Compatibility of Adaptive Responses With Hybrid Simultaneous Resistance and Aerobic Training

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this investigation was to examine the effects of a hybrid, simultaneous, resistance and aerobic training program on aerobic power and muscular strength. Free-weight 1RM elbow flexor strength and cycle ergometer maximal aerobic power (CE VO2 max) were assessed for 15 untrained subjects. All tests were performed prior to and following a six-week training program. Subjects were randomly assigned to three training groups: an aerobic-training group, a strength-training group, and a simultaneous-training group. All training was performed three times per week. Aerobic training consisted of five to six, three-minute bouts of high-intensity exercise performed on a calibrated Monark cycle ergometer. All training intervals occurred at 85 to 100% of the subject’s CE VO2 max. Training intervals were separated by three minutes of rest. Strength training consisted of performing arm-flexion exercise with the subject’s dominant arm using a free-weight dumbbell. The strength training protocol consisted of performing four working sets of exercise per session separated by three minutes of rest. The first two weeks of training consisted of four sets of 10RM, the third week at 8RM, the fourth at 6RM, the fifth at 4RM, and the sixth at 2RM. The simultaneous training group performed both the aerobic and strength training protocols simultaneously. The aerobic and simultaneous groups significantly (p< 0.05) increased aerobic power 33.6 ± 6.1 to 39.1 ± 6.8 and 36.2 ± 3.7 to 42.3 ± 5.4 ml×kg-1×min-1 respectively. There was no significant difference in aerobic power increase between the aerobic and simultaneous training groups. The strength and simultaneous training groups significantly (p < 0.05) increased 1RM strength 11.36 ± 3.2 to 16.81 ± 5.1 kg and 13.81 ± 5.13 to 17.72 ± 6.15 kg respectively. There was no significant strength difference between the strength and simultaneous training groups. In conclusion, simultaneous high-intensity, cycle ergometer, aerobic training and one-arm, free-weight, strength training can be effectively utilized to increase maximal aerobic power and dynamic elbow-flexor strength. This study shows that the concept of simultaneous, high-intensity, aerobic and strength training is viable and that this approach to training may perhaps become a conditioning option for athletes and non-athletes.

INTRODUCTION

Strength and endurance training serve as the cornerstone of both athletic training and basic fitness regimens. A seemingly endless variety of modes, methods, and techniques are routinely utilized to achieve greater performance and fitness. At the forefront of these training methods is concurrent training. Concurrent training generally refers to the performance of both aerobic and anaerobic exercise within a fitness or athletic training program. To that end, strength and endurance training are applied in varying sequences within the same workout, daily, or weekly schedule. Athletes as well as popular and commercial fitness applications capitalize on these basic themes and supply the consumer with unlimited exercise options. Included within this variety are techniques which combine both resistance and aerobic training at the same moment in time, not separately. Such techniques are now very popular and are most commonly utilized in group-exercise settings in which individuals utilize barbells or dumbbells with the upper body and some kind of aerobic movement with the lower body at the same moment in time. For clarity, this type of training will be referred to as simultaneous training.

Currently, available research does not document simultaneous training as defined above. However, numerous studies have investigated the interactions of strength and aerobic training on muscular strength and aerobic power resulting from traditional same day or different day simultaneous training. These investigations often report mixed results (Abernethy & Quigley, 1993; Dudley & Djamil, (1985), Gravelle & Blessing, 2000; Hennessy & Watson, 1994; Hickson, 1980; Hunter, Demment, and Miller, 1987, McCarthy, Pozniak, and Agre, 2002; McCarthy, Agre, Graf, Pozniak, and Vailas, 1995). In all reviewed investigations, experimental training groups that performed concurrent training had no impairment in the magnitude of aerobic power increase as compared to those training groups that performed aerobic training only. The numerous physiological and structural adaptations resulting from aerobic training appear to be unaffected when combined concurrently with strength training. Some studies in which concurrent training was performed showed significantly less increase in muscular strength as compared to those experimental groups that performed strength training only (Dudley & Djamil, 1985; Hennessy & Watson, 1994; Hickson, 1980). Then again there are a number of studies which show little, if any, impairment in the magnitude of strength gain (Abernethy & Quigley, 1993; Hunter et al. 1987, McCarthy et al., 2002; McCarthy et al, 1995, Volpe, Walberg-Rankin, Webb-Rodman, and Sebolt, 1993). Most investigations reporting strength decrement report that strength gain decrement is isolated to the same muscle group that was utilized during the aerobic training portion of the study. Currently there is a lack of consensus among investigators as to the exact cause(s) of strength gain impairment as a result of concurrent training

