Submitted by: David Larimore, Ph.D & George Chitiyo, Ph.D

Abstract:

Intercollegiate athletics impact society in numerous positive ways. A number of studies have been done seeking to establish the effects of these sports programs on athletes, their institutions, and society at large. This paper is a synthesis of the literature concerning the non-economic impacts of sports. The findings largely support the notion that athletics are beneficial, not only to athletes, but to society in general. Many important lessons and virtues are derived from athletics. Among the many benefits to higher education institutions are the concepts of attracting more admissions applications and enhancing institutional name recognition and visibility.

Introduction:

Athletics provide entertainment, physical development, social interaction, and business (Cigliano, 2006). They create platforms for individual recognition and institutional visibility. There are many positive externalities associated with athletic activities. Attaching monetary value to these effects is difficult, as the value is based on societal satisfaction measures that are hard to measure.

Athletics Mould Virtues

Athletics help shape the social character of participants (Rudd and Stoll, 2004). A sample of 595 students from several universities was used in a causal-comparative study in which athletes and non athletes were compared concerning social and moral character. There were significant differences between athletes and non athletes. The main conclusion was that sport helps build character in terms of teamwork, loyalty, and self-sacrifice. There is no evidence to support the idea that athletics help build moral character, though neither is it proven that they do not do so.

Yiannakis, Douvis, and Murdy (2003) studied the perceived economic and non-economic impacts of sports. The findings are based on a survey of 702 residents and students of Connecticut attending two universities. They measured the perceived impacts of sports in terms of job creation, infrastructure, image promotion, economic impacts, environmental impacts, crime, and deviancy, among others. The authors conjectured that conflicts, issues, ideologies, pain, success, and tragedy are all blended in sports. People identify with these and are able to better handle the challenges of life as they see teams fighting on the field of play.

Athletes learn the principles of self discipline, teamwork, winning and losing, hard work, and self confidence. They have their self esteem boosted (National Federation of High Schools, 2003). One athletics director at a community college within the Tennessee Board of Regents (TBR) said, “Athletics fulfill major commitments of our mission statement to educate the whole person, to develop teamwork and leaders, and to contribute to the personal health and well-being of our students” (Cigliano, 2006, p45).

Yiannakis et al. (2003) established that the perceptions of people regarding the positive impacts of sport differed based on whether one was a fan or not. Non fans tend to regard sports as a nuisance that causes traffic jams and pollution. Enthusiasts savor the joy brought by the victories of their teams. A relationship may exist between the degree of interest and the extent to which sports are perceived to be beneficial.

Cigliano’s (2006) qualitative study was done at two community colleges in the TBR to examine the economic, institutional, and human impacts of athletic programs. The participants from each college included the president, the athletics director, two coaches, and four student-athletes. Coaches from the colleges said they viewed athletics as vehicles that help some students stay in school. The discipline and structure in athletic programs help motivate student-athletes to take advantage of educational opportunities. The coaches spoke of employing discipline, monitoring class and study hall attendance, and using encouragement to motivate student-athletes to achieve academic goals and become academically successful. Indirectly, the study addressed the apparent conflict of goals between academic interests and athletics. As long as there is a good relationship between the sports departments and academics, goal conflict exists only as an abstract concept.

Student-athletes participating in Cigliano’s (2006) study stated the following as virtues they received: recognition, patience, becoming better persons, self-discipline, maturity, motivation, teamwork, knowing people better, working hard, perseverance, working together, self-confidence, and leadership. The presidents, athletic directors, and coaches identified leadership development, a sense of civic responsibility, loyalty, punctuality, team work, cooperation, winning and losing with class and dignity, being competitive, developing individual strengths and skills, getting along with people, obedience, discipline, learning to make independent decisions, adjusting to being on their own, and maturity as virtues learned from athletics.

In the words of one athlete:

As much as we have to be physically in shape…we definitely also need an attitude which enhances our performance. This…(is)…an inner attitude of confidence in your ability, determination to see what you can do, and delight in what may be possible. The positive vibes that surround a person with an attitude like this can spread (Depew1 , 1999).

