approved by the Director, which approval shall not be unreasonably withheld, and Coach must provide an annual accounting of expenses to the Director and the Vice President for Public Affairs and Development.

SUMLIN – Texas A&M: Reimbursement for Spouse’s Official Activities. It is understood by the parties that from time to time Sumlin’s spouse may be called upon to travel to and/or attend various functions on behalf of the University, subject always to her reasonable availability. When engaged in such activities Sumlin’s spouse shall be entitled to payment for travel and other expenses incurred in such official activities. Spouse’s official activities may include, travel to all away football and bowl games, and special events at the invitation of the Director.

Reimbursement for Coach’s Official Activities. Sumlin shall be entitled to be reimbursed by University for customary expenditures incurred by Sumlin in the discharge of his duties under this Agreement afforded to employees of the University of commensurate rank and length of service, and of like term of appointment.

11. RELOCATION PAYMENT

TURGEON – University of Maryland: To facilitate the relocation and moving the Coach and his family from College Station, Texas, to Maryland, including costs related to the sale of the Coach’s current home, the purchase of a new home, and for temporary housing and moving expenses for the Coach and his family, the University agrees to pay the Coach Four Hundred and Fifty Thousand Dollars ($450,000), payable on or before June 1, 2011.

ALFORD – University of New Mexico (Terminated): Moving Expense Reimbursement. Moving expenses will be reimbursed as provided in University policy 4020, “Moving Expenses,” of the University Business Policy and Procedures Manual (UBPPM), up to a maximum of $15,000.00. If Coach Alford does not complete the first contract year from date of hire, he shall reimburse the University a prorated portion for moving and travel expenses paid by the University. In that event, the total amount paid shall be divided by twelve and the prorated amount to be reimbursed by Coach Alford shall be 1/12 times the number of months or partial months of the first contract year not completed. This provision shall apply whether Coach Alford resigns or is terminated by the University in accordance with this Agreement.

TUBERVILLE – University of Cincinnati: University will pay reasonable costs associated with Coach’s move to the Cincinnati area not to exceed $20,000 unless approved by UC in advance which approval shall not be unreasonably withheld, and provided Coach uses a University approved vendor and provides documentation of the costs.

University will pay reasonable costs for travel associated with Coach and his spouse’s efforts to locate a home in the Cincinnati area, not to exceed $5,000 unless approved by UC in advance which approval shall not be unreasonably withheld, subject to submission of appropriate documentation of such costs.

Coach will be provided a temporary housing allowance for a period of three (3) months in an amount not to exceed $6,000 per month unless approved by UC in advance which approval shall not be unreasonably withheld, payable in the pay period subsequent to submission of appropriate documentation of housing expenses.

MACINTYRE – University of Colorado: Moving Expenses.

i. The University will reimburse Macintyre allowable moving and lodging expenses up a maximum amount of Thirty Thousand Dollars ($30,000). Allowable moving expenses and lodging are as provided by University fiscal rules and University policy.

ii. For each Assistant Coach hired by Macintyre, the University will reimburse the Assistant Coach for allowable moving and lodging expenses up to a maximum amount of 10% of the Assistant Coach’s salary or Fifteen Thousand Dollars ($15,000), whichever is less. The Athletic Director’s prior written approval is required before any Assistant Coach is eligible for reimbursement under this subparagraph.