Regardless of the degree of compatibility concurrent training may afford to increases in muscular strength and aerobic capacity, each of the aforementioned studies utilizes unique training methodologies and experimental designs. These key differences make it difficult to discern the degree of effectiveness and optimal application of concurrent training. Simultaneous training further complicates training and training outcomes due to its hybrid nature. This type of training is physically complicated and requires full body coordination. Since it does not involve a separation of the two modes of training and is relatively difficult to effectively coordinate, the efficacy of this training is unclear in either laboratory or group-exercise settings. The objective of this experiment was to examine the efficacy of synchronizing strength and endurance training and its effect on muscular strength and aerobic power.

METHODS

Subjects

Fifteen subjects, nine women and six men, ranging in age from 18 to 28, were recruited for this study (Table 1). Prior to data collection, subjects had not participated in a regular exercise program for a period of six months. All subjects were required to fill out a medical history questionnaire for the purpose of screening for contraindications to participation. The Southern Illinois University at Carbondale Human Subjects Committee granted approval for this study. Subjects were informed of the risks associated with participation in the study and subsequently signed an informed consent prior to data collection.

| Table 1. Subject characteristics (mean ±SD ) | ||

| Variable | Women (n = 9) | Men (n = 6) |

| Age (y) | 21.1 ± 2.6 | 21.2 ± 1.5 |

| Height (cm) | 158.5 ± 16.6 | 180 ± 6.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 69.8 ± 7.7 | 88.0 ± 20.7 |

| Body Fat (%) | 26.1 ± 5.2 | 15.2 ± 5.5 |

Experimental Design

Subjects were assigned to one of three training groups. Each training group was randomly assigned three women and two men. The first training group was a strength-training group (STG) only, the second was an aerobic-training group (ATG) only, and the third was a simultaneous-training group (SNTG). All subject testing occurred one week pre- and one week post-training. Subjects in all three training groups performed both strength and aerobic testing. All training was conducted three times per week at regular intervals, typically on an alternating daily basis. The duration of the training period was six weeks. All pre-testing took place within one week prior to and following the training period.

1RM Testing

A one repetition maximum (1RM) elbow flexion (bicep curl) test was performed unilaterally using the subject’s dominant arm. A plate loaded dumbbell was utilized for 1RM testing. Subjects were seated with their feet on the floor. Bicep curling was performed with the hand in the supinated position throughout the lift’s range of motion. A 1RM protocol consistent with NSCA guidelines was utilized prior to maximal testing (Baechle & Earle, 2000). A maximal lift was determined when the subject could complete only one repetition in strict form.

Aerobic Power Testing

A calibrated Monark cycle ergometer (Varberg, Sweden) was utilized for all aerobic power testing. Maximal cycle ergometer oxygen consumption (CE VO2max) was measured using a Parvo Medics, True Max 2400 Metabolic Measuring system (Concentius Technology). Subjects wore a Polar heart rate monitor during all testing. A five-minute submaximal warm-up period preceded commencement of the aerobic power testing protocol. A pedaling rate of 60 rpm was maintained throughout the test. An initial work load of 60 Watts (W) was performed for one minute. At the beginning of each minute following the first minute, pedaling intensity was increased by 30 W. Heart rate was annotated at the end of each respective workload. Cycle ergometer VO2max was determined by the occurrence of one of the following; a plateau or decrease in oxygen consumption with a subsequent increase in workload, obtaining age predicted maximum heart rate or volitional fatigue. A brief cool-down period followed test termination.