The NFHS (2003) reported that sport promotes citizenship and sportsmanship by instilling a sense of pride in community, teaching lessons of teamwork and self-discipline, and facilitating the physical and emotional development of participants.

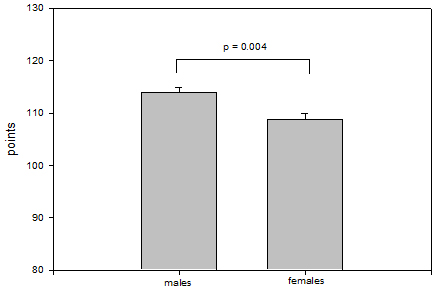

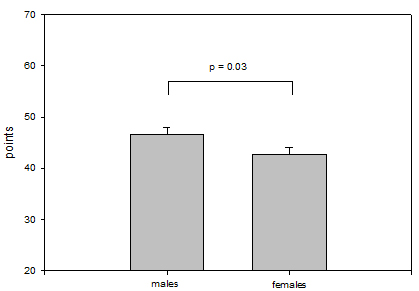

Bailey, Moulton, and Moulton (1999) compared athletes and non-athletes concerning levels of self-esteem and approval motivation. A sample of 492 university undergraduates participated in this study; ninety-four were athletes. The study used a multivariate analysis of variance to determine whether there was a significant difference between athletes and non-athletes on the variables of self-esteem and approval motivation. Athletes had significantly higher levels of self-esteem than non-athletes. There was also a statistically significant difference on approval motivation. Thus, athletes are “more likely to view themselves positively…and are less likely to engage in approval seeking behavior than non-athletes” (Bailey, Moulton, & Moulton, 1999).

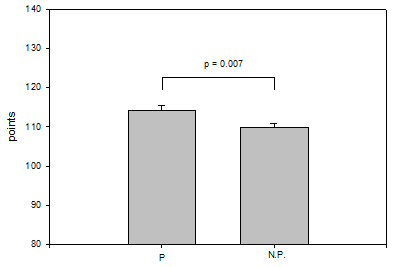

The ability of physical exercise to eliminate anxiety in university youth was investigated by Akandere and Tekin (2002). The sample was comprised of 311 students from Konya Selcuk University of Turkey who had never been involved in physical exercise. A sub-sample of sixty students who had the highest anxiety scores was split in half, so that thirty became the experimental group (which participated in organized physical activity) and the other thirty became the control group. Participation in physical exercise and physical activities decreased the anxiety level of both sexes.

Basking in Reflected Glory

Athletic activities relax the mind and “function as psychological and spiritual havens where disorder and moral ambiguities are resolved and managed through communal sport ritual practices and traditions” (Yiannakis et al., 2003, p.5). One of the perceived impacts lies in a concept called ‘Basking in Reflected Glory’ (BIRG). In Yiannakis et al.’s study, a majority of the respondents reported feeling ‘really good’ when their teams won and feeling ‘really bad’ when their teams lost. However, the relationship between sport-induced mood states, social identity, empowerment, and pro-social behavior is not fully understood and may require further inquiry.

One of the most popular studies on ‘BIRG’ was done by Cialdini et al. (1976)2. College students were found to be more likely to use the pronoun ‘we’ and to wear clothing that identified with their schools after a successful athletic weekend than during times when they had drawn or lost. Cialdini posited that people had a predisposition to associate with positive outcomes and make them their own. When one is ‘BIRG’, the person on the receiving end would not have done anything to bring the team’s success. Theirs is just to bask in unearned grandeur. When one’s team does well, it results in feelings of happiness, well-being, and collective euphoria. It has also been suggested that ‘BIRG’ improves mood in both individuals and communities.