12. DISABILITY PAYMENT

SELF – University of Kansas: Termination in the Event of Head Coach’s Death or Disability. In the event of Head Coach’s death, his estate shall receive an after tax payment of $500,000 for every full year Head Coach has been employed as head men’s basketball coach after April 1, 2008. In the event of Head Coach’s disability, as defined below, Head Coach shall receive a payment of $500,000 for every full year Head Coach has been employed as head men’s basketball coach after April 1, 2008. A “full year” shall be defined as a year beginning on April 1 and ending on March 31. In the event of head Coach’s death or disability before the end of any such full year, this payment shall include an amount established by dividing by 365 a numerical figure obtained by multiplying the number of calendar days served during the partial year (that begins on April 1) by the amount of $500,000. This payment shall be made in the event Head Coach’s death or disability occurs at any time up to and including March 31, 2018 but in the event of head Coach’s death or disability between April 1, 2013 an March 31, 2018, this payment shall not include any amount for the days or years served prior to April 1, 2013. In addition, if Head Coach dies or becomes disabled before April 1, 2011, any amount paid to him under a prior Retention Agreement due to death or disability shall reduce the amount paid under this Agreement. Any payment under this provision shall be made thirty (30) days following the death or full disability of Head Coach. In the event Head Coach dies or is disabled after March 31, 2018, this provision is no longer effective.

Disability shall only be deemed to exist if Head Coach is:

a. unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that can be expected to result in death or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than twelve (12) months;

b. by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that can be expected to result in death or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than twelve (12) months, is receiving income replacement benefits for a period of not less than three (3) months under an accident and health plan covering employees of Athletics; or

c. determined to be totally disabled by the United States Social Security Administration.

PITINO – University of Louisville: In the event Employee becomes, in the opinion of a physician reasonably acceptable to Employer and Employee, so disabled as not to be capable of performing his duties hereunder for a period of six months or more, and said disability occurs during the period of the date of this Contract and March 31, 2013, Employee shall be entitled to receive the balance of the compensation which would have been due him pursuant to Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2 herein for a period of time commencing at the time of disability and ending at the earlier of termination of said disability or March 31, 2013, but for a period of no less than twelve months. Employer has purchased a long-term disability insurance policy from Lloyds of London on behalf of Employee under the terms of the Employment Contract between Employer and dated June 25, 2007, and Employer maintains the right to increase the amount of said coverage in order to reimburse a portion of the cost of disability benefits that may be paid by Employer to Employee until March 31, 2013. Subject to Employer’s ability to obtain an appropriate extension to Employee’s long-term disability insurance policy, in the event Employee becomes, in the opinion of a physician reasonably acceptable to Employer and Employee, so disabled as not be capable of performing his duties hereunder for a period of six months or more, and said disability occurs during the period of March 31, 2013 and June 30, 2017, it is the of Employer to pay Employee compensation pursuant to Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2 herein until the earlier of the termination of said disability or June 30, 2017. However, except as provided herein, Employer cannot assume the risk of self-insuring said payments to Employee. Therefore, Employer will use its best efforts to purchase long-term disability insurance on Employee from April 1, 2013 until June 30, 2017, for an amount equal to 100% of the employee’s compensation as defined in Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2. If such insurance is purchased and a disability benefits is paid from the policy due to Employee’s disability, Employee will be entitled to receive a disability benefit from Employer equal to the balance of the compensation due him pursuant to Sections 3.1.1 and 3.1.2 herein for a period of time commencing at the time of disability and ending when the disability insurance benefit is no longer payable, but no later than June 30, 2017. If, after using its best efforts to purchase longterm insurance, said insurance cannot be purchased, and Employee becomes, in the opinion of a physician reasonably acceptable to Employer and Employee, so disabled as not to be capable of performing his duties hereunder for a period of six months or more, Employer will assign to Employee and Employee shall have the right to designate the beneficiary for the death benefit payable under the life insurance policy owned by Employer as described in Section 3.1.14. The foregoing shall apply only if Employer is able to procure the life insurance policy described in Section 3.1.14. Thus, if Employer is unable to procure life insurance and long-term disability insurance for Employee, then Employer shall not be required to make any payments or assign any benefits to Employee pursuant to this Section 6.2 on account of Employee’s disability. Employee agrees to take all medical exams and to provide all medical history that may be required as a condition to obtaining said additional long-term disability insurance.

SPURRIER – University of South Carolina: Disability Insurance. During the term of this Employment Agreement, the University shall pay the premiums necessary to provide Coach with disability insurance income totaling Two Hundred Fifty Thousand Dollars ($250,000) annually until Coach reaches the age of 65.