Strength Training

Strength training was performed unilaterally with the subject’s dominant arm. A plate-loaded dumbbell was used to perform elbow flexion (bicep curl) exercise. As with the 1RM trial, strength training was performed in the seated position. The first and third training sessions of each week were designated “heavy” training days while the second was a “light” training day. Pilot testing revealed that muscular and joint soreness were an issue with three heavy training sessions per week. A brief warm-up period, consisting of two to three sets of 12-15 repetitions at about 50% of the subject’s 1RM, preceded each training session. Four working sets were performed during each training session following the warm-up period. The strength-training protocol was periodized by RM loads over the course of the six-week training program. The first two weeks of training consisted of performing arm flexion exercise at the subject’s 10RM load. The third week was performed at the subject’s 8RM load. The fourth was performed at the 6RM load, the fifth at 4RM, and the sixth at 2RM. Training loads were adjusted as needed throughout training sessions to achieve target repetitions across all sets. Light-day training sessions were performed at approximately 75 to 80% of the heavy training loads. All working sets were separated by three minutes of rest.

Aerobic Training

Aerobic training was performed on a Monark (Varberg, Sweden) cycle ergometer. Cycles were calibrated each week. A heart-rate monitor was worn by each subject during training to monitor exercise intensity during training. Following a brief warm-up period consisting of five to 10 minutes of light, sub-maximal pedaling, aerobic training commenced. Training sessions consisted of five, three-minute exercise intervals separated by three minutes of rest. All training intervals were performed at a pedaling rate of 60 rpm. Exercise bouts were performed at power outputs corresponding to the subject’s 85 to 100% CE VO2 max. Beginning the fourth week of training a sixth training interval at 85 to 100% VO2 max was added. Percentages of the subject’s CE VO2 max were calculated using the Karvonen method (American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM], 2000).

Simultaneous Training

Simultaneous training consisted of both the strength and aerobic training protocols performed at the same time. Upon initiating the aerobic training protocol and achieving the desired pedaling rate of 60 rpm, subjects were handed an appropriately loaded dumbbell. Subjects continued pedaling while curling the dumbbell until the desired repetition number for that set was achieved. Coordination of simultaneous exercise activities was achieved quickly by each subject. Upon completion of the set the dumbbell was removed and the subject completed the aerobic interval.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using the SIUC mainframe Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS) program. Measures of central tendency and spread of data were represented as means and standard deviations. The experimental protocol employed a repeated measures design. A two by three repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyze within and between group differences. Between- and within-group analyses consisted of the following for each group: 1) pre- and post- training 1RM and 2) pre- and post-training aerobic power measurements. The criterion alpha level was set at p < 0.05. All statistically significant interactions were analyzed to determine if either of the training groups had greater increases in either aerobic power or muscular strength from pre- to post-training than other training groups. Differential effects, a post-hoc technique, were utilized to analyze significant interactions between training groups (Khanna, 1994).