On the flip side of the concept of ‘BIRG’ is ‘Cutting-Off Reflected Failure’ (CORF). The main ‘CORF’ strategy is to minimize the association between oneself and the losing team via several means, including by refusing to attend the teams’ matches’ and using terms such as ‘they’ rather than ‘we’. ‘CORF’ can be said to have somewhat positive results. The pessimism that precedes crucial matches can have the positive impact of uniting fans in the face of the possibility that it can all go wrong. Such an acceptance of a possible negative outcome can have the effect of protecting fans against disappointment as a result of failure. Having a shared moan can be a way of bonding3.

Reputation and Institutional Image

The reputation of an academic institution is closely tied to its sports programs (Cigliano, 2006; Pulsinelli et al, 1989). Thrilling performances by teams score points for the institution. High ranking sporting colleges are also ranked high in the academic arena.

The majority of respondents from Cigliano’s (2006) study mentioned a variety of values of publicity that athletic programs brought to the colleges, including a sense of excitement, activity, focus, free advertising, media coverage, service area communication, recruitment enhancement, and identity for local support to the institutions. The institutional image generated was said to be very positive. Good coverage amounted to free advertising. One of the presidents commented that:

Whether it is right or wrong, many people out in the community do not see anything in your college other than athletics. I mean, you have a certain constituent group out there that will even evaluate your college on how your athletic program is and people read about athletics in the paper. (Cigliano, p62).

In the study, athletic directors noted that visibility of their colleges was due more to athletics than any other department. They pointed out that institutional recognition is a function of the athletics program.

In a 2004 study, Frank mentioned the effect that spending on big time sports has on a university’s name recognition. Because these institutions are constantly making headlines in the public media, their names become more familiar to prospective students than those which are not publicized. This is likely to influence them in the college decision-making process. In such instances, “a big-time athletic program serves much like a national advertising campaign” (Frank, p15).

While athletes are students, they are also considered role models by their fans. People identify with role models on the sports field (Yiannakis et al., 2003). James Sheridan, a cross country athlete at Kenyon College, said, “athletes represent (their institutions) across the country and the type of attitude (they) project reflects on (the) entire learning institution” (Depew, 1999).

Enrollment

Athletics have a positive effect on enrollment. Pulsinelli, Borland, & Goff (1989) postulated that in order for sporting teams to be self financing, athletic teams would have to ‘attract’ a certain number of non-athletic students to the university. Enrollment data for the years 1960 to 1988 were analyzed with winning percentages for football and basketball. Overall, high sporting performance was associated with increased enrollment. This study alluded to the fact that recruiting high profile athletes might increase enrollment because of the indirect ‘attracting influence’ exerted on non-athlete aspiring students. When choosing among schools that offer athletic programs, non athletes prefer schools that have winning records to those that do not.

An impact study of Nichols State University (NSU) by Coats and Cox (2004), found that athletics have an effect on enrollment apart from the economic impact. Nicholls State’s athletic programs directly supported 239 student athletes. It was estimated that these student athletes drew an additional forty-three friends or relatives to NSU. Furthermore, of the 105 members of the marching band, approximately a third would have enrolled elsewhere were it not for the existence of the athletics program. Thus, the NSU athletics and associated programs were directly responsible for attracting 322 students to NSU. These students, in turn, supported approximately fourteen faculty positions.

Toma and Cross (1996) examined undergraduate admissions applications for institutions that won the NCAA Division I-A national football championship and those that won the NCAA men’s basketball tournament for the years 1979 through 1992. Increases were recorded in undergraduate admissions applications in years following a championship season. Fourteen out of sixteen schools that won or shared championships in football recorded increases in the number of applications. In basketball, ten out of thirteen schools recorded increases in applications following the NCAA Tournament championship.