CRONIN – University of Cincinnati: For each year that Coach is employed under the Term for which Coach elects coverage under one of the long term disability plans offered by the University, the University shall obtain a supplemental disability insurance policy in the name of Coach which will enable Coach to receive a total disability benefit from all sources equaling Twenty-Five Thousand dollars ($25,000) per month, starting with the first day he is declared totally disabled under the applicable University disability policy through the Term. As a of this undertaking, Coach agrees to fully cooperate in completing all requirements of the insurer in order to obtain coverage at the most advantageous rates and terms, including without limitation waiver of physician-patient privilege and rights of privacy under federal and state laws.

13. ENTREPRENEURIAL SHARING

HURLEY – University of Rhode Island: The Coach will also receive, in addition to his Base Salary, the sum of $175,000.00 (One Hundred Seventy-Five Thousand and no/100 Dollars) in each Contract Year as a guaranteed portion of the gate receipts for all home games administered by the URI Athletic Department. This amount shall be increased $15,000.00 (Fifteen Thousand and no/100 Dollars) in each Contract Year following the first Contract Year of the Term of this Agreement. Said amount shall be payable quarterly during the Term (on October 1, January 1, April 1 and July 1 of each Contract Year.) The first payment shall be payable on October 1, 2012).

FLECK – Western Michigan University: Football Game Attendance Incentive. In December of each year, University shall calculate the publicly announced home football game season attendance average using announced game attendance form the preceding, just completed, football season. University shall pay Employee one bonus if Employee meets certain game attendance standards in accordance with the following table:

If the publicly announced home football game season attendance average:

is 18,000 or higher, but is less than 20,000, Employee bonus shall be: $6,000

is 20,000 or higher, but is less than 25,000, Employee bonus shall be: $8,000

is 25,000 or higher, Employee bonus shall be: $15,00086

MOLNAR – University of Massachusetts Amherst: Gross Game Guarantees. Molnar shall receive, for each season during which Molnar serves as head football coach, ten percent (10%) of gross away game guarantees (“Away Game Payments”), up to a cumulative maximum of One Hundred Thousand Dollars ($100,000), provided, however, that said guarantees are based solely upon games scheduled at the authorization of the Athletic Director. Such Away Game Payments shall accrue, pro rata, with respect to each away game for which Molnar serves as head football coach relative to the total number of away games during that season, and shall be distributed on or before the last day of each Contract Year.

Ticket Incentive: For each season during which Molnar serves as head football coach, Molnar shall receive additional compensation as determined below (the “Ticket Incentive Payment”):

i. Twenty Thousand Dollars ($20,000) if the NCAA certified attendance at home football games averages Fifteen Thousand (15,000) during the regular season or

ii. Twenty-Five Thousand Dollars ($25,000) if the NCAA certified attendance at home football games averages Twenty Thousand (20,000) during the regular season or

iii. Thirty Thousand Dollars ($30,000) if the NCAA certified attendance at home football games averages Twenty-Five Thousand (25,000) during the regular season or

iv. Thirty-Five Thousand Dollars ($35,000) if the NCAA certified attendance at home football games averages Thirty Thousand (30,000) during the regular season

The Ticket Incentive Payment, if any for a Contract Year, shall accrue, pro rata, with respect to each home game for which Molnar serves as head football coach relative to the total number of home games during that season, and shall be distributed on or before the last day of the Contract Year.

DAVIS – Central Michigan University: For each home basketball game that is sold out during the Term, Coach will receive an additional lump sum payment of two thousand five hundred dollars ($2,500). Attendance will be calculated based on athletics department official ticket counts.

KINGSBURY – Texas Tech University: Attendance Achievement. If the average paid attendance at home football games equals or exceeds an average of 95% of Paid Seating Capacity during a Contract Year – $50,000. For purposes of this provision, Paid Seating Capacity for football is 60,454. Paid Seating Capacity is subject to change based upon future construction to Jones AT&T Stadium, and will automatically be adjusted for purposes of this provision upon completion of any such construction.