RESULTS

Muscular Strength

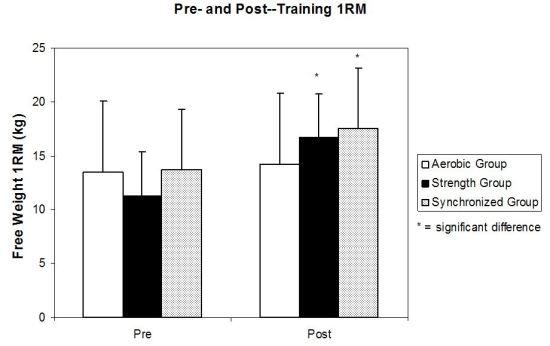

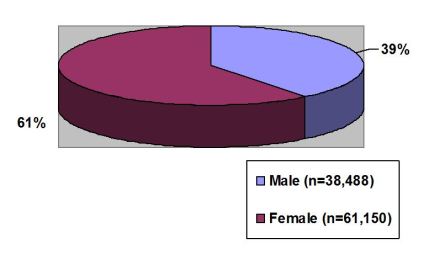

There was a significant increase in 1RM for the simultaneous training group from pre- to post-training (13.81 ± 5.13 to 17.72 ± 6.15 kg), an increase of 28.29%. There was a significant increase in 1RM for the strength training group from pre- to post-training (11.36 ± 3.20 to 16.81 ± 5.1 kg), an increase of 48.0% (Figure 1.). There was no significant difference in muscular strength increase between the simultaneous and strength training groups. The aerobic training group had no significant increases in muscular strength.

Figure 1. Changes in muscular strength pre-training to post-training.

Aerobic Power

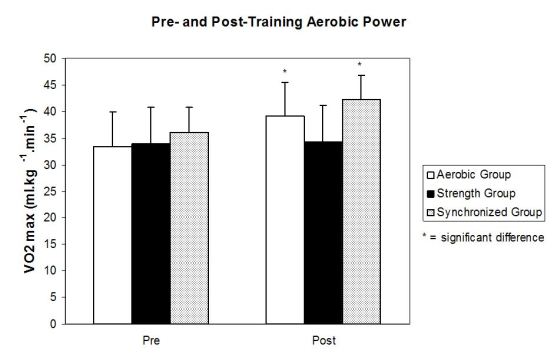

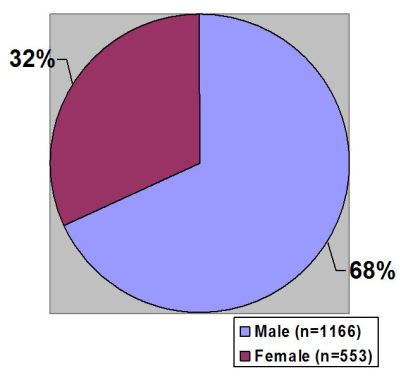

The simultaneous training group significantly increased CE VO2max from pre- to post-training (36.2 ± 3.7 to 42.3 ± 5.4 ml · kg -1 · min-1), an increase of 16.75%. The aerobic training group significantly increased CE VO2max from pre- to post-training (33.5 ± 6.1 to 39.1 ± 6.8 ml · kg -1 · min-1), an increase of 16.49% (see Figure 2.). There was no significant difference in the magnitude of increase of the CE VO2max between the aerobic and simultaneous training groups. There was no significant increase in aerobic power for the strength training group.

Figure 2. Changes in aerobic power, pre-training to post-training.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, simultaneous training induced significant increases in both aerobic power and muscular strength. The independent strength and endurance training programs produced significant increases in both muscular strength and aerobic power respectively. Results indicate that hybrid simultaneous training, consisting of strength training and high-intensity aerobic training is capable of inducing significant increases in both muscular strength and aerobic power.

In simultaneous exercise, especially in group settings, the upper body is most benefited by resistance training since the lower body is performing the primary aerobic movement. Therefore, the greatest muscular strengthening occurs in the musculature of the upper body. Kraemer et al. (1995) referred to this effect as compartmentalization in which the upper body muscle groups are essentially unaffected by any negative effects of aerobic training. Group simultaneous exercise typically involves the use of relatively light barbells, dumbbells, or power bands. Training sessions persist up to an hour and include a variety of aerobic and resistance training movements. In the current study, utilizing lighter weights and a variety of movements was not practical. A primary goal of this study was to explore the efficacy of applying the two types of training so that the respective aerobic and resistance training stimuli occurred at the same time as in group settings. Given the results of the current investigation, it is reasonable to presume that group-style simultaneous training is a viable form of training.