Frank (2004) analyzed the effects of successful athletic programs on soliciting additional applications and donations by alumni and others. He postulated that universities continue to expand expenditures when they may fail to cover direct costs because the athletic programs may generate indirect benefits in other domains of sufficient value to make up the shortfall. The study stated that, “If students are indeed more likely to apply to an institution with a successful athletic program…such schools will be more selective than others on…the average SAT scores of entering freshmen.” McCormick and Tinsley (1987) validated this by asserting that freshmen entering a school would have an average SAT score about thirty-three points higher than it would if it did not have a big-time athletic program. They estimated a multiple regression in which the average SAT score was dependent on several variables, including whether the school had a thriving athletics program. Their data came from about 150 schools for the year 1971, sixty-three of which had big time athletic programs.

The opportunity to participate in athletics is a primary consideration for students (Cigliano, 2006). One community college president stated that the athletic program attracted between eighty to one-hundred students who would not be attending college if the athletic program were not available for them. Another said that sports had a significant impact on enrollment because of the influence athletes had in attracting girlfriends, friends, and peers.

Academic Performance

Student athletes in Colorado were shown to have ‘significantly higher’ grade-point averages than their non-sporting counterparts (NHFS, 2003). Those in Jefferson County high schools were also shown to have higher grade-point averages than their non-sporting peers. The latter school district has matched the academic success of its students with success on the playing field (NHFS, 2003).

Schildnecht (2002) quoted studies by the North Carolina High School Athletic Association, the Colorado Department of Education, and the American College testing services to show that students who participated in sports performed better academically. Student athletes were also found to be more likely to graduate than their non-athletic counterparts.

In one study, which goes against the idea of athletics having a positive relationship with graduation rates, Mangold, Bean, and Adams (2003) explored the impact that athletic programs have on institutional graduation rates. Data on graduation rates for ninety-seven universities competing in NCAA Division IA basketball and football were regressed on several predictors. The results of the study did not support the hypothesis that colleges with successful sports programs would have higher graduation rates for students in general. On smaller campuses, involvement in a successful sports program was suggested to conflict with academic goals. This study provides an example of the post hoc fallacy. There’s probably some third variable that explains this negative relationship.

Lucas and Lovaglia (2002) found that non athletic scholars anticipated higher benefits from academic success than athletes. Their study, for which the sample was 135 students (of which thirty-three were athletes), sought to measure the perceptions of student athletes and non athletes regarding cost, benefit, and motivation towards academic success. They reported that student athletes had a lower motivation to perform academically than non athletes. This does not, however, necessarily support the notion that athletes struggle academically as compared to non athletes, as the authors suggested.

A study was done by Meier, Robinson, Polinard, and Wrinkle (2000) to see if pursuit of athletic goals had a negative impact on academic interests of universities as reflected by scores on the SAT and ACT. The data for the analysis came from Texas school districts for the years 1997-1998. Athletic budgets were found to have no relationship with school attendance. However, the study concluded that athletic budgets had a significant negative relationship with academic performance, although the statistical significance of the variables is unknown. The study acknowledges that there are positive benefits at the individual level. Whatever these impacts may be, it is tempting to suggest that these individual benefits, across the district, could collectively override the negative results of athletics across academic institutions.

Donations

Having reviewed literature pertaining to alumni donations, Frank (2004) concluded that there is evidence that links athletic success to alumni giving. Rhoads and Gerking (2000) also analyzed the role of success in intercollegiate football and basketball in attracting donations to universities from alumni and other sources. Results from regression analysis of panel data from eighty-seven universities showed that, year to year, changes in athletic success had a positive impact on alumni giving. Other donors were not as responsive. Longstanding athletic traditions were shown to attract charitable donations.

Clotfelter cited participation in extracurricular activities and athletics as one of the factors that affected alumni giving (2001). The study utilized a data set of graduates from fourteen private institutions and sought to establish factors associated with alumni donations. The data covered cohorts of individuals who entered the institutions in the fall of 1951, 1976, and 1989. The findings showed that over half of all donations were given by only 1% of all alumni, most of whom contribute annually.