VII. PERFORMANCE BONUSES — PERQUISITES

In addition to the financial engineering, coaches also are handsomely paid for reaching certain plateaus with respect to performance of their jobs, as well as provided perquisites of a Chief Executive Officer. For instance, Tubby Smith, former University of Minnesota basketball coach, had a whole Exhibit (effective July 1, 2012) of incentive payments based upon a performance bonus plan.

In lieu of any other performance based bonus plan the University may adopt for sports coaches or other University employees, the University shall pay Coach the following incentive Bonuses, consistent with the requirements of all other terms of this Agreement:

I. NCAA Tournament. For each year the Team shall play in the NCAA Championship Tournament during the Term of Employment, the University shall pay Coach as follows:

a. Winning the National Championship, One Million Five Hundred Thousand and

No/100 Dollars ($1,500,000);

b. Playing in the National Championship Game, One Million and No/100 Dollars

($1,000,000);

c. Playing in the Final Four, Six Hundred Thousand and No/100 Dollars ($600,000);

d. Playing in the Elite Eight, Three Hundred Thousand and No/100 Dollars

($300,000);

e. Playing the Sweet Sixteen, Two Hundred Thousand and No/100 Dollars

($200,000);

f. Playing in the Second Round, One Hundred Fifty Thousand and No/100 Dollars

($150,000);

g. An invitation to play in the NCAA Championship Tournament, One Hundred

Thousand and No/100 Dollars ($100,000).

Coach shall receive the highest single bonus amount achieved under this schedule I.

Bonus amounts on this schedule I are not cumulative

II. Big Ten Finish. The University shall pay Coach a bonus based upon the Team’s Big Ten finish that concludes during each year of the Term of Employment, as follows:

Finish Amount of Bonus

a. Big Ten Regular Season Champion $250,000

b. Not lower than Big Ten Regular Season 2nd

place or tied for 2nd Place $150,000

c. Not lower than Big Ten Regular Season 3rd

Place or tied for 3rd Place $100,000

d. Not lower than Big Ten Regular Season 4th

Place or tied for 4th Place $ 50,000

e. Big Ten Tournament Champion $250,000

Bonus amounts on this schedule II are not cumulative except for the Big Ten Tournament Championship

III. Academic Performance. The University shall pay Coach a bonus based on the Annual Academic Progress Rate (“APR”) for the Team as established each year by the NCAA,beginning at the end of FY 2008, as follows:

a. APR greater than or equal to 930 $ 25,000

b. APR greater than or equal to 940 $ 50,000

c. APR greater than or equal to 950 $100,000

d. APR greater than or equal to 970 $150,000

Coach shall receive the highest single bonus amount achieved under bonus Schedule

III. Bonus amounts on this schedule III are not cumulative

IV. Graduation Rate. Each year, beginning at the end of the 2007-2008 academic year, the University shall pay Coach a bonus of One Hundred Thousand and No/100 Dollars ($100,000) if the four-year average of the Team’s six-year graduate rate, as determined by the University consistent with NCAA rules, is equal to or higher than 50%. The four year average shall be based on the rates of the just-completed academic year and the three previous academic years.

V. Coach of the Year Honors

a. Big Ten Coach of the Year $100,000

b. National Coach of the Year $100,000

Coach is eligible to receive either or both amounts under this schedule V.

VI. Annual Team Cumulative Grade Point Average (“GPA”).

a. Cumulative Team GPA of 2.9 or above $100,000

b. Cumulative Team GPA of 3.25 or above $150,000

Coach shall receive the highest single bonus amount achieved under this bonus schedule VI. Bonus amounts on this schedule VI are not cumulative.