Changes in aerobic capacity represent a durable adaptation in concurrent training. Superficially, it appears as if many physiological and structural adaptations that occur as a result of performing aerobic and strength training exercise may be antagonistic to each other. The specific adaptations common to endurance training include increases in capillary density, myoglobin, mitochondria, and oxygen uptake (Holloszy & Coyle, 1984). Aerobic training also has a tendency to decrease myofibrillar protein production in the muscle (Hoppeler, 1986). Strength training, however limits mitochondria, capillary supply, and production of aerobic enzymes (Luthi, Howald, Claassen, Vock, and Hoppeler, 1986; MacDougall, Sale, Moroz, Elder, Sutton, and Howald, 1979). According to Hurley, Seals, and Eshani (1984) while peripheral changes are important in the development of aerobic power, adaptations of the central circulatory mechanisms such as cardiac output and stroke volume are not affected by strength training. With respect to aerobic and strength training independently, this demonstrates that some physiological and structural adaptations to exercise have a more profound effect on the magnitude of the increase or decrease than others. The lack of significant difference in VO2max increases between the endurance and concurrent groups in several studies demonstrate that the development of aerobic capacity is independent of muscular strength increase (Dudley and Djamil, 1985; Hickson, 1980, Hunter et al. 1987; McCarthy et al. 2002; McCarthy et al., 1995; Volpe et al., 1993). The aerobic results of the current study were in agreement with those of the concurrent training studies.

Resistance training in its various forms elicits increases in muscular hypertrophy, increased stores of ATP and PCr, force generation, and anaerobic enzymes (Costill, Coyle, Fink, Lesmes, and Witzmann, 1979; Fleck & Kraemer, 1988; MacDougall, Sale, Elder, and Sutton, 1982; MacDougall et al., 1979). However, the greatest issue surrounding any type of simultaneous training regimen is strength gain inhibition. In some concurrent investigations in which the lower body was involved in strength and aerobic training, the lower body strength gains in the concurrent training groups were inhibited (Dudley & Djamil, 1985; Hennessy & Watson, 1994; Hickson, 1980). In Leveritt and Abernethy’s (1999) investigation, the ability of subjects to perform strength training was reduced following aerobic training. The strength inhibition experienced in the lower body demonstrates the susceptibility of the legs in general to strength gain impairment in response to concurrent training. Studies that performed resistance training with the upper body noted few if any problems with upper body strength increase when the legs were used to perform aerobic training. Kraemer et al. (1995) reported that effects of upper body strength training performed with endurance training seem to be generally compartmentalized to the upper body musculature, and did not significantly affect the force production or endurance capabilities of the lower body musculature. Interestingly, this does not appear to be the same relationship with aerobic and strength training performed by the arms. Abernethy and Quigley’s investigation (1993) noted no strength gain inhibition in a concurrent group that performed arm ergometry and isokinetic arm strength training. It was noted that further research will be needed to understand the different strength adaptation patterns in the quadriceps and triceps brachii respectively. The current study is in agreement with concurrent training study observations that show the upper body strength increases are not compromised by the aerobic activity performed by the lower body. Sale, MacDougall, Jacobs, and Garner (1990) noted; whether impairment, compatibility, or synergistic enhancement occur, the application of training volume, intensity, frequency, mode, training status of subjects decides the final outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

In the current investigation, aerobic and strength gain adaptations resulting from simultaneous training group were not negatively impacted. The adaptations of hybrid simultaneous training are much aligned with observations of traditional simultaneous training. While simultaneously achieved, muscular strength and aerobic power adaptations in the present study were likely not achieved due to the respective adaptations functioning in a complimentary capacity, but perhaps a compatible or even independent capacity. This training technique does pose limitations with respect to equipment, coordination, and number of exercises possible in combination. However, this type of training appears to be effective and may be used as a legitimate, but limited mode of exercise or conditioning. This type of training may also be used for off-season and pre-season conditioning for athletes as well. In conclusion, in untrained adults, simultaneous strength and aerobic training are as effective for increasing muscular strength and aerobic power.

References

1. Abernethy, P.J. & Quigley, B.M. (1993). Concurrent strength and endurance training

of the elbow extensors. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 7, 234-240.