In a 2000 study of 2,822 Vanderbilt University graduates, Dugan, Mullin, and Siegfried investigated alumni giving behavior during the eight years following their graduation. A probit model and a regression were run on the data of givers and non givers. Participation in athletics was found to generate a stronger sense of attachment to the university through group membership, a factor which would have a positive effect on giving. In addition, former athletes receive solicitations from special clubs of former athletes apart from the usual appeal for alumni contributions. For that reason, they are expected to contribute more than other graduates. Students who were members of athletic teams responded more favorably to requests for donations after graduation.

A Chance to Continue in Sport and Education

The awarding of scholarships to athletes affords the chance to further academic interests (Schildnecht, 2002). Athletic directors in Cigliano’s (2006) study expressed that athletics, “provides education for a group of people who might not be able to have an education.” Dropping athletic programs from state universities and community colleges would have the undesirable effect of removing opportunities for many student-athletes to follow their career goals and obtain an education while pursuing future success in athletics. For most, this will be the peak time of their sporting careers. Few venture into professional sports after college.

Negative Effects

A few issues can be raised concerning the negative effects of participation in college sports. Athletics consume time. Often, the athlete has to cope with the stress of attending to sporting obligations while fulfilling academic requirements. They have to submit assignments at the same time as every other student. For those who are not on scholarship, their families have to bear the increased burden of giving them pocket money, since they cannot manage jobs to supplement their incomes.

Stieber (1991) mentions the presence of a black market for athletes. In this situation, a supply and demand for cheaters exists coordinated by national sports bodies. The student athlete is generally discriminated against. The market for athletes is not a free market. It is, in reality, a monopoly. The buying cartel “exploits by eliminating the bidding process among its membership” (Stieber, 1991, p446). The resulting wage is lower for the athlete than what would be obtained in an uncontrolled market. The authors of this paper believe that Stieber’s argument would only hold for the very top tier of institutions, which have major revenue streams associated with football and basketball. For the other non-football and basketball athletes in those institutions and for the athletes in the rest of higher education, a full or partial scholarship may be more than the free market would generate.

Colleges have difficulty recruiting students who are good athletes and academically talented. Cigliano (2006) mentioned an apparent lack of preparation for college work for some of the student-athletes. However, this applied for the rest of the student body as well. Thus, it is not specific to student athletes.

Yiannakis et al. (2003) stated that sports were perceived to increase pollution by 62% of the respondents. Also, crime, gambling, alcohol abuse, and other illegal activities were viewed as increasing by up to 45%. Vandalism, assaults, and drug abuse were also feared to be increasing. There is a need, however, to establish the extent to which particular sports programs have a negative impact on a particular environmental setting.

Conclusions:

Athletics are beneficial to student athletes, to universities, and to society at large. Research points almost incontrovertibly towards the advantages associated with intercollegiate sports. National bodies responsible for sports are generally pleased with the results that athletics yield and would not support plans to reduce support for sports. However, athletes have to work under stressful conditions because of tight schedules and the demanding nature of their work. In some cases, student athletes are exploited by unscrupulous individuals and sports organizations. Ultimately, though, the benefits of athletics outweigh the disadvantages, albeit they are difficult to quantify.

Footnotes:

1 Gelsey Lynn, a cross country runner, as quoted by Depew, R (1999).

2 As cited by Posten, M. (1998).

3 The Mental Health Foundation: Football and Mental Health (n.d)

References:

Akandere, M. and Tekin A. (2002). The effect of physical exercise on anxiety: The Sport Journal Volume 5, Number 2.

Athletic policy manual of Duke University (2003). Retrieved May 18, 2006 from

Click to access Athletic%20Policy%20Manual.pdf

Bailey, K., Moulton, M., & Moulton, P. (1999). Athletics as a predictor of

self-esteem and approval motivation: The Sport Journal Volume 2, Number 2.

Chapin (2002). Identifying the real costs and benefits of sports facilities. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Working Paper.

Cigliano, L. M. (2006). A perceptual study of the impact of athletic programs in selected community colleges in the State of Tennessee: PhD Dissertation, East Tennessee State University.