VII. Contract Extension. The University agrees to extend the Employment Agreement and its Amendment for one year in the following circumstances:

a. Winning the Big Ten Regular Season Championship; or

b. Winning the Big Ten Tournament Championship; or

c. Playing in the NCAA Tournament Sweet Sixteen or better.

In each year, the contract extension shall be for a maximum of one additional year. Additional one year extensions may be earned in other years. The extension shall be from May 1 following the end of the existing Term of Employment through April 30 the following calendar year, and all other terms and conditions of the existing Employment Agreement shall apply to the extension period.

In addition to performance-based pay, coaches also demand and receive perquisites commensurate with the position. What follows is an example of the perquisites provided Matt Painter, Head Basketball Coach at the University of Purdue:

4.0 Additional Perquisites.

4.1 Purdue will sponsor the Coach’s membership in the Club, and will pay any initiation fees, monthly dues and assessments on the Coach’s behalf, in return for the public relations value to Purdue of the Coach’s presence at the Club’s various facilities and social contacts with its members and guests, at times of the Coach’s choosing, or as reasonably requested by Purdue from time to time.

4.2 Purdue will provide the Coach with a car allowance of $1,500.00 per month.

4.3 The Coach may conduct sports camps and retain the income therefrom in accordance with Purdue’s sports camps policies, as the same may be amended from time to time.

4.4 Purdue will provide the coach with one athletics department staff pass to the Birck Boilermaker Golf Complex.

4.5 Contingent on the present agreement between Purdue and NIKE, Inc. remaining in force without material amendment, the Coach may order (or, in the Coach’s discretion, the Coach’s assistant coaches and support staff may order), at no charge, up to a total of $25,000.00 (at Nike prices) per Fiscal Year of Nike merchandise from “Nike by Mail.”

4.6 Purdue shall provide to the Coach, free of charge, (i) eight season tickets to men’s basketball games for the Coach’s personal use, plus an additional twenty-five single game tickets for each men’s home basketball game for business use, (ii) season tickets for the Coach and each of his dependents for football games, (iii) two season tickets for women’s basketball games, (iv) two season tickets for volleyball games, (v) twenty tickets to each game in the Big Ten postseason tournament in which the Team is a participant, and (vi) twenty tickets to each game in the NCAA post-season tournament in which the Team is participant.

4.7 The Coach’s spouse and children may travel with the Team to away basketball games at Purdue’s expense under normal Purdue travel reimbursement policies as they may be changed from time to time.

VIII. MARQUEE SALARY CLAUSE

Nick Saban’s contract contains what is the equivalent of a marquee salary clause in a professional player’s contract wherein his compensation is always equivalent to the highest paid football coaches either in the SEC or the NCAA:

Market Rate Review. Commencing February 12, 2015 (and each February 1 thereafter through the end of the contract, as amended), the parties will meet for so long as necessary to determine the marketplace trends regarding head football coach compensation at Southeastern Conference (SEC) and National Collegiate Association, Division I, bowl subdivision (NCAA) institutions. Should the Employee’s “total guaranteed annual compensation” be less than that of the average of the “total guaranteed annual compensation” of the three highest paid SEC head football coaches; or less than that of the average of the “total guaranteed annual compensation” of the five highest paid NCAA head football coaches; then the University agrees to increase Employee’s “total guaranteed annual compensation” to the higher of the two averages, at said times. No more than one adjustment shall occur annually. For purposes of this paragraph, “total annual compensation” shall be defined as that terminology is generally understood and defined within the industry and may include base salary and talent fee and similar such payments as received by Employee and included in the calculation of Employee’s “total guaranteed annual compensation,” but shall not include bonuses or incentives earned, expense allowances, deferred compensation, longevity bonus payments, in-kind compensation, or other compensation of any nature not generally understood to be a part of a head collegiate football coach’s “total guaranteed annual compensation.” It is the intent of the parties, for purposes of this paragraph, to compare Employee’s “total guaranteed annual compensation” to similar amounts received by head football coaches at SEC and NCAA institutions. Therefore, the parties agree that, should