2. American College Of Sports Medicine (ACSM) (2000). ACSM’s Guidelines for

Exercise Testing and Prescription. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins.

3. Baechle, T.R. & Earle, R.W. (2000). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning.

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

4. Costill, D., Coyle, E., Fink, W., Lesmes, G. & Witzmann, F. (1979). Adaptations

in skeletal muscle following strength training. Journal of Applied Physiology, 46, 96-99.

5. Dudley, G.A., & Djamil, R. (1985). Incompatibility of endurance and strength training

modes of exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 59, 1446-1451.

6. Fleck, S., & Kraemer, W. (1968). Resistance training: physiological responses and

adaptations. Physician and Sportsmedicine, 16, 108-119.

7. Gravelle, B.L. & Blessing, D.L. (2000). Physiological adaptation in women

concurrently training for strength and endurance. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 14, 5-13.

8. Hennessy, L.C., & Watson, A.W. (1994). The interference effects of training for

strength and endurance simultaneously. Journal of Strength Conditioning and Research, 8, 12-19.

9. Hickson, R.C. (1980). Interference of strength development by simultaneously training

for strength and endurance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 45, 255-269.

10. Holloszy, J. & Coyle, E. (1984). Adaptations of skeletal muscle to endurance

exercise and their metabolic consequences. Journal of Applied Physiology, 56, 831-838.

11. Hoppeler, H. (1986). Exercise-induced ultrastructural changes in skeletal muscle.

International Journal of Sports Medicine, 7, 187-204.

12. Hunter, G., Demment, R., and Miller, D. (1987). Development of strength and

maximum oxygen uptake during simultaneous training for strength and endurance. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 27, 269-275.

13. Hurley, B.F., Seals, D.R., and Eshani, A.A. (1984). Effects of high intensity strength

training on cardiovascular function. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 16, 483-488.

14. Khanna, R. (1994). An analysis of the teaching, understanding and interpretation of

interaction effects in a factorial design. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale.

15. Kraemer, W.J., Patton, J.F., Gordon, S.E., Harman, E.A., Deschenes, M.R., Reynolds,

K., Newton, R.U., Triplett, N.T., and Dziados, J. (1995). Compatibility of high-

intensity strength and endurance training on hormonal and skeletal muscle adaptations. Journal of Applied Physiology, 78, 979-989.

16. Leveritt, M. & Abernethy, P.J. (1999). Acute effects of high-intensity endurance

exercise on subsequent resistance exercise activity. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 13, 47-51.

17. Luthi, J.M., Howald, H., Claassen, H., Rösler, P, Vock, P. & Hoppeler, H.

(1986). Structural changes in skeletal muscle tissue with heavy resistance exercise. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 7, 123-127.

18. Macdougall, J., Sale, D., Elder, G., & Sutton, J. (1982). Muscle ultrastructural

characteristics of elite powerlifters and bodybuilders. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 48, 117-126.

19. Macdougall, J.D., Sale, D.G., Moroz, J.R., Elder, G.C.B., Sutton, J.R. &

Howald, H. (1979). Mitochondrial volume density in human skeletal muscle following heavy resistance training. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 11, 164-166..

20. McCarthy, J.P., Pozniak, M.A. & Agre, J.C. (2002). Neuromuscular adaptations to

concurrent strength and endurance training. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 34, 511-519.

21. McCarthy, J.P., Agre, J.C., Graf, B.K., Pozniak, M.A., & Vailas, A.C. (1995).

Compatibility of adaptive responses with combining strength and endurance

training. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 27, 429-436.

22. Sale, D.G., Macdougall, J.D., Jacobs, I., & Garner, S. (1990). Interaction

between concurrent strength and endurance training. Journal of Applied

Physiology, 68, 260-270.

23. Volpe, S.L., Walberg-Rankin, J., Webb Rodman, K., & Sebolt, D.R. (1993).

The effect of endurance running on training adaptations in women participating in a weight lifting program. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 7, 101-107.