Clotfelter, C. T. (1999). Who are the alumni donors? Giving by two generations of alumni from selective colleges. Nonprofit Management and Leadership. Vol 12(2). Pages 119-138

Coats, R. M., and Cox, K. C., (April 14, 2004). Economic impact of NSU athletics Retrieved May 29, 2006 from http://www.slec.org/uploads/EconomicImpact.pdf

Depew, R. (1999). Kenyon athletes define “Role Models” in their own words. Vol. 1(2). Retrieved June 12, 2006 from http://www2.kenyon.edu/orgs/Ksai/features/features11992.htm#sheridan

Dugan, K. Mullin, C. H. & Siegfried J. J. (2000). Undergraduate financial aid and subsequent giving behavior: Williams Project on the Economics of Higher Education. Discussion Paper No. 57. Retrieved June 15, 2006 from

http://opus.zbw-kiel.de/volltexte/2005/3672/pdf/DP-57.pdf

The Mental Health Foundation: Football and mental health (n.d) Retrieved June 23, 2006 from http://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/page.cfm?pageurl=football.cfm

Frank, R. H. (2004). Challenging the myth: A review of the links among college athletic success, student quality, and donations: Prepared for the Knight Foundation Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics.

Gerking, S., & Rhoads, T. A. (2000). Educational contributions, academic quality, and athletic success. Contemporary Economic Policy, 18, 248-254.

Lucas, J. W. and Lovaglia, M. J. (2002). Athletes’ expectations for success in athletics compared to academic competition: The Sport Journal Volume 5, Number 2.

McCormick, R., & Tinsley, M. (1987). Athletics versus academics? Evidence from SAT scores: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 95: 1103-1116.

Mangold, William D. (2003). The impact of intercollegiate athletics on graduation rates among major NCAA Division I universities: Implications for college persistence theory and practice. The Journal of Higher Education Vol.74( 5), pp. 540-562. The Ohio State University Press.

Meier, K. J., Robinson, S., Polinard, J. L., & Wrinkle R. D. (2000). A question of priorities: Athletic budgets and academic performance. The Texas Educational Excellence Project.

National Federation of High Schools Association (NFHS), (2003). Survey resources: The case for high school activities. Retrieved September 3, 2005 from http://www.nfhs.org/scriptcontent/Va_custom/vimdisplays/contentpagedisplay.cfm?content_ID=163

Posten, M. (1998). Basking in glory and cutting off failure. Retrieved March 14, 2006 from http://www.units.muohio.edu/psybersite/fans/bc.shtml

Pulsinelli, R.W., Borland, M. V., & Goff, B. L., (1989). Western Kentucky University’s athletic program: Financial burden or boon? Department of Economics, Western Kentucky University.

Rudd, A. & Stoll, S. (2004). What type of character do athletes possess? An empirical examination of college athletes versus college non athletes with the RSBH Value Judgment Inventory: The Sport Journal Volume 7, Number 2.

Schildknecht, J. (2002). Benefits of interscholarstic athletics: schooling in American society. Retrieved September 23, 2005, from

http://filebox.vt.edu/users/jschildk/portfolio/documents/Benefits%20of%20Interscholastic%20Athletics.doc

Stieber, J. (1991). The behavior of the NCAA: a question of ethics. Journal of Business Ethics. Retrieved June 13, 2006 from http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?index=5&did=572547&SrchMode=1&sid=1&Fmt=6&VInst=PROD&VType=PQD&RQT=309&VName=PQD&TS=1130169395&clientId=28564

Toma, J. D. & Cross, M. (1996). Intercollegiate athletics and student college choice: understanding the impact of championship seasons on the quantity and quality of undergraduate applicants. ASHE Annual Meeting Paper. http://www.edrs.com

University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Institutional plan 2004 – 2009. Retrieved May 18, 2006 from http://www.provost.uncc.edu/planning/lrp/institutional.pdf

Yiannakis, A., Douvis, J., & Murdy, J. (2003). Perceived impacts of sport: measuring the impacts of sport: Methodological and policy considerations V6. 